They could chive eight abreast for half a mile towards the Byfleet Banking; we have to trickle between a parking pound and a motorcycle training slalom to regain the straight beyond that obstructive shed. Here the ancient concrete is a parking lot for buses; we divert again, this time through smarter industrial areas. By poking the Bentley’s mesh-screened snout down every possible side road, we hit pay dirt again: right behind AC Cars, home of the Cobra, a rising lip of green moss-covered concrete marks the beginning of the Byfleet Banking.

Not so high as the north end but even grander in scale, this section swept the cars in one relentless plunge through more than 180 degrees to fire them back towards the ffill. It must have been arm-aching in your friction-damped Bentley, the chassis jouncing and thumping for endless seconds as you fought to balance gravity and centrifugal force, all the while looking up and left over the screen to try and keep within your private artificial horizon and not collect any of the tiddlers down below. We have the opposite problem. Our modern Bentley weighs perhaps a ton more than a 4H and we have only the static adhesion of its fat Goodyears to keep it plastered to the banking. There are two gaps in the Byfleet section, and all we can do, once a security gate is unlocked, is creep up the mossy slope and perch on the edge of the first.

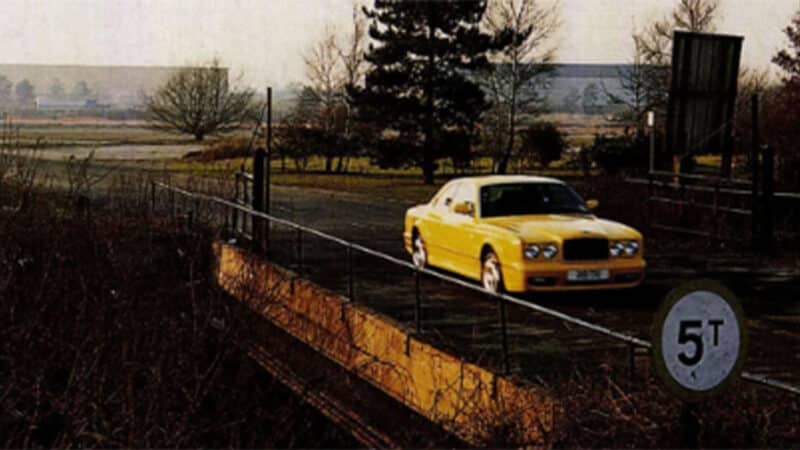

Here, just where the Byfleet Bridge once led in to the Flying Village, a new road slices through the track to feed customers into a supermarket To their credit, the road builders have made a dramatic sculpture of this, a concrete prow emphasising the 21ft height of the banking. The yellow Continental looks surreal hanging above passing Mondeos and Vectras. Across the ravine of the new road the banking runs another 200yds and once more stops dead – WWII again. Vickers-Armstrong took a swathe out to allow take-off clearance for the Wellingtons it remade here. Now trees hide the fact that the track continues, but we have insider information.

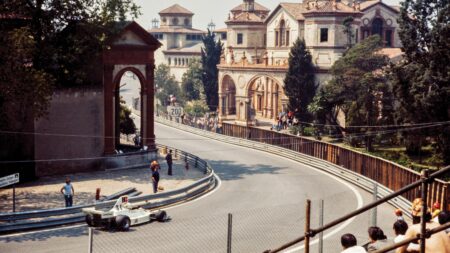

Freshly-laid circuit welcomes its first racers at Brooklands’ inaugural July 1907 meeting

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

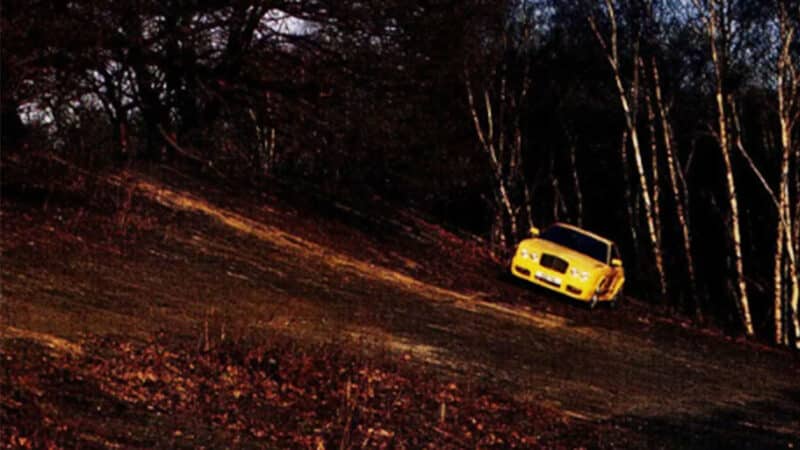

We thread between scrubby bushes, and suddenly more concrete rears up and disappears out of sight to our left. Here the southern banking is flattening down, and for a moment you almost expect to see the notorious Fork ahead – but it’s another dead stop. The River Wey again. This bridge, however, is intact; the track stops on the other side of the water. It’s not the 1907 structure, though, for floods damaged that one, and these low steel girders date from 1933. Sixty or 70 years back this was the hardest part of the circuit; not clinging to the steep bankings, but wrestling your machine down from the Byfleet Banking and setting up for the Fork. For Brooklands wasn’t just a bowl: this was a substantial right-hand bend. On the last lap you kept left and tore down the Finishing Straight, but if you were one of the big boys, an Outer Circuit racer, you had to sweep right, shaving the big shed of the Itala (later Vickers) works. Now, though, this is all gone. This is the biggest gap, the circuit’s major amputation: there is nothing left of the lower Finishing Straight, the Fork or the Outer Circuit until you reach the museum grounds again. Instead the way is blocked by a housing estate, a new access road for the Brooklands estate, and the landscaped grounds of two company headquarters. Where drivers once made their peak-revs dash for the flag, rows of company cars now park. But among the neat lawn and shrubs there’s a surprise survival: part of the pits for the Campbell Circuit. As racing moved on in the ’20s and ’30s, the groundbreaking track became seen as old-fashioned, artificial, irrelevant to modern road-racing.

Donington Park and a planned new circuit at Crystal Palace looked like serious competition. Innumerable track variants up, down and all ways round Brooklands, with chicanes of sandbanks or hay bales, only tinkered with the problem. So for 1937 the BARC laid out a road-circuit named after its designer, that Boys’ Own hero, Sir Malcolm Campbell. Parts of it can still be found. The southern end, where the new layout took a U-turn left off the Railway Straight, has gone, but the pale concrete of Aerodrome Bend, Sahara Straight and Howe’s Corner still show clearly, snaking round the barren runway and down to cross the Wey again by Vickers Bridge still extant. Beyond, the Campbell Circuit crossed the main straight and took its own parallel line back up to the Members Hill, with a new line of elaborate pits featuring roof-top viewing. It’s a section of this structure which remains in Proctor & Gamble’s car park, restored by them to carry the names It Mays’ and ‘M Campbell’ an honourable reminder that ERAs and Alfas once streaked between these neat lines of Nissans and Peugeots.