Lunch with... Adrian Reynard

Innovator, improviser, impecunious... The founder of a famous British racing institution has been all three, but right now he's flying high once again

Motorsport Images

Motor racing is dangerous: it’s a truism that doesn’t need repeating. And motor racing can be dangerous commercially, too. On the balance sheet as well as on the track, risk can reap huge rewards but can also result in huge crashes.

Witness the fate of our racing car industry. Four months ago Britain’s longest-lived racecar builder, Lola, laid off the last of its staff and closed its doors. Previous big players such as March, and before them Cooper and Brabham, have disappeared into history, and smaller specialists from Anson to Tiga have come and gone. The only big single-seater maker that still seems to thrive is Italy’s Dallara.

It’s not long since being the world’s largest racing car manufacturer was the proud boast of Reynard. The firm’s roots go back to 1973, and through the 1980s it became extremely successful. In 1991 an attempt to move into Formula 1 brought the company to its knees; yet by 1996, having moved into Indycar racing, it was making massive profits again. But in early 2002 it went bankrupt. No company history better demonstrates the volatile nature of the motor racing business.

However the Reynard name hasn’t disappeared completely; and it certainly hasn’t disappeared in the energetic shape of the man who gave his name to the company. Now 61, Adrian Reynard is as busy as ever, heading up the Auto Research Center in the USA and doing technical and design work for major road car manufacturers around the world. To pin him down I had to wait until he flew in to Heathrow on a Sunday morning red-eye from Detroit, and then drove up to Oxfordshire to meet me at one of his favourite pubs, the Nut Tree at Murcott. Landlord Mike North, once the youngest chef in the country to earn a Michelin star, served us a proper Sunday lunch: English roast beef and Yorkshire, preceded by Loch Duart smoked salmon, and sticky toffee pudding for afters. Adrian’s choice of Argentinean Tupungato Malbec made a fine accompaniment.

Seven-year-old Reynard admires Bueb’s Connaught at the 1958 British GP

Adrian Reynard

Cars, motor sport and engineering are in Adrian’s genes. His great-grandfather was a 19th century blacksmith who moved into horseless carriage repairs at the dawn of motoring. His grandfather and great-uncle were motorcycle racers in the 1920s: GreatUncle George was a works rider for Royal Enfield, and came fourth in the 1927 Junior TT. His parents met in 1945 at one of the wartime De Havilland aircraft factories, where his father was an apprentice and his mother, remarkably for those days, worked on Mosquito upgrades in the drawing office.

When Adrian was nine Great-Uncle George gave him a 49cc four-stroke Mercury Mercette moped, and he wore a groove in the family lawn doing endless laps. “I found that by undoing two 7/16th nuts I could take the rocker cover off and watch the tappets working. I thought I was stripping the engine down. By now my dad was working for BP on fuel systems and used to bring home all sorts of exotic cars — Daimler Dart, Alfa Sprint Veloce, Aston DB4. Then he was posted to New York as BP’s US racing manager, and we lived in Connecticut for two years. He took me to the 1963 US GP at Watkins Glen. Thirty years later, when Jim Hall bought his first Reynard Indycar chassis, I showed him a picture of his LotusBRM on the grid that day, with a 12-year-old boy standing beside it — me!

“I mowed lawns for a dollar an hour and saved up enough to buy my first kart. That came back to England with me and I raced it in Cambridge Kart Club events at Kimbolton and elsewhere. I was always taking old cars to bits, hauling out engines and gearboxes and trying to find out how they went back together. I wanted a Saturday job, and almost opposite the gates of my school was the workshop of George Brown, the great motorcycle record-breaker renowned for his exploits on his huge Vincents, Nero and Super Nero. I was 15 and he was pretty dubious about hiring me, but in the end he let me spend my Saturdays there for nothing, unpacking crates and sweeping up. He taught me how to weld, and I earned some cash making some not very brilliant garden stands in the evenings and then selling them to the local ironmonger. Eventually George took me along as a helper at his speed-record attempts.

“In my A-levels I did well in physics and engineering, but failed maths. I didn’t have a good maths teacher and I never really understood it. Even today I have a problem with the intricate stuff: it’s always been the empirical side that got me through. So I was lucky to get a four-year HND sandwich course with British Leyland — half the year working in Morris Motors at Cowley and half the year at Oxford Polytechnic, which is Oxford Brookes now. I loved that apprenticeship, it was magic for me.

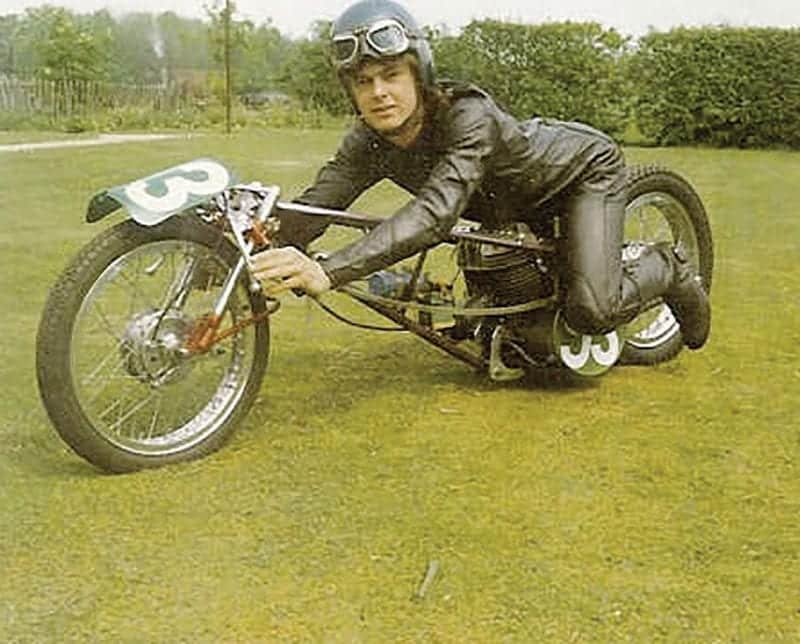

“When I was 19 George sold me an old 250cc Royal Enfield GP5 racer and I attacked some records myself at Elvington. I made up a detachable sidecar, so I could run in two classes and get twice as many runs, and broke five world records. The following year I built my own ultra-low frame with horizontal riding position, and I sprinted and drag-raced that. But back at Elvington I was plagued by a misfire on the longer runs. I couldn’t figure it out. The timekeepers were packing up to go home, but Denis Jenkinson of Motor Sport was there and took pity on me. He persuaded the timekeepers to wait while I found the trouble: over the longer distances the fuel pipe wasn’t big enough to fill the float chamber. I rigged up a bigger pipe and did my runs just as it was getting dark. And I got another bunch of world records, including the flying mile and flying kilometre.

“At college my welding bottles came in handy, patching up students’ rusty bangers in the car park for £1 an hour. I also started a car club, and one of the activities I organised was a visit to March at Bicester.” March Engineering was then only in its second full year. The little group of students was shown around by Bill Stone, the New Zealand ex-racer who’d been March’s first employee, and Bill took a liking to the bright, enthusiastic youngster. A few months later, when Adrian got a good price for one of his sprint bikes and decided to go fourwheel racing, he asked Bill’s advice.

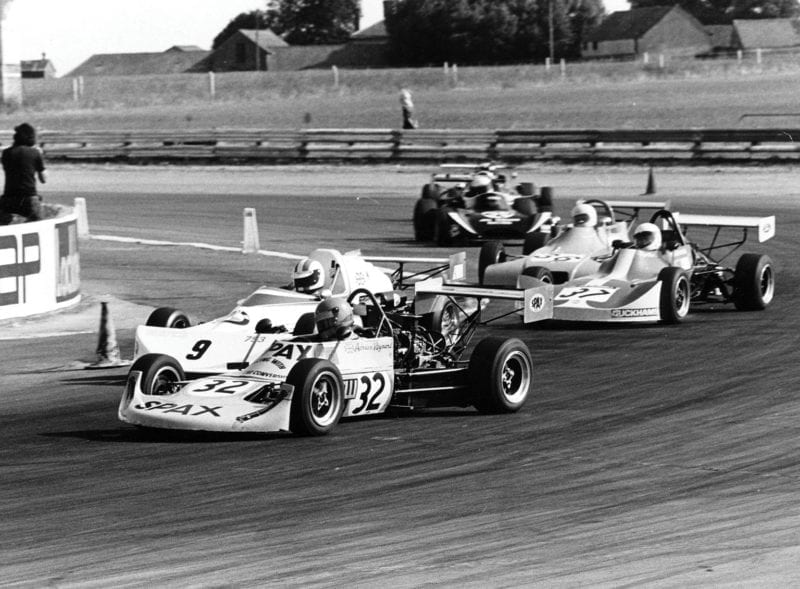

Formula Ford action at Silverstone in 1974

Motorsport Images

“Bill steered me towards Formula Ford, so I bought a Ginetta G18B for £600 including trailer. But when an accident at Brands Hatch bent the chassis I rebuilt it and sold it, reasoning that it’d be cheaper to build my own car. My final-year college project was meant to be a lateral strain gauge accelerometer, but instead I built up my car in the apprentice school at British Leyland. I told them it was a Formula 3, because I didn’t think BL would approve of something with Ford in its name! I presented the first Reynard car at the Poly to much acclaim, but of course I got zero marks because it wasn’t what I’d been instructed to make.”

In February 1973 Bill Stone decided to leave March and set up his own company manufacturing racing car components. And he approached the still 21-year-old student to come in with him. “I couldn’t believe my good fortune. It’s one of the best things that ever happened in my life. Here was this brilliantly talented engineer, an ex-racer who knew everybody in the business, wanting to go into partnership with me. We called the firm Sabre — for Stone, Adrian, Bill, Reynard and Engineering — and Bill was initially the sole employee because I had to continue with my BL sandwich course. He found an ex-undertakers’ shed in Bicester, with the coffin-making machine still sitting there, and Sabre started doing fabrication work.”

Adrian’s self-built car, the Reynard 73F, had its first outing at a nonchampionship Silverstone race late in 1973. And it won. This was the start of a remarkable Reynard tradition that translated to FF2000, Formula 3, Formula 3000, Indycar and even to sports cars: in its first race in a new formula, a Reynard has always taken victory. It’s a unique record.

During 1974 Adrian raced his Formula Ford until the money ran out, whereupon he passed the car on to his friend Jeremy Rossiter. His apprenticeship finished, he did a year in BL’s Prototype and Build Development department, and then enrolled on an MSc course in Vehicle Dynamics at Cranfield. For 1975 he updated his FF design for the new Formula Ford 2000, with shovel nose and side radiators, and Rossiter persuaded his employers, Spax Shock Absorbers, to sponsor a two-car team for them both. Meanwhile Adrian got to know Rupert Keegan, who was earning a reputation as a fast but wild Formula Ford driver, backed by his father Mike, the wealthy boss of British Air Ferries. When Mike Keegan bought a controlling share in Hawke, he decided that Rupert, and Hawke, should have a Formula 1 car, and reckoned that young Reynard was the man to design it. “Sabre still couldn’t afford to employ me full-time and it sounded like an interesting opportunity. So I left Cranfield without completing my Masters.” But Adrian got the letters after his name in the end: some 20 years later Cranfield awarded him a Professorship, and Oxford Brookes gave him their first Honorary Fellowship.

The same venue, one year later, with Adrian now in FF2000

Motorsport Images

“I started laying out the Fl car — a pretty standard DFV/Hewland set-up — but Rupert was now leading the F3 championship in an old March. Fortunately Mike decided that the Fl should go on the back burner, and told me to design a monocoque F3 car, quickly. After weeks of 18-hour days it was ready for Brian Henton to test. It was as quick as the March but no quicker, so Mike bought a Chevron for Rupert, my car was set aside and Mike fired me. He also fired one of his British Air Ferries air hostesses, a girl called Gill, because I’d taken her on holiday when she was meant to be working. She became Mrs Reynard.”

In 1978 Bill decided to return to New Zealand and Adrian became Sabre’s sole owner. That season he scored his first FF2000 win, and in 1979, while David Leslie dominated FF2000 in the UK in his Reynard, Adrian tackled the European Championship. He was victorious at Zandvoort, Jyllandsring and Nivelles and won the series. “I still entertained ambitions of becoming a full-time racing driver, but the next rung on the ladder would have been F3. I was already 28, and I had to accept that it was too big a step for me. So I made a conscious decision: from now on my career had to be as designer, engineer and businessman.

“As well as our own cars — in 1979 we’d sold our 70th chassis — we were making parts for March, Royale, Van Diemen, Chevron and others, and we had 12 employees. It was impossible to stay in the tiny coffin works, which cost us just £39 a month in rent. I took on a new 7500 sq ft factory in Telford Road, Bicester, and to do it I had to take out a £90,000 bank loan. That’s the trouble with young companies: they can’t grow gradually, they have to go through step-changes. We had a good reputation now in FF2000, but the trouble was, the 1980 car was a dog. It understeered in the corners and was a brick down the straights. I’d always been fascinated by aerodynamics, but at that stage I’d never ventured inside a wind tunnel. I designed a car based on what other successful cars looked like, but you can’t take individual elements and transpose them onto another car without understanding the thinking behind it. It was a big mistake, and I’ve never since looked at another car to copy it. It was a difficult time. I had to sell everything I had and put the staff on a twoday week. Frank Bradley, whose main business was jellied eels, blamed me because his car was uncompetitive. I couldn’t give him his money back, so to keep him happy we made him hundreds of whelk pots instead. For 1981 we updated the old ’79 car and just broke even making parts, from oil tanks to quick-lift jacks.

“In 1980 I did some work in Formula 1, engineering the RAM Williams that John Macdonald was running for Rupert Keegan. Rupert was having trouble qualifying, but we made a few changes, and at Watkins Glen he qualified 15th — ahead of Villeneuve and Scheckter in the Ferraris! — and finished ninth. Then in 1981 the works Marches were failing to qualify, so I was called in to help. The car was never exactly going to be a leading contender, but we improved it a bit, and Derek Daly was seventh in the British GP after a pitstop. For 1982 March hired me as chief engineer on the Fl team, and my fees helped keep Sabre alive. I’d put in a manager, Ivan Deacon, to run things day to day and March was only a two-minute walk from our factory.”

Preparing for his maiden FFord race at Silverstone in 1973

Motorsport Images

The 1982 Fl March, with a lot of input over the winter from Adrian, was much better, and lighter, than the 1981 car. But Jochen Mass and Raul Boesel both had a miserable season, and relations between Adrian and John Macdonald became strained. Then Colin Chapman summoned Adrian to Ketteringham Hall to discuss a job at Team Lotus. “I remember sitting at a big boardroom table, with the great Colin Chapman the other side grilling me, and I was so nervous I left big sweaty hand-prints on the polished mahogany. Chapman told me he demanded 110 per cent, and I’d have to give up Sabre if I joined him. I said I was sure I could give him what he wanted, but I couldn’t give up Sabre, and that was that. Perhaps I wouldn’t have got the job anyway — it went to Nigel Stroud — but no regrets, it was the right decision for me. And three months later Chapman was dead.”

By now the general economic climate was improving and, having had some proper wind tunnel experience at MIRA for March, Adrian designed a very slippery new FF Reynard, with inboard suspension and side radiators. James Weaver put the prototype on pole at the Formula Ford Festival in late 1981 and finished third. In 1982 45 cars were sold, including 15 to the United Arab Emirates. A driving force behind this success was new employee Rick Gorne, who’d been a successful Reynard racer in FF2000 and then had a big Formula Atlantic accident that ended his cockpit career.

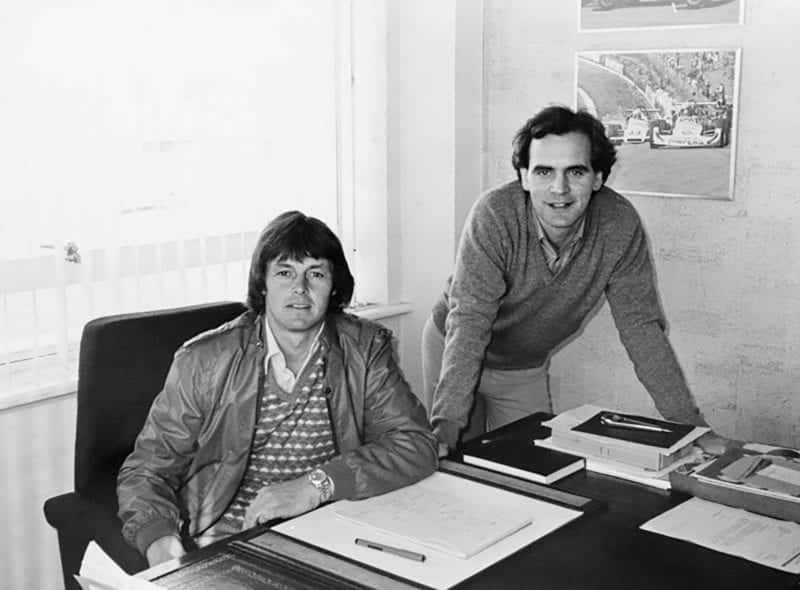

“As fellow racers, Rick and I had had some major altercations on the track, shaking fists, rows in the paddock. Then I began to appreciate his enthusiasm and his charm. But I had to work hard to persuade him to join me. He said he’d only come if I focused entirely on my job, designing racing cars. The deal was that I would make them and he would sell them. And he became the most successful racing car salesman ever. I’d cringe at some of the deals he’d do, because it might involve getting the best driver into one of our cars regardless of profit, but it worked brilliantly. He’d go anywhere to root out a prospect, and once he had a lead he’d never let go: he’d pester them, entertain them, convince them. It was easy for him, because he really believed in the product.”

Reynard was now selling a lot of cars and winning a lot of races. And in racing you always look for the unfair advantage. “The rules said the car had to race above the minimum weight limit, but they said nothing about practice. So for 1983 we built an ultra-light FF2000 car for Tim Davies, and he’d go out to qualify 60 to 80 pounds underweight, which on most UK circuits translates to 0.5 to 0.8sec a lap. He’d get pole position by a big margin, completely demoralising the opposition. Then we’d add

ballast before the race so he was legal. In the race he was on equal terms, but psychologically the others were beaten already.” The same year Maurizio Sandro Sala, having been persuaded to switch from Van Diemen to Reynard, won the Esso FF Championship, while in the FF Festival the Reynards of Andrew Gilbert-Scott and Andy Wallace finished first and second.

In 1984 Reynard sold more than 170 cars. Paul Owens, ex-Chevron, joined from the ATS Fl team: “Paul brought us carbon-fibre experience and his contribution was fantastic. Up to then carbon-fibre had only really been used in the upper formulae, but for 1985 I wanted to build a carbon F3 car and got an £80,000 government grant to do it. We bought a load of 2kW cooker elements and built an oven.” And of course Reynard’s first F3 car, driven by Andy Wallace, won its first race. It went on to break Ralt’s stranglehold on Formula 3, although by the end of the season Ron Tauranac’s cars were back on top. But in 1986 Wallace dominated F3, while Bertrand Gachot and Mark Blundell ruled FF2000. And now Reynard had a key new designer.

“A young chap called Malcolm Oastler sent me the best CV I’d ever seen. These days you’re only meant to do two-page CVs, but Malcolm’s was reams and when I read it I thought, ‘I’ve got to get this guy’. He’d raced and won in Formula Ford in Australia, he’d built his own stuff, he’d engineered everything from minibikes to buses. I’d delegate my ideas to him and he’d take them further and improve on them. A very fine engineer, and so down to earth. For 1987 he designed probably the finest FF1600 we ever made, in terms of stiffness, simplicity, performance and driveability.”

Chasing world records

And now came the move to Formula 3000. It was a big step: Lola, Ralt and March had the market pretty well tied up. Once again the potential rewards were big, but so were the risks. “The chassis was basically the F3 with extra fuel and extra crash protection, but the aerodynamics were completely different because of the bigger tyre sizes. Malcolm and I did the wind-tunnel testing together.” So to the opening F3000 of 1988 at Jerez: the Eddie Jordan-entered Reynard started from pole and won. There was yet another maiden victory. During the season, as other teams switched cars, a total of 22 F3000 chassis were sold. Herbert, Martin Donnelly and Roberto Moreno won rounds for Reynard, and Moreno’s five victories made him clear champion. Meanwhile JJ Lehto’s Reynard 883-Toyota won the British F3 title and the British Class B, European and German F3 titles were all won by Reynards.

In 1989 Oastler came up with a totally revised F3000 car. Reynard sold 36 and Jean Alesi, driving for Eddie Jordan, won the title despite moving into Fl mid-season with Tyrrell. Every round of the British F3000 series was won by a Reynard. In 1991 Reynard swept the F3000 Championship, winning nine of the 10 rounds, and by now profits were soaring.

“It was 1983 before I bought my first new car, a Golf GTi. Until then I’d been running around in £300 shitboxes. Now Gill and I had moved with our kids into Hailey Manor, a listed 18th century house with eight acres and two cottages. I was seriously into aircraft, too. I got myself a Cherokee, then a helicopter, and I bought a Spitfire, plus the remains of another Spitfire as a box of bits I was going to rebuild. I also had a WWII Harvard fighter/trainer: that caught fire in mid-air and I had to crash-land it in a field, but my passenger and I got out OK. So a lot was happening. As a company we were trying to keep our feet on the ground, investing in new technologies, looking after our customers, and hiring talented young people.

“Because I was an apprentice myself, I believe that apprenticeships are vitally important, and I’ve always tried to give as much opportunity as I can to young people. I used to get 250 letters a year from youngsters wanting a job, and we usually hired about 10 of them a year. I interviewed all the likely sounding ones myself. Rocky, Guillaume Rocquelin, who’s Sebastian Vettel’s race engineer at Red Bull, was one of my apprentices. There are several people high up in Fl now who started with me. One Australian lad was really persistent, but had no qualifications and I had to tell him we couldn’t take him. He kept phoning from Australia and in the end I told my secretary not to put him through any more. A week or so later she said, ‘It’s that Australian boy again.’ I said, ‘I told you, I can’t speak to him.’ She said, ‘But he’s sitting in reception.’ So I saw him, and I hired him. He turned out to be really good.”

With fellow former racer Rick Gorne, the sales dynamo behind Reynard’s expansion in the 1980s

Motorsport Images

In 1989 March was in trouble, and Adrian, in concert with American team owner and race car dealer Carl Haas, came very near to buying the firm that he’d first seen as a student 18 years before. “I thought it would provide a short-cut into Indycar, and it got to the point where I’d agreed to buy March Engineering for an initial payment of £1 million. But when my accountants really got into the books it didn’t smell quite right, so I walked away.

“Next, we made a serious effort to get into Formula 1. We were making annual profits of more than £1 million, which seemed a lot in those days, and I thought, ‘Well, the product’s not that different. I’ll put two years’ profit into an Fl project and the rest will happen, just like everything else has happened’. So I put together a team of really good people like Rory Byrne, Pat Symonds and Dave Wass, and we designed an Fl car. We did all our wind tunnel testing at Imperial College and devised what was then a unique shape with a high nose, to get better flow under the car. I designed a factory and, using my own money, bought the land. It was all looking pretty good. But I couldn’t get an engine deal. In the end I had to give it up.

“By the time I pulled the plug on the Fl project I was personally almost £3 million in debt. It was time to regroup and survive. I managed to sell the 15 acres I’d bought at Enstone for the factory, plus the designs for the building, to Tom Walkinshaw, and Benetton [now Lotus] is still there. Most of the personnel, from Rory down, went to Benetton. I sold the design drawings and the wind tunnel model to Ligier. I sold everything I possibly could, planes, helicopters, the lot. I had to sell Hailey Manor, and our family of six moved to a three-bedroom rental with no carpets next to Toys R Us in Oxford. It was tough on Gill, but she kind of liked the simplicity of it, taking the washing down to the local laundrette. As for the company, although I lost Rory and the other Fl guys, I still had the core team. I felt we would eventually dig ourselves out.”

The prime route to achieve that was Indycar. “In 1992 I spent a lot of time in the USA engineering Russell Spence’s Formula Atlantic car, and it was a perfect way to spy out the land. I tried very hard to get in with Carl Haas, but he was entrenched with Lola. Then I came across Chip Ganassi, a former Indy racer and team owner who was looking for further success. I’m still not sure why Chip made the ballsy leap of faith to go with us, because we had no record in Indycar. But he agreed to invest in Reynard North America, which we based at Indianapolis, and he ordered 12 cars for 1994. In fact we’d sold 13 by the end of April. Malcolm was chief designer, assisted by Bruce Ashmore who’d moved across from Lola, where he’d been chief designer on their Indycar chassis and also Mario Andretti’s engineer.”

Jean Alesi won the 1989 F300 title in a EJR 89D

Motorsport Images/Sutton

It was a season dominated by the Ilmor/ Mercedes-powered Penskes. Yet once again Reynard scored a story-book maiden victory, when Michael Andretti won the opening round at Surfers Paradise. In the Indy 500 Jacques Villeneuve, in only his fourth Indycar race, finished second and took Rookie of the Year. And in 1995 Villeneuve won the Indy 500, and the championship. With 15 cars on the grids, Reynard easily won the Manufacturers’ Cup. It was the same story in 1996, with Jimmy Vasser champion in his Chip Ganassi Reynard. In the USA Reynard ruled, now more profitable than ever before. And once again F1 raised its head.

“We’d obviously built up a good relationship with Jacques Villeneuve, and his manager Craig Pollock was talking about moving into F1. That was superseded by Jacques’ move to Williams and his World Championship, but Jacques and Craig had an appetite to do more. Then Craig was able to get the car of British American Tobacco, and the plot was hatched: BAT would provide the money and Jacques would be No 1. Renault were keen because Jacques had already got them a world title. And the car would be called a Reynard.

“But soon, far from being the dream team, it became clear that we were required to put in a considerable amount of money. And Renault dissipated its interest by becoming involved in Flavio Briatore’s Supertec operation, and everything was delayed by a year. Then it emerged that the car would be called not a Reynard but a BAR, which wasn’t a brand that anyone could relate to. Finally BAT insisted that, rather than using the available funds to start a fledgling team as Jackie Stewart had done, we had to buy Tyrrell.”

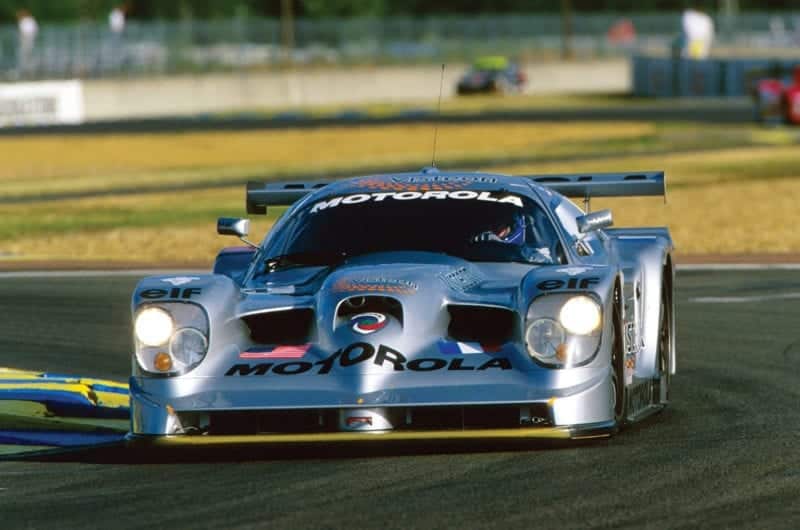

Panoz GT benefited from Reynard’s input

Motorsport Images

BAR was a horribly public disaster. In its first season, 1999, the team posted 24 retirements out of 32 starts, and scored not a single point. In 2000 there was some improvement, and equal fourth place in the Constructors’ Championship, but in its entire four-season existence BAR scored but one podium, Villeneuve’s third at Hockenheim in 2001. “There were other demotivating things. I found it hard to work with Craig and I disagreed with a lot of budgetary decisions. I passed most of the design responsibility over to Malcolm and, although he’s a fantastic intuitive engineer, you need to be tough to cope with the politics in Fl, and Malcolm’s one of the nice guys. The Honda engine we had for 2000 was meant to have 800bhp, but actually it wasn’t any better than the Supertec, and it was rather heavy. At the end of the day none of it was good enough. Craig and I weren’t gelling and I resigned as technical director, although I was still actually a shareholder when it all folded.

“By now all our focus at Reynard was on the USA. We’d been very successful in Indycar, we were doing the Barber Dodge cars and the Chrysler touring car programme, and work for some major manufacturers. My main challenge in terms resources, staffing, factories and development was how to keep on growing. I brought in Alex Hawkridge, former Toleman Motorsport managing director, as CEO with the aim of turning Reynard public, and we spent a lot of money reconfiguring the company. To keep our expansion process going, we invested $10 million in buying the American race-car maker Riley & Scott.

“In August 2001 I made the decision to lay down 50 Indycars. In the previous three years our sales had been running at that level and we knew all the teams, we knew what their needs were going to be. Then on September 11, 2001 I was coming out of a BAT board meeting when I heard what had just happened in New York and Washington. I realised the huge significance of it all, but I’d been through crises before. I knew the series, I knew the teams, I knew the sponsors. I made the decision to carry on.

Johnny Herbert gave the Reynard 88D a victorious debut at Jerez

Motorsport Images

“On November 3, when we arranged to deliver our first 2002 car, the customer didn’t want to take it. That was a surprise. Soon we had four cars sitting on the shop floor and nobody had paid for them. The dot.com bubble had burst, the US stock market was shrinking, everything was going soft. I’m not saying it was all down to Nine-Eleven, but it would have helped if we’d been able to deliver those cars at the agreed prices. We realised that the race car manufacturing world was shrinking, and we started down-sizing as fast as we could, keeping our core competencies but economising on functions we could do without. Soon, from 375 staff, we were down to about 160. By February we were distress-selling the cars we had, because we were running out of cash. I tried everybody I could think of to put some money into the company, but in the end I had to accept there was no way forward. We were bust. Everything we’d worked for over 29 years: it had all gone.

“The liquidator put everything up for sale, but I couldn’t bear to go to the auction. There were no takers for the company, which a year or so before was going to be valued at £100 million. A few bits and pieces sold, tools, metal in the racks. Zytek bought some sports car drawings, Derrick Walker bought some Indycar drawings. I had to decide what to do next.

Hitting the heights Stateside with Jacques Villeneuve

Motorsport Images

“I did inherit the Auto Research Center, which was effectively a wind tunnel in a shed in Indianapolis with eight staff. It was owned 10 per cent by Honda, 31 per cent by [team owner] Bruce McCaw and 59 per cent by me, because I’d loaned Reynard Motorsport the money against those shares. Over the past 10 years I’ve built it up, doing work for major road car manufacturers. They have to achieve 54.5mpg by 2015 to meet the US government’s CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) targets, and they’re using our aerodynamic expertise. Concentrating on the underneath of the car and the rotating masses, we’re finding an 8 per cent fuel saving, which equates to about 3mpg. Trucks too: we’re now the biggest truck aerodynamicists in the US. We’re up to 50 people. We’ve added an extra 35,000 sq ft to the original building and we have another facility in North Carolina.”

BAR F1 briefing with Craig Pollock (left) and Malcolm Oaster

Motorsport Images/Sutton

There have been many other Reynard projects. The Panoz GTR-1 was designed by Adrian in answer to Don Panoz’s ambition to build a modern sports-racer with a big American V8 in the front, and good weight distribution. The Reynard 2KQ was a VWengined Le Mans car that, remarkably, won the LMP675 class at Le Mans three years running, finishing fifth overall in 2001. There was the Patriot turbine-electric hybrid sports-racer developed with Chrysler in 1993; the Chrysler Stratus touring car racer; the Ford Indigo sports car. And, just recently, the Reynard Inverter.

“Just for fun, I decided to do a sports-racer with a motorcycle engine, complying with the 750 Motor Club’s Bike Sports formula. The first one we made, with a 1000cc Honda engine, had so much grip that everywhere was just flat, which wasn’t very entertaining. So the second one has a Suzuki Hayabusa, and more grunt. I got my competition licence back and did three races last year, had a win at Brands in the wet and pole at Donington. I’m going to do all 12 races in the series this year. Everybody should take up circuit racing in their 60s!

“I don’t have any fixed-wing aircraft any more, but I do have two helicopters, both Robinson 44s. And I was the first person to sign up for Virgin Galactic.” This is Richard Branson’s scheme to take paying passengers, as soon as the technology allows, on a spacecraft flying at 2500mph, 70 miles above the earth. The trip will cost £125,000, and about 550 people have put down a deposit, including Stephen Hawking, Tom Hanks, Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt. “I’ve already done my astronaut training. They whizz you round in a frame until you sustain 9g, but because I’ve flown aerobatic aircraft they put me up to 16g. That was an incredible sensation.”

Clearly, risk still stimulates Adrian Reynard. But risk in the world of motor racing business is behind him now. ARC is thriving, but beneath Adrian’s ebullient exterior you sense that there are still scars left by what happened to the firm that carried his name, the firm which consumed his heart and soul for so long, and to the friends, colleagues and employees who lost their jobs. Better now to find thrills in a motorcyclepowered sports-racer, a helicopter or a spaceship than to return as a race-car builder to the battle of the balance sheet.