Lunch with... Jan Lammers

The Dutchman’s single-seater career petered out in the wake of much early promise, but he went on to enjoy great success in other spheres

James Mitchell

Whoever coined the expression ‘Nice guys don’t finish first’ might have been thinking of Jan Lammers. Here’s someone who was already displaying astonishing car control as a schoolboy, and who won his first touring car championship when he was 16. Someone who started his first Formula Ford race from pole, then won the European Formula 3 Championship and – just like the following year’s winner, Alain Prost – moved from there straight into Formula 1. Someone who, according to pundits on the look-out for emerging talent, was heading for the top, and who was tipped by Autosport to be “a world champion of the eighties”.

Yet that never happened. His brief time in F1 was frustrating and fruitless, apart from one potentially career-changing weekend that came to a shuddering halt 200 metres after the green light. Two seasons in Indycar were little better. But then this nice guy went on to become a brilliant endurance racer, scoring Jaguar’s first Le Mans victory for 31 years, and was a winner from Daytona to Brno, Del Mar to Mount Fuji. After five seasons with Jaguar he went on to race more different sports cars, with more top-level team-mates, than maybe anyone else in a career that has lasted more than 30 years, and hasn’t quite finished yet.

In 1956 Jan Lammers was born, fatefully, in the little seaside town of Zandvoort. His parents had no connection with motor sport, but their house just happened to be close by Holland’s only major racing circuit. Now, after roaming the world during his racing life and basing himself in California, England and Japan, he has returned to live in the town of his birth. For our lunch he chooses Café Neuf, a period restaurant which echoes the former Dutch colonies by serving us Indonesian chicken on a skewer, with peanut and spices. Zandvoort looks like any slumbering holiday resort in December, pummelled by winds off the sea and occasional squalls of rain. Jan, a small, slight figure, looks almost as youthful as he did when he was in Formula 1 35 years ago. He speaks perfect idiomatic English. Before we sit down to lunch we take a look at the circuit that has played such a part in his life. The layout is much changed, of course. In a sober moment we drive along part of the old track, little more than a footpath now, where in 1970 Piers Courage, and in 1973 Roger Williamson, died in flames.

Season-long battle brought Lammers the 1978 European F3 title

Tim Tyler

More cheerfully we look at the site of the old Rob Slotemaker skid pan. As a 12-year-old Jan would hang around watching the school fleet of Simca saloons slither around in the hands of usually incompetent pupils. The surface was coated with old oil and then hosed with water, and the cars soon became filthy. So he offered his services as unpaid car-washer, which involved driving each car across the pan to where the hose was. Jan, always small for his age, struggled to see over the wheel and reach the pedals, but when Rob’s back was turned he would put in lap after lap of the pan. Before long this little schoolboy had taught himself how to hold a full-power opposite-lock slide, and he moved from there into the car park and developed the ability to do 360-degree spins on dry Tarmac without stopping. Local people got to hear about him, and when he was 15 he was asked to cut the tape at the grand opening of a local supermarket, which he did sideways and backwards in one of the Simcas.

“When I was 16 I applied for a race licence, even though I was too young to drive on the road. Rob Slotemaker had been helping a young Dutch guy with his racing, Wim Loos, until Wim was killed at Spa. Now Rob wanted to help me, and he got me a Simca Rallye 2. I won my first race in that car and went on to win the Dutch Touring Car Championship. I also did touring car races in Germany with Rob: he ran a Camaro in the big class, I ran an Opel in the small class.” Slotemaker was killed in the Camaro at Zandvoort in 1979.

“Of course I wanted to get into single-seaters, and I met this guy Jan Bik. He had a brothel in Amsterdam, and was making very good money. He got me an old Formula Ford Crosslé, paid for everything. He showed me around his premises, but I never made any use of the facilities. The girls were rather intrigued: they were used to men bringing money in, but I was taking money out.

“One day I was working in the skid school as usual, and there was some sort of Formula Ford test laid on by Hawke and Crosslé. All the top Dutch guys were there, plus some hotshoes over from England. I asked the guy from Hawke if I could have a go. The other drivers were all very professional, immaculate overalls, the latest helmets. I was wearing jeans and an oily sweater, and I borrowed a cheap helmet from a moped rider who came to watch.

Fun Procars were some compensation for difficult 1980 with ATS

Motorsport Images

“I got into the Hawke, and somebody found a jacket to roll up behind my back so I could reach the pedals. I closed the visor and realised the moped man had never cleaned it, because it was almost opaque. I did three flying laps, came in, said ‘Thank you very much, nice car. I must get back to work now’. But they told me I’d been faster than anyone else, and I should try the Crosslé. After a couple of flying laps, as I came out of Bos Uit, I noticed the water temperature was way too high. I had been well brought up by Rob, I knew you must always respond to your gauges, so I switched off and coasted over the finish line with a dead engine. They said I was still quickest by 0.8sec.”

Out of that came a good deal for Jan Bik to buy a new Hawke for Jan, and he went further afield into Denmark and Germany. In 1977 Hawke gave him some drives in a works Formula 3 car. “It was a fun time – Warwick, Piquet, de Angelis, Johansson were all in F3 then – but the car wasn’t very competitive: a Ralt or a Chevron was the thing to have. By now an Amsterdam real estate broker was sponsoring me, and I told him if I had a decent car I could win the European F3 Championship.

“He wasn’t convinced, so I suggested we hire a Ralt and spend a day at Zandvoort. If I didn’t get under the F3 lap record he wouldn’t have to buy me one. Roger Heavens rented us a car, I did 100 laps and I think about 70 of them were under the record. So I got my Ralt, and in the 1978 European Championship I had a great battle all season with Anders Olofsson. We ended up on the same points, and both on the same number of wins. But I had one more second place, so I was champion.

“And then right away I got a Formula 1 offer, from Shadow. Of course I took it. I know, looking back, I was too eager: I was ready to handle Formula 1, that was no problem, but I should have stacked up more results, and maybe got an offer from a better team later. I had a Dutch tobacco sponsor, Samson, and I brought their money to the team. Shadow was not in a good way then: the Arrows breakaway had happened, so Jack Oliver, Alan Rees and, most important, Tony Southgate were all gone. Don Nichols was the team owner, and team manager was Jo Ramirez, who is probably the nicest man I ever met in motor racing. But the Shadow DN9 was not a good car.

“My team-mate was Elio de Angelis. It was his first F1 season too, but – maybe because of his karting background – I think he matured more quickly than me, he probably had the edge. He out-qualified me eight times, I out-qualified him five times. We both had a lot of retirements and my best finish was only ninth in Canada, but I did go well at Long Beach. I pulled that lorry around the streets to qualify 14th. In the race I got caught up in a first-corner pile-up and had a long stop to replace the rear wing, but when I got going again, running at the back, I set eighth-fastest race lap. Then at Monza my official qualifying time was 1min 39.088sec, Elio’s was 1min 39.149sec. Somehow he got on the back row of the grid, and I was posted as a non-qualifier. Well, he was an Italian, and we were in Italy – you work it out.

“For 1980 I went to ATS and Günter Schmid. Günter had the reputation of being a bad guy, but I don’t think he was the animal that people made out. I’m easy-going and laid-back, and I’ve always been pretty good at working with difficult people. Rob Slotemaker was wonderful to me, and he wasn’t the easiest guy. Tom Walkinshaw, of course; a lot of people found Tom very hard to take, but I got on really well with him. At ATS Gustav Brunner had just arrived, a very clever guy, and Roy Topp was chief mechanic. Roy looked after Jackie Stewart at Tyrrell, and he was one of the best mechanics I ever worked with. For a little team it was good.

Ninth in Montreal was his 1979 season high in difficult Shadow

Motorsport Images

“Then Samson pulled out, and I had no backing. ATS was a two-car team, Marc Surer and me, but they didn’t really have the funds to run a second car. At the first two races, Argentina and Brazil, my car was just all the team’s spares stuck together, and I was well off the pace and didn’t qualify. Günter decided to run only the new car for Marc Surer at Kyalami, so I was there as a spectator, and in first practice right in front of me Marc had a big accident, leaving him with a smashed ankle. The old car was there as a spare and Günter told me to get kitted up quick and go out in the last session. Because it was hotter everyone was slower, and I just failed to qualify.

“Then, with Marc still laid up, I was back in for the next race, at Long Beach – and I qualified fourth. That gave the whole team a huge boost. But my race lasted 200 metres. As I accelerated out of the first corner a driveshaft broke. That could have been a podium at least.

“By June Marc’s ankle had mended, I still hadn’t found any money, he was back in and I was out. I got a ride in Mo Nunn’s Ensign, but that was pretty hopeless.” Nevertheless, Jan was able to enjoy himself in the Procar series for identical BMW M1s, run usually as a support race for Grands Prix and with some top F1 faces in the line-up such as Jones, Piquet, Reutemann and Stuck. On a level playing field for once Jan was in his element, showing what he could do among exalted company in the big 3.5-litre mid-engined coupés. At the opening round at Donington he took pole, and won the race by 12sec. Three weeks later, at Monaco, he took pole again. “I led from the start, and it was looking good when Didier Pironi rammed me at Mirabeau and destroyed the back end.

“The M1 was a great machine. At the next round, Norisring, I led from the start again. I’d taped up all the cockpit vents to get more speed in a straight line, but that made it so hot that the fire extinguisher went off. An extinguisher puts out a fire by depriving it of oxygen, so it deprived me of oxygen. I passed out for a second or two before I realised what had happened. Then I got the window open and I recovered. By now I’d dropped to sixth place, but I managed to get back up to second before the end.

“In F1 I was back with ATS for 1981, but I hadn’t been able to raise any sponsorship, and after four races I was out of there. For 1982 I got a ride with Theodore.” Once again Jan had found himself in very much a lesser team. He only qualified the uncompetitive car once, for his home Grand Prix at Zandvoort, when he worked up from the back of the grid to 13th before the engine went.

That wasn’t quite the end of his rocky F1 career. A whole decade after his final outing for Theodore, he reappeared for the last two Grands Prix of the 1992 season. “It was March’s final days. A Dutch friend of mine, Henny Vollenberg, was involved there, and he was kind of the last man standing because everyone else had left. He got me into Karl Wendlinger’s March-Ilmor for the Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka. I played myself in on Friday, intending to go for it on Saturday. Then it rained so I couldn’t improve, but in the wet I was sixth fastest. In the race the gearbox packed up. Then we went to Australia and I did keep going until the end, although the gearbox was playing up again.”

Shoestring ATS budget meant that Jan’s car could rarely compete in tough 1980 campaign

Motorsport Images

Back to 1983: with no F1 in the offing, Jan was hired by Richard Lloyd to race the Canon-sponsored Porsche 956. “I drove for Richard for two and a half seasons, with Tiff Needell, Thierry Boutsen and then Jonathan Palmer. We had a lot of good placings, and Jonathan and I won the Brand Hatch 1000Kms in 1984. But during 1985, when we were preparing to go to Le Mans – we were eighth there in ’84 – I just felt less comfortable. I didn’t feel so happy with the team, I didn’t feel respected enough, and I believe you should never go to a race like Le Mans with mixed feelings.

“So I switched my attention to Indycar. I had a couple of races for Sherman Armstrong in a not very competitive March, and then I got friendly with this wonderful big, brash, loud-mouthed guy, Jim Rothbarth, who was an amateur racer. I spent some time giving him some coaching, and he got as far as doing the Daytona 24 Hours. Before the race Jochen Mass found himself standing next to Jim and, because Jochen is a friendly guy, they started to chat. A common topic before the start of a long-distance sports car race is which driver is going to do the first stint. So Jochen, making polite conversation about Jim’s team, said: ‘Who’s going to start the race?’ And Jim said, ‘Gee, Jochen, I’m kinda new to this game, this is my first 24-hour race. But I think it’s the guy with the flag’.

“Satellite TV was new then and Jim made satellite dishes, so he had money pouring in. He backed me for a seat with Forsythe. I found Indycars heavy and hard on tyres, and with the turbo you had to control the power and be sensitive with the throttle. But my sports car experience helped with that, and on road circuits it was almost like driving a sports car. On ovals I wasn’t so happy initially. I did my rookie test at Phoenix, which is a one-mile oval, but at those speeds it feels tiny, like you’re going to disappear up your own exhaust pipe. But on the road and street circuits I did okay: I was fifth at Laguna Seca, and at Miami I led until I screwed up and went off.

“For 1986 I was approached by Mike Curb, the Lieutenant Governor of California, who was backing Dan Gurney’s Indycar team. They signed me up for the year, and all of sudden I wasn’t hunting for sponsor money, I was being paid to drive. In my first five races I was in the top 10 three times – and then Gurney and Curb split up and the financial tap was switched off. When we went to Indy we knew from the beginning that we weren’t going to make it. They got a seasoned Indy racer to try the car. He went 1mph quicker than me, and he told them, ‘Your driver is not the problem, the car is the problem’. After that I tore up my contract with Dan and said, ‘Let’s just forget about it’.

“All this time – quite a contrast to Indycars – I had a Renault contract to race in their R5 Turbo series, and I won it in 1983 and ’84. I won the Monaco R5 race supporting the Grand Prix three years running. To win at Monaco is nice, even if it’s only in a little hatchback. I also did the Macau F3 race four times, finished second once and third twice. I loved that Macau circuit. To set a quick time and not throw it in the wall you had to be really accurate, get very close to the barriers. Glenn Waters, when I was driving there for him, put grease on the sidewalls of my tyres, and after qualifying he said that most of the grease had been rubbed off.”

Satisfying 1990 Daytona 24 Hour win with Jaguar and TWR

Motorsport Images

There were other drives, such as a couple of one-off outings for Tom Walkinshaw’s Jaguar team in their XJR-6s at Brands Hatch and in Malaysia, but both ended in retirement. For the 1986 Daytona 24 Hours Jan joined the BF Goodrich Porsche 962 team along with Derek Warwick and Jochen Mass, but around dawn his rear brakes failed and he crashed heavily. He was trapped in the wrecked car, lying in a bath of fuel, before he was lifted out through the windscreen aperture.

By mid-1986, with the Gurney Indycar relationship over, Jan’s diary was suddenly empty. “I was living with my girlfriend in Huntington Beach. I thought, ‘OK, I’ve been racing for 13 years, and I always thought I was pretty good. If that’s true somebody will come and find me. If nobody calls, then I’m not as good as I thought I was’.

“And nobody called. I just played golf for two and a half months. Then suddenly the phone goes and it’s Roger Silman, team manager for Tom Walkinshaw’s Silk Cut Jaguars. Three weeks later I’m finishing third in the World Sports Car Championship round at Jerez with Derek Warwick. Three weeks after that Derek and I are leading the Nürburgring 1000Kms, until the engine blows. Three weeks after that I’m finishing second in the Spa 1000Kms with Derek, and then three weeks after that I’m in Japan for the Fuji round. That’s how quickly your fortune can change in motor racing.

“In 1987 I was paired with John Watson, and we won the championship rounds at Jarama, Monza and Fuji. We were second at Spa and Silverstone and third at Brands. Le Mans was a disaster: I was with Eddie Cheever and Raul Boesel and we had lots of problems, but ours was the only Jaguar to finish, in fifth place behind the Porsches. But almost all the other rounds went our way. In the Drivers’ Championship Raul had fewer retirements than John and I did, so he took the title with John and me joint second.

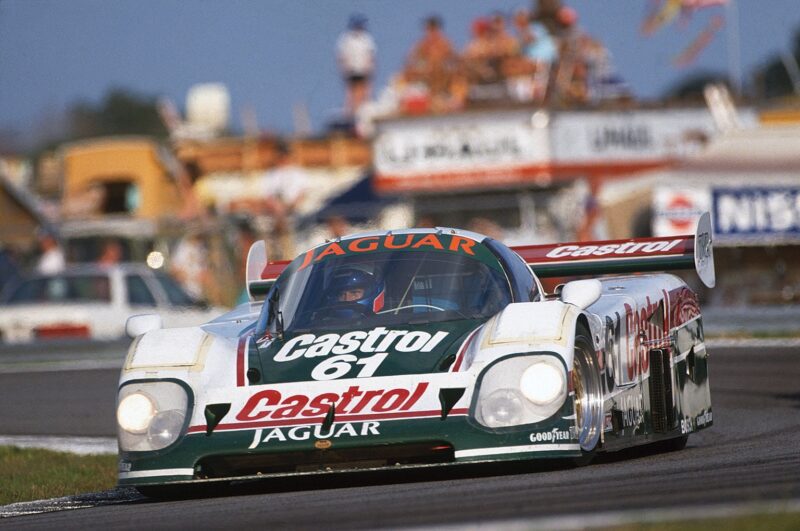

“As well as the purple Silk Cut Jaguars contesting the WSCC, there was also the American Jaguar team, in green Castrol colours, run in the IMSA series by Tony Dowe out of Valparaiso, Indiana. The rounds tended to be on alternating weekends, so I did 23 races for Jaguar that year, criss-crossing the Atlantic as well as going to Japan and Australia. In the FIA races I was with Johnny Dumfries and in IMSA it was Davy Jones, but I also did a couple of races with Martin Brundle. We were second in the Spa 1000Kms together, and in the final IMSA race at Del Mar I led from the start and handed over to Martin who led to the finish. And I did a stint in the winning car in the Daytona 24 Hours, along with Martin, Raul and John Nielsen.

Monaco hat-trick in Renault 5 Turbos

Motorsport Images

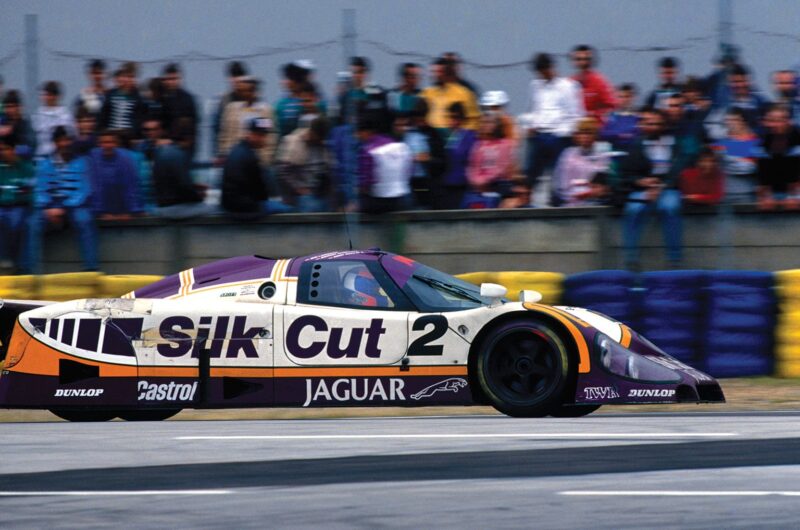

“Then there was Le Mans. Johnny and I were joined in our car by Andy Wallace, and Eddie Hinckley was our chief mechanic, a fantastic guy. Before the race we lowered the car slightly at the back, a crucial change that gave us a bit less drag and made us faster than the other Jaguars in a straight line. I told Johnny and Andy I was going to start quietly and not get mixed up with the racing at the front. But the car was so quick on the straight I could do nothing else. I was sixth on the grid, second at the end of lap one and in the lead by lap six. We pretty much led the whole race, even though I had to stop at 6am to change a badly cracked windscreen. The other two Jaguars dropped out.

“Then, with barely a couple of hours to run, changing up from second to third, Waaaang, the revs go sky-high, no gear. I knew Raul had already retired his XJR-9 with no gears. I tried fourth and it went in, so I decided: ‘From now on I’m not going to touch that gearlever’. I stayed in fourth for the rest of the race. We’d been doing almost 250mph in fifth, so I could still do over 200mph in fourth, but it was quite a struggle chugging around the tight corners. I didn’t want to say anything on the radio, because I knew that the other teams were monitoring our frequency, and Hans Stuck’s Porsche wasn’t far behind. If Hans knew the trouble I was in he’d go flat out to catch me.

“I came in for my last refuelling stop and had to splutter away in fourth gear. It took me the whole length of the pitlane to get the clutch out, and they must have heard the trouble I was in. You don’t know how relieved I was when 3 o’clock came around and the chequered flag came out. Stuck was just 2min 36sec behind.

In 1994 Walkinshaw persuaded Lammers into BTCC Volvo estate

Motorsport Images

“It meant such a lot to the team, and to everybody. In the 1950s Jaguar won Le Mans five times in seven years, and now, after 31 years, Jaguar had won again. It was a big, heavy car, with lots of downforce. It was Andy’s first endurance race, and at one point during the night he was completely worn out. So I did 13 of the 24 hours, I started it and I finished it. We kept quiet about the gearbox problem and how difficult my last stint had been. None of the journalists picked it up, so it never became generally known. After the race, when Tom’s crew took the gearbox apart, the primary shaft fell out of the casing in two dozen pieces.

“I was on a high with Walkinshaw and Jaguar, driving a great car for a great team, great people in a great environment. And I was earning good money – in 1988, doing 23 races on both sides of the Atlantic and winning Le Mans, I guess I earned about £300,000. Tom and Roger Silman always knew how to get the best out of me, and I owe them a lot. Tony Southgate too, who’d designed the car: clever, approachable, and a real sense of humour.

“I was always the team jester. Sometimes you’d walk into a briefing and it was like a funeral was going on. Tom was usually pretty stern, but I’d try to make him laugh. I’d say, ‘Hey Tom, who’s this?’ And I’d pull a face. And he’d groan and say, ‘I don’t know, who is it?’ And I’d say, ‘It’s me!’ He’d raise his eyes to heaven and say, ‘Why am I paying this guy to be in my team?’

“I think Tom and Roger liked me because I was low-maintenance, I never complained. Martin Brundle and Eddie Cheever – I’m sure they’ll forgive me for saying this – were the prima donnas in the team, never happy. Even if they were fastest they always wanted to go quicker. That’s a great attitude, it helps the team to do better, and they were an asset because of it. But sometimes Tom, to make a point, would put me in their car and, with all my joking around and my nonsense, I would be as quick or sometimes quicker.

Dome brought two sportscar titles

Motorsport Images

“But I got on very well with Martin. I was the Dutch guy, informal, outspoken, jokey. He was the English guy, serious, playing his cards close to his chest. I could never forget that he stood up to Ayrton Senna in his F3 days. He was a great racing driver and a great team-mate.”

So what does Jan think are the qualities that make a good endurance driver? How does it differ from Formula 1? “Well, there was a time when F1 was also an endurance race, and not just in the days of Moss and Fangio, when Grands Prix lasted over three hours. In the early ’80s it was a real workout, and sometimes a driver couldn’t make it to the end of the race – remember Mansell and Piquet in hot weather races, with their heads lolling around in the cockpit because they were worn out. A good endurance driver has to be very fit, of course, and I worked hard on that: running, kick-boxing, karate, especially sports that taught me to ignore pain or discomfort. And if you’re doing 25 or 30 long races a year that helps to keep you in shape. In endurance racing if your driving is too tense, if you have to wring the car’s neck to be quick, however fit you are you’ll wear yourself out. And you’ll wear the car out too.

“In 1989 I combined the European and American calendars again, with some good results including wins at Portland and Del Mar again. My co-driver was often Patrick Tambay, a real gentleman, and I did Le Mans with Patrick and Andrew Gilbert-Scott. We had a puncture on the very first lap, would you believe, then came through from dead last to lead by 1am. Then a blown oil seal leaked all the oil out of the gearbox. The TWR guys changed the whole back end in just under an hour, and we climbed back to finish fourth. In 1990 Davy, Andy and I won the Daytona 24 Hours, and at Le Mans Andy, Franz Konrad and I came second in a Jaguar 1-2. We lost a lot of time having a new nose, door and screen fitted after Franz crashed at 5am.

Running the Dutch A1GP team had promise, until the series collapsed

Motorsport Images

“I did 95 races for Jaguar over those four and a half years. Then, with the turbo engines coming in, and after so long with one team, I thought it was time to move on. Toyota was setting up a sports car programme and offered me big money, so I went with them. In 1991 we did a lot of testing but the car wasn’t ready to race, so I filled in doing Japanese Formula 3000 for Dome, which was great fun, against Schumacher, Irvine, Herbert, lots of good guys. When the Toyota got going in 1992 Geoff Lees, Teo Fabi and I were eighth at Le Mans, and Geoff and I won the Japanese championship.

“Now, at 47 years old, I became what you might call a bread driver, or a racing prostitute. I needed the money, I needed the drives, and I made it my policy to say yes to everything. I did F3000 in Europe in 1993 with Il Barone Rampante, and then in 1994 I was back with Walkinshaw, in touring cars after nearly 20 years. Tom talked me into a Volvo estate car, and the first time I drove it I thought, ‘Thank God I only signed for a year!’ Since then the list of cars I have raced is a long one: Porsche, Audi, Lola, Ferrari, Spice, Dome, Lotus, Courage, Panoz, Nissan, Bitter, Mustang, Corvette, ORECA, Lamborghini, Doran, and some more I’ve forgotten. I have now done Le Mans 22 times: it would be nice to do two more, to make it 24. In 1996 I was there in a Courage co-driving with Mario Andretti and Derek Warwick. Mario is so laid back, so relaxed: he can talk with equal focus about the most complex things, and about the most trivial things. We had lots of problems but we did finish. It was a huge privilege for me to drive with such a great man.

2011 was his 22nd Le Mans – and he says he’s not finished yet

Motorsport Images

“Derek Bell is another: he and Andy and I did the Sebring 12 Hours in 1995 in a Spice-Chevrolet, and we won it. But somehow the official timekeepers counted our last two laps as one lap, and decided we were second. Derek was the ultimate endurance driver: stable, confident, uncomplicated, never moody. At dawn, at night-time, early or late in the race, he was always the same, consistent in his attitude and approach. And he was fast.

“So many others I raced with: from Stefan Johansson to Danica Patrick, from Allan McNish to Perry McCarthy. Perry would always arrive for a test in a car that looked as though it had cost £50. I twice did the Daytona 24 Hours with Tony Stewart, the multiple NASCAR and Indycar champion: in 2005 we finished third in a Crawford-Pontiac. Driving with Tony was another memorable experience. He’s a real competitor, a pure racer. He’s one American who, if you brought him into F1 today, he’d be a front-runner.

“The Nissan GT1 project put me back with Walkinshaw: lovely car, but way under-powered. We got sixth at Le Mans with it in 1998, with Erik Comas and Andrea Montermini. Another strange project was with Toine Hezemans, who is a great salesman: if he wanted to murder somebody he’d talk them into committing suicide. He persuaded Erich Bitter to build us up a little Lotus Elise with a huge Chrysler V10 engine. Not a good idea.

Lammers shared historic 1998 Jaguar Le Mans win with Dumfries and Wallace

Motorsport Images

“In 2000 I set up Racing for Holland, and through my old contacts with Dome in Japan we got their new Le Mans car with Judd V10 engine. The FIA Sports Car Championship replaced the old World Sports Car series, and we were third in that in 2001. Then we won the title two years running in 2002 and 2003, with wins from Monza to Nürburgring to Brno. We raced that Dome for seven seasons, with updates: did Le Mans seven times, finished five of them, with a sixth, two sevenths and an eighth. Not bad for one car. But we were always on a tight budget and low on sponsorship – at one stage I resorted to dividing the paint scheme up into panels, and selling panels to everybody I could persuade to come in.

“In the end Racing For Holland nearly dragged me into the ground. I managed to wind it up without going bankrupt, paid off the banks, did a deal with the taxman, and my creditors have all been very patient and understanding. It’s all pretty much sorted now.

“When A1GP started in 2005 I ran the Dutch effort under the RFH banner, with Jeroen Bleekemolen, Jos Verstappen, Robert Doornbos and others. In the third and final year we were fourth in the series. The idea was great, the format was great, and potentially it was the best thing that could have happened to motor racing. Tony Teixeira put his own balls on the line, and fought to the bitter end. The trouble was he thought he could get it going for £200 million and he needed £400 million. It was my job to publicise the series in Holland, and for the Zandvoort race we had 100,000 paying spectators over the three days. In F1 Bernie deals with the big companies and the politicians, and doesn’t care about spectators. They’re just there to make the TV pictures look good.

“I still get to do the odd race: I did a Scirocco Cup round for VW in Moscow recently, got pole but muffed the start totally. Got back to second, just failed to catch Nicola Larini by the flag. I’ve done the Mille Miglia in a Porsche 550 Spyder, a Bugatti, an XK120 and a Porsche, and I did the Carrera Panamericana in a Porsche 356. I’ve done five Dakar off-road rallies in South America, not in a car but in a thousand horsepower, eight-ton Ginaf truck. I’ve run a couple of New York marathons – I got under 3 hours 50mins – and also I race a sulky, a lightweight two-wheeled cart drawn by a galloping horse. That’s quite exciting.

“Looking back just at my F1 career, you might think I have regrets. I have absolutely no regrets. I think I was quick, but I wouldn’t have been a Senna. Maybe I would have been an Irvine, or a Barrichello. If everything had worked out, maybe I’d be pissed off because I only ever finished second in the world championship, because I got a puncture in the last round or something. I have seen so many people in motor racing who are dissatisfied for the rest of their days because they do not achieve their ambition. I’ve had a wonderful life, doing for 40 years what I love to do. I’m very happy with that.”