A year on, the duo lashed together an altogether more extreme dragster with six wheels and a monstrous 450bhp Continental radial engine housed out back: it would do until a blown Allison V12 – all 27 litres of it – became available. “I traded a $50 electric motor against it,” Art recalled in 2002. Ever more elaborate machines followed, Arfons winning the 1954 World Series of Drag Racing and becoming one of the first drivers to reach 150mph in the quarter mile with his four-wheel-drive Green Monster 6, the half-siblings having by now parted ways. Art famously beat the hitherto dominant Floridian Don ‘Big Daddy’ Garlits on his home turf in 1959, and aeroplane engines were subsequently outlawed from frontline competition. Match-racing Walt Arfons’ creations in exhibition events paid the bills but ended in mutual enmity – a situation not helped by the fact that their workshops were situated side-by-side.

No matter, Art had bigger fish to fry, his Allison-powered Anteater chasing the Land Speed Record in 1960. Intended to resemble his idol John Cobb’s Railton Special, this distinctive creation was unsuccessful in several attempts, making a best of 313.78mph in ’61 with a burnt-out clutch.

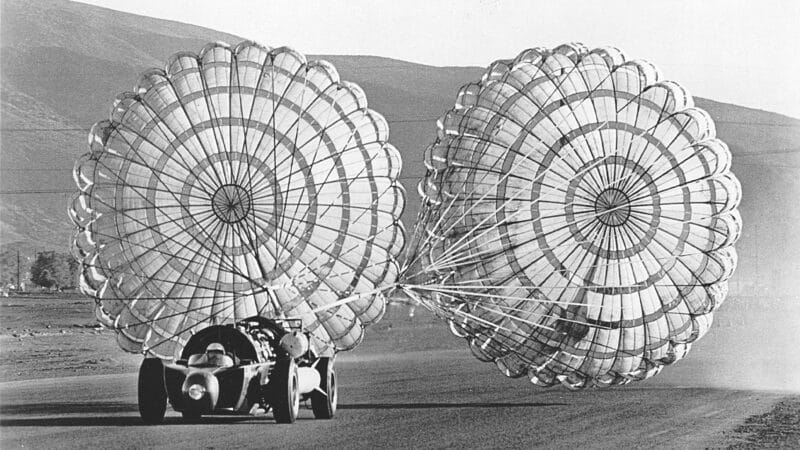

That year Arfons and his fellow hot rodders were given a wake-up call by the arrival of Dr Nathan Ostich’s jet-propelled Flying Caduceus. While it didn’t claim the ultimate prize, this contrivance clearly represented the future. Arfons used his connections in army surplus to land an engine out of a B-47 bomber for his next challenger, the resultant Cyclops making 338.791mph at Bonneville in 1962 – on remoulds. And with an open cockpit.

At the wheel of ‘Cyclops’ in 1962 – when the parachutes did work…

Getty Images

Four jet cars had turned up in Utah that year, Craig Breedlove’s among them. In 1963, the charismatic Californian smashed the 400mph barrier. Knowing that he couldn’t match his rival’s budget, Arfons did what he did best: he started scavenging. After locating a J79 jet engine that produced 17,500lb of thrust (compared to the J47 in Breedlove’s Spirit of America that made 5200), he handed over just $700 and dragged it home. It had failed after a shard of metal had been sucked into the intake and damaged 60 turbine blades and should have been scrapped – a point not lost on the government after Arfons contacted General Electric for a manual. A day later a senior Air Force colonel arrived in Akron demanding the engine be returned: it wasn’t intended for civilians. “I showed him my receipt and said it was junk and you guys threw it away,” Arfons later recalled.

Predictably, GE refused to help so Arfons stripped the engine and made repairs himself. Then, needing to test it, he strapped the jet to a chassis chained to two trees behind his workshop – and lit her up. The engine was eventually found 50ft away after it had incinerated a chicken coop and mowed a path through woodland. The fuzz weren’t impressed. Nor his neighbours whose foundations had been rattled.