“I knew Revvie very well in the Ditton Road days. One time we all went to London in one of Amon’s MkII 3.8s, Revson, me, Amon and his girlfriend. We went up to the Adlib club, a well-known joint then. We all got drunk and started being outrageous with Amon’s girlfriend, to the point where he threw us out! He told us to take the car home, and at that point Amon was buying 3.8s by the dozen and having them done up and sent to New Zealand, so he always used to drive the one that worked. Well this one worked but it had a flat battery, so we got slung out on the street about one o’clock in the morning, inebriated, and it’s parked on the footpath right outside of the club. We get the bouncers to push start the car.

“Then I’m driving home and Revson’s fallen fast asleep alongside. We get to Shepherds Bush where all those traffic lights are, and I’m sort of wandering through them and they go red so I stop. Revson stirs; thinks he’s home. He’s looking all around and he says, ‘What’ve we stopped here for?’ I said, ‘The lights are red.’ He said, ‘Yeah, but you should be stopped back there, shouldn’t you?’ I said, “No, no, you Americans don’t understand traffic lights.’ What I’d done was stop right across the middle of the intersection! So he said. ‘Well explain it to these two guys coming up here . . .’ “And there’s a couple of bobbies on the beat flashing their torches at me, so I pull in to the side. The guy says, ‘Is this your car, sir?’ So I said, ‘No, it’s Chris Amon’s, the racing driver’s.’ He said, ‘Does he know that you’ve got it?’ So I said, ‘Well, he gave me the keys, so suppose he does.’ So he said, ‘All right, but we’d like to look in the boot.’

‘Well, you know what the keyhole on a 3.8 lag’s like; tiny little key. And there’s about 27 keys on this ring, and I’m merry, it’s dark. I couldn’t see the keyhole, let alone find the key. So eventually we get the boot open and it’s all full of racing numbers, all that stuff, and he said, ‘Okay.’

At this point a squad car pulls up on the opposite side of the road and this cop yells out, ‘Everything all right, Constable?’ And the bobby shouts back, ‘Yes, it’s just a couple of drunks on their way home.’

“I’m desperately relieved, leap into the driver’s seat, and then realise the battery’s flat, so we have to get these two coppers to push start us…

“I suppose after days like that, Revvie just had to get serious, you know? I don’t know; maybe he just suddenly remembered who he was, what he was. He was like all these guys. When they’re young they’re having a good time. Sure, they all want to do well. At the time they’re not doing well, they’re all good blokes. When they’re serious, putting their mind to it, life suddenly isn’t the ball it was. They change. It’s automatic, isn’t it? By the Can-Am days he was distant. I don’t know, maybe it was because I was mates with Denny and he was the American sporting star…”

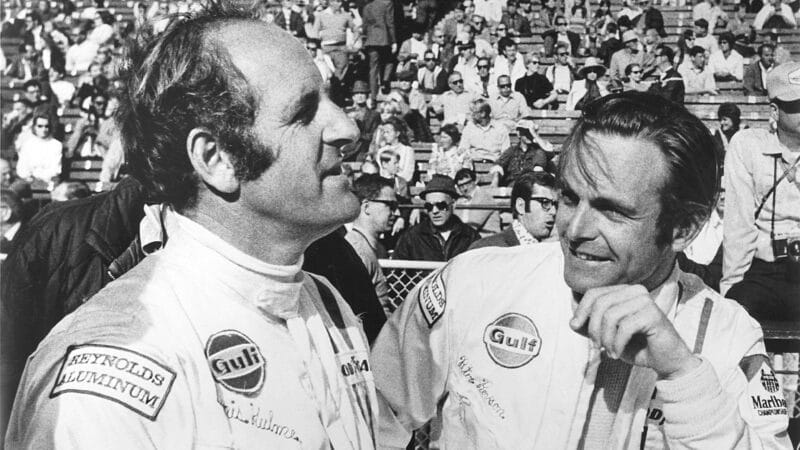

Deeny Hulme (left) with Peter Revson (right) were later potent team-mates at McLaren

Getty Images

Times might have been fun in the very early days, but Revson was disappointed with his results. A little disillusioned, he went back home in 1966 and began rebuilding his career in the Can-Am and TransAm series.

Looking back, Young reflects: “I think having his brother killed knocked him sideways a bit.” Revson and younger brother Doug had often fought, but right after the funeral, when Doug had been killed after hitting a backmarker in the rain in a Danish F3 race in 1967, Revvie had gone straight to Bryar Motorsports Park in New Hampshire. There, with grim determination, he won the TransAm race in his Mercury Cougar.

By 1969 he’d taken the unfashionably turboless Brabham BT25 Repco from 33rd on the start line to fifth place at the end of the Indianapolis 500, and quietly admitted that it burned to see Mark Donohue take the Rookie of the Year honours. The next April he partnered Steve McQueen to second place at Sebring in the former’s Porsche 908, the pair of them beaten only by Mario Andretti‘s iron determination not to be beaten by a movie star.

Revson himself had a movie star persona allied to a hard business head. He always sought to shrug off the ‘Revlon Heir’ tag, and his Lincoln-Mercury dealership in California’s Harbor City was doing well. As 1970 developed he showed class chasing the McLaren steamroller in the Can-Am, driving Carl Haas‘ L&M-sponsored Lola T220.

Haas recalls: “He and I were pretty good friends. I’d known him a long time before he drove the T220 for me. He was very personable, very serious about his racing, and a very good race driver. He turned in some good performances in the Can-Am: he pushed the McLarens hard. When he was killed he was just at a point where he was ready to become a real contender.”

The real break came when Amon finally called it quits at Indy and handed his McLaren M15 over. Chris, the man who could take the Masta Kink flat at Spa without worrying about the houses and the trees, admitted that the Brickyard’s wall spooked him. For Revson, it was the passport to the real Big Time.

“I always figured that you only get one chance,” he said, and he parlayed that drive into a regular seat. In 1971, he stunned the Indy fraternity by placing his M16 on the pole at 178.696mph. In the race he finished second, 22.88s behind Al Unser Snr.

The front row at Indy (left to right): Bobby Unser, Mark Donohue and Peter Revson

Getty Images

Former McLaren mechanic Hywel Absalom was another who liked Revson. “He was a pretty quiet guy, really. He was hyped up to be a playboy, but he really didn’t play that part at all. In those days there were a lot more flamboyant drivers about, yet he was characterised with the playboy image.

“I think he was very serious about showing what he could do, although it was better for him on the Indy front because they’d probably got more accurate American information on him. He just pulled that one out of the bag at Indy in ’71. I remember him just hanging in there on the same lap as Al Snr in the race.

“When he was killed, he was still climbing as far as I was concerned.”

There were other good things about 1971, for he had taken the regular seat alongside Denny Hulme in the Can-Am, and there he became the first American ever to win the title as his M8F carried on McLaren’s glorious North American reputation.

“There was a good picture I remember,” says Young. “I think it was Laguna Seca. Denny had been winning the race and the engine blew. It just covered the car with oil. There was a picture of Denny in the pit lane, and he’s writing in the oil on the wing ‘Go Revvie!’”

For Young, any warmth from their original Ditton Road relationship had more or less evaporated by the time they worked together on the Can-Am scene, and by then Young’s involvement with McLaren was winding down to a deal as Gulf’s public relations man. There were nevertheless some amusing moments.

“Revvie was walking away with the race at Mid Ohio, so around lap 60 of the 80 I wrote the Gulf press release and had it all photocopied before the race finished. Then, just as I looked up, he went past trailing a cloud of smoke!” A halfshaft joint was failing. “I tore up all the releases, except for the original, which was still in the machine. While I went off to find out what had happened, the guy in the press room found the original release and photocopied it all over again, and then began handing them out. Revvie was fit to be tied when he saw them!

“By that time Denny was still Denny, but Revvie was…someone else. He became an…well, I didn’t like him.”

Revson prepares with a serious demeanour

Grand Prix Photo

Parnell has different recollections of the man. “Every time he ever came to England he always used to ring me up. When he was killed in South Africa, we’d all gone out together on the aeroplane because I was out there testing with BRM. We were ragging him at the time because he was involved in all that Miss World thing. And of course, me being a football chap as well, connected with Derby County, knew that Marji Wallace was also going around with Georgie Best. We used to rag him about that!

“He was a terrific pedaller by the end. A real nice guy, was Peter Revson. You’d have a joke with him about anything. I didn’t notice any change in his character; to me he was always the same, was Revvie.”

At the end of 1971 came the thing Revson was beginning to want most of all: another crack at grand prix racing. “Being an American, Indy is the race I really want to win, but where I want to race is Formula 1. That’s my big challenge,” he would tell reporters.

There were suggestions that Goodyear had bought him the ride in Ken Tyrrell’s third car at Watkins Glen, but works manager Neil Davies recalls: “We took him because he was a very promising young driver.”

They weren’t the only ones who now felt that way. Though he qualified 19th only to retire on the first lap with oil on the clutch, Teddy Mayer was interested in his services for more than just USAC races in 1972. He would stand down from the Can-Am (although plans to supplant him with Jackie Stewart eventually foundered through JYS’ ulcer), and step into the F1 team alongside Denny. Seven years after that first abortive sortie, he was back. And this time it was very different.

By his own admission he learned a great deal as the year progressed, despite often having to switch each weekend between F1, Indy and the Can-Am. He did nine of the 12 GPs, and there were thirds in South Africa, Britain and Austria to add to fourth in Italy, a fifth in Spain and a seventh in Belgium, where he fought back in style after a puncture. Best of all was pole position in Canada, where he finished second to Stewart after a brilliant recovery fight with Ickx, Regazzoni, Fittipaldi, Hulme, Amon and Reutemann after his throttle had originally jammed in the closed position. In the qualifying stakes, he edged Denny out five races to four, and he was fifth in the world championship.

“A promising young talent”: Revson lines up for McLaren at Brands Hatch, 1972

Getty Images

Though he was disappointed not to have won a race that year, his improvement had caught many eyes. “Brands Hatch in particular was a very good drive,” recalls Autocar & Motor Grand Prix editor Alan Henry, who covered the race for Motoring News. “He was the only driver on the same lap as Fittipaldi and Stewart by the end of the British GP.”

1973 would be better still, the year in which he finally established himself as one of the world’s leading drivers, but the first half was relatively barren. He was second to Stewart in South Africa, fending off Fittipaldi by a scant half second, fourth in Spain and fifth at Monaco, but Denny comfortably aced him in qualifying. He was close, but somehow not close enough, to achieving his aspirations. He maintained there was something amiss with his M23. And then came Silverstone.

Round the Northamptonshire track he parked his McLaren on the front row, alongside Peterson and HuIme, and when all the dust from team-mate Jody Scheckter‘s carnage had settled and Stewart had got two gears at once at Stowe, Revvie calmly picked off Ronnie Peterson for the lead on lap 39. The Swede counterattacked, but the American kept his cool and with great precision swept home to win his first GP by 2.8 comfortable seconds. To add to his pleasure, the night before he’d backed himself for £150, with £50 each way at 14 to 1. He netted an easy £875 extra prize-money.

Fourth place followed at Zandvoort, and third at Monza where he’d started from the front row again. In Canada he was again second fastest, and in a wet-dry race of total confusion he was eventually named the winner after everyone’s lap charts had blown up. That one might have been a gift, but after Stewart had kept Kyalami despite passing under yellow flags, maybe he’d been owed a little good fortune.

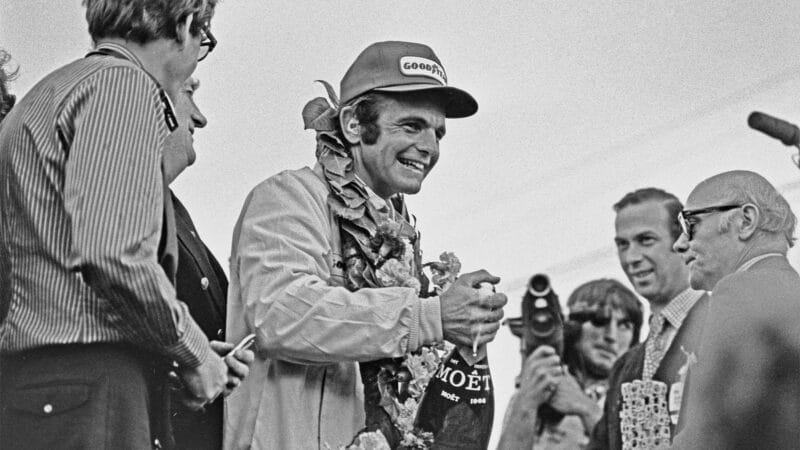

Revson celebrates his first GP victory at Silverstone, 1973

Getty Images

Again he was fifth in the world championship, and now there was little doubt about his prowess. Peter Revson was maturing nicely. “At the end of the day,” said Henry, “at Silverstone he beat Denny, Ronnie, James and Emerson fair and square . . ”

Henry always liked Revson. “He was good looking, and scrupulously polite. I thought he had a lot of star quality. There was an aura about him, which was enlivened further when he turned up at Watkins Glen in 1973 with Miss World, Marji Wallace, on his arm. I hadn’t been doing F1 long then for Motoring News, and I suppose I was a bit star struck with him. I interviewed him in a camper at Mosport Park, just before he ‘won’ that race. Actually, the camper belonged to a wealthy retired businessman called Bill ‘Spanky’ Smith, with whom Revvie had become friendly. That was quite a big deal then, you know: Smith had a camper before people in F1 had campers, and Revvie would hold court in it.

“He wasn’t necessarily world class but he was a lot better than some people perceived him to be at the time. He was probably better than Denny in 1973, and Denny had won in Sweden and been on his only pole in South Africa. The M23 was a hot car then, of course, but Revvie was good.”

His racing philosophy was simple. He always sought a car’s limits, but he did so in a controlled manner. His approach was always calculated, and the title of his biography said it all: Speed with Style. And, though a slender six footer, he was tough. He once ran Joe Frazier close in a weight-lifting contest.

Revson once told the writer Ken Purdy: “I began to understand that I had to learn to be conscious of everything I’m doing, to anticipate, to be deliberate, never to lose myself, never just to slam my foot down and go, and above all to concentrate, to turn off absolutely everything in my mind but what I’m doing – everything.”

There were, however, clouds on the horizon. There had been, indeed, since July 28 at Zandvoort, only a couple of weeks after his Silverstone victory. Mayer had informed him that he was out of the F1 team for ‘74, and offered only F5000 and USAC races in the States. He was then swept into an unsettling maelstrom of political wrangling. Of Mayer’s advice that he wasn’t wanted, Revson retorted laconically: “It seemed that Teddy’s sensitivity index was particularly bad.”

Revson prepares for his last race with McLaren on home soil at Watkins Glenn

Getty Images

Mayer had former world champion Emerson Fittipaldi waiting in the wings, with Marlboro in tow. Marlboro wanted Hulme to stay and Denny was keen for one last season. You didn’t need calculus maths to see that three into two wouldn’t go. Already hotshoe Scheckter had got the message and started taking with Tyrrell.

Henry: “There was high inflation in ’73, and that affected the Yardley deal. Basically it had agreed terms to stay with McLaren for 1974, putting in the same as it had in ’73. Then along came Marlboro with Emerson and three times the money…

“Yardley actually issued a statement that just tore McLaren apart. Teddy threatened legal action if the press quoted from it, and to be honest because I’d only been doing F1 for a short while I didn’t have the nerve to go ahead. If it was today, we’d just have told Teddy where to go!”