The first 100mph Indy 500

It’s a century ago since the race was first run in under five hours. Here’s the story.

Getty Images

Uncle Ralph knew a trick or two, a brick or three. Indy’s handsome leading man had experienced triumph and tragedy here: 132 laps led in victory in 1915; and 196 (of 198 completed) in defeat in 1912.

Ralph DePalma was at it again in 1921 – 108 laps (of 110) – when his straight-eight engine gave short notice of impending boom! His riding mechanic leapt from the cockpit as the clattering Ballot staggered to a stop two laps later, a conrod broken. Rare were the occasions when nephew – and riding mechanic – Pete DePaolo’s gap-toothed grin wore thinly. This was one.

DePaolo with his Duesenberg in ’25; supercharging guru Dr Sanford Moss stands centre

Another had been in 1920. From the first of consecutive poles, and recovering swiftly from a puncture just prior to the formation lap, DePalma had led 79 (of 186) when flames flickered from beneath the Ballot’s bonnet. Victory and family honour was at stake. Though Pete understandably hesitated when ordered to clamber out, to put it out – while on the move. This stunt – astride the dumb-irons, back to the wind, one hand holding the radiator’s motometer, the other wielding an extinguisher – would be repeated before the straight-eight stalled finally. Indefatigable Pete cranked its starting handle feverishly but impotently before sprinting a mile for a can of fuel. He was surprised to be met midway upon his laboured return. Fuelling had been not the issue. One of the pair of magnetos had fried – and now been disconnected. Pete leapt aboard and, after removing sparkplugs to ease compression, they struggled home ‘on four’ to finish fifth.

Breathless newspaper articles and hushed hearthside chats about his famous, Italian-born relative’s exploits had fired DePaolo’s imagination. Aged 16 in September 1914, having scrimped to pay his way – ferry included – from Roseland, New Jersey, he watched agog as DePalma won all five of his races at Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach. Pete’s mind was made. Not even Frank Dearborn’s ultimately fatal accident, his Peugeot suffering a puncture while giving frantic chase to DePalma’s Mercedes, caused our chirpy teenager to pause. Nope, this was too good an opportunity to miss.

Not that his uncle mothered him. DePalma’s cars and overalls were always immaculate because Pete was forever on valet and laundry duties. And if fastidious Ralph’s Indy preparations included two weeks surviving on bread and milk, his riding mechanic was expected to suck it up. Nor was it ever suggested that DePaolo sit behind the wheel, let alone take it. A chastening spinning conclusion to a sneaky run at Indy resulted in firm admonishment – albeit after avuncular enquiry as to his speeds achieved.

DePaolo points to his son Tommy’s ‘lucky’ shoe. He raced with it wired to a front spring.

Alamy

DePaolo was an asset – and a quick learner. Emerging from the armed forces in 1919 with a ‘ticket’ in aero-mechanics allowed him to contribute as well as participate, filter as well as absorb, while sitting at this racing god’s left hand. At 5ft 7in, he was boxing/wrestling stocky – and cocky. By 1922 he had become too big for his boots. His querying DePalma’s self-defeating reluctance to use Firestone tyres, because of a long-running feud with roguish racer Barney Oldfield, was “blasphemous” as well as precocious. DePaolo would have to make his own way from hereon. That he had learned well was proved in May when he became the first – and so far only – man to lead the Indy 500 as a driver as well as a (no longer mandatory) riding mechanic. He had, however, still much to prove.

For that lead was brief – three laps, just past the 200-mile mark – whereas DePaolo’s widespread wrecker notoriety would stick. (His playing up to it didn’t help.) That he had gathered himself sufficiently within a few minutes of smacking the wall in his Frontenac, however, to steer 87 safe laps in Joe Thomas/Wade Morton’s troubled Duesenberg – DePaolo brought it home 10th – was noted by the discerning.

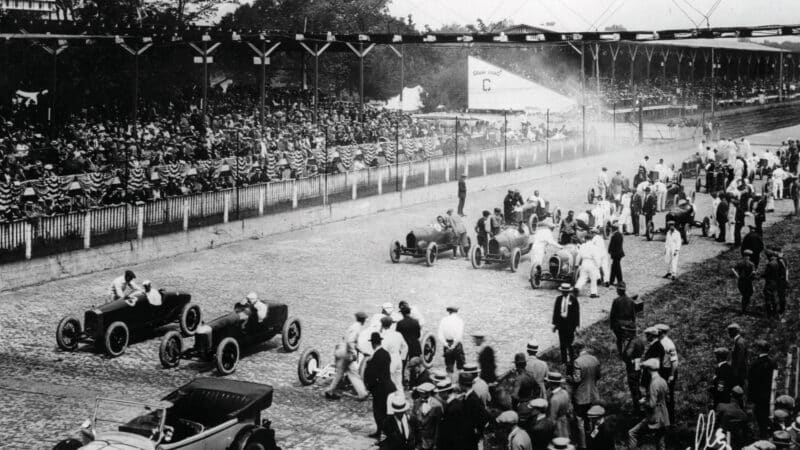

DePalma’s second Indy 500, 1912 – he led for 196 out of 198 laps before disaster struck

Potential that seemed destined for waste when a crash in September’s inauguration of Kansas City’s board track put DePaolo in hospital for three weeks – and poor Roscoe Sarles, his Miller’s broken steering the reason for their collision, in the morgue. Now DePaolo paused. New wife ‘Sally’ would soon give birth to son Tommy, and the security provided by ownership of an LA service station seemed preferable. The racing bug barely bit in 1923. When the itch returned the following year, DePaolo had to charm a doubtful Fred Duesenberg. Joining as the team’s junior, he was assigned its only old-spec car, i.e. unsupercharged.

Mercedes had introduced forced induction to the Brickyard in 1923. Its benefit was lost on some – Max Sailer’s eighth was the best that Stuttgart’s three-car effort could muster – but not on the German-born Duesenberg brothers. Working with General Electric’s Dr Sanford Moss, they fitted a ‘sidewinder’ centrifugal supercharger – better suited to the constant high rpm of US-style racing – to their DOHC 2-litre straight-eight. Mounted nearside, between low-mounted updraught carb and inlet manifold – so sucking the charge more efficiently than blowing it shrilly – a driveshaft passing between the two blocks of four cylinders spun its rotor at 40,000rpm, boosting power beyond 200bhp. A car that handled and rode better than the rival Miller was now also able to outdrag it.

While new dad DePaolo was absent from the 1923 Indy 500, DePalma, age 40, was present, lining up in the middle of row four

But cutting edge can be double-edged. Joe Boyer sliced from the second row to lead the first lap, only to slow on the second because of… supercharger trouble. His day changed for the better when he assumed more circumspect team-mate Lora Corum’s car on lap 112. The latter was holding fourth, more than 2min in arrears. Boyer retook the lead with 23 laps to go. DePaolo’s sixth place was lost in the noise of this great victory. The discerning, however, again took note. His turn would surely come.

“DePaolo’s sixth place was lost in the noise of a great victory”

Fate would bring it forward. The bricks of Indianapolis, high wooden bankings of boarded speedways, and deeply rutted dirt ovals – pounding, dizzying, jarring already – became even more unforgiving as speeds spiked while all other aspects of the sport struggled at best to keep pace with the new generation of lightweight single-seater. Boyer suffered fatal injuries at Pennsylvania’s Altoona in September – DePaolo was bedside when he succumbed. A fortnight later, Jimmy Murphy – another Indy winner, and rated the best of the bunch – was killed when a piece of fencing pierced his chest at Syracuse, New York. And Duesenberg’s Ernie Ansterburg would be killed practising at Charlotte, North Carolina, in October.

No12 again, this time at the Washington Baltimore Speedway six weeks after the 500 win

There were other, less grisly, costs. Duesenberg was the only mainstream manufacturer willing still to take on the specialist constructors, i.e. Miller. This expensive compunction had led to Fred and August’s losing control of the eponymous company, and to their beloved race shop being shunted over the road. Upstairs, too. There being no elevator, finished racing cars had to be eased down planks – once a brick wall had been removed.

DePaolo staked his claim to number one status with strong performances at California’s Culver City and Fresno, in March and April. His Duesenberg was generating 225bhp – but the majority of its rivals were by now supercharged, too. If there was to be an unfair advantage at this Indy, it lay elsewhere. One of the 16 Millers requiring to be beaten was breaking new ground.

Smooth-driving Murphy had pushed the premise that a front-wheel-drive car would better cope with tracks increasingly slicked by oil and rubber. Playboy/racer Cliff Durant, son of General Motors’ founder William Durant, paid for it – and Harry Miller decided to build a second, slightly different version for himself. Works driver Bennett ‘Nemo’ Hill hated the low-line machine, however, and pleaded for his usual RWD mount. Poor Murphy’s drive, meanwhile, went to Miller’s brother-in-law, Dave Lewis, who would start directly behind DePaolo.

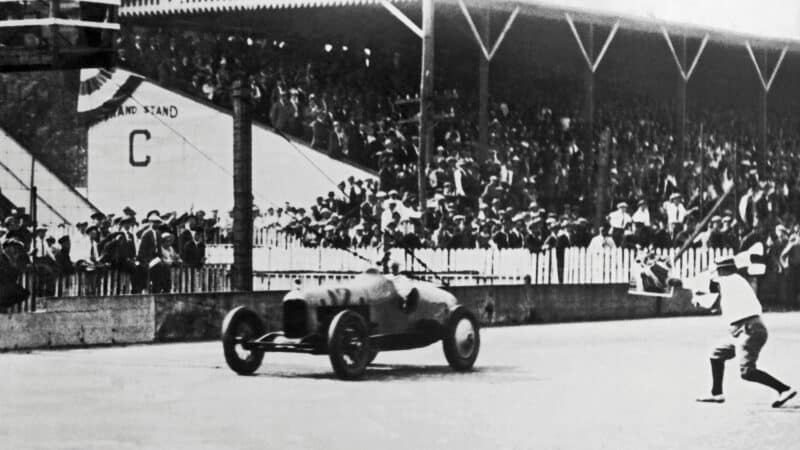

DePaolo, front row, centre, behind the pace car, 1925

Although the latter had set the fastest lap in qualifying – 114.255mph – he missed out on pole by 0.3sec over four. The 113.196mph of ‘Flying Frenchman’ Leon Duray – real name George Stewart, he was born in Cleveland, Ohio – represented a 5mph year-on-year increase. This was due not only to improved supercharging and blended alcohol fuels with better cooling and anti-detonation qualities, but also to Firestone’s new tyre. These low-pressure, gum-dipped ‘balloons’ – as opposed to high-pressure, straight-sided – with their steam-welded inner tubes, provided gains in handling, traction, comfort, wear and fuel mileage. Judging by the spate of early pitstops to alter their pressures and accompanying suspension settings, several – DePalma and Hill among them – had yet to get to grips with them.

“DePaulo would dominate at first – to the tune of $100 per lap”

DePaolo had no such worries. His problem was flooding and stalling the engine in his eagerness to begin the formation lap. Luckily, it had been agreed that the pace car – a Rickenbacker 8 driven by Eddie Rickenbacker – would run at no more than 60mph. And DePaolo reckoned that friendly Eddie had seen his problem and slowed some more – unlike the shrugging Oldfield’s Marmon of 1920! – enabling him to regain his place in the middle of the front row before the 22-car field was released at 10am.

Taking Turn 1 in second gear allowed him to nose ahead, a small advantage lost to a slow change into third, i.e. top. Determined to lead, however, he swept across Duray’s bows at the end of the back straight to complete the first lap at 103.87mph. DePaolo would dominate the first quarter – to the tune of $100 per lap – and, when finally a dot grew large in his mirror, he was told to slow by his crew. He was being caught by team-mate Phil ‘Red’ Shafer, who had qualified 1924’s winning car an unrepresentative last. DePaolo waved him through on lap 55, on the understanding that he slow down, for both of their sakes. In fact, their average increased – to 104.18mph after 70 laps – so perhaps they towed each other along.

The 1925 Indy 500 winner DePaolo, the first driver to complete the race in under five hours

Alamy

DePaolo reasserted himself after a dozen laps – for another, less amenable, dot was growing. Harry Hartz, a fellow riding mechanic-made-good, had started his Miller from the outside of the front row. Formidably consistent, he represented the greatest threat to Duesenberg. DePaolo braced himself for the fight – he very much wanted the watch that steel magnate Charles Schwab had put up for the leader at half-distance – and they passed and re-passed. Suddenly, it was over. Tyre trouble forced Hartz to pit after three laps in the lead. And another flat would have him brush the wall on lap 110. He finished fourth.

In contrast, DePaolo’s right-rear was changed as a precaution at his only scheduled stop, just past half-distance. Reckoned to be a charger, his set-up was clearly kinder than most. It was his hands that were shredded, due to vibrations transmitted by the steering wheel. Fred Duesenberg made a reluctant DePaolo see sense, and relief driver Norm Batten was plugged in so that DePaolo’s cuts and blisters could be tended to at the infield’s emergency hospital.

Bandaged prize fighter-style, DePaolo felt revitalised. Which was a good job. For Batten had slumped as low as fifth place during his 21 laps. Indeed, a great deal had changed in DePaolo’s enforced absence. Rookie Ralph Hepburn had pitted from the lead on lap 122 – he would retire 21 laps later because of a fuel tank issue – and Earl Cooper, yet to pit, had just this minute crashed from it. So Lewis was now out front – by more than a minute, from DePaolo. As Murphy had predicted, the FWD was coming on strong. Unlike its driver.

Although 1925 proved to be DePaolo’s sole win in the Indy 500, he’d return each year until 1930

Lewis pressed on for at least a dozen laps too many. When eventually he gave up his struggle on lap 172, tired brakes and muscles caused him to overshoot his pit. He was still leading one slow, enforced lap later – but DePaolo was poised to pounce. The latter’s cream/yellow-coloured Duesenberg, nicknamed The Banana Wagon, was more than a lap ahead by the time Lewis’s relief driver got up to speed. Hill, his FWD misgivings forgotten, and closing at 1.5sec per lap, drew alongside with a dozen laps remaining. The 145,000 crowd rose in response to his attempts to gee the leader into an unwise battle. DePaolo ignored one – and all.

He was still 53.69sec to the good when he took the chequer to complete the first 100mph Indy 500. His – and Batten’s – 4hr 56min 39.46sec equated to 101.127mph. DePaolo had led 115 laps, earning $36,150.

The enclosures were empty by the time he and Sally strolled through the main gate. They bought double chocolate malts at the drugstore on the corner of West 16th Street and Main – DePaolo had shed 11lb during the race – before continuing to their lodgings on West 15th. A reinvigorating shot of brandy and a reviving long, hot soak put DePaolo in good – tuneful and surprisingly deep – voice. Nessun dorma that night.