No Lunch With... Richard Petty

A quiet superman who doesn’t brag about his 200 NASCAR wins, his seven championships or his charity work for disabled children

Jessica Milligan

The great perk of this job is the privilege of getting to know, often quite well, so many talented, single-minded people who have carved out great careers in the cockpit, at the drawing board or in the pits. In doing so they’ve earned the respect of enthusiasts who understand that there is far more to motor racing than is seen by the general public in their weekend living rooms, imprisoned behind the rectangle of a television screen.

Quite apart from all those fine players, you occasionally come across a racer who stands out as being, in some indefinable way, on a different level from the rest. Away from the track this individual will tend to be quiet, distancing himself from the media hype and razzmatazz. In private life he may avoid the material trappings of success. Yet when he walks into a crowded room the buzz of conversation will die briefly, as everyone becomes aware of his presence. And when he is at the wheel, doing what he was born to do, sometimes his efforts will reach an almost superhuman level, increasing the illusion that he is not quite of our world.

Juan Manuel Fangio, whom I was lucky enough to meet late in his life, had that indefinable quality. His manner was gentle and he spoke little, yet his eyes seemed to probe deep into you. Certainly, when his unobtrusive figure walked into the room everybody went a bit quiet. You couldn’t separate the man from his achievements. Mario Andretti is another who, when you meet and talk with him, seems to be set apart from his peers.

Early in Ayrton Senna’s F1 career, when he had just signed for Lotus, I spent most of a day with him. With a little pressure from John Player he’d agreed to a BBC TV interview, and I was lucky enough to be holding the microphone. His first F1 season with a lesser team, Toleman, had produced three miraculous podiums and given an indication of the greatness to come. During the interview he was professional and serious, unsmilingly considering my questions before giving intelligent, in-depth answers. Already he had that slightly other-worldly demeanour that later became so familiar.

Now another has joined my personal short list of quiet supermen. Back in 1971, as a Limey journalist on my first visit to a NASCAR race – the Daytona 500 – I was introduced to Richard Petty, already known as The King after an astonishing 100-plus victories in eight seasons. He was getting ready for the race (which of course he went on to win), so unsurprisingly I got a polite but monosyllabic greeting.

Fast forward 43 years, and I decide that the readers of Motor Sport deserve a Lunch With… feature on the man who was NASCAR champion seven times, won 200 races and scored more than 700 top 10 finishes – an unbelievable 513 of them on the trot. That last statistic speaks volumes about his intelligence as a racer, and the preparation skills of the team he gathered around him. It’s not easy to set up our meeting because, at the age of 76, Richard Petty still leads a very busy life. And he declines lunch, which is not a meal that plays any part in his daily schedule. But eventually I find myself in rolling country north of Randleman, North Carolina, in a little village called Level Cross.

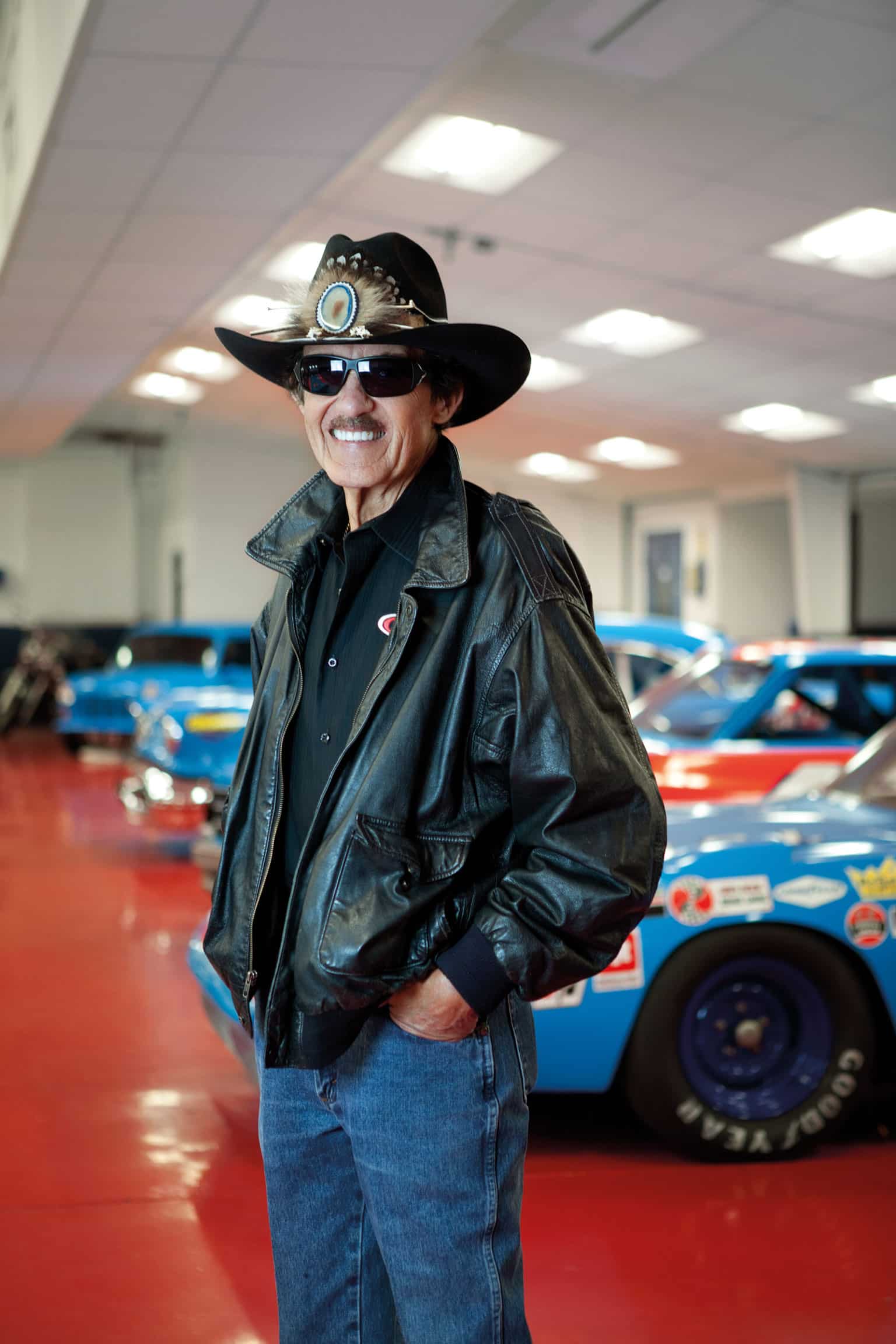

Opposite his grandfather’s humble wooden house where Richard was born in 1937, the workshops of Petty Enterprises now cover a wide area. As I look over the museum line-up of some of the winning cars that have worn that distinctive pale blue colour and that number 43, a tall, upright, rangy figure comes in and shakes my hand with a quiet “Hi”. The outfit is just like all the pictures: high-heeled boots, neatly trimmed moustache, tall cowboy hat, impenetrable dark glasses. He points out some of the cars to me, reminiscing briefly about the achievements of each. One, with severe damage and most of the front apron missing, is the Pontiac he drove in his final race. Caught up in a mammoth pile-up before half distance, he pulled off with his car on fire. Marshals put the fire out and his crew worked feverishly to make it driveable, and with two laps to go he rejoined in the battered wreck to come home, yet again and for one last time, a finisher.

Then we go to his office, unpretentious but with the walls lined with pictures from a crowded life: not just of racing incidents and racing folk, but also Richard with American presidents, film stars, State governors. I’m offered a cup of coffee while Richard sticks to chewing tobacco, as he has done all his life, a paper cup close at hand for the spit. After years of big-block open-exhaust V8s his hearing isn’t great, but if he misses a question he says, “Sir?” with quiet courtesy. As we start talking through an extraordinary career – as a childhood mechanic, then 15 seasons as a top driver, then as a team owner – his slow drawl carries not a trace of arrogance, self-satisfaction or bias.

The Pettys, Carolina country folk for generations, did a bit of everything, from farming to sawing logs. Lee Petty, Richard’s father, hauled lumber and, at one stage when money was tight, lived with his wife and two sons, Richard and Maurice, in a two-room trailer with outside toilet. In the summer the whole family worked in the tobacco fields. The boys and their cousin Dale Inman raced around on bicycles and home made soapbox cars, and Richard found he could beat the others if he unobtrusively greased the axles of his soapbox – an early lesson in race preparation.

Lee, since his teens, had been racing his stripped Model T Ford around the back roads, and at night when the police were abed he’d challenge locals for increasingly large bets. In 1947 he parlayed the proceeds into building up a ’37 Plymouth with a Chrysler straight-eight flathead, and started winning local dirt-track events. “If my daddy won, he was happy. If he finished second, he wasn’t. Once I said, ‘Well done, Daddy, you finished second.’ And he said, ‘Richard, there ain’t no second place. Either you win, or you lose.’ I never forgot that.”

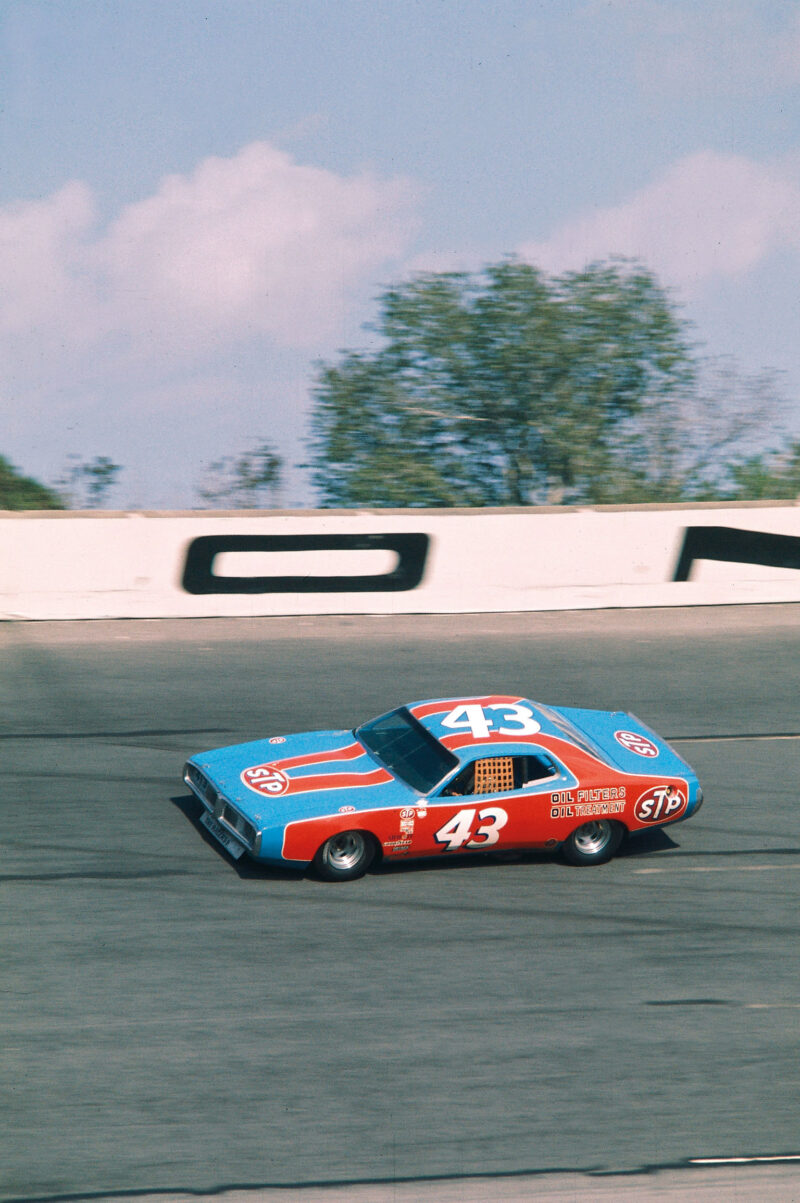

Richard Petty’s famous 43 was one up on his father, while even STP money couldn’t fully replace his Petty blue livery

Motorsport Images

In 1949 the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, newly set up by Bill France, promoted a race at the Pettys’ nearest city, Charlotte, with a purse of $6000, an unimaginably large sum. It was run to late-model rules, so Lee borrowed a 1948 Buick. “We drove it to Charlotte, went to a filling station, put it up on a ramp, changed the oil, greased it, took off the muffler, and wrote the race number on the side with shoe polish. That’s how stock it was.” In the race Lee was just about to take the lead when the suspension broke and the car flipped four times.

Having made his peace with the car’s owner, Lee bought a cheap Plymouth and hit the NASCAR circuit. That first year he ended up second in the championship. Richard, now aged 12, was the nearest Lee had to a mechanic.

“I could hardly get through each day at school waiting for the next race. And each evening, when my homework was done, I was in the garage. I started by keeping the car clean – which, racing on dirt, was a big job – plus easy stuff like packing the wheel bearings. As I went along I learned how to change parts, work on the motor, do springs and shocks. NASCAR was developing from purely stock to things that made the car safer and also things that made it faster, and I learned along with it. As NASCAR grew up, I grew up. But I never thought about driving one day. I just wanted to work on the car best I could, then Daddy could win and he’d be happy.

“We towed the race car on the road, so I sat in the race car and steered. The tow car didn’t have much brakes, so I had to watch for when Daddy held up his hand and I had to hit the middle pedal. I was the brakeman. Sometimes he wrecked the race car and, towing home, the wheels were all out of line, so I’d just hold the lock on and Daddy would drag me home. At the races no kids were allowed in the pits, but I was tall for my age, and if need be I’d get past the gate hiding in the boot. And we’d keep old passes, doctor the date and I’d wear those. If ever there was a kid who grew up doing what he wanted to do, it was me.”

In 1954 Lee won the first of his three Grand National championships. NASCAR racing was still pretty rough: at Charlotte once, after Lee and Junior Johnson took each other off, they clambered from their cars and started a serious fist fight. “In the end the local chief of police got his men to break it up. Daddy and Junior both said: ‘What did you stop us for? We wasn’t hurtin’ nobody’. There was another time when Daddy and Tiny Lund got to arguing. Tiny was about the size of the state of New Jersey, but Daddy punched him in the eye and wrestled him to the ground. Then me and my brother jumped on Tiny, and Mother started hitting him over the head with her handbag. Tiny gave up then. He said, ‘When you take on a Petty, you have to take on the whole family’,”

Richard had been driving since he was five, standing up on the hay wagon in the fields, and on local country roads as a young teen. The local police turned a blind eye because they’d bring their squad cars to Lee Petty to have him tune their engines. “Then, when I got to be 17, I did think about racing and asked Daddy about it. He said, ‘Come back when you’re 21’. When that came around I asked Daddy again. All he said was, ‘That Oldsmobile over there, get it ready’.” Richard chose number 43, because it was one up from his father’s 42. “When we got to paint the car it was the middle of the night and we couldn’t go to the store to buy no paint. We had half a can of blue and half a can of white. So we mixed it up and used that, and we thought it looked pretty good.” The distinctive shade of Petty blue was born and continues to this day: it’s now copyrighted.

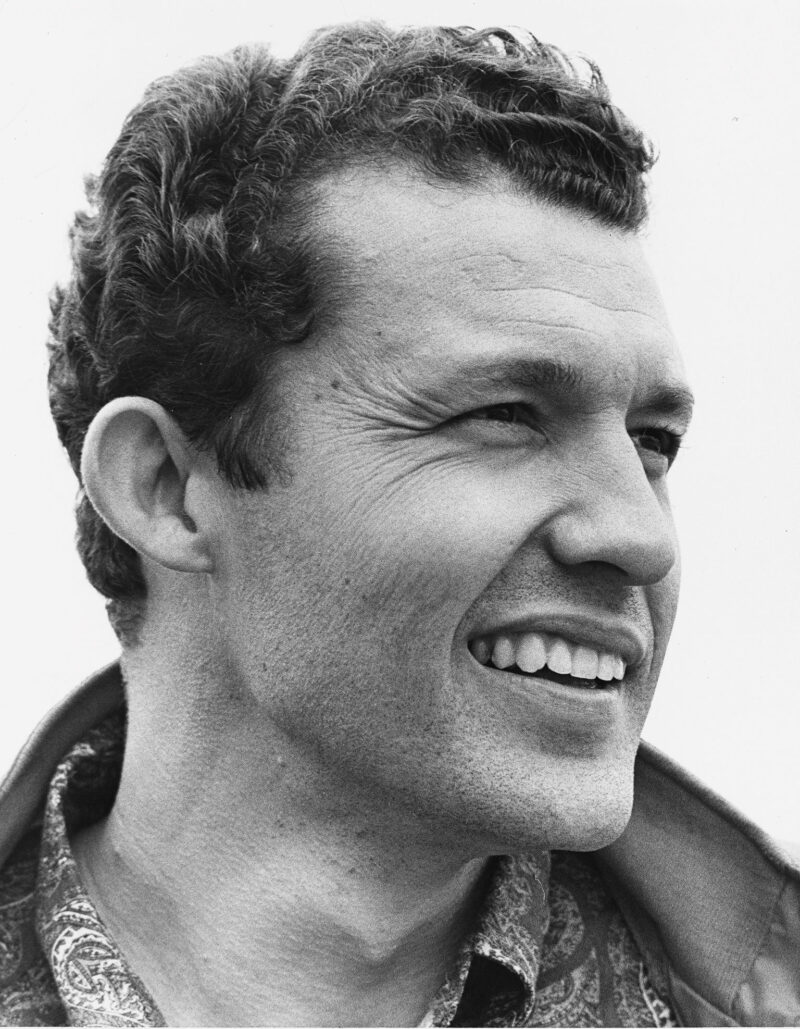

There have been four generations of racing Pettys. But Richard remains king

Motorsport Images

Richard’s first race was on dirt at Columbia, South Carolina, in July 1958, a couple of weeks after his 21st birthday. He finished sixth. In 1959, his first full season, he got his maiden win. “It was 150 miles at Lakewood, a fairground dirt track in Atlanta. It got so dusty and rough you didn’t really race anybody, you just ran and hoped you’d get to the end. They flagged me the winner and I went to the winner’s circle, and then they told me another driver had protested that the flag had been hung out a lap too soon. He’d done another lap, so they took my win away and gave it to him. The protestor was Daddy. Because he was running a ’59 and I was only in a ’57, he was in line for a factory bonus of $500 if he won. Back then $500 was a bunch of money. Only just about buys you a sandwich and a Coke now.

“I never showed how disappointed I was, but I got over it the next time I got in a race car. When you fire up that engine, the past is all gone, and it’s the next race that counts.” And his first real victory came a few weeks later at Columbia. With that, plus six top-five finishes and nine top 10s, Richard was named Rookie of the Year. By 1960 he was already a major player, finishing Grand National runner-up with three wins and a string of consistent placings. That year Lee was sixth.

Daytona 1961 was bad for the Pettys. In the first 100-mile qualifying race before the 500, Fireball Roberts and Junior Johnson were slipstreaming for the lead at 160mph, with Richard in their wake, when Roberts lost it.

In the ensuing mayhem Richard’s Plymouth cartwheeled over the top of the banking and fell 40 feet to the ground. He escaped with a wrenched ankle and eyes full of shattered windscreen glass. After a circuit doctor had spent an hour removing the shards of glass Richard was limping back to the paddock when he heard the commentator announce a big crash in the second qualifier. In an identical shunt, three cars had tangled on the banking and Lee had gone over the wall. He was pulled unconscious from the wreckage with internal bleeding and a punctured lung.

“After four months in hospital Daddy had a few more runs, but he didn’t enjoy racing any more, said it had just become like work. So he turned away from everything and passed the team over to my brother and me. I was doing 40 or 50 races a year. I built the cars in the winter, I worked on them during the summer, I drove the truck to the track, and I was running the business. I’d done some classes when I was 18 to learn about book-keeping, but the rest of it was the school of hard knocks.

“But here’s what I got to say. I always had great people to help me. Without them I wouldn’t have been anywhere. If I win a race or win a championship, how many people does it take to make that happen? You can’t do anything by yourself. The only thing you can do on your own is use the bathroom. Take my cousin Dale Inman. We grew up together here in Level Cross, raced our soapboxes together as kids. He was with me from my first race, he ended up as my crew chief.”

Having been runner-up in the Grand National series twice more, in 1962 and 1963, Richard won his first title in 1964. One of his victories that year was the Daytona 500, which felt especially sweet. He would go on to win this keynote race a total of seven times. His 1964 Plymouth benefited from the latest Chrysler Hemi engine, but for 1965 NASCAR banned the hemi. Chrysler withdrew from NASCAR in protest and, as Petty had a rolling Chrysler contract, they decided to send him drag racing. “We built up this little Barracuda, we put 43 Jr on the side, and we were doing 140mph in the quarter-mile and beating just about everybody in the class.” Then at an event in Georgia something broke, and the Barracuda veered into the poorly protected crowd. Among several injured spectators, an eight-year-old boy died. Richard was quietly devastated and pulled out of drag racing as soon as he could. “For 1966 NASCAR allowed Chrysler to run the hemi with a smaller than seven-litre capacity, and we still won eight rounds and got third in the series.”

Petty HQ includes a museum. This is his 9173 title-winning Pontiac GTO

Jessica Milligan

Then came 1967: a big year, with AJ Foyt, Parnelli Jones and Mario Andretti driving for Ford, while Richard led the Chrysler arsenal with the number 43 Plymouth. There were 48 rounds of the Grand National Series, and Richard likes to say he lost 21. But that means he won 27, 10 of them on the trot. It was the most extraordinary domination in NASCAR history. A lot of Richard’s now very substantial winnings were spent on building and equipping big new workshops at Level Cross.

“You see, our focus was racing, 24 hours a day. Maurice, Dale and me, we had no outside activities, no other business, no hobbies, no holidays, it was just race, race, race. As soon as each chequered flag waved we focused on the next one. It was like we was wearin’ blinders.” That’s what US farming people call the blinkers that horses wear to stop them straying from the job.

“Ford was always coming after me, but we were really deep into our Chrysler deal. Then we found out that Chrysler was doing a wing car badged as a Dodge. So we went up to Detroit and said, ‘What’s Plymouth doing like this?’ They said, ‘Nothing. That’s a Dodge, you’re our Plymouth man’. I said, ‘If you don’t give me a wing car I might go across the street’. They didn’t seem to believe us, so we knocked on Ford’s door, and at once we had a deal with Ford for ’69. Ended up second in the championship. I won nine races for them that year, including Riverside, which was a road course. I loved road courses. When I started I ran a lot of dirt races and I always thought on a dirt oval a driver could express himself. On asphalt if you get sideways it slows you down, but on dirt that’s how you run. And road courses were more like dirt races. Dirt’s long gone now. The last [top-division] NASCAR race on dirt was at Raleigh, 44 years ago. I won that.

“Anyway, Chrysler realised they wanted us that much worse now, and the head of Plymouth came right down here to Level Cross himself. Didn’t bring no lawyers, didn’t bring nobody. Just said, ‘What will it take to get you back in a Plymouth? I said, ‘Give me a wing’. So they did the Plymouth Superbird.” In the five seasons from 1971 to 1975, Richard was Grand National champion four times with 58 victories, and his prize money over that period exceeded $1.8 million.

Even so, from 1972 Chrysler cut back their factory involvement, and Richard needed a sponsor. Drinks firms were out: he’d promised his mother he’d never earn money from alcohol. Throughout his career, when he took a pole position, he never collected the Budweiser bonus that went with it. So now he talked to STP’s larger-than-life boss Andy Granatelli, who was keen to promote his oil additive. But any STP car always had to be painted in its flame red/orange colours, and Richard wasn’t having that. It was Petty blue or nothing. After an all-night negotiation session a compromise was reached: the Plymouths would remain blue, but with flame red side panels. Undaunted, Granatelli snuck into the small print of each year’s contract a paragraph offering a further $50,000 if the cars were all flame red. Each year, Petty struck it out.

1957 Oldsmobile was the king’s first ride

Jessica Milligan

“Chrysler let us take over their Dodges too, and we found the Dodge was a better shape on the super-speedways than the Plymouth. We didn’t know much about aero then, it was before we started going to wind tunnels. So we ran Plymouth on the short tracks but we converted our speedway Plymouths to Dodges.” At this stage the one driver who seemed regularly to be able to take the fight to Petty was Ford’s David Pearson. “David was my closest rival. Lots of races either I was going to win or he was going to win. In something like 63 races we finished first and second. I think I won 31 and he won 32. Most of them came down to the last lap. It didn’t hurt so bad to lose to David because I knew how good he was – good on dirt, good on asphalt, good on road courses. He was a smoker: he had a lighter in the car, and when there was a caution flag you’d look in the mirror and see him light up and puff away. But not when the race was on, he was too busy.

“At Daytona in ’76 I’m leading with David right there. I know he’ll try to draft past on the last lap, so I start letting off the gas a tad, not on the corners but on the straights, instead of 7500rpm I’m pulling maybe 7250. Then, come the last lap, I go wide open to try to pull away. But at the end of the back straight he gets the draft and he passes me, goes into the corner 10 or 12mph faster than the laps before, gets out of the groove and goes high. I jump in below him and I reckon I’ve got enough draft to get back in front. I’ve worked out where he’ll be – we’re still doing almost 200mph – and I get it about six inches wrong. My left rear just catches his front. Then all hell breaks loose. At some point I hit the wall head-on, and David hits the wall and then bounces off another car which puts him straight again. He keeps his engine running, drives across the infield to the finish line, wins the race. I wind up 20 yards from the finish line with my engine stalled. But we’re so far ahead of everyone else I get second place, a lap down.

“They were big, brutal cars, very heavy to drive on a hot day for three hours or more. You’re talking 800bhp and nearly two tons. We just had manual steering: it’s power steering now, you can drive them with one hand. Plus they have personal trainers making sure they do the right exercises and eat the right stuff. We just raced, and when we weren’t racing we worked on the cars. And now they have air-conditioning feeding into full-face helmets. In a race in 1962 the exhaust leaked into my car and I got gassed real bad with carbon monoxide poisoning. The effects stayed with me, and after that sometimes on a hot day they’d have to pull me out of the car during a pitstop, give me oxygen, and put me back in. I still get trouble from that even now.”

Even Mini Van is Petty blue

Jessica Milligan

Having won his seventh Grand National title in 1979, Richard had a big accident at Pocono when the front wheel broke and sent him into the wall. “I turned over a few times, and after they got me on the stretcher I said, ‘I think I broke my neck’. In the hospital the doctor said, ‘Yes, you have broken your neck. But we can see from the X-rays it’s not for the first time. When did you break it before?’ News to me. Must have been in an earlier accident when all the rest of me was hurting so bad I didn’t pay no attention to my neck.”

His 200th victory – and, as it turned out, his last – came in the 1984 Firecracker 400 at Daytona. “I was leading, but Cale Yarborough’s car had more speed and he was waiting for the last lap to draft past. So in the closing laps I did like I did with Pearson that time, easing off, easing off. And then, two laps still to go, I see a guy down at the first turn going sky-high over the infield. I realise by the time we get back to the start line the caution lights will be on, and whoever gets there first will win the race. So I get back on it, hard. Cale does too, we go into Turn Four side by side – black marks on the side of both cars afterwards – but I’m on the inside and I beat him to the line by a fender. Then, sure enough, there are the caution lights and it’s all over.”

Richard continued to race, and race hard, for a further eight years, past his 55th birthday. Then he announced that the 1992 season would be his last. He fitted in a punishing countrywide fan appreciation tour, a presentation from George W Bush when the president came to Daytona, and leading the pace lap at each race to the affectionate applause of the crowds. His last race of all, at Atlanta, included the fiery accident mentioned earlier, when he restarted to come home a finisher.

He continued to run Richard Petty Enterprises, and when his son Kyle got to be 18 and wanted to race Richard was more accommodating than Lee had been. Other drivers joined the team too. It was still seven days a week, 18 or more hours a day at Level Cross. “By now we were running three cars, and I was trying to look after the business side, sponsorship and stuff. Now there were people like Penske, Roush, Hendricks coming into NASCAR who had the big outside world to draw on. Racing didn’t have to provide their racing money. The racers I grew up with, Bud Moore, Junior Johnson, the Wood Brothers, we all raced from the inside out. These big-business millionaires raced from the outside in.

“Today’s generation is so different. Drivers are often sons of rich fathers, they’ve been racing from five years old in karts and stuff, so by 21 they’ve already got 15 years of track experience. But they’ve never had to put a car together, build it up and get it to the racetrack. They don’t know anything about that stuff. Nothing against them for that, the environment is different now. But when I started, in the old shed that was where we’re sitting, I had to learn things as they happened. When Columbus discovered America, nobody had been before. He had to learn as he went along. We were like that.”

Petty’s final race in 1992 was in this Pontiac

Jessica Milligan

Kyle Petty’s racing achievements never approached his father’s. In 30 years he did more than 800 NASCAR races and garnered a handful of wins, but being in his father’s shadow cannot have been easy. He now has a busy career hosting the NASCAR TV coverage. But his own son Adam, Richard’s grandson, was clearly destined for great things. In 1998 he ran a Pontiac in an ARCA round at Charlotte, and won it. He spent 1999 in the Nationwide series, leading 23 of his 29 races, and for 2000 he moved up to the big cars. In qualifying for the second round at the New Hampshire oval at Loudon his throttle stuck open. His car hit the wall and he was killed instantly. He was 19 years old.

The family was devastated. Lee lived to see his great-grandson race, but had died three weeks before Adam’s accident. “It was before NASCAR mandated a kill switch on the steering wheel, and before neck braces. It was a freak accident. Adam was the fourth generation of racing Pettys. He was focused entirely on racing, it was his dream, his passion. With the talent he’d already shown, and with his personality, he could have been really, really good. We were grooming him as the future head of Petty Enterprises. But the good Lord didn’t see it that way.

“Away from the track, Adam used to volunteer at a camp in Florida called Boggy Creek, where terminally ill and seriously disabled kids could get a fun activity holiday that they’d otherwise never get. It was one of a group around the US called the Hole in the Wall Gang, started by film actor Paul Newman. When Adam first visited this place and saw what it could do for kids who had nothing, it just blew him away. So he went to the bank and tried to borrow money to build a place like that up here. He told the bank they’d get all his race winnings until he’d paid it back.

“Then the accident happened. After everything had settled down a bit, we wanted to do something in Adam’s memory and we decided he should have his camp. I had 90 acres of land near here, and we talked to the Hole in the Wall people. They said they had a board meeting coming up in six months and they’d put it to the board. I said, ‘That’s no good to us. We’re going to do it right now, with or without you’. Then Kyle called Paul Newman. Paul called back next day and said, ‘Do it’.

“We went to the racing world, talked to drivers, to sponsors, to NASCAR themselves, talked to fans. They all raised their hands. One of my long-time sponsors was Goody’s Headache Powders, and they paid to build and equip the on-site hospital. Everybody got behind it. A fan who’d retired from a construction company got his buddies to come down and get stuck in. It took us nearly two years to build, spread over the whole 90 acres, and we’ve been open 10 years. Already nearly 20,000 kids who are too afflicted to go to a regular camp have visited us, 125 at a time, each staying a week. Some haven’t got long to live, others will have a severely restricted existence for as long as they remain on this earth. We try to get whole groups together suffering the same problems. Many of them have always been segregated, because they’re different. They think they’re the only one who is like that. Then they come to us and have fun with others who are like them. It changes their outlook, opens up a whole world that’s been closed before. We call it Victory Junction. Would you like to see it?”

It’s two miles down the road, in rolling countryside, an enormous site with brightly coloured buildings: as Richard says, “a Disneyworld in the woods”. The hospital, where teams of nursing staff, cardiologists, nephrologists and oncologists volunteer out of their own holiday time, is set up to look like anything but, because many of these kids have spent too much time in hospitals. Maintaining the automotive theme, it’s called The Body Shop. The dining area is the Filling Station, the snack bar is the Pitstop. Both have detailed records of each kid’s condition because diets have to be carefully monitored.

Boys and girls who have never been in a swimming pool can launch their wheelchairs into the waterpark, and kids with little or no arm and leg movement can operate the specially equipped bowling alley. There’s riding on horses that have been specially trained to be accustomed to the beeps from a child’s ventilator. One building is a huge representation of Adam’s number 45 NASCAR car, with a giant slot-car track, race overalls to try on, a car to jack up and wheels to change. In the 200-seat theatre kids who have never been able to express themselves in front of an audience can get up on stage and sing a song or tell a joke while the others cheer and clap. There’s a warming hut where the body temperature of children with sickle cell anaemia can be adjusted rapidly, an arts and crafts building, and a zoo with a variety of tame pet animals. From archery to woodworking, from fishing to miniature golf, camp director Chris Foster and his team seem to have thought of everything.

When I visit in December the camp is closed, but nevertheless it’s a hive of activity, because Richard has organised batteries of volunteers packing Christmas gift-boxes to be flown to US troops serving overseas. The goodies are all sourced in North Carolina, but the favourite for most recipients is the Richard Petty T-shirt they’ll find in each pack. Richard walks up and down the rows of volunteers with a smile and a word of thanks for each of them. Clearly Victory Junction means a great deal to him, and occupies a lot of his time. “I have four kids, 12 grandkids, one great-grandkid, and another on the way. Every one perfectly healthy. The Lord has been good to us, and we’re lucky enough to be in a position to help some less fortunate people.”

Back at Petty Enterprises, I mention that Richard is now in a position to live just about anywhere he wants. “It’s exactly because I can live anywhere I want that I live here. This is where I played as a kid, where I went to school, where I went to church, where I first worked on a car. This is where I belong. People come along, they get a bit of notoriety, it builds up their ego. So they go somewhere else and try to be someone else. I’ve never wanted to do any of that.

Petty’s cousin Dale Inman has been his right-hand man all along

Jessica Milligan

“I was county commissioner up here for 16 years, and my wife was on the schools board. Then a few years back somebody did persuade me to run for Secretary of State for North Carolina. But about that time we had a little incident. I was coming back from Charlotte one night on an ordinary two-lane road, running maybe 75 in a 65 zone, and came up behind this guy. On the corners he would slow up, and then we got to a straight bit where I could pass he’d take off. He was being a smart-butt. After a lot of this I got tired of messin’ with him, so I got up real close, and he put on the brakes, and I didn’t. So I hit him, yay hard. After that he finds a highway patrolman, and they run and catch me. This was a Democratic state then. Nothing ever came of it, but it didn’t help my campaign. Best thing ever happened, because it meant that in the end I stayed out of politics.”

That’s Richard Petty: honest, modest, quietly good-humoured. A good man. A man who started 1184 NASCAR races, and finished in the top 10 in more than 700 of them. A man who won 200 victories and seven championships. And now a man who puts his heart into a camp for desperately ill children that is his memorial to his dead grandson.

A man who has joined my short list of racing drivers who are not quite like other men.