Earlier Jimmy had won the saloon car race in a works Lotus Cortina, and his hat-trick came with victory in the GT event, at the wheel of Ian Walker’s Elan. Just another day in the life of a World Champion, but one I have never forgotten, not least because it defined for me how a great man can behave.

It is no more than inevitable that so many of my Lotus memories should be wedded to Jim Clark. I saw him win the Aintree 200 in 1962 in the revolutionary Lotus 25, and watched him finish third in the same race a year later after taking over the car of Trevor Taylor (the last time, I believe, a car changed hands in an F1 race), making up half a minute on Graham Hill’s winning BRM, and setting a lap record which was to stand for all time.

I was there, too, at Silverstone in 1965 when Jimmy won the British Grand Prix, coasting through Woodcote in the late laps, trying to save an engine with disappearing oil pressure. Two years later, now in the Cosworth-powered 49, he won again, this time without problem.

A while ago I saw in an auction somewhere a handwritten letter from Clark to Andrew Ferguson, the Lotus team manager, in that summer of ’67. Jimmy had taken to commuting from Paris (where he was spending a year in tax exile) to the European races in his yellow Elan, and the car – surprise! – was not without its foibles, which its owner detailed at some length. Then there was a PS, asking Ferguson if he’d give The Green Man a ring, to see if a room could be found for him over the British Grand Prix weekend. As I said, another world.

It was to be the last time Clark raced in Britain – indeed the last day on which he set foot in the land – for his tax exile status allowed only a handful of days here, and ended ironically the very week of his death, at Hockenheim the following spring.

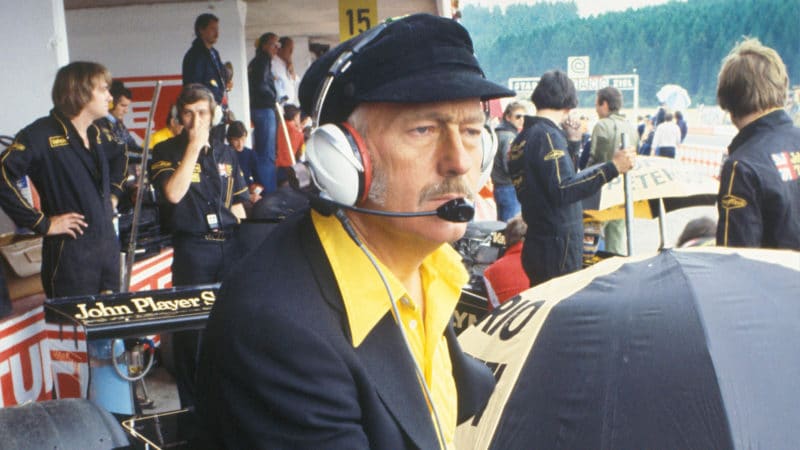

Chapman struggled to get over loss of Clark

Getty Images

A decade later, it was still difficult for Chapman to accept his loss. “For me,” he said, “Jimmy will always be the best. In time someone else will come along, and everyone’ll hail him as the greatest. But not me. Once or twice Jimmy came close to retiring, and I had mixed feelings: the idea of racing without him was almost unthinkable, but at the same time I desperately didn’t want him to hurt himself.”

This was a side of Chapman I had never seen before, nor ever would again. We were in his office at Ketteringham Hall, and at one point he almost broke down. When his secretary brought in tea he turned away, pretending to look for something. “Jimmy had more effect on me than anyone else I’ve known,” he said. “Racing changed for me after 1968.”

That may have been so, but the desire for success remained. That same year Graham Hill won the World Championship in a Lotus, and for 1969 he was joined in the team by Jochen Rindt, a driver with whom Chapman had many a spat, but one whose genius he found irresistible.

I have written before of the ’69 British Grand Prix, of the race-long scrap between Rindt’s Lotus 49 and Jackie Stewart’s Matra, but another race at Silverstone that year – the Daily Express International Trophy – made as great an impression on me.

Team Lotus did not so much as arrive for Friday practice, and the following day there was rain. Finally it stopped, and on a still slippery track Rindt went out to try and salvage something: through the old Woodcote he was travelling at a different sort of speed from anyone else, and somehow turned in a lap good for the third row of the grid.