Lunch with... Frank Gardner

The colourful Australian remembers his time spent racing and engineering a variety of cars in Europe during the 1960s and ’70s

John Downs

Frank Gardner doesn’t believe in giving interviews, particularly if they involve looking back on his eventful and versatile motor racing career. “If you look over your shoulder,” he says dismissively, “all you get is a bloody pain in the neck.” Before I called him I don’t think we’d spoken since he scored his final race victory in England more than 30 years ago, at Silverstone in September 1974. But for old times’ sake – and because “I see your stuff sometimes and maybe it’s not quite so full of bollocks as the rest of them” – he agreed to have lunch with me at his local golf club (above), half a mile from the beautiful house he has built on the edge of a lake close to the Queensland coast.

Frank’s 30 years in racing started and finished in his native Australia, but for more than half of them he was based in England. Through the 1960s and early ’70s he was a familiar sight at major European events, folding his rangy frame into a Formula 5000 cockpit or a long-distance sports-racer, or walking pensively down the pits on the balls of his feet like the boxer he once was, that little white towelling hat on his head, quietly sizing up the opposition and thinking through his strategy. He is remembered not only as a hard, uncompromising racer but also as a brilliant hands-on engineer, able to develop the race-winning potential of almost any car. And he’s also remembered for his colourful off-the-cuff descriptions of racing incidents and racing people, most of them unprintable even now.

He plays down the technical input he had into the cars he drove to race wins and titles – “the good cars always had good blokes behind them” – but then he likes to play down the wins and the titles too. About his own accomplishments he is modest, and he has a keen nose for pretentiousness in others. He calls it his bullshit filter. He is not a man to suffer fools, and he tends to call a spade a bloody shovel.

Frank was born in 1931, the son of a New South Wales fisherman. “One night coming home from the boats he was hit by a car, so that was his lot. I was 12 years old and I didn’t have a home to go to any more, so I went to live with my uncle.” That uncle happened to be Hope Bartlett, a 1930s name in Australian racing in Vauxhall, Grand Prix Sunbeam and Bugatti. In 1949, aged 17, Frank borrowed an elderly MG TA from his uncle to do a race at Marston Park. “Just oil drums round an old airfield, watched by seven people, two kangaroos and a porcupine. I made sure I washed and polished the MG and did the tappets before I gave it back.” He forgets to mention that he won the race.

“I was serving my time as a mechanic, and on weekends I worked on my uncle’s buses [Bartlett had a thriving bus company]. I raced motorbikes, speedway stuff, but I also did a lot of swimming, surfing, diving, rowing, sailing.” It was all developing Frank’s fiercely competitive streak. He wanted his own garage business, but he had no money to set it up. So, having been a useful amateur boxer, he turned pro for a while because it was the quickest way he could think of to get some cash. “It wasn’t a very nice environment, boxing. It was all very underworld. But none of my fights ever lasted more than four rounds. And it got me the substance to get the garage started.” This was Whale Beach Service Station at Avalon, north of Sydney.

F1 in 1965 with John Willment’s Brabham-BRM

Motorsport Images

In 1953 Hope, now in his sixties, bought a Jaguar XK120 road car and used it to win a production car race at Bathurst. Then Frank bought it off him – “they were only worth about £800 in those days” – and set about turning it into a competitive racer. “It was way too heavy for serious racing, so I made a fibreglass body with a forward-hinging one-piece front end, just took plaster moulds off the original body to do it. I cut and shut the chassis, and sorted out the brakes, drilled the drums and wheels to let the heat out. Wherever I put that XK on the grid it won, not because I could drive the bloody thing but because nobody really looked at things seriously then.”

The next step up from an XK120 was a C-type, but Frank had no hope of affording one – until he came across the total wreck of XKC 037. “The owner, a Sydney guy called Dr John Boorman, hit a Ford Customline, killed the occupants, and ended up down a ravine. I bought the remains from the insurance company and wrote to Jaguar asking for information so I could rebuild it. I thought, they’ll never answer my letter, but a few weeks later a big package arrived with all the drawings. So I had the correct dimensions, I knew which way to go and we got it all sorted out. I did it right because a proper C-type meant something even then, and I thought if I bastardise this thing it will be like cleaning up a bloody Rembrandt with after-shave lotion. But I couldn’t get it to run cool enough on some circuits, so I altered the radiator grille a bit. In hindsight I could have solved that problem, but I didn’t have the knowledge then.

“I bought a D-type after that, also crashed. Do me a favour, I couldn’t afford a straight one. This had run up the arse of a truck. The steering wheel had gone through the head rest. We rebuilt that all properly as well.” Between them the C-type and D-type, XKD520, brought Frank 25 wins out of 26 starts, taking the New South Wales Sports Car title two years running.

“Then I thought I’d go to Europe. I reckoned on five years to see what it was all about over there. So I sold a five-year lease on the garage, went across as a tourist, and ended up with a job as a mechanic in the race shop at Aston Martin at Feltham. Reg Parnell was the racing manager and John Wyer was the Alfred Neubauer. The rates of pay were such that non-smokers only need apply – you couldn’t afford any luxuries – but there were some characters there. I remember one of the fitters, a big bloke called John with a stomach on him, he liked to have 10 minutes’ kip after lunch. That wasn’t allowed, of course, so he’d sleep standing up. He’d push the front of his overalls in the vice on the bench and tighten it up, so he wouldn’t fall on his arse on the concrete floor.

“I did the Aston bit for just over a year, working on the sports-racers and the Formula 1 cars and going round all the European tracks. The year Astons were 1-2 at Le Mans, 1959, I was there. I wanted to race but I couldn’t afford to. But you have to make your own opportunities, and mine came from Jim Russell, who wanted somebody to straighten up the cars his pupils had bent at his Racing Drivers’ School up at Snetterton. So in 1961 I went to Norfolk and mended his wrecks, learned a fair bit about Lotus technology as it was then, and Jim would let me have a race in the cars I’d straightened, because if they’d just had a win they’d be easier to sell.” Frank’s first season outside Australia, and his first in single-seaters, netted six wins in the Russell school Formula Juniors, and taught him most of the British tracks. Then a fellow Australian, whom Frank had first met more than 10 years before, got in touch.

“I’d known Jack Brabham since the speedway tracks around Sydney in the late 1940s – back then he was on four wheels with his midget, and I was on two. Now Jack was setting up Motor Racing Developments, and they needed to get the first cars built.” Frank worked during the week building the chassis with another Australian, Peter Wilkins, who was later responsible for the Eagle F1 cars. At weekends Frank raced the works Formula Junior, always running at or near the front. Then came a call to partner David Hobbs in a Lotus Elite at Le Mans. They finished a remarkable eighth overall, winning the Index of Thermal Efficiency.

During the season Frank’s Brabham grew a pair of small dart-shaped deflectors each side of the nose. This was five years or more before wings arrived on the Formula 1 scene. “I found they gave me more grip at the front, and I reckoned they were worth about three-tenths a lap. But the scrutineers didn’t like them, they didn’t want me to run them, and I figured it wasn’t worth the grief of buggerising around with officialdom.” But he was to try them again on his Willment F2 Brabham in 1964.

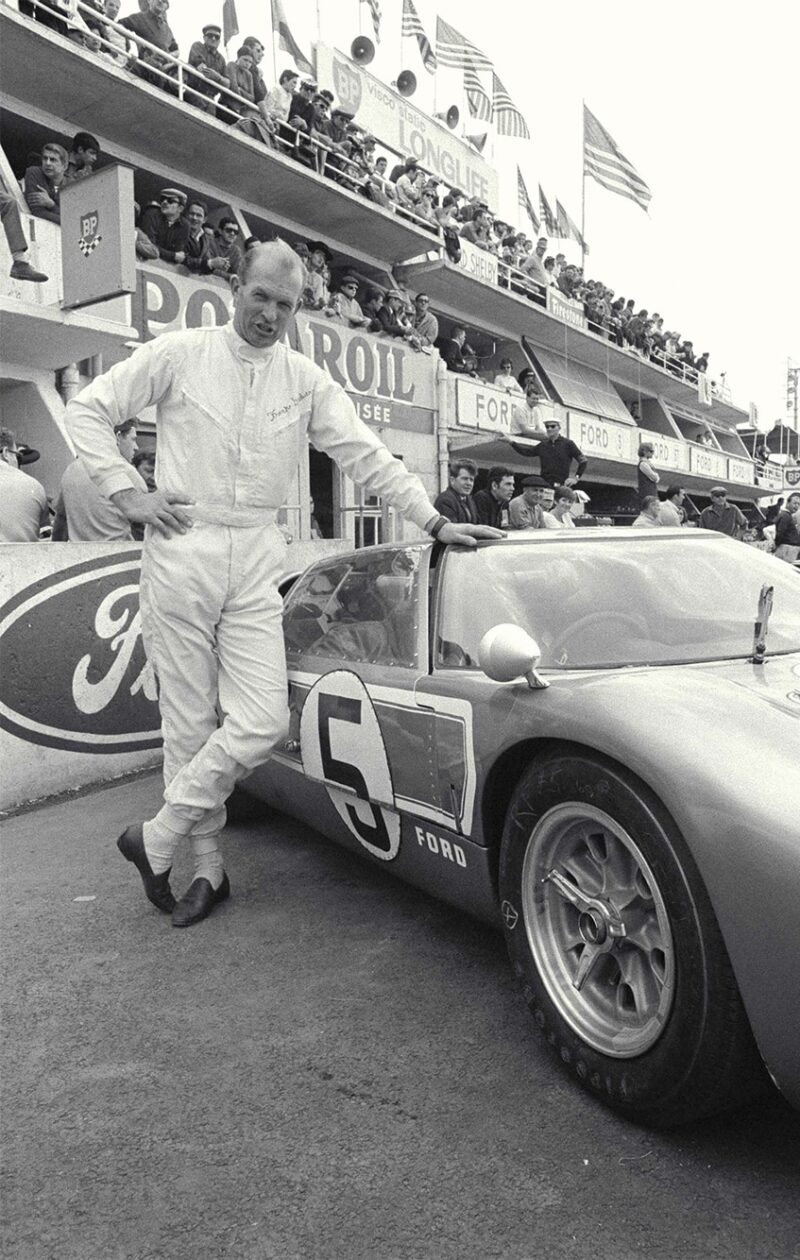

Frank drove a 7-litre Ford MkII at Le Mans in 1967

Motorsport Images

“At Brabham Ron Tauranac made really safe chassis, you couldn’t fault them, not like Lotus. I used to go crook about [Colin] Chapman because some of his stuff was dangerous. But with all single-seaters then, you had your petrol tanks each side of you. If you needed an extra tank it went behind the dash, over the family jewels. If you hit anything you were likely to be attending your own bloody barbecue.

“We had our ups and downs with Ron. Peter and I were working on a new chassis at one o’clock in the morning, we’d just got to the point where we were ready to lower the engine in. But Ron had triangulated the chassis where the engine was meant to go, and of course we couldn’t get it in. After a 20-hour day it didn’t seem so funny. So when Ron comes to work next morning Pete locks him out. Ron’s banging on the door shouting, ‘’Ere, I can’t get in.’ ‘That’s right,’ says Pete through the door, ‘we’ve locked you out. We’ve worked all night on your bloody chassis, and now we’ve got to throw it all away because we can’t get the bloody engine in. It’s not going to be much of a racing car unless we weld on a couple of shafts and get a bloody Chinaman to pull it.’

“Jack was away in America at the time, and when he came back he had to organise a treaty between us. It was just boys working too hard and doing too much, and Jack wanting the world when we could only give him half of it.

“Another time it was Ron and Jack who weren’t speaking, and I had to be the go-between. Go and tell Ron that, now you tell Jack this. Ron lives in Sydney now, and we meet up for a coffee now and again. As an engineer, the wins he and Jack put on the board, and the World Championships, it was remarkable. Not bad for a couple of bush boys.”

Over the winter of 1962/3 Frank began a pattern that he was to follow each year, returning home to race in the Australasian season. Alec Mildren signed him to drive his Brabham single-seater and Lotus 23 sports-racer, and he won at Longford and Lakeside and scored several good places. He also drove the ex-Moss/Rob Walker Tasman Cooper at Sandown. “I was full chat on the straight and when I hit the brakes something flew off the front of the car and whizzed past my head. It was a chunk of the front right-hand brake disc. The back brakes slowed me a bit, but I had to spin it so I could hit the sleepers arse first.”

Back in England, Frank joined the team of FJ Brabhams run by Ian Walker, “a very professional bloke who got off his arse and did a good job.” Frank prepared the cars as well as racing them. He also built up the Brabham BT5, a Ford twin-cam sports car to challenge the Lotus 23, and drove this for Walker as well. His team-mate in the yellow Juniors was fellow Australian Paul Hawkins. “I got on with Paul all right, he was a good practical bloke and you couldn’t wear him out, although you had to tidy up the workshop after him every so often. But he was wild. At Montlhéry I was leading and he was second, and he came onto the banking too quick, looped round and came down sideways in front of me. I was looking into his cockpit. I managed to squeeze past behind him and he hit the wall below us. He was never going to die in bed.” (Hawkins was killed at Oulton Park in 1969 when his Lola T70 hit a tree.)

There were FJ wins at Montlhéry, Zandvoort, Rouen, Goodwood and Silverstone, and at Monaco Frank won his heat and was second in the final. And the little sports car was a habitual class winner, frequently humbling bigger cars. At the Oulton Park Gold Cup meeting Frank was on pole, ahead of Roy Salvadori’s big Cooper Monaco and Jimmy Clark’s Lotus 23B. “At the start of the year the BT5’s aerodynamics weren’t right, it had too much pressure at the front and not enough at the back, so the head of the dog wagged the bloody tail. But when we got that sorted it was a good little car. In that race Jimmy led but I didn’t have any trouble hanging onto him, and Jimmy Clark was certainly a better driver than Frank Gardner. I was just looking for a way to get past when Jimmy spun it, unusual for him. When a car spins in front of you the best way to avoid an accident is to aim for it, because when you get there 19 times out of 20 it won’t be there any more. But this was the one in 20, because he came back across and ended up where he’d started, so I looped it and went down the road upside down. I took the skin off my back and split my arse open on the screen. Problem was the car was due to be flown to Canada next day for Graham Hill to drive at Mosport on Saturday. So I had to rebuild it in a hurry, which was just as well, because I couldn’t sit down.”

‘Bloody awful’ Porsche 917 was wrestled to eighth in the 1969 Nurburgring 1000km

Motorsport Images

Frank got the Brabham to Mosport on time, but Hill opted for the Walker team’s Lotus 23, so Frank drove the Brabham. He was relieved when carburettor trouble put him out: “I was stuck in the bloody cockpit because my war wound had split open. But I don’t want to give you hard luck stories. If you want to tell hard luck stories, get yourself a Labrador. They’re good listeners.”

That winter, before going to Australia, Frank made the first of many racing visits to South Africa to share a Willment Cobra with Bob Olthoff. “The Cobra was sent over from England with strict instructions that it was to stay on display in the Grosvenor Motors showroom in Johannesburg until I got there. But Olthoff was a local hero, and he thought it would be a good idea if he did a few laps of the downtown speedway in front of his home crowd, and he put it into the sleepers. Bent it rather badly. So I arrived and spent the week straightening out the bloody thing, crack-testing a few things that were doubtful and making secret phone calls to England for Cobra bits, bypassing Willment to save Bob’s arse. In the race we were going well, and then with less than an hour to go Olthoff didn’t come round. He’d jumped off the road, the Cobra was upside down in the boonies and he was in the ambulance on his way to hospital. Well, I walked out there in the dark and I rustled up some locals – I told them not to smile so no one would spot us – and we heaved it back onto its wheels and I fired it up. It was the other side of a big ditch, so we pulled down some fence posts to make ramps to clear the ditch. I borrowed a crash hat from a passing motorcyclist and I drove it back around to the finish line, wheels pointing everywhere, broken windscreen, leaking and smoking and steaming, and waited for the race to finish. The David Piper/Tony Maggs Ferrari came round to win, and I chugged it across the line to finish second.”

In 1964 Frank raced John Willment’s F2 Brabham all over Europe, and in 1965 Willment optimistically decided to add Formula 1 to his sports car, GT and saloon programmes, buying the ex-Jo Siffert Brabham-BRM. In the season-opening South African GP Frank ran mid-field until he was delayed by gearbox problems. He was a rousing fourth in the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, and in the Silverstone International Trophy he was holding fifth ahead of McLaren, Bandini, Rindt and Rodriguez when the clutch exploded. But in the half-dozen GPs that followed he had little joy. The budget was tight, retirements were frequent, and when a wheel collapsed at Monza Frank decided this was not how to go F1 racing. But he was also very busy in Willment’s Lotus 30, Cobra coupé and Cortinas – occasionally beating the works cars of Clark and Sears – and he had F2 rides in Cooper and Lola too. In the Tasman Series at the start of that year he ran well in Mildren’s 2.5 Brabham-Climax, finishing second to Graham Hill in the New Zealand GP, and second to Clark at Levin and Lakeside.

F2 Brabham used Frank’s own nose wings, first tried in Formula Junior

Motorsport Images

All these results are gleaned from contemporary reports, my own memories of the races I saw, and the database compiled by British Frank Gardner fan Tim Cox, which covers almost 500 races. Frank himself is uncomfortable talking about his achievements, preferring to regale me with stories of the races that didn’t go so well. “I did the bumpy old Zeltweg airfield circuit in Austria in the Lotus 30. It was going all over the bloody place in the closing stages but I got it home third. Back in the paddock we found that the backbone chassis had broken in two. I think the bloody doors were holding it together.

“The Reims 12 Hours started at midnight and went on until noon. Doing the Le Mans run-and-jump start under the bright lights of the pits and then accelerating off into the darkness was, um, quite dangerous. I was sharing the Cobra coupé with Innes Ireland and I was waiting for my signal to come in for fuel when it spluttered to a halt miles away out on the circuit. Near where I stopped some trucks were parked with fuel churns on the back, guarded by gendarmes sitting around a fire. I relieved them of one of the churns while their backs were turned, sloshed half of it into the car and the rest all over the road, got the thing started and drove back to the pits to refuel properly. But the car was detonating like mad, and it turned out I’d filled it with some low-octane stuff, helicopter fuel probably, which meant the engine was buggered. I never did get around to writing a letter to the French thanking them for the loan of their fuel.”

It’s typical that Frank tells this story against himself and fails to mention that, a few hours later, he drove a Lola in the Reims F2 race that followed the 12 Hours. It was a classic slipstreamer, and after 93 minutes three and four abreast Frank finished a sensational second, a fifth of a second behind Jochen Rindt and a tenth ahead of Jim Clark.

There were more Lola F2 drives in 1966, but now Frank had also been signed by Ford competitions boss Walter Hayes, and this was his introduction to Alan Mann, who was then responsible for much of Ford UK’s competition involvement. “Ford’s problem was that they had Jimmy Clark winning in Cortinas, and the headlines always said Clark wins rather than Ford wins. So Walter had a word with Alan, and it grew from there.”

Frank raced Cortinas in the US on a Ford promotion programme, and his usual team-mate was Sir John Whitmore. The two of them, from very different backgrounds, shared a similar sense of humour, so it was a fruitful partnership. They also shared Alan Mann GT40s at Le Mans, Sebring and Spa. “John had a good head on his shoulders. Capable of driving anything, and not a political animal in any way. We never had a cross word.”

In 1967 Frank was racing virtually every weekend. He won the British Saloon Championship after a string of victories and lap records in the red and gold Alan Mann Ford Falcon, a four-year-old Monte Carlo Rally car which was carefully developed into an invincible circuit racer. In big sports cars he raced Mann’s GT40 and Sid Taylor’s Lola T70 and, at Le Mans, one of the works 7-litre Ford Mk IIs. “Ford attacked the thing pretty well, I can tell you, showed everybody how to spend money. They even brought their own drinking water across. They had seven 7-litre cars in the race, and most of them crashed. Luckily the two that survived were first and fourth.

“The problem was Ford had this policy that they wanted an American in every car. Fine when it was a Dan Gurney [Gurney and A J Foyt won the race], but some of them were just oval racers, and they’d never raced at night. I was with Roger McCluskey and Denny Hulme was with Lloyd Ruby. It was a shame, because if Denny and I could have shared a car we’d have strode right along. Ruby crashed Denny’s car around midnight, and then at five in the morning McCluskey walked back into the pits and said he’d had a little accident. Denny said, ‘We’re on finishing money, we may as well go and see if we can get the bloody thing running.’ So we walked down to the Esses and the first thing I saw was this radiator up in the trees. I said, ‘I don’t think there’s going to be much to share with you, Denis.’ If that was a little accident I’d hate to see Roger have a big one.”

Frank was back with Brabham, too, running a works BT23 in F2, and despite missing several rounds he was runner-up to Jacky Ickx in the European Championship. He did some F1 testing for Brabham, and did the Oulton Park Gold Cup in a year-old BT19, running third until the ignition packed up.

“I don’t regret not getting stuck into F1. In my career I did what seemed right at the time, and what mattered to me was the people I got to work with, the Eric Broadleys, the Alan Manns. Everything was always done on a handshake. If you need more than a handshake, you’re getting back to the boxing world, with bloody traders and hangers-on, everybody after a free meal. I suppose I’d have been pretty much there in F1. I drove with people like Denny and I tested with Graham, and my times were about right without me throwing it off the road. But if the Queen had balls she’d be the King, wouldn’t she?”

In 1968 Ford wanted Alan Mann to go the Escort route, and with an FVA F2 engine under the red and gold bodywork Frank won the British Saloon Championship again, with class wins this time – although in the final round, with the title already won, he lifted his self-imposed rev limit, out-qualified all the Falcons and won outright. He did some European Championship rounds, winning at Aspern and Zolder, and he also had an isolated outing in the Silverstone International Trophy in an F1 Cooper-BRM. But his highest-profile task that season was trying to sort out the dramatic Ford F3L, Mann’s Len Bailey-designed aerodynamic coupé with F1 Cosworth DFV power. This hugely ambitious project never achieved its potential.

“The coupé and the open car that followed it, the P69, were wonderful looking cars, but their aerodynamics were bad, and they were too cramped. Len Bailey pulled everything down to the last sixteenth of an inch in the cockpit, and there was hardly any elbow room for steering movements. He’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it, just drive it.’ You couldn’t get across to him that if you were going to take on Spa or the Nürburgring you had to have a decent office to go to work in.

Buy 1965 season included races in Willment Cobra Coupe, here at Oulton Park Tourist Trophy

Motorsport Images

“The only wind tunnels then were scale model jobs, and of course when you drove the cars on the track you found out things that didn’t happen in the wind tunnel. What happened with Chris Irwin was pretty nasty. [Irwin had a near-fatal crash at the Nürburgring, apparently when his F3L left the ground.] And development testing was difficult because, if we moved that there and put that there, it upset Len’s ideas of aesthetics and drag. So as well as having a very beautiful looking car you had a car that was very difficult to drive. At Spa I got it on pole [4.4 seconds quicker than next man Jacky Ickx] but what a bloody handful down through Stavelot. You’re thinking, shit, this is all a bit hard, and you ease back three seconds a lap and it’s still difficult to drive. It had a mind of its own, and I never knew quite what the hell we were doing with it.” The P69 never started a race. At the end of 1969 the project was scrapped and Alan Mann went into the aircraft business.

In early ’69 the very new, very unsorted Porsche 917 was known to be a scary beast. Having only lasted half a lap at Spa, it was due to have its first proper outing in the Nürburgring 1000 Kms. But none of the Porsche works drivers wanted to race it, preferring the more predictable 908s. On the Wednesday evening, at home in England, Frank got a phone call from Huschke von Hanstein asking him to step in.

“‘I haven’t even seen the car,’ I said. ‘It’s a bit late to be climbing into something to do a thousand kilometres around the bloody ’Ring.’ ‘Ja,’ says Huschke, ‘but ve vill pay quite vell.’ So I got caught between greed and common sense. But I said I wanted a co-driver who would keep the car on the road, and I asked for David Piper. Next day off we went to Germany.

“It was a bloody awful thing. At about 5000rpm it had 300 horsepower and then over the next 1000rpm it jumped another 200 horsepower – and the throttle was terrible, because they had the leverages all wrong. So you were busy trying to balance the power curve and not getting on the power too quick coming out of corners. The chassis flexed so much they filled the tubes with helium and rigged up a pressure gauge so that if the gauge dropped you knew the chassis had cracked. They said if the gauge went down I was to drive it back to the pits. Bugger that, I said, if the gauge drops I park it.

“Of course, in the middle of the race there was a hailstorm. ‘Vy vas this part of the lap slower than on the last lap?’ ‘Because, Huschke, on that part of that lap I frightened myself fartless.’ That didn’t go down too well. Later on the 917 became one of the finest racing cars in the world, but that early car could spring a boxful of surprises on you. You had to stay below the surprise package if you wanted to get it home and pick up the money.” Which is what Gardner and Piper did: after more than six hours’ racing they finished a very brave eighth.

In 1970 Frank set up his own shop at Fair Oaks Aerodrome in Surrey, where he adapted an ex-Bud Moore Trans-Am Mustang for British saloon racing, and got stuck into Formula 5000 with a Lola T190 loaned by Eric Broadley. Frank modified it extensively and by mid-season, with longer wheelbase and wider track, he had turned it into a very effective weapon, and first time out in this form he beat F5000 champion Peter Gethin. This led to a very close working relationship with Broadley – whom Frank rates as one of the best people he ever worked with – and Lola’s new recruit Patrick Head. Soon Frank wound up his Fair Oaks operation and moved to Huntingdon.

Frank was admired for his engineering skills, as well as being a fine driver

Motorsport Images

His modified T190 became the prototype for the 1971 Lola T192, but mid-season Frank proposed a smaller, lighter car based on a strengthened F2 chassis. Six weeks later the T300 appeared, and was rapidly turned into a race winner, helping Frank to take the European F5000 Championship title. “Formula 5000 had good people at the time: Peter Gethin, Mike Hailwood, Brian Redman. You knew you had to get your arse into gear when the flag dropped.” His big saloon mount was now a Chevrolet Camaro. “The Mustang and the Camaro were two entirely different cars. In the wet the Mustang was a delight, the Camaro was a bloody handful. But provided you had enough common sense to say, well, that’s about it, then all was well.”

The Tasman and Springbok campaigns continued, and Frank had a lot of success in South Africa in Mike de Udy’s Lola T70s. When the Tasman Series opted for Formula 5000 he campaigned a works Lola, and won the New Zealand GP in 1972. He damaged his back in a big accident the next week at Levin, when the Lola’s engine cut out mid-corner and he went off the road. He built up a new car for the Australian GP, finishing second, but decided to make it his last single-seater race.

After more success in the Camaro – which earned him the title of British Champion Racing Driver in the short-lived Tarmac Championship – Frank, his wife Gloria and their two children returned to Australia for good at the end of 1974. He put together a fearsome F5000-based Chevrolet Corvair, winning the Australian Sports Sedan title in 1977. Then he hung up his helmet.

“We’d gone to so many funerals when I was racing, the Jimmy Clarks, the Mike Spences, the Jo Sifferts, the Jo Bonniers. I competed in quite a few cars along the way, but I never wanted to be the fastest racing driver of all time. I just wanted to be the oldest. But the people I worked with – Eric Broadley, Alan Mann, Patrick Head, Alan Smith on engines, Mike Hewland on gearboxes – they were what made it worthwhile. They were a different breed.”

Frank Gardner is a different breed, too. These days, when much of motor racing is stifled by PR releases, sponsor-speak and political correctness, he is a breath of no-nonsense fresh air. Never was the cliché more true: they certainly don’t make them like Frank any more.