Empty Christmas Day roads and a Lotus 12 — the ultimate road test

Simon Clay

Christmas Day, 1957. Several men stand outside a pub watching a Ford Consul arrive, pulling a trailer with a small racing car on it. They’re conniving in an illegal act, and one of them will confess all in a magazine article. He is Denis Jenkinson, our continental correspondent, and shortly he will take this Lotus 12 on Hampshire thoroughfares… Now, on the eve of the auction sale of this historically significant machine, Gordon Cruickshank takes up the tale of chassis 353 and its role in Motor Sport’s legendary, festive ‘Figgy Pudding Grand Prix’

It’s a skimpy little thing, slim, short, low. Look at the photo of it arriving for its illegal excursion: the trailer that it’s perched on isn’t even full length. It seems nicely sized for DSJ, who wasn’t full length either. Yet it’s a historic design, the Lotus 12: Colin Chapman’s first single-seater, built for the new Formula 2 but shortly to be the rising Lotus outfit’s stop-gap debut entry into grands prix. Through the 1957 season the regular occupant of this one, chassis 353, is Graham Hill who has already contested F2 races in it, his first single-seater drives; in the coming year he’ll pilot it in the marque’s first Formula 1 event, a debut that confirms Chapman’s rising ambitions.

A works racer’s life being short it will soon be sold to privateers, then shipped to Australia. A fallow period follows; Lotus people know its significance but a restoration stalls for 27 years, until one man comes along who appreciates what it is. He’ll treat it to a full and loving restoration, doggedly compile its history and publish a comprehensive monograph about it.

Eventually the time will come when it has to move on, so it’s shipped back to the UK to show at a high-profile race meeting. Which is where we are today. After being on display at Goodwood Members’ Meeting, chassis 353 will be a star item in Bonhams’ sale at Monaco in May. But before eager buyers get to bid for this gem of mechanical history, this magazine wants to revisit the car that formed our illicit Christmas road test all those years ago. Let’s leave those men blowing on their hands outside the pub while others are sitting down to their festive lunch, and consider the metalwork.

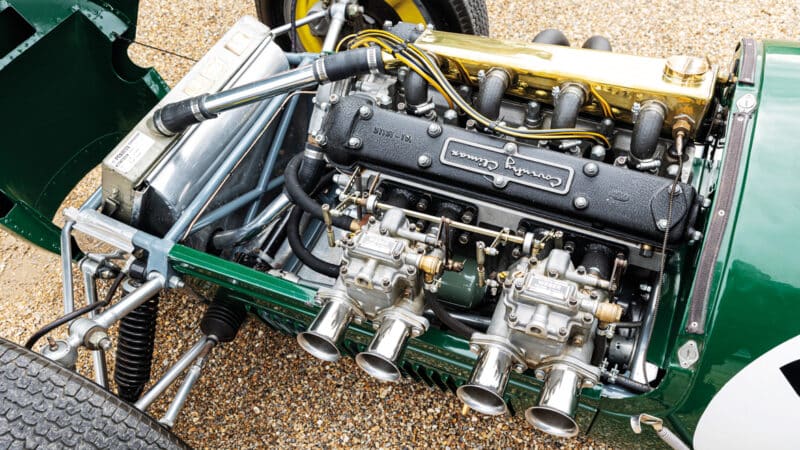

This being a 1956 design there’s naturally a tube frame braced with a riveted floorpan, though thanks to Chapman’s engineering knowledge it sticks to pure structural principles of triangulation, unlike Cooper’s chunky curved tubes. Power comes from Coventry-Climax, the FPF 1475cc four-cylinder perfect for the new 1.5-litre F2; the 141bhp twin-cam is still in the front – Chapman is content to let Cooper prove the rear-engine path while the 12 tries other innovations. There’s the Lotus founder’s novel suspension system using an upright spring strut and one radius rod to take fore and aft loads, the fixed-length driveshaft providing lateral location. Typical Chapman – make one component do the job of two.

Nothing to see here: the tiny Lotus 12 arrives behind Colin Chapman’s Consul for its illicit drive

LAT

Next, that crinkled yellow wheel, the famous wobbly web. Let’s not go into the structural analysis, but it’s a clever way of forming a lightweight alloy wheel. Then there’s that tiny five-speed gearbox in the transaxle, a handful of cogs so compact there’s no room for conventional selectors in between. Instead a tubular sleeve splined to the input shaft slides back and forth within the input gears which rotate freely on it, until the sleeve slots a dog clutch into the chosen pinion one after another, locking the shaft and sending torque to one of the drive pinions. That gives the driver a sequential change like a motorcycle box. When it works it works brilliantly. When it works…

Light, lithe and nimble, the 12 displayed Chapman’s drive for low frontal area – the driver sat low in the tight cockpit and the radiator leaned back for a lower, sleeker nose profile. It was an elegant offering and competitive, setting fastest laps; it just didn’t win. Repeated mechanical failures, often around the gearbox and driveline, snatched away promise from Hill and team leader Cliff Allison through 1957, first year of the new F2 series, though the cars did grow more reliable through ’58.

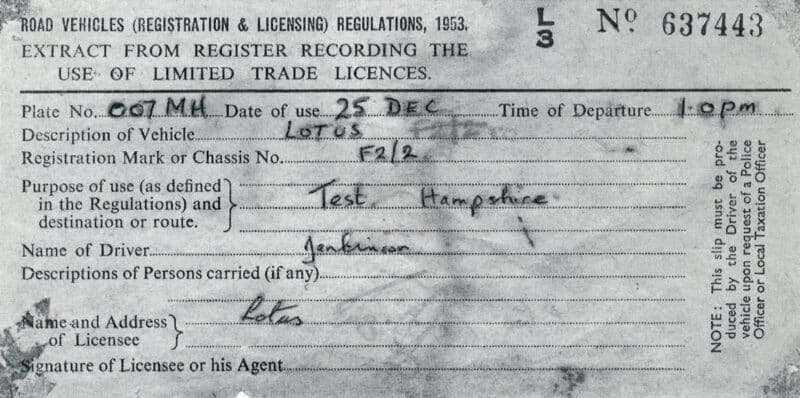

“It’s OK, officer, I have the paperwork” – Chapman filled in a trade plate form for the F2 car, just in case not all the police were at their Christmas lunch

Motor Sport

That engine grew too. Formula 1 ran to 2.5 litres in 1958 and that was where Chapman wanted to be – displaying his design brilliance on an international stage. Having already assisted Vanwall to refine its own chassis he was now focused on his full GP contender, the Type 16, but that wasn’t ready for the start of the ’58 season. However, there was still a way to plant his standard in the field. Back then F2 machines could run in F1 events and while Climax couldn’t yet stretch the FPF a whole extra litre they could offer Lotus a 1960cc version. Yes, they’d give away power but on a tight track the nimble green device might capitalise on its fine handling.

Thus on May 3, 1958 the Daily Express International Trophy included works Lotus 12 entries for Hill and Allison. Yorkshireman Cliff’s car ran in F2 while Hill’s usual 353 had the bigger engine – a little more power, a lot more opposition: BRM, Moss in a Cooper, Maserati, even a lone works Ferrari Dino for Peter Collins. Though Silverstone is hardly the tight circuit the compact Lotus craved, Hill climbed as high as fourth before being hobbled to seventh by fuel starvation. Allison topped the F2s finishing sixth overall. An unspectacular result, yet a significant day – Lotus was on its way.

Graham Hill in 353, Monaco, 1958, with Chapman on right (in shades

Getty Images

The Lotus is auctioned at Bonhams’ The Monaco Sale, May 10

Bernard Cahier

Positive-stop modification improved the ‘queerbox’ action

Bernard Cahier

“No one imagined Hill would go on to take five victories on the principality’s twisting roads”

A fortnight later both cars, equipped with the larger engines, travelled to Monaco for the marque’s grand prix debut, qualifying midfield; Alison placed sixth and last, but Hill broke a half shaft. Still, he was running fourth at the time. No one imagined he would go on to take a remarkable five victories on the principality’s twisting roads, or that the 12 was launching a glittering marque career that would bring Lotus seven constructors’ championships…

Hill relied on 353 for two more GPs, the Dutch and Belgian, before switching to the 16. At Spa, Allison would post the car’s best GP result with a fighting fourth – but the three cars ahead all suffered terminal maladies around the finish line. If there had been 25 laps, not 24…

In truth, despite some impressive performances, the tiny 12 was not especially successful, multiple breakages giving birth to that Lotus reputation for speed with frailty. Yet our car, 353, remains pivotal to Lotus history: the first single-seater, the first grand prix entry and of course that festive road test.

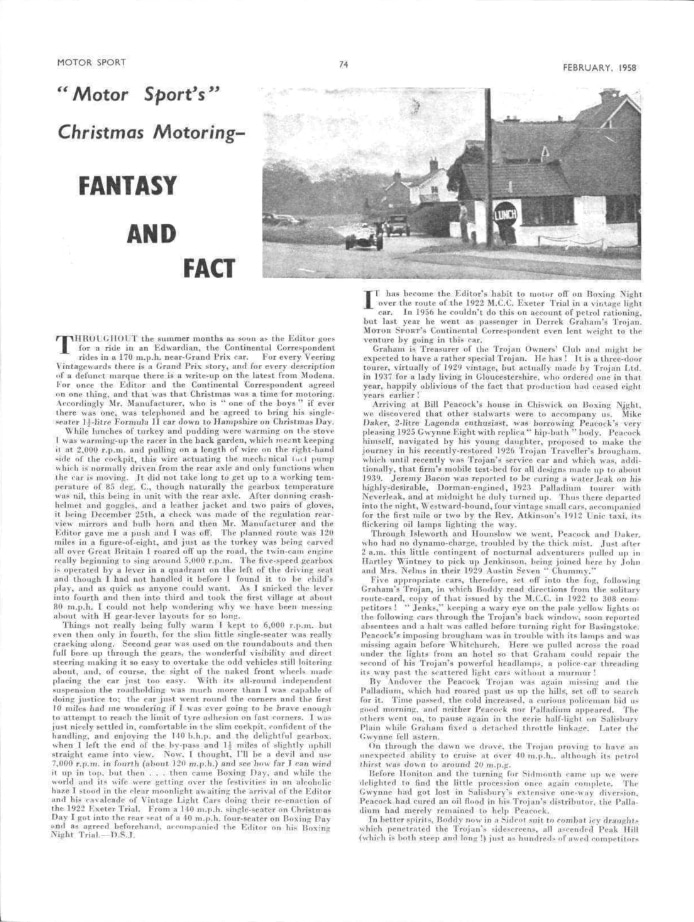

Fantasy and fact: Jenks’ account of his drive in our February 1958 issue (find it online in the Motor Sport archives) was cagily economical with the facts, not mentioning any speeds: “It being December 25th, a check was made of the regulation rear-view mirrors and bulb horn and then Mr Manufacturer and the Editor gave me a push and I was off.”

Motor Sport

That’s why in 1991 Australian Lotus enthusiast Mike Bennett rescued it from 27 years of inaction. At the end of 1958 Lotus sold it, with a 1500 FPF; Bruce Halford, Henry Taylor and Maria Teresa de Filippis all drove it before Aussie racer Frank Gardner took it on, and in 1961 his associate Len Deaton shipped it to Australia. There it changed hands several times, being restored in 1966 by David Conlon and running in varied club events. “But,” says Bennett, “the previous owners told me they ran it until it wouldn’t go anymore. Turned out they’d stripped the crown wheel and pinion.” These special ZF units being long unavailable, the car sat, not unloved, just immobile, until Mike and his mate Don Asser saw its last-minute entry to an auction. ”We made a few phone calls and pounced. By then word had got around but it was too late.”

Remarkably, the car had come through almost complete – in Mike’s words, “only lightly messed with”. There were the FPF Lotus sold it with, the 1957 wheels, panels with ‘No2’ punched in (Allison’s was No1); it even had retained the trick gearbox. “Once Keith Duckworth had modified the lubrication it became reliable. It just has to be perfectly set up, and I love that sort of stuff,” says Mike, an engineer by training who tackled most of the restoration himself, including the gearbox. He also embarked on a serious research quest, travelling around the UK and Canada to speak to everyone he could who was associated with Lotus 12s and tracking down every known photo.

Several things came out of that intense effort: the pitch-perfect return of the car to its 1958 form, a comprehensive book on the car, titled Lotus 12 – Chassis 353, and his becoming Lotus 12 registrar, with huge files on every chassis history. It’s clear from the book and Mike’s painstaking restoration records that he brims with determination and dedication. Deciding the car should not be raced seriously again Mike instead has displayed it at many Australian events, and in 2012 brought it over to the Goodwood Festival for the Lotus 60th.

Larger 2-litre Climax FPF gave 12 its F1 world championship debut

Getty Images

“You could see Frank’s eyes drifting into the past and he said, ‘I’ll always remember this one’”

Speaking today, Mike recalls a touching moment when at one gathering he reunited Frank Gardner with the car. “You could see his eyes drifting into the past and he said, ‘I must have driven 150 cars but I’ll always remember this one – my first single seater.’”

But it must be cold for those chaps waiting on that December day so let’s return to the Phoenix pub. Bill Boddy has arrived from his nearby home in an Austin A105 he’s trying out for Motor Sport, and there’s also Alan Southon, whose car workshop beside the pub, now Phoenix Green Garage, remains a vintage car honeypot today. Actually this was nearly a Vanwall trip, until the Maidenhead team realised the possible PR knockback, so Jenks decided to call Lotus. Chapman, he declared, was “one of the boys” and sure enough ‘ACBC’ came up trumps. He wasn’t ready with an F1 car, but DSJ could certainly have one of the works F2 machines. He would even bring it over from Hornsey himself.

Chassis 353 has spent much of its existence in Australia, where it was restored to full 1958 working order

Simon Clay

Graham Hill at the 1958 Monaco GP in the Lotus 12

Getty Images

After the 1958 season 353 was refitted with a 1.5-litre FPF, which it still has

Simon Clay

With Chapman is team mechanic Merv Therriault, who unloads the car and warms it up while Jenks borrows WB’s Austin to do a quick check of his route, a 180-mile figure of eight round Hampshire he normally used at 2am to test fast cars. In 2001 Merv recalled, “this tiny man, Jenks, wearing two or three coats and his feet bound in sacking for warmth, held in with farm twine…” Our continental correspondent never worried about appearances.

“You’d better borrow our trade plates, they might soften the blow if you get stopped”

Writing the day up in the BRDC bulletin (a franker account than the guarded one in Motor Sport) DSJ recalled, “While he ‘fitted’ me into the narrow cockpit, Colin said: ‘You’d better borrow our trade plates, they might soften the blow if you get stopped.’ The question of an open exhaust, no mudguards, no audible warning of approach, a racing car on the road, undue speed, and anything else the law could think up, we reckoned would tot up to a pretty hefty fine, but with a bit of Christmas spirit would not involve a jail sentence.” Back then that was a joke; today prison would be a certainty.

Double debut: Hill was running fourth in his first F1 World Championship race when a broken half-shaft on 353 forced his retirement from the team’s first GP

Getty Images

Very sensibly for the company MD Chapman wishes him luck and disappears home while Jenks dons helmet and gloves, Merv pushes him off onto the road and Bill Boddy stands across the way to record the moment with his Rolleiflex. There’s only time for one moving photo – of the car not quite on the public right of way – before he heads off for his Christmas lunch. Amusingly, when Mike tracks down WB’s few negatives of the day he notes, “None of them show faces – they didn’t want evidence recorded!”

When you read the next part of Jenks’ memories, remember that in 1957 there were no 60mph or 70mph limits – technically there was no absolute limit at all. Now read on, filled with envy for times past.

Simon Clay

Simon Clay

“I wound the Lotus up to about 120mph in fourth gear and snicked into top”

“The little Lotus was a revelation on the open road and hummed along at 80-90mph on the first section of the route which involved a bypass and some roundabouts. Out beyond Basingstoke, heading for the open plains, I wound the Lotus up to about 120mph in fourth gear, snicked into top and was just getting ready to reach its terminal speed when the revs shot up and there was no drive to the wheels.”

A driveshaft has broken, due to being incorrectly fitted. Still freewheeling, Jenks turns into a convenient driveway and coasts to a stop to ask if he can use the phone. In a letter to Mike Bennett, WB recalls being at the “pudding and crackers” stage when the call came and he rushed off to assist.

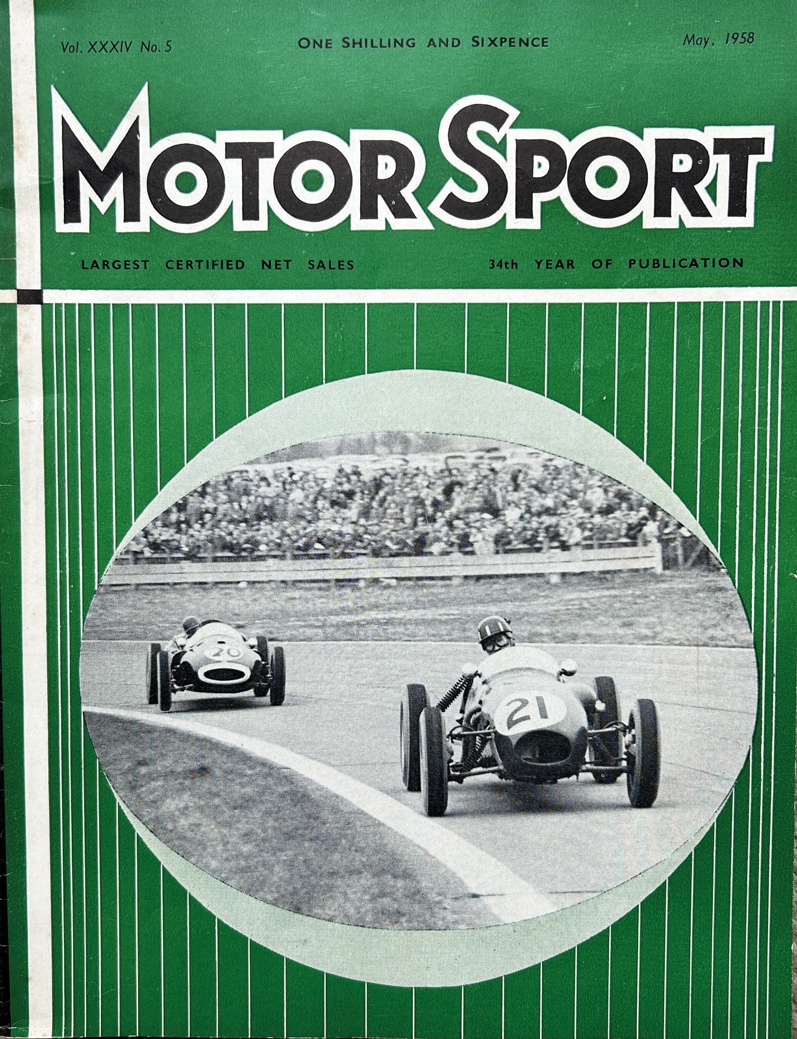

“A duel that enlivened The Goodwood Easter meeting…” we said in May 1958. Hill in 353 leads Brabham’s Cooper

Motor Sport

Jenks made a typically brusque entry in his diary: “Drove F2 Lotus off at 1pm. Broke transmission beyond Basingstoke. Alan collected me in HE. Bod came and towed Lotus in with A105.”

Only 30 miles of Hampshire roads had passed under the Lotus wheels, but DSJ had achieved his aim of driving a grand prix car on the road. And he wasn’t arrested, despite parading his guilt in Motor Sport.

Mike is sanguine about selling. “I’ve had 33 years of pleasure from it, particularly the mechanicking. I’ve travelled the world following up on 12s – at least there’s one thing I’m the world authority on!”

Did he consider taking it for a drive through the Adelaide Hills? He laughs, but says if a bushfire had threatened he would have jumped in it and driven it to the nearest underground car park with sprinklers.

Well, it’s safe from that fate now. If you happen to be going to Monaco for the sale, stop and admire this little car. Spindly it may look, but every little tube of it is packed with significance, for Chapman, for Hill and for Lotus. And, of course, for Motor Sport.