“Caracciola was the very best driver I competed against,” reflects von Brauchitsch today. “He was very good and fair, a convivial fellow. We had a good relationship for many years, both on and off the circuit. We were slightly older than most of the others and forged a deep personal bond.” Yet although Caracciola led at the end of the opening lap at the Nurburgring, it was the remarkable Bernd Rosemeyer who took up the challenge in his Auto Union. But after seven laps he was forced to make a precautionary pit stop after he had damaged one of his rear wheels against an earth bank earlier in the race.

It was not long, however, before the focus of attention fell on Nuvolari in the Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo P3. By lap seven in this 22-lap race he was up to third, trading fastest laps with Rosemeyer. Then on lap ten he stormed ahead of Caracciola to take the lead. The crowds fell silent. This was not part of the intended script by any stretch of the imagination.

At the end of lap 12 it was time for the mid-race spate of routine refuelling stops. The Mercedes W25 of von Brauchitsch now went through into the lead as Nuvolari lost two minutes topping up his Alfa. But the frail-looking Italian was not yet finished. Having resumed sixth, Nuvolari climbed relentlessly back to second place and only von Brauchitsch lay between his Alfa and an astounding victory. Nevertheless, it looked as though Mercedes had it made. The German driver went into the final lap just under 30sec ahead and it all seemed over.

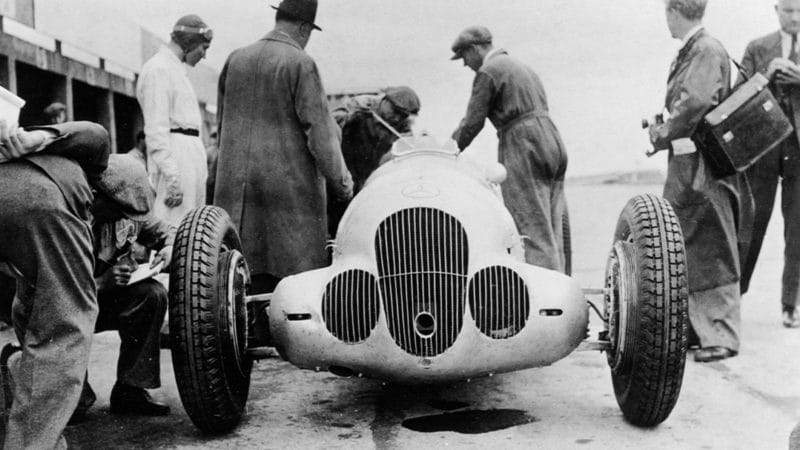

In the pits at German ’37

National Motor Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Regrettably, von Brauchitsch had been caning his Mercedes’s tyres in his anxiety to stay ahead. Mid-way round that final lap the Mercedes’s left rear tyre flew apart and the German driver was left a sitting duck. Nuvolari roared past to post possibly the most remarkable victory of his career.

“Two laps before the finish, the left front tyre started to show its marker strip which indicated it was getting down to the carcass,” recalls von Brauchitsch.

“I could see from the reaction of the spectators, particularly on the descent to Adenau Bridge, that they understood I was in trouble. After the race Neubauer blamed me because I did not stop, but I didn’t want to come in and perhaps find myself in the same sort of situation which faced Eddie Irvine at the Nurburgring last season [1999]. Not enough tyres!”

Post conflagration at Germany ’38: Neubauer and Nazi officials look on

ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Another of von Brauchitsch’s greatest disappointments came in the 1938 German GP, held once more at the Nurburgring. At the wheel of the 3-litre Mercedes-Benz W154, he and Dick Seaman dominated the race, but, as their team-mate Rudi Caracciola later recalled, Manfred was extremely aggravated by the way in which the Englishman shadowed his every move. “Neubauer, that Seaman is driving me insane,” shouted von Brauchitsch in abject frustration at his manager. “He drives up so close behind me that each time I brake, I think now we’ll crash. We’ll both end up in the ditch if this keeps on.”

While this exchange was taking place, Seaman had also pulled in for fuel behind his team-mate. Neubauer ran to the second Mercedes and told Dick to take it easy, not to hassle his team-mate. At that point the Mercedes manager glanced over his shoulder to see von Brauchitsch’s car suddenly enveloped in flame after fuel had spilled out over its exhaust pipes.