Surely such success so young made him cocky? “Well, yes,” agrees Jo. “He was never so with me but when you get this overwhelming attention all over the world, I don’t care who you are, it will have an effect. Just like Schumacher four or five years ago, you become unbearable. But after a while you realise, ‘So what?’ and then, like Michael, you become a normal person again. As Ricardo got older he stopped being arrogant.” Hill concurs: “He came across as if he had been through some good social training. They both did. They were great kids.”

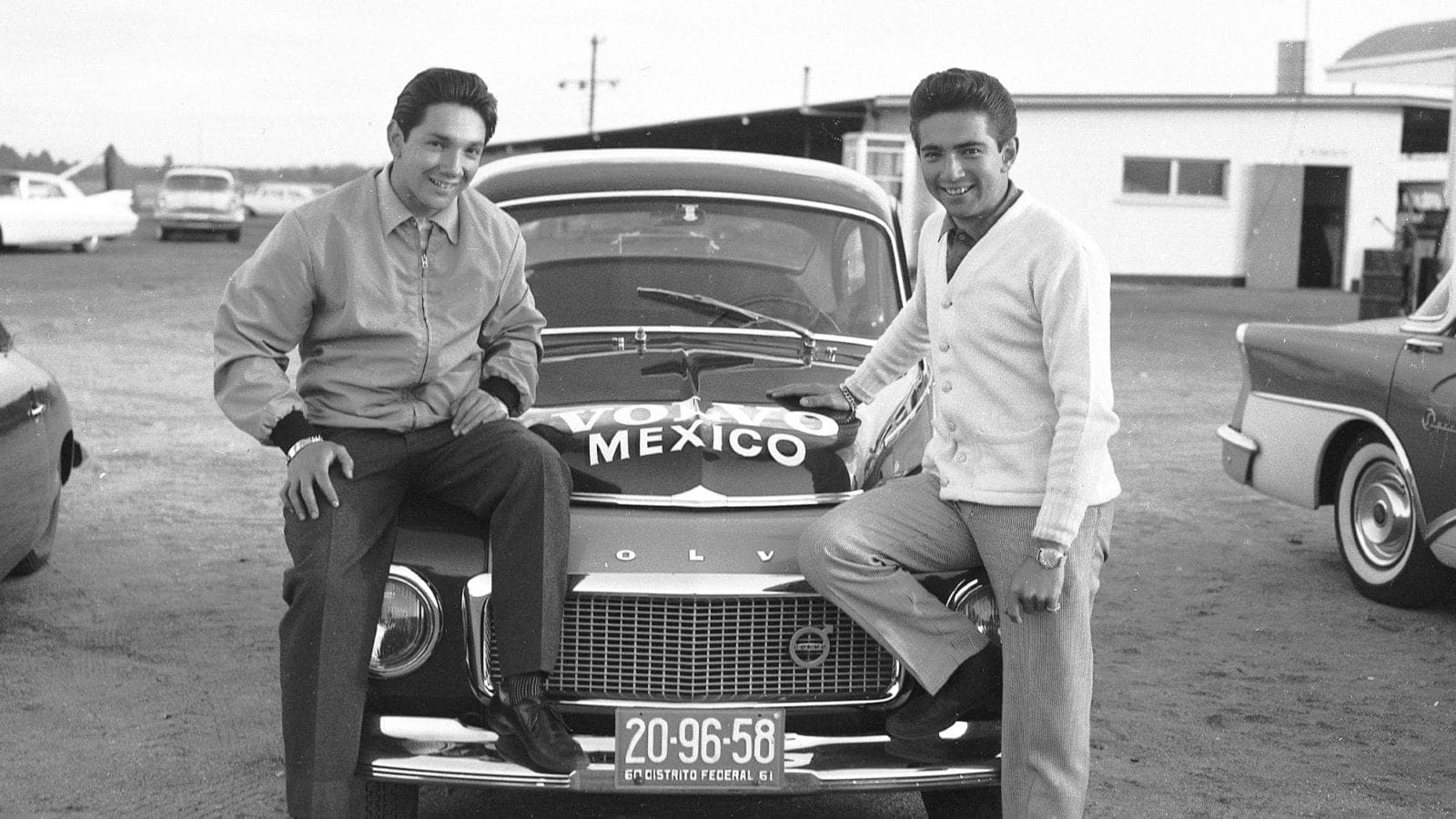

Social graces were part of the upbringing in the Rodriguez family. One of Don Pedro’s businesses manufactured containers for the country’s biggest petroleum company. There were plenty of others too and there was said to be a link to a certain Mexican president on account of the politician’s mistress being Don Pedro’s daughter. It was further whispered by some that this led to an arrangement whereby, for a cut, one of Don Pedro’s companies unofficially collected taxes from the country’s brothels.

In Ricardo, Ferrari engineer Mauro Forghieri recalls a young man of some sophistication: “Although he was young he was not immature from a human point of view. He was serious and very determined. He wasn’t as reflective as Pedro and the quality of his driving was still instinctive, but he had a good relationship with people in the team and worked hard.”

That he was not a typically hot-headed Latin was evidenced further when he married an older local girl, Sarah. “She wouldn’t let him out of her sight,” laughs Ramirez, “he couldn’t have played even if he’d wanted to…”

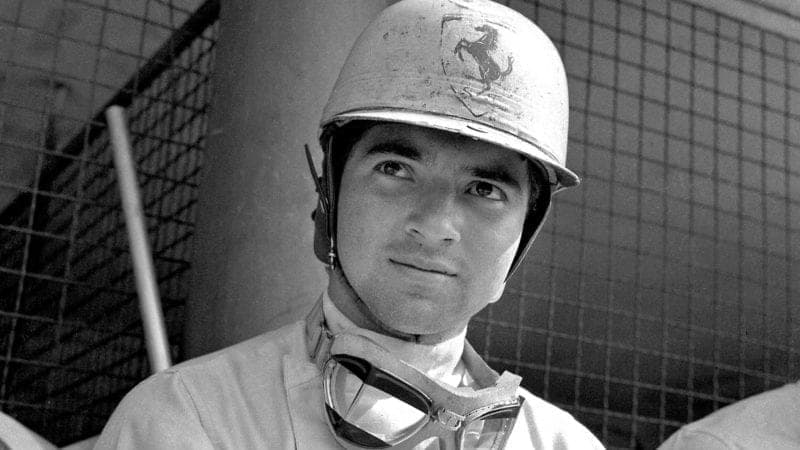

Pedro driving for BRM at Clermont Ferrand in 1970

Grand Prix Photo

Pedro too, had married young to an older woman, Angelina. After Ricardo’s death the elder brother returned to Mexico and opened a car import business. He would race occasionally for enjoyment, he decided. His brother’s death wasn’t going to stop him doing that. His introspections had brought a fatalistic philosophy. “God decides when your time is,” he would declare.

For the next four years he lived this part-time racing driver existence, doing occasional grands prix with Lotus and Ferrari, competently but without conspicuous success, taking occasional sports car wins and even having a crack at the Indianapolis 500. But, away from the pressures of being measured against Ricardo, something began to develop in Pedro. His driving became more assured, less ragged, and he began to fall in love with racing all over again. “There was definitely some strange effect on Pedro after his brother died,” affirms Hill. “He became quicker, no question.”

“Yes, he became better and better,” agrees Ramirez. “He was more relaxed.” It began to show in his form. Standing in for an injured Jim Clark at the 1966 French Grand Prix, he ran fourth before retirement and in his home Grand Prix he got up to third. It led to an offer from Cooper to fill the vacant second seat at the first race of the ’67 season, in South Africa. He won what was to prove Cooper’s last grand prix victory. It was a lucky win, but it earned him the drive for the rest of the year alongside Jochen Rindt.