Le Mans 1995: introducing the F1 GTR

It’s 30 years since McLaren stamped its mark on La Sarthe – as recalled by designer Peter Stevens

Getty Images

Much has been written about the McLaren F1 road car; it is now 30 years since five McLaren F1 GTRs finished first, third, fourth, fifth and 13th at Le Mans in June 1995. The F1 had been launched at the Monaco Sporting Club in May 1992. During those 33 years, myth, hearsay and rumour have both enhanced and clouded the history of a sports car that continues to fascinate enthusiasts.

Memory is, of course, an unreliable tool when writing or reading an article or book. We edit our recollections and find it difficult to recall complete conversations, even though they can give veracity to a tale. But luckily, I had got into the habit of writing copious notes in many A5-size notebooks.

A fairy tale Le Mans for the Ueno Clinic-sponsored McLaren.

Getty Images

The team at McLaren Cars was small for a project of such complexity as the F1, but some were friends from Lotus, where I was before McLaren, and with the others we gelled into an enthusiastic team, who are still good friends today. Although there was not a suggestion that this might be a racing car, I couldn’t help trying a few things in the wind tunnel to see how tuneable it might be should that next step occur.

It was never my objective with the road car to produce a high-downforce design. With an expected top speed of around 220mph you really want a safe and stable car, but not one that needs springs as stiff as a pick-up truck at normal road speed to cope with the loads at over 200mph. I had used both McLaren’s preferred wind tunnel at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington and the very old tunnel at what was the Brabham factory. And finally, the MIRA full-size tunnel to confirm our results.

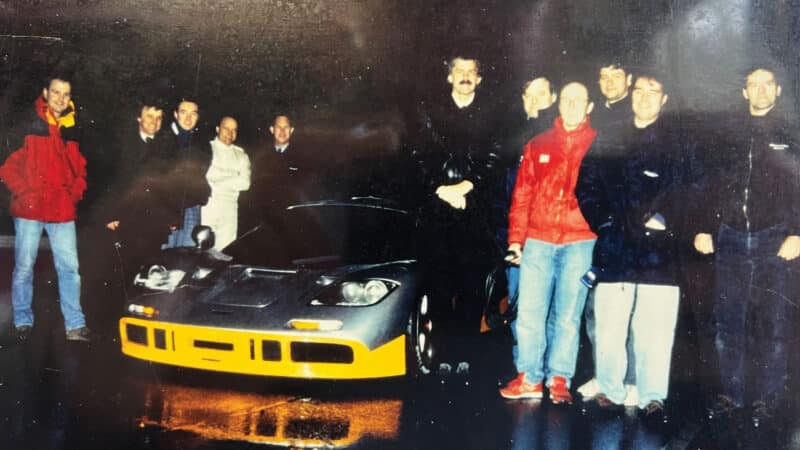

Chobham test track with the McLaren F1 GTR mule, just six months before Le Mans 1995

Peter Stevens

I had left McLaren Cars by the time both Ray Bellm and Thomas Bscher had persuaded McLaren’s Ron Dennis to produce a version of the F1 in early 1994 that could run in the BPR GT1 race series. Good friend David Price called me later in the year to ask if I would like to come on board as a consultant with his DPR team who were going to run a McLaren F1 in the BPR. His thinking was that having been with the project since its start in 1988, I might know where we could improve the car for the 1995 season. We would have to run on Goodyear race tyres since Michelin had signed exclusively with Bellm’s Gulf McLaren team. Goodyear had a very limited range of compounds, while Michelin had a huge variety, with a choice of intermediate wets, so we were at a disadvantage.

“Ray Bellm and Thomas Bscher persuaded Ron Dennis to produce an F1 for the BPR GT1 series”

Price agreed that we had to be clever. Steve Randle, who was chiefly responsible for the suspension and dynamics of the F1, had given me a copy of a graph of the chassis stiffness which showed from the rear bulkhead back the car was as stiff as a wet fish. We developed a tubular steel structure mounted from the bulkhead back to the rear suspension mounting points, and – hey presto – the car responded to rollbar adjustments. Also, the car could not be run much lower than the road version because the front tyres would hit the outer edges of the windscreen and the supporting flange of the carbon monocoque. Both of these were radically modified.

An F1 GTR at Jerez in 1995’s BPR Global GT Series.

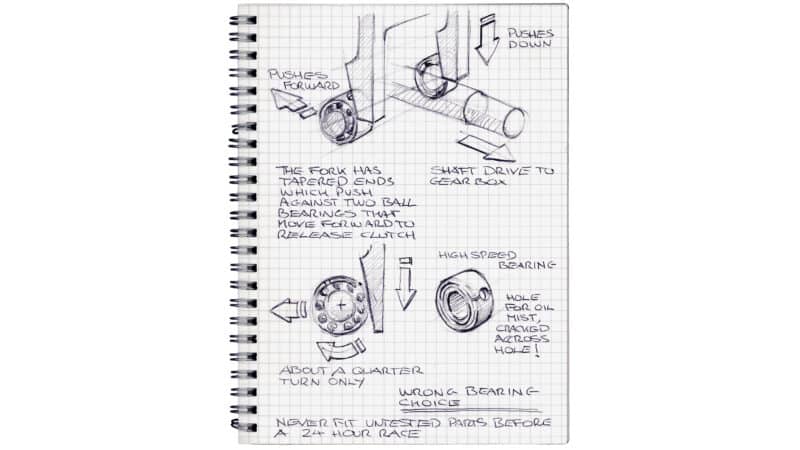

Peter Stevens’ sketch highlighting the clutch problem and ending with a forlorn ‘memo to self

Peter Stevens

The Ueno Clinic Le Mans winner of Yannick Dalmas, Masanori Sekiya and JJ Lehto was, in fact, the factory prototype F1 GTR

Sutton Images

Of the seven F1 GTRs in the race, five finished, with Peter Stevens’ Harrods car finishing third – to the delight of the pitcrew

Getty Images

The basic car was prone to understeer due to a lack of front downforce so we modified both the front splitter and splitter underside. I worked with DPR engineer John Piper on these modifications and also with an aerodynamicist friend from Lotus, John Davies, who supplied us with drawings for a two-piece rear wing which had less drag and was more easily tuneable. Piper came up with a simple system that allowed us to change slide-in Gurney flaps during a pitstop, according to race conditions. Our Harrods-sponsored car had arrived late for the team. The DPR mechanics had to finish building the car in the pit garage during the April 1995 Jarama race.

“The basic car was prone to understeer so we modified the front splitter and splitter underside”

Later in April was the Le Mans pre-qualifying where John Nielsen was the fastest McLaren. The factory then ran a 24-hour test at Paul Ricard during May to further upgrade modifications which would be passed on to the other customer F1s, using the No01R mule – which would ‘magically’ find its way into the race when a Japanese customer wanted a last-minute entry. During practice and qualifying for the 24-hour race we had already identified a clutch-thrust withdrawal bearing problem with the stipulated heavier Le Mans clutch. This had two high-speed needle roller bearings with an oil mist lubricating hole drilled in the casing. This was prone to fracturing across the hole due to the much higher clamping loads caused by a heavier clutch plate and the entry of carbon clutch dust into the bearing. John Piper and I were sent out by David on Friday morning to try to find some more suitable bearings, either sealed or plain. Despite visiting more than 20 possible bearing suppliers we found nothing suitable. David said if nothing was found by 5pm we would have to build the cars knowing that we were likely to have problems. This famously came to pass, of course. Gordon Murray would say later that we should have taken his advice and fitted the old-style clutch plate, but we were working on information that the new plate had done a 24-hour test at Ricard, which it later transpired it hadn’t.

A phalanx of F1s at Le Mans in ’95; seven started

Getty Images

Harrods No51 notes show Justin Bell’s lack of laps

Peter Stevens

In any case, to quote chief mechanic Ted Higgins. “The two DPR cars had a good early race, Nielsen leading in the West car after a four-hour opening stint, and Wallace ran a three-hour stint, so both cars were right on it. Nielsen and Jochen Mass did the bulk of the driving of the West car.” As Thomas Bscher said to me, “Gentlemen don’t drive at night particularly when it’s wet.”

It was at 3am that the clutch thrust-bearing failed on the West car, and the crew changed the bearing in 79 minutes – a ‘gearbox out’ job – and at the same time someone changed the brake pads. “But whoever did it forget to put a note on the steering wheel saying it had new pads, and when Nielsen went back out, he went straight off at the second chicane,” said Ted.

Andy Wallace with Derek and Justin Bell on the podium; Gordon Murray reckons they could have won

Getty Images

McLaren had provided a little aerofoil for the wiper arm which put so much downforce on the arm that it seized the motor on the West car. Ted recalled, “We ripped the aerofoil off the Harrods car. Peter [me] told us that you didn’t need a wiper above 90mph anyway, the aero blew the water off the screen.”

“Wallace drove the car without the clutch at sufficient pace”

Harrods now led Le Mans, but Derek Bell’s son Justin was not comfortable in the dark and rain. David Price called him in because he was suddenly 15sec a lap slower than JJ Letho in the Ueno Clinic car. Derek, back in the car, was finding gearshifts difficult and spun when the selector engaged first gear with two hours to go. He handed over the car to Andy Wallace who had instructions to not use the clutch. This made starting after his two pitstops tense since he had to start the car in gear while two mechanics ‘helped the car’ into motion. Wallace drove the car without the clutch at sufficient pace to not lose third position.

The Ueno Clinic car had the old type clutch and won. A great performance for McLaren but a frustrating one for our team. Derek will always believe that we should have/could have won, while Gordon Murray still insists that we “threw the race away by not listening to him.”