“I gave Patrick his first F1 drive, at Clermont-Ferrand in 1972, and then offered him a third car for the North American races in 73. A big chance for him — and ten days before he breaks his leg falling off a motorbike! Later, when he was driving full-time for me, I had it written into his contract that he kept away from dangerous toys.”

When Depailler’s Tyrrell won at Monaco in 1978, it was one of the days everyone in the paddock was happy. So many times before his fingertips had been on the hem of victory, but always it had slipped away.

At the end of that season he left for Ligier, and with sorrow, for Tyrrell was truly like family by now. But the Ligier proved more competitive. After winning at Jarama, the fifth round, Patrick shared the championship lead with Gilles Villeneuve, perhaps his nearest kindred soul in the sport.

Ligier’s JS11 was the fastest car of the moment, but Depailler’s rivalry with his team mate Jacques Laffite was very definitely that: a rivalry. There were no team orders, and at Zolder the two of them ran away from the rest — and into tyre troubles. Jody Scheckter’s Ferrari won, and Guy Ligier was furious. Patrick was bemused. “If you are a racing driver,” he shrugged, “surely you race…”

If Ligier was angry in Belgium, a few weeks later he was apoplectic. Unlike Tyrrell, he’d not precluded ‘dangerous toys’ from Depailler’s contact. After the Monaco GP, Patrick went hang-gliding, and severely injured his legs. He had flown too close to a mountain, and turbulence had pitched him into the rockface.

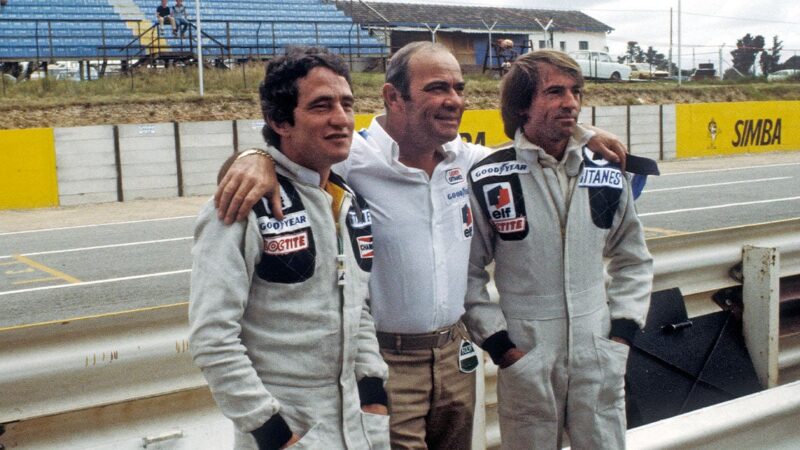

Ligier rival with Laffite boiled over early on

Grand Prix Photo

The general reaction to Patrick’s accident was chillingly hard-nosed. In commercial terms, perhaps it was inevitable, but I found disturbing the lack of sympathy for a man perhaps staring at life in a wheelchair.

When I spoke to him, he said that the worst thing was not knowing if he would recover properly. “For a time there was the chance of amputation, and I was very frightened. Not for five months was I sure to drive again.”

Without that, Patrick seemed to be saying, life would be insupportable; in his terms, being alive meant being a racing driver.

I was very fond of Depailler, not least because his attitude to life and work was refreshingly haphazard in a world where dour automatons increasingly peopled professional sport. That said, working with him must have been sometimes maddening.