The car had flaws, though, and Stewart for one was not shy about saying so. “I have massive respect for Robin,” he says, “and the car he built was robust and clearly very fast, but it was not easy. In fact I’d say it was the most difficult F1 car I drove. The H16 BRM had all sorts of issues but was very manageable compared with the March. On jounce and rebound the 701’s responses were incredibly fragile. I think Chris and I were able to go quickly because we were probably the two smoothest drivers around at the time, so therefore did least to upset it. But I had to stretch my personal elastic much farther than I cared to get the lap times. The Tyrrell was very straightforward, even with its short wheelbase. And as for the Matra — I could have slept in that and still been competitive.”

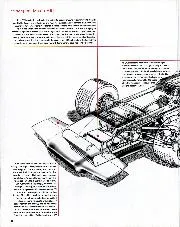

The problem was weight distribution. Herd: “We had this big, heavy radiator at the front, which I balanced by putting the big, heavy oil tank at the back. But having these masses at either end gave a high polar moment of inertia that made it unpleasant to drive, although the problem was mainly in slower corners.”

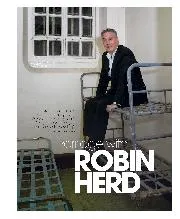

Herd admits there was a more fundamental issue, too: “Because the car was so simple, it didn’t leave much room for development. While our rivals got quicker throughout the season, we stood still.”

If you look at 701-2 in close detail, you’ll see all sorts of unique Tyrrell modifications, including adjustable front aerofoils, a steering damper and different pick-up points for the rear suspension.

The engine is warm now. It’s a strong DFV built to modern regulations, if not to the ultimate specification, but it still gives better than 500bhp at a very safe 10,500rpm, compared to the 430bhp it would have had when new. In a car weighing little more than half a tonne I am under no illusions about what is about to be unleashed.

I’d feared the cockpit would be so small as to deny me access, but the only real problem is that the top of the surround is too narrow to accommodate my shoulders. Happily this can be detached with the loss of only the headrest and some purity of line. As a car designed mainly for customers, I guess Herd knew it had to be able to take a wide range of physiques.

Clearly no efforts have been made to vary the driving environment from the norm of the day. A simple central tacho is flanked by combination dials providing the temperatures of water and oil, plus oil and fuel pressures. Everything is in slightly the wrong place — the gearlever too far back, the elbow slots cut into the body sides too far forward, which says nothing about Herd’s interior design and everything about the difference in forearm length between Jackie and I.

Frankel climbs in

Stuart Collins

The DFV blasts into life. There’s never much theatre with such motors: no little coughs, splutters, bangs or rasps to build expectation before f treating you to the full choral magnificence of its voice. This is a DFV, the Mike Tyson of racing engines: not nice, not pretty, but capable of hitting harder than anything else of its era.

That said, a modern DFV is far easier to manage than those of 10 or 20 years ago, which could be made to give more than 500bhp but only with that power concentrated into a tiny band somewhere between 8500-11,500rpm. They don’t exactly run like road car engines even now, this one requiring a steady foot and 3000rpm just to maintain an uneven idle, but it’s tractable enough to pull out of the pits and onto the track without making you look like the out-of-depth amateur you really are. Donington Park’s wide open spaces, smooth surface, quick corners and long straights are the perfect place for this.