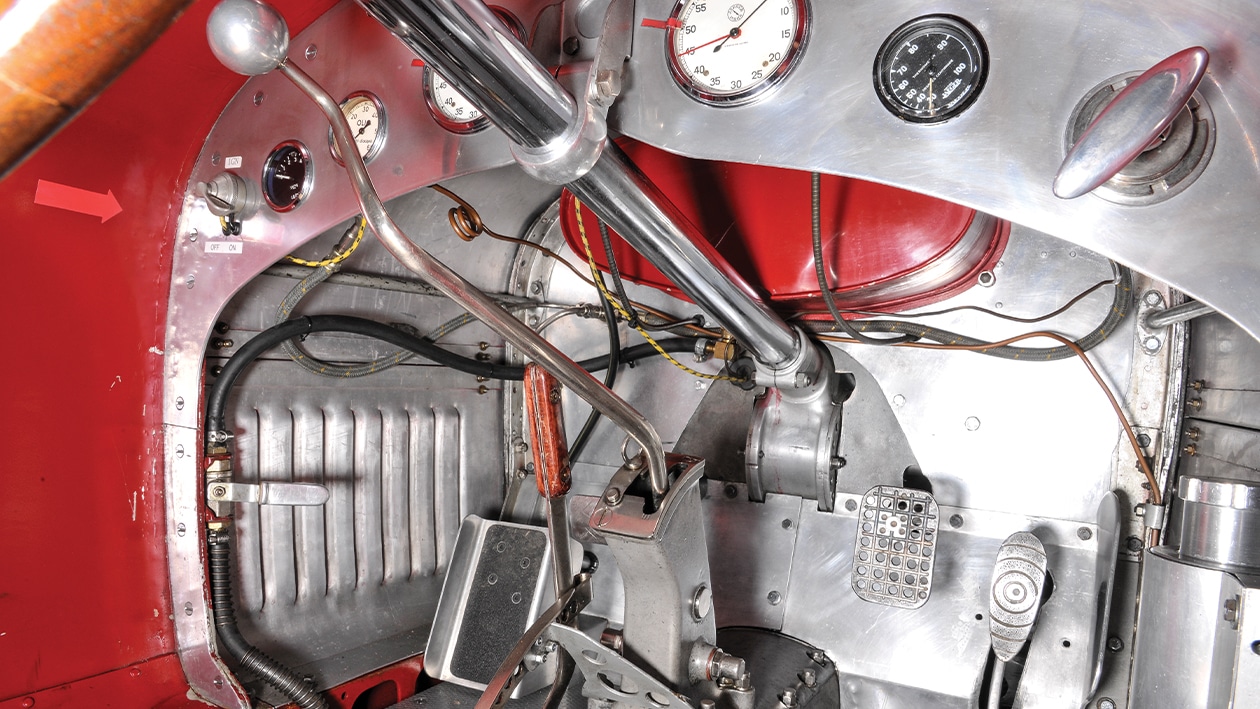

Driving it properly for the first time is a frankly bewildering experience. Other pre-war race cars I’ve driven – Astons, Bentleys, MGs – have been instantly understandable, accommodating and fun. I remember a Type 35 Bugatti that just egged me ever onwards from the moment I climbed on board. But I’m not really getting the hang of the P3. It should be easy because the engine has so much torque gear-changing is almost optional. What’s more the brakes are reassuring and even the gearlever finds its way around the gate simply enough once I’ve learned it needs a big blip between down-changes to account for those wide ratios. But it doesn’t gel. I do lap after lap and it’s not getting any easier. And then, as if in total disdain for the idiot behind the wheel, the Alfa stops dead again.

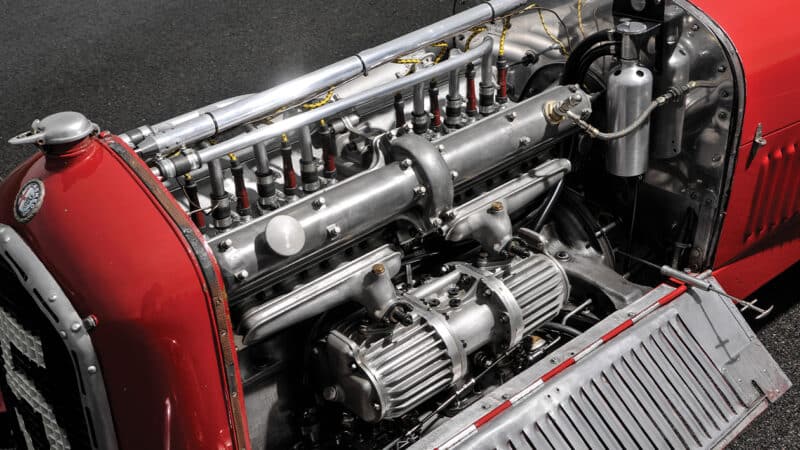

This time a quick glance at the fuel pressure gauge reveals it’s simply out of methanol. Hard to believe though it is, the P3 burns nearly a gallon of the stuff on every lap, and it’s little more than 1.5 miles round. The tank is refuelled and I set off again, determined to find where I’ve been going wrong with this car. The answer is not far away.

Mindful of the car’s value – which will be determined soon during a Paris auction but definitely stretches into the many millions – old tyres and the damp surface to which they’ve been trying to cling, I’ve been cautious. Too cautious as it happens. And as I’ve noted with other purpose-built racers in the past, a little courage can go a very long way.

This Tipo B might feature the ‘wide’ body mandated by 1934 regulations, but its natural elegance and poise are undiminished

Stuart Collins

Just raising the corner speed a touch puts some heat into the tyres, loads the suspension and starts the chassis and steering talking to you. Confidence builds. More revs reveal preposterous power for a pre-war car. When it was over I got back into a BMW i8, a quick car by the most modern of standards, and it felt broken by comparison. But it is the torque that beggars belief: even in top, which will be geared for something like 170mph, it just throws you up the road.

The suspension is still quite bouncy even with the independent front end, but it soon becomes clear how it should be driven. Never worry about missing the apex because the nose will always find it – the P3 doesn’t understeer at all. So your only concern is the back, which actually responds in quite a cultured way: it doesn’t snap, there’s plenty of traction and, sitting almost on top of the rear axle as you are, you know that if you’re roughly where you want to be the rear end will be there too.

So despite all the power, torque and absence of understeer, the P3 is not actually a car that naturally wants to be driven at hooligan angles of attack. It’s far more sophisticated than that, far more the precision instrument, at least by the standards of over 80 years ago.

It took time to get the Alfa started — with help from a towrope — but has any wait ever been so worthwhile?

Stuart Collins

I’m not sure why that should surprise me. This was after all not just a Grand Prix machine, but the fastest and most advanced the world had seen at that time. Until Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union came along with enormous engines and bottomless budgets, nothing could get near it.

And to me at least, the Tipo B will always have something those brutally impressive German monsters never had: a simple beauty born of perfect proportion and exquisite detailing. Which is why, when I think of the archetypal pre-war Grand Prix car, it is always a Tipo B P3 that appears in my head.

The Alfa Romeo Tipo B will be the star attraction at RM Sotherby’s auction at the Paris Rétromobile in February. It is expected to fetch in excess of £5m.

Milestone

How 1920s thinking survives on bikes that are ridden today

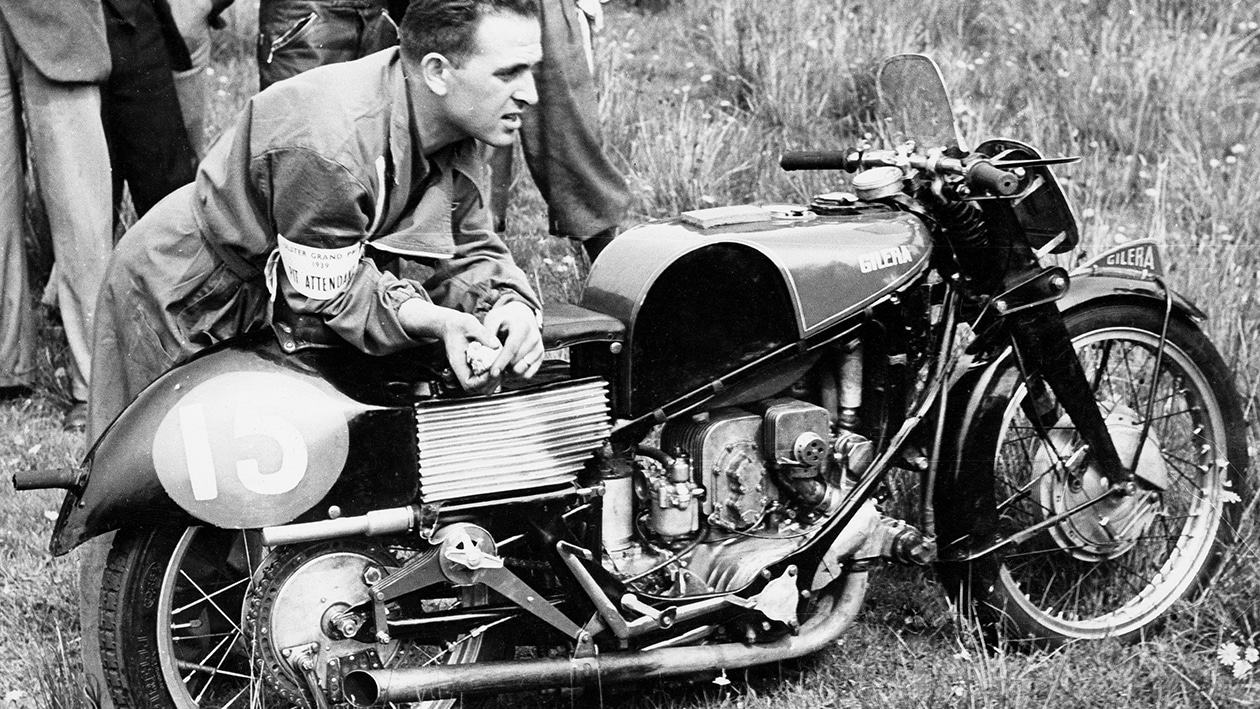

Thirteen years before Alfa Romeo revealed the game-changing P3, fellow Italian manufacturer Gilera presented the Rondine – a motorcycle that like the Alfa continues to influence to this day. The Rondine wasn’t the first four-cylinder bike engine, but it was the four that changed motorcycling. The top-of-the-range superbikes sold by BMW, Honda, Kawasaki, MV Agusta, Suzuki and Yamaha today use the same transverse-four engine layout pioneered by Gilera in the 1920s.

Conceived in 1923 by engineers Piero Remor and Carlo Gianini to offer a silky-smooth alternative to the jack-hammer singles that ruled the market, the engine was sold from one company to another, the industry apparently ignorant of its possibilities. In 1933 two racing aristocrats – Count Bonmartini and Prince Lancellotti – bought the engine and had it redesigned and supercharged in Bonmartini’s Compagnia Nazionale Aeronautica aircraft factory outside Rome. Bonmartini named his motorcycle Rondine, in honour of the CNA plane that had accompanied Mussolini during his march on Rome in 1922.

However, Bonmartini soon grew tired of this sideshow project and the Rondine changed hands yet again. This time motorcycle manufacturer Giuseppe Gilera bought the project, renamed the bikes and put them to work. In 1937 the Gilera Rondine raised the motorcycle speed record to 170.37mph, ridden by brilliant racer/engineer Piero Taruffi. Two years later it won the 500cc European GP series, defeating BMW’s supercharged boxer twin and a host of Norton singles.

Supercharging was banned in the wake of WW2, so the Rondine engine was redesigned by Remor. The new machine won five of the first seven 500cc world championships, even though the horsepower of the immediate post-war bikes overwhelmed their handling.

That changed in 1953 when Gilera poached Geoff Duke from Norton, where the Lancashire rider had learned how to make motorcycles go around corners. With the bike modified, Duke scored a hat-trick of 500cc titles. Today, the Gilera’s engine layout is recognisable in Valentino Rossi’s Yamaha M1 MotoGP bike: forward-inclined cylinders, central gear cam drive and so on. Mat Oxley