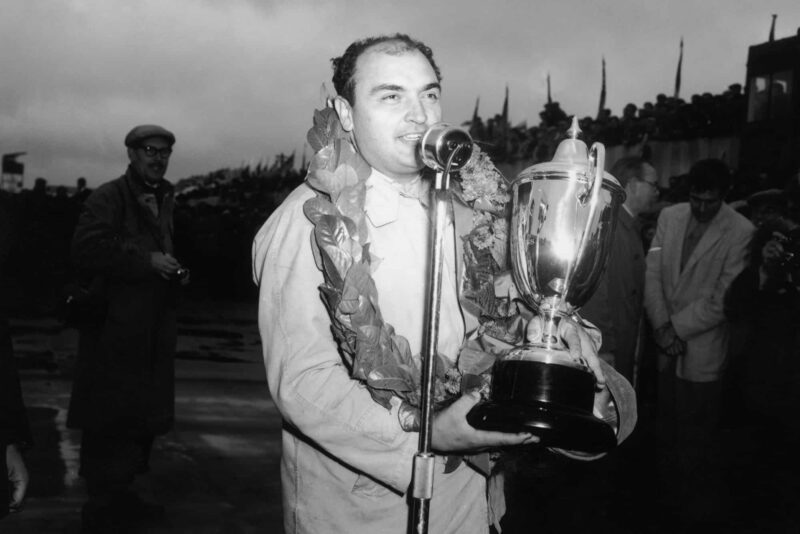

Legends: Froilan Gonzalez

Jose Froilan Gonzalez on his way to winning Ferrari's first World Championship grand prix at Silverstone

Getty Images

When Michael Schumacher won the Belgian GP last year, it was just another Sunday in a Ferrari summer. But Michael’s 10th victory of 2002 was also the 100th win for a Ferrari using Shell, and a happy consequence of that was the presence, at Monza, of the man who had scored the first.

Jose Froilan Gonzalez’s victory in the 1951 British GP was not only the first on Shell, but the first for Ferrari since the inception of the world championship. Now, a month before his 80th birthday, he was back in a paddock again, and looking extremely well on it

In his racing days, Gonzalez was indeed a burly fellow, but Stirling Moss can attest that there was nothing awry with his fitness: “It was solid muscle, boy, believe me.” Now, in old age, he seems about half the size he was.

He bursts with good humour as he remembers his racing days, speaking quickly, laughing often. And he makes his elevation to the top level of motor racing sound deceptively straightforward: “Fangio went over to Europe in 1949, and the following year I came over, driving for the Automobile Club of Argentina, racing as Scuderia Achille Varzi. We drove Maserati 4CLTs, in the dark blue-and-yellow colours of Argentina, but they weren’t very competitive or reliable.”

“That day I signed an autograph for Jackie Stewart — I think he was 11 or 12 — and he says he has always kept it.”

His luck was little better in F2 races, driving a Ferrari 166 for the same team, but at the end of the year, back in South America, the cars were supercharged for use in the Formula Libre Temporada, and he twice finished second to team-mate Fangio.

At the beginning of 1951 a couple of races were run in Buenos Aires, and these proved crucial in Gonzalez’s progression in racing. Mercedes-Benz made its return to the sport here, entering three of the W154s which had dominated the 1939 GP season, one of them for Fangio. In his supercharged Ferrari, Gonzalez flayed them in both races, and that registered in Maranello.

“After that I had a good relationship with Ferrari. When I arrived back in Europe, I went to see the Commendatore, and I told him that if he needed me, obviously I would be very willing to drive for him.

“There were to be four Ferrari drivers: Ascari, Villoresi, Taruffi and Dorino Serafini. But when Serafini broke his leg in the Mille Miglia, Ferrari asked me to drive for him at Reims.”

Gonzalez adapted readily to the 4.5litre Ferrari 375, qualifying sixth, then in the race handing over to Ascari, whose own car had retired.

“I came in to refuel and the team director said, ‘Unfortunately, Ascari has to get in the car’. There wasn’t much I could do — I didn’t have a contract then! They were trying me out, that’s all. Ascari eventually finished second and got six points — but they were split between us. It was the same for Fangio, who won for Alfa — he took over Luigi Fagioli’s car.”

Gonzalez receives a well-earned kiss from his wife after winning Ferrari’s first World Championship race

Getty Images

After Reims, Fermi called: “He said, ‘If you want to race Serafini’s car all season, you can’. Then we made up a contract. To be honest, I didn’t even know what it said! So I asked the Commendatore, ‘Are all your drivers insured?’ He said they were, so I said, ‘Okay, that’s good, I’ll sign!’ I got a wage — I think Ascari, Villoresi and Taruffi got 50 per cent of the starting money, which was about $2500— and he also gave us some money for expenses.”

Next on the agenda was the British GP at Silverstone, a track at which Gonzalez had never raced before. And he rather stunned everyone by taking pole position — by a clear second!

‘Ah, Silverstone ’51. There were four cars on the front row: myself, Fangio, Farina and Ascari. At the drivers’ meeting they said that the first one who moved (jumped the start) would get a one-minute penalty. We were all so frightened that none of us moved, and all three cars on the second row went straight past us!

“At the first corner I was back in fifth place, but I passed Felice Bonetto for the lead on the second lap, and Fangio, who’d lost even more places, got into second place. Then it was a fight with him all the way.”

As he had at Reims, Ascari retired, but this time there was no question of Gonzalez being asked to hand over to him: “I was waiting for Fangio to stop for fuel before me. I had a lot of fuel on board, but his Alfa had far higher consumption. Ferrari were signalling every lap for me to come in, but I knew I was okay because I still had not used the reserve tank. Of course, there was no way I could tell them — no radio in those days.

“Ah, that was a race! It was my first win, and also the first for Englebert tyres in F1. Two of the Ferraris were on Pirelli, because of the money; the other two were on Englebert — also because of the money! But we didn’t get any of that. It all went to Enzo!”

Photographs of Gonzalez that day, always apparently on opposite lock, chime with me like those of Fangio’s Maserati 250F at Rouen in 1957. I told him I had been at Silverstone, aged five, and he grinned: “No! Well, that day I signed an autograph for Jackie Stewart — I think he was 11 or 12 — and he says he has always kept it.”

It rained for 16 or 17 of the 24 hours, and I drove something like 4000km on my own!

At the end of 1951, Alfa Romeo withdrew from grand prix racing and Fangio decided to go to Maserati, persuading Gonzalez to join him there: “I didn’t want to leave Ferrari — and Ferrari wanted me to stay there — but Maserati paid better. A little bit more money was important in those days.”

In terms of results, the next two seasons were desultory ones if you were not a Ferrari driver, but Gonzalez supplemented his income by also driving the BRM V16 in selected races. Moss, I said, reckoned it was the worst car he ever drove…

“No, no, no! Actually, I think Stirling was very afraid of that car. BRM gave Fangio and myself £1000, and we divided it between us, to do the testing for one year. Yes, there were many problems: when you started to brake, and you wanted to turn in… you just went in another direction!

“At Albi in ’53, I finished second, but the big problem was always with tyres. Ferrari stretched his engine from 4.5 litres to five, thinking he could fight against the BRMs, but we passed them on the straight as if they were standing still! We had to be very careful, though, because the tyres kept coming off the rims. That happened to me on one lap and a huge piece of tread hit the side of my helmet!”

Gonzalez addresses the the Silverstone crowd after winning

Getty Images

For 1954, Gonzalez returned to Ferrari and had a superb season, again winning at Silverstone (the GP and the Daily Express Trophy), and taking a magnificent victory, with Maurice Trintignant, in the Le Mans 24 Hours.

“That was my most spectacular race. Very difficult. It rained for 16 or 17 of the 24 hours, and I drove something like 4000km on my own! It was a fight with the Jaguars, particularly the Rolt/Hamilton car. The Jaguar was better than the Ferrari in the wet, but we had more power. Two hours from the end there was a storm, but we were still ahead. Then, with half an hour left, we had our last stop, for a bit of fuel, and the engine wouldn’t restart because the ignition was soaked. Finally, after more than seven minutes, they got it going and we were able to win — by less than four kilometres.”

A few weeks later, though, came the tragedy which was ultimately to bring about the end of Gonzalez’s career in Europe. In practice for the German GP at the Nürburgring, his close friend Onofre Marimon crashed his Maserati and was killed instantly.

“Marimon went off, hit the trees, and that was it. It was a nightmare”

“Today, if a driver dies, it’s a big tragedy, but in those days you had about a 50 per cent chance of surviving. At circuits like the Nurburgring, there was no safety: Marimon went off, hit the trees, and that was it. His father and mother were there, and my parents, too. It was a nightmare.”

Gonzalez, demented with grief, drove in the race, and even led for a while, but eventually handed his car over to Hawthorn.

“I started to have a lot of problems with my wife because of Marimon’s accident. My parents didn’t want me to race anymore, either — they all put a lot of pressure on me to stop.”

Gonzalez continued to race in South America, winning two titles in a Ferrari, but it was left to Fangio to fly the flag abroad. His friendship with Fangio was a lifelong one and Gonzalez reveres his memory: “There were some strong drivers — Ascari, Moss, Farina sometimes — but I think Juan in those days was like Schumacher today: he always had an ace up the sleeve.”