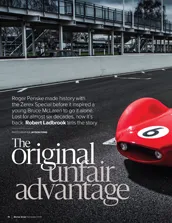

Zerex Special

The hype of the Goodwood Revival may centre on Ferrari 250s, Aston Martin DB4 GTs, rumbling Cobras and enduring E-types. But nestled in the entry for this year’s event is…

There’s a mystique about car badges – the trident on a Maserati nose, the simple B on a Mulsanne bootlid, even a tortoise, Gordon-Keeble’s nose-thumbing riposte to the athletic creatures of its rivals. We see the symbol, yet rarely think of the physical item – the casting and enamelling that carries the marque’s image. Yet these two-dimensional flag wavers must withstand rain and hail and sun and remain gleaming beacons of identity.

In the heart of Birmingham’s jewellery quarter, one manufacturer has made a name for itself by making names for others. Italian immigrant Antonio Fattorini began a retail business in Yorkshire in 1827 selling jewellery and watches which over the years expanded into manufacture of many sorts. Today it’s still a family firm – Greg Fattorini is the MD and Tom Fattorini handles exports – making civic regalia, trophies, ceremonial swords, jewellery and objets d’art – not to mention plastic badges by the ton at the Manchester plant. And should you get an OBE, the actual medal probably came from here. (They won’t sell you one, though – the Queen has sole distribution rights…)

But it’s those shiny labels your new car comes with that concern us, and Mark Arnold, industrial sales manager, gives us the run-through in his office within a handsome, listed Victorian building. On a shelf are dozens of car badges – TVR, Jensen, Noble, Ascari, McLaren, Atalanta. And Courage and Burton ale tap badges. “We do a lot of high-end whisky medallions too,” says Mark.

“We may be a craft industry, but we are not a cottage industry…”

“Almost all our automotive work is short-run or bespoke,” he continues. “We might be doing a batch of 25 Austin-Healey badges and then a run of Range Rover Autobiography Black fittings – we only do the high-end of Land Rover work, the limited editions. And we’ve just finished a run of Aston Martin Vantage badges for its spares department.”

It’s not just body badging: limited-edition vehicles may require dash, luggage and treadplates to receive that special little extra – for example, Holland & Holland badges are being readied to adorn the gunmaker’s special Range Rover edition. Mark also shows us examples of personal one-off jobs, such as named treadplates and a silver plaque to be affixed to a birthday present Rolls dashboard inscribed from a husband to his lucky wife.

“Every design has to be tested against salt spray and stone chips,” Mark says, “and now we have to use lead-free glass for EC end-of-life compliance, which is harder to work with. Some badges, such as on a Bentley airbag, are safety-critical too so they must be crash-tested with the car.”

I got to know the Jewellery Quarter while at art college in Birmingham, so as we cross the road to the building housing the big machinery I’m pleased to see the area still has its character, with bullion merchants, gemstone sellers and small manufacturies on all sides. You can buy a diamond here and take it next door to have a ring made. In Fattorini’s plant, though, things are on a bigger scale: at a towering stamping machine Jackie is dancing to her headphones as she stamps out the letters of ‘Range Rover’ while next door a 1000-ton press thumps ‘Land Rover 70th Anniversary’ into aluminium plaques for a limited-edition 4×4. Further on, fly presses chop off flash from the pressings before individual letters go through an annealing process on a fiery conveyor belt, rows of hot glowing ‘R’s picked off with tweezers into trays to cool. Now the raw emblems are chrome-plated (rhodium in the case of sterling silver, and occasionally gold) in the capacious plating room where Paul is hanging rows of Range Rover letters on ‘trees’ for dipping in the plating tanks.

We’ll come back to all this, though; now we see how a new badge begins, with an oversize pattern sculpted in clay, which is then scanned so that Phil can use Computer Aided Design to create a tool. On his screen he shows us the CAD model for the David Brown badge – the young British marque building the Speedback GT – spinning it around and zooming in to the immensely detailed level he needs to create the negative forming tool. This is fed to a CNC machine where digits turn into hard steel formers which Phil polishes with diamond paste before they’re ready for those big presses. Fattorini makes all its own dies, and behind are racks of tools labelled McLaren, Bentley, Rolls-Royce, Mini ready for the next batch. There’s also another huge stamp: boxing’s Lonsdale belt badges are made here, from sterling silver.

Back across the road again, to see how those deep rich colours are infused onto the badge casting. Mark introduces us to Pam, long-time enamel ‘laying in’ expert who makes a plain metal badge glow with colour. She’s one of five enamellers who handle the delicate work which doesn’t go through the roaring kiln. Vitreous enamel is of course coloured glass, and Pam shows us little trays of raw glass powder in pale blue and pinky-red, which turn to deep hues when she adds water. Picking up a David Brown emblem, she uses a steel stylus to smartly transfer the coloured paste into recesses on the badge and spreads it evenly. How does she know how much to apply? A shrug. “Been doing it for years.” They may have CAD and CNC capabilities across the road, but here it comes down to an expert eye and hand.

Now the dramatic part: laying a pair of badges on a grille, Pam picks up a gas torch (“the lamp”, she calls it) and plays the flame over them as casually as a painter with a brush. The badges glow and the glass liquifies until Pam is satisfied the coverage is even and puts them aside to cool. There are no other words for it; this is a black art – especially if the emblem is in silver and the operator has to stop just short of seeing the precious metal drip through the grille.

“It’s not easy to get new people into manufacturing today,” Mark says, “though we are training three enamellers. We’re trying to retain a critical mass of these skills within the Jewellery Quarter.”

Cooled and hardened, the badges go under a polishing wheel to remove the excess, the red, white and blue of the David Brown emblem emerging smooth and glossy, the lettering crisp and clear. Ridges in the metal base show through the blue glass as highlights; fancier milling and engine-turning can give almost jewellery qualities to the end result. Now whenever I see an ‘RR’ badge or Bentley ‘B’ I’ll have a picture in my head of Pam and her lamp.

Mark is proud of his firm’s work: “We have a strong craft heritage, but we also need to be fully up to speed with current CAD, machining and other engineering techniques. As I always say to visitors, we may be a craft industry, but we are not a cottage industry.”

It’s true. And now I know where to go when I need a new ceremonial mace.

Name Thomas Fattorini Ltd

Specialisation Enamel badges

Established 1827

Number of employees 70

Premises Birmingham & Manchester

www.fattorini.co.uk