‘The best of times’: Adrian Reynard relives F3000 era in Alesi’s ‘89 title-winner

Jean Alesi made his name in this Eddie Jordan-run F3000. Now the man who put his name to the car, Adrian Reynard, has driven it for the first time. Damien Smith reports

Jayson Fong

Reynard in a Reynard? This we’ve got to see. Especially as the car in question is peak Formula 3000, the long-defunct Formula 1 feeder that roamed Europe as a gloriously open chassis and engine category between 1985 and ’95 before the dreaded one-make malaise set in. Company founder Adrian Reynard, in Jean Alesi’s Eddie Jordan Racing, Camel-liveried, 1989 championship-winning 89D at Donington Park? Yes! please.

Jean Alesi’s first F3000 win of 1989 came here in the Pau GP – weeks before his F1 debut

DPPI

Reynard’s logo naturally had to be a fox – perhaps adding some wiliness to the drivers’ skills

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Bicester, England – the company’s base before it moved to Brackley

Jayson Fong

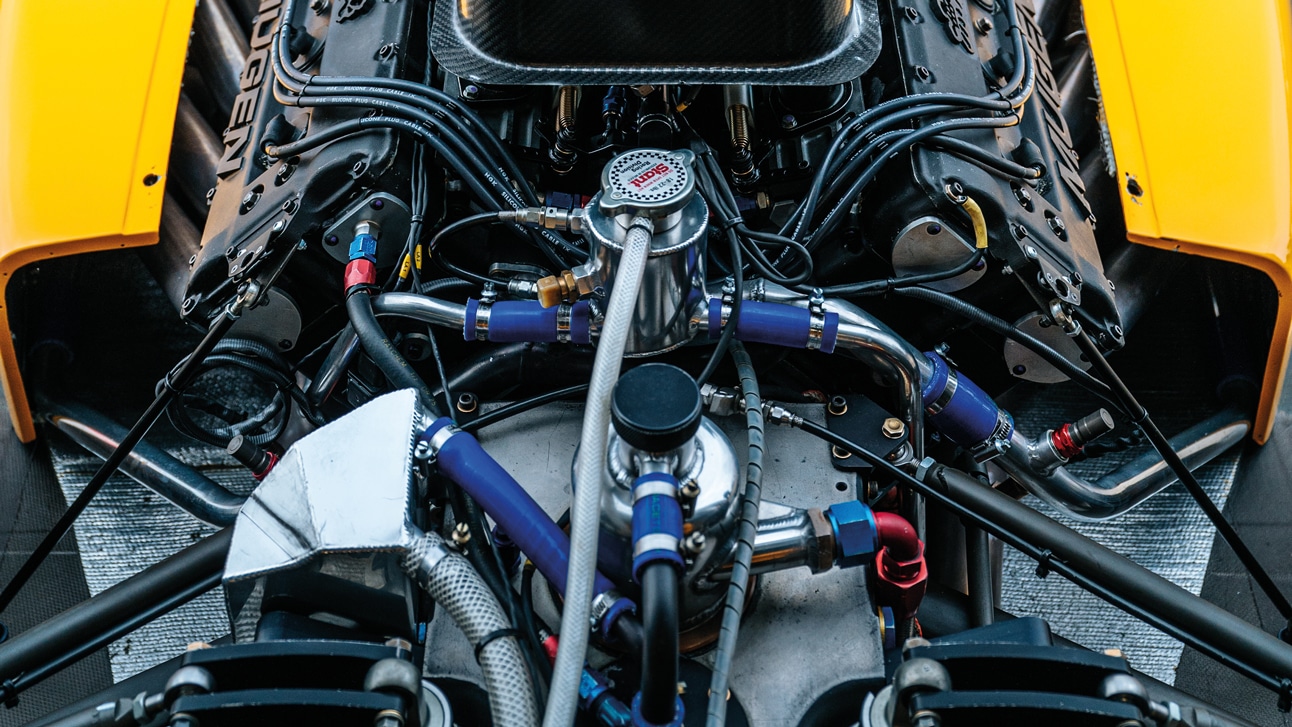

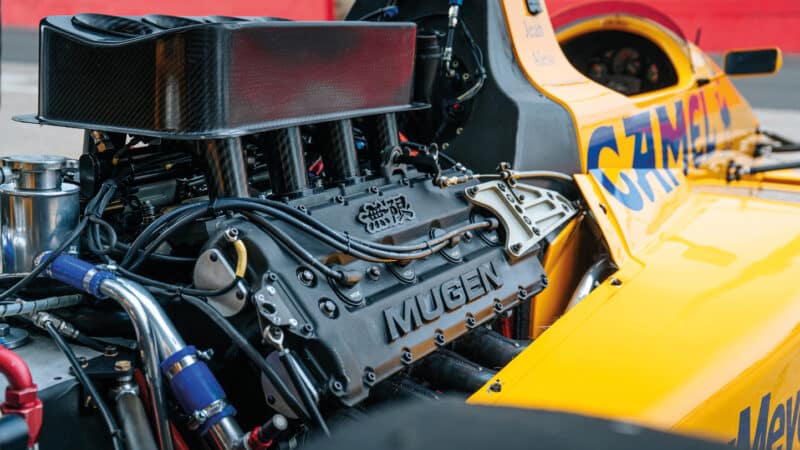

Eddie Jordan’s 89Ds in 1989 were powered by a Mugen 3-litre V8

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

“I’ve never driven an F3000 car or anything bigger than a Formula Atlantic,” says Adrian with a hint of out-of-character nerves. He’s 73 now, but looks great on it and is preparing to indulge in another season driving one of his own Formula Ford 2000s in the well-supported Historic Sports Car Club series. “I’ve actually built a brand new old-stock FF2000 for this season,” he says, “a 1981 car. Brand new chassis built to my drawings which I found. Ken Thorogood built it for me in Norfolk. It’s almost ready.”

So is the vibrant yellow F3000, which is brightening a dull East Midlands day. That 3-litre Mugen V8 cuts a crisp note too as it warms in the pitlane. They’ve aged well, this generation of single-seater that pitched Reynard against long-established March and Lola, with an added dose of Ralt and (briefly) Dallara, along with a bevy of independent engine tuners before one-make control became de rigueur. It’s a cold day, and this old-school analogue beast looks ready to bite, on a filming day organised by Adrian’s son Sam, who is making a documentary about his father’s company and its place in the wider motor sport story. Adrian promises caution. Probably wise.

Incredibly, Adrian Reynard had never driven one of his own F3000 cars – until now, at Donington

Jayson Fong

Bruce McLaren was the initial inspiration. But by the early 1980s and in the wake of a 1979 European EFDA FF2000 title, Adrian Reynard dropped his racing driver aspirations. “I thought I’m either going to progress my career in the cockpit, which meant building an F3 car for myself, or I’m going to run the company,” he recalls. “I couldn’t afford to build an F3 car so I abandoned my driving career. I never drove anything after that.”

Reynard had a phenomenal 1980s, by any measure. Adrian credits hard lessons learnt during his motorcycle speed record antics at Elvington airfield in the early 1970s for his template approach to designing and selling production racing cars. The benchmark in FF1600 and FF2000 from 1982, Andy Wallace won on Reynard’s F3 debut in 1985, then stormed to the first F3 title the following year, with Johnny Herbert and JJ Lehto completing a hat-trick. Adrian was canny, loaning cars to top teams Madgwick, Eddie Jordan Racing and Pacific rather than making them pay, to ensure the best drivers sat in Reynard’s carbon-fibre tubs. When they won championships that’s why he could claim the cars back for posterity.

Roberto Moreno, engineer Gary Anderson and Bromley Motorsport kept up a debut win tradition in 1988 when Reynard stepped up to F3000. Then EJR, bruised by Herbert’s terrible foot-mangling crash at Brands Hatch, hired French-Sicilian Alesi for 1989.

“The F3000 was the last car I had an intimate design input on,” says Adrian. “I had hired Malcolm Oastler a year or so before, tasked him with redesigning the FFord for 1987 which was a really good car. I laid out the first 88D, chose an ultra-long wheelbase, longer than anybody else, with a carbon chassis which was still novel. I used quite a few bits from the F3: the steering wheel and column, the pedals. I like common parts. I laid out the radiator system, did some aerodynamic work, chose the gearbox. It was very much my car, but I handed over the design concept to Malcolm and he finished it off.”

Reynard lured Anderson to join for 1989, impressed by revisions the Northern Irishman had brought to the Bromley car. “When we got it there were lots of things I didn’t consider to be correct,” says Anderson. “The rear top wishbones would bend very easily if you hit a kerb, the front anti-rollbar system didn’t really work. So I redesigned them for the Bromley car. Aerodynamic tweaks around the rear tyres, a slightly different front wing flap and endplate arrangement. Those things allowed me to express myself on the 1988 car with Roberto. Reynard as a company followed suit and Malcolm incorporated them in the 1989 car, then Adrian asked me to work for him.”

“It was well-refined. It made a big statement in F3000 and is one of my favourite cars”

Reynard describes the 89D as “an improved version” of its predecessor. “At that stage I had also hired a young school leaver, Andrew Green. We also had a chap called Mark Smith, and they were all involved in the F3000 project during that year. But the 89D was really Malcolm’s car. Andrew, Mark and Gary all went on to become F1 technical directors, so a pretty strong team. It was a well-refined car with improved efficiency and better reliability. It made a big statement in F3000 and is one of my favourite cars.”

That 1989 season was a classic year for F3000, pitching EJR’s Alesi and Martin Donnelly against the DAMS Lolas of French F3 champion Érik Comas and Éric Bernard. Others to play cameos included Mark Blundell and Damon Hill, while Swede Thomas Danielsson was a surprise Round 1 winner at Silverstone (in a Madgwick-run Reynard) and Swiss Andrea Chiesa an early title contender for Roni Motorsport. Chiesa won at Enna, but only after Donnelly had skittled team-mate Alesi off at the first turn on a track surface chewing up in “local temperatures running on a par with an Australian test score”, as Motor Sport’s report put it.

Donnelly put that blot behind him to beat Alesi at Brands, before Jean held off Marco Apicella’s First Racing Reynard in a close-fought Birmingham Superprix, completing a street race double in the wake of his early season win at Pau. Another victory at Spa strengthened Alesi’s grip, with sixth on the Le Mans Bugatti circuit sealing the deal. Comas grabbed a home win and another one at Dijon to finish equal on points with an absent Alesi, who by now was the new darling of F1. He, Donnelly and Bernard had all made their GP debuts at Paul Ricard between the Jerez and Enna rounds for Tyrrell, Arrows and Larrousse respectively, Alesi making the biggest splash with a fourth place. The F3000 title, won on Alesi’s three wins to Comas’s two, only confirmed his Jean-come-lately status.

Another F3000 win for Alesi, this time in the sunshine of the Birmingham Superprix

Getty Images

But back at Reynard as the year turned, Adrian was fuming. “Andrew, Mark and Gary were all poached by Eddie Jordan and that destroyed my F3000 design team,” he says. “We lost the championship to Lola [Comas completing what he started with DAMS] in 1990 as a result. I didn’t speak to Eddie for years, nor any of those people. I was so upset. But I’m good friends with them all now.”

Jordan, of course, was plotting his way to F1 and what turned out to be that unforgettable maiden campaign with Anderson’s gorgeous 7 Up-green 191. “One of the reasons [I left] was I did have a fairly heavy discussion with Adrian on front suspension geometry,” says Anderson, who admits the compromises of production car design were a frustration. “In the end the car got the new parts I wanted but it wasn’t easy. I felt the battle is hard enough to build a good car without battling with the people you are working for. Adrian got the hump a bit. When I was there we did a transverse gearbox for the 1990 car. It was very easy with a transverse ’box to get two gears at the same time, so I came up with this interlock system which stopped that happening. Adrian got a bit legalese with me taking this design to Jordan because I designed it on Reynard’s time. It all fizzled out later on.” Indeed, so much so that Anderson returned to Reynard to work on its IndyCar programme in 2001.

Alesi in Birmingham; he’d win the next race too at Spa and the F3000 title was his

Getty Images

In 1991, as Jordan slayed giants, Reynard plotted his own ascent to F1 with a car designed by a crack team of disaffected former Benetton engineers led by Rory Byrne and Pat Symonds – only for an old Reynard weak spot to scupper the plan.

“I was pretty confident my company could design and build an F1 car,” says Adrian. “The problem is we’d never developed the commercial side to get the sponsorship. We had a good car, but I didn’t really get an engine deal. I could have had one with Yamaha, but Rory wasn’t impressed. It was hopeless and I had to let the project go. It almost bankrupted me.”

“I did derive some satisfaction that the Benetton B192 was such a successful car”

The Reynard became the Benetton B192 (and also the 1994 Pacific PR01!) as Byrne, Symonds and co returned to their former team in the wake of John Barnard’s departure and the arrival of Tom Walkinshaw and Ross Brawn. Michael Schumacher won his first grand prix at Spa in August ’92, with F1’s growing force moving into a new rural factory near Enstone, Oxfordshire that winter. The factory and the land it was built on had been Reynard’s too. “I did derive some satisfaction that the B192 was such a successful car,” says Adrian, without bitterness. “I’m not claiming any credit for it, but we had been on the right track. And yes, I designed the Enstone factory with Guy Austin, who became a good friend. I had to sell it to Walkinshaw because again I didn’t have the commercial side to push it through.

Jayson Fong

Jayson Fong

“Later I moved my Bicester factory to Brackley and Guy helped me design that unit, which has also stood the test of time.” That’s the base from which BAR was born, which begat the works Honda team, which begat Brawn, which begat Mercedes.

In 1994 Reynard turned from F1 to making its most significant mark in IndyCar, Michael Andretti keeping up the debut win record in a Chip Ganassi-run entry at Surfers Paradise. Again, Reynard felt the lure of F1 with the BAR project, which conspicuously failed to keep the debut win run going in 1999. Adrian’s mainstream motor sport story came to an abrupt and sad end in 2002 when a cocktail of bad luck in a volatile post-9/11 economic climate, a changing one-make motor sport landscape and perhaps that old commercial blind spot brought his company to bankruptcy.

But his fingerprints are everywhere in motor racing, and today his board advisory roles at alma mater Oxford Brookes and Cranfield universities mean he’s still playing a role in nurturing the next generation of engineers. Meanwhile, Adrian’s new-old FF2000 and a lingering fascination with motorcycle speed records keep him diverted down his well-trodden motor sport path.

“I really enjoyed it. Donington is probably my favourite circuit anyway”

The runs in Alesi’s title winner were short, sweet and now complete. Son Sam has shots in the can for the doc and Adrian can reflect on his first experience in one of his own classic F3000 creations. “I was right to be worried about cold tyres,” he says. “Although they’d been in tyre warmers by the time you got to the end of the pitlane the tyres were cold and anyway I wasn’t going to hurl it around to get much heat into them. But I fitted the cockpit very well, it was very comfortable and I got out of the pitlane without stalling too much! And I really enjoyed it. Donington is probably my favourite circuit anyway. On my last lap I out-braked myself into the chicane and thought, ‘that’s enough!’”

Reynard 89D chassis 017 has taken Adrian back to what, with hindsight, were the best of times. “I really enjoyed having the team of Rick [Gorne] and Malcolm with me,” he says. “We had a fantastic bunch of really good people who knew really good things. Rick was the best racing car salesman ever. He was so proud of what we were doing it was easy for him to sell because he really believed in our product. He didn’t let people go. And Malcolm I loved because he is such an intuitive engineer, far more capable than I was. Not only that, he was a great leader of people. The team and the customers loved him. Everything was going well in the ’80s.”

“We had a fantastic bunch of really good people who knew really good things”

The parallels to Jordan – his old friend, customer, adversary and now friend once again – were always there. “I bought a house in the early 1980s and Eddie and his wife Marie sat on the floor because I didn’t have any furniture, and they didn’t have anywhere to live. That’s where we both came from. We were people determined to be successful in motor sport. Both of us gave up driving careers, so we had that in common too. Eddie ventured out more on the sponsorship side. He wasn’t technical but he had a great personality. Although sometimes it annoyed me, especially when he nicked all my best staff.”

None of it could happen today. “I don’t know how a new person could do what Colin Chapman, Eric Broadley, Ron Tauranac and myself have done,” rues Adrian. “There are very few free formulae left. It’s all one-make. You are going to have to compete with Dallara and Tatuus, and you can’t guarantee prices for a three-year contract if you’re not established. Also it’s very sad that proper engineering has gone out of it. It’s more like driver coaching now. They look at the data, work out where to go 1mph faster here, more steering lock there. It’s not the same.”

Modern F2? Comparisons are futile. Today might as well be a different world. Thirty-plus years ago, Adrian Reynard and his plucky band had the best of it.

Reynard 89D chassis 017

Chassis: Carbon-fibre composite monocoque

Engine: Mugen MF308 3-litre V8

Power: 490bhp (F3000 rev limit of 9000rpm)

Transmission: Reynard longitudinal five-speed gearbox with Hewland internals(FT/FG)

Suspension: Pushrod/ Koni dampers

Weight: 540kg

Tyres/wheels: Avon tyres and Tecnomagnesio wheels

Our thanks to MotorSport Vision, Colin Sowter, Nick Edginton and Adrian and Sam Reynard for making this feature possible.