The 'frightening' Israel Grand Prix that drivers abandoned and fled

“The danger aspect was appalling. It should never have taken place”: one damning assessment of the first attempt to run an international race in Israel. Mark Bissett tells the story of what became a disaster in the desert

An international F2 race was the bold plan. In the event, a chaotic supporting Formula Vee event was a portent…

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Motor racing oddballs can really liven up our sport’s history, and the Formula 2 Israel Grand Prix is right up there. Held in November 1970 on the Mediterranean streets of Ashkelon – an ancient seaport city 46 miles west of Jerusalem – it brought its own sort of conflict.

The event came immediately after the 1967-1970 War of Attrition between Egypt, Israel, Jordan and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) in which the Egyptians attempted to regain the Sinai Peninsula lost to Israel in the 1967 Six Day War. When a ceasefire took place in August 1970, the frontiers hadn’t changed.

Alcohol is behind many interesting ideas and this was one. Wolfgang Diemer and Ingo Trepel were businessmen from Mainz and Wiesbaden with interests in Israel. Over a few frothies at the bar they came up with a concept for a race in Israel that would take place during the European off-season. It was a clever thought. Israel was growing rapidly with a wealthy young population, and had no motor sport to speak of. Here was a chance to get in on the ground floor.

There were to be no winners on the day after police and marshals lost control

Jutta Fausel-Ward

The Germans had complementary skills. Industrialist Trepel had relationships within Israeli politics, while Diemer was a publicist and sports-marketing firm owner and a vice-president of the Automobile Club AvD (Automobile Club of Germany).

They incorporated the Israel Racing Association to hold their event ownership rights. The race programme comprised an F2 grand prix, with Formula Vee and touring car supports. Fifty drivers were expected.

The promoter, and the organiser, the Automobile & Touring Club of Israel, saw the opportunity for an annual meeting to plug the gap created by the demise of the Bahamas Speed Week. “This might be filled by Ashkelon with its mild winter climate, lovely beach and charming hotels… an excellent base for journeys to the Negev Desert and The Dead Sea,” The Chronicle reported.

A part-completed housing development at Barnea Beach provided a venue, a circuit comprising two-and-a-half miles of narrow, bumpy roads in a barren area among sandy fields, dunes and wild vegetation.

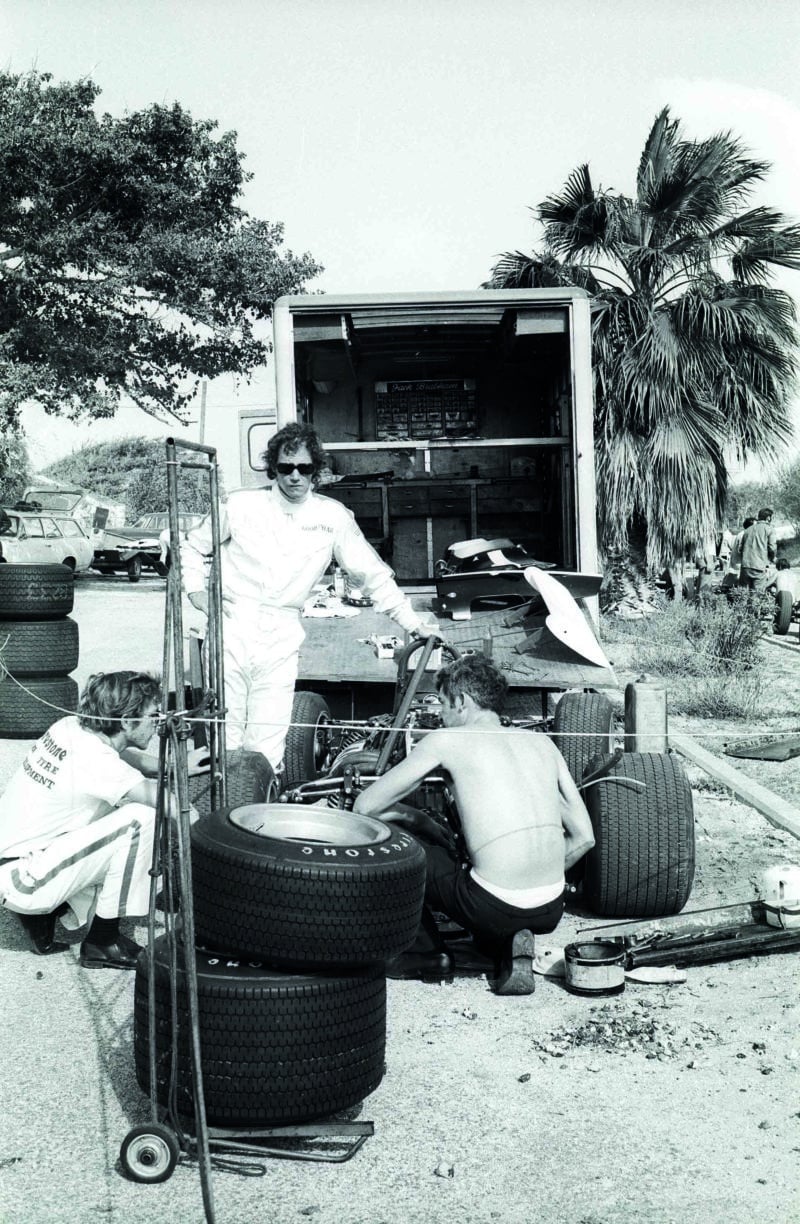

Ala d’Oro team brought Brabhams for Brambilla brothers

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Given the promise of tourists and local entertainment to a restless populace, the event was approved by Israel prime minister Golda Meir’s government. Politically it was good news, and the Ministry of Tourism and the local municipality gave financial support.

Given Diemer and Trepel’s very good knowledge of Israel, and the involvement of the government, the choice of Saturday, November 21, the Sabbath, as race day is beyond comprehension, an error of staggering proportions which put the business venture at risk from the start.

Israel had no culture of motor racing. The event was “the first car race in the history of Israel. Special courses will train young Israelis as racing drivers. It is expected this training will contribute to increased safety on the roads,” said The Chronicle.

Devoid of any racing infrastructure, everything required was brought into Israel, including officials. Diemer involved the AvD and the Wiesbaden Automobile Club: 25 of their members provided marshalling, management and scrutineering skills, and trained the locals to make future events sustainable. The race director was Gerd Kroeber, and stewards of the meeting were Diemer, Porsche’s Huschke von Hanstein and local man Bruce Jacobson.

Practice grid shows track was barely wide enough for two F2 cars, with unmade edges

Jutta Fausel-Ward

The 1970 European F2 Championship was a close-fought affair. Clay Regazzoni won the title in a Tecno 69/70 powered by the ubiquitous Cosworth 1.6-litre FVA engine. Derek Bell was second in Tom Wheatcroft’s Brabham BT30 with Emerson Fittipaldi third in a Lotus 69. The final F2 race of the season was on October 11, while the last Formula 1 grand prix was in Mexico City on October 25. The timing of the Israel meeting was good, with plenty of global talent available.

That Mexican GP, won by Jacky Ickx’s Ferrari 312B, was a disaster of crowd control. Only driver restraint ensured the worst didn’t happen. By the standards of Ashkelon, however, Mexico City would look like a Sunday school picnic of good behaviour.

The F2 entry comprised Brabham BT30s for Derek Bell, Vittorio and Ernesto Brambilla, Tommy Reid, Peter Westbury and Mike Goth. Brian Cullen entered an older BT23C and Patrick Dal Bo had a works Pygmée MDB15. Patrick Depailler was aboard a works Tecno 70, Bruno Frey in a Tecno 69 and Xavier Perrot a March 702; all were FVA-powered. The entry wasn’t the best of the year but had more than enough talent and chassis variety to put on a great show.

The Formula Vee field was remarkable for its depth. Brian Henton, Bertil Roos, Helmuth Koinigg and Harald Ertl all graduated to F1; Henton won the 1980 European F2 Championship. A hard-fought Vee scrap was guaranteed. And there would be a touring car race for local drivers.

German photographer Jutta Fausel-Ward attended the meeting. “The cars were transported to Turin and then shipped from Genoa to Ashdod,” she recalls. “The four-day voyage was loads of fun. There were the racing cars and all the stuff that was needed for the race; 25 organisers, marshals and a pistachio-green Lamborghini pace car.”

Most of the visitors stayed at the Schechter and Seminar hotels in Ashkelon, overlooking the sea. “A good time was had by all with plenty of time for some local sightseeing,” Jutta says.

While sand blowing around Barnea Beach roads created havoc, the real storm was the plan to race on the Sabbath, the seventh day of the week to religious Jews, and Judaism’s day of rest.

A national uproar arose through the Israeli press and resulted in impassioned speeches of protest in the Knesset – the state’s legislature. “A few days before the event the protests of devout Jewry reached such an extent that the German organisers shifted race day to Sunday,” it was reported at the time. But the event was doomed. The ‘any publicity is good publicity’ adage didn’t hold. For every Israeli who wanted to be a spectator, there was a devout Jew intent on disrupting the show.

Whatever their religious inclination, the Israeli spectators shared with those Mexicans a complete lack of understanding of the dangers of high-speed racing cars, of where it was and was not safe to stand. It was this crazy machismo attitude that would cause the grand prix’s abandonment.

Conditions in the temporary paddock were basic, with no facilities or shade from the sun

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Practice commenced on Friday at 10am when the F2 grid took to the circuit to look at the layout and assess gear ratios and mechanical and aerodynamic settings.

“The roads were laid out but no buildings, no boundaries, just ropes,” says Cullen. Derek Bell recalls, “just sand dunes, like Zandvoort. No barriers – you just turned left at the next mound of sand. And when a car went to the circuit edge it threw sand all over the track.”

American racer Mike Goth was quickest from Perrot and Depailler’s works Tecno.

The local touring car first session ended in mayhem. The drivers, with little or no experience, had accidents in bulk, resulting in red flags. At midday the Vees went out, their session interrupted several times due to the proximity of the crowd to the asphalt.

Aftermath: the saloon race for local drivers, despite “special courses” of training, was red-flagged several times

Jutta Fausel-Ward

“The track was closed at 2pm, with no on-circuit activity on Saturday, the Sabbath,” Jutta recalls. “The organisers bussed-in the drivers and support crew into Jerusalem for the day to keep us occupied.” Cullen, though, made his own entertainment. “I spent the day on the beach with a beautiful lady I had met,” he laughs.

A race-day crowd of over 20,000 spectators was a spectacular result. The citizens of Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and other population centres close to the Barnea Beach circuit poured in, but the organisers were unable to cope. There were far too few marshals, the venue wasn’t secure, most spectators didn’t pay to enter and had no sense of danger. Safety zones were ignored. The further forward the spectators edged trackside, the better their prevailing mood.

“They were 20 or 30 deep on each side,” says Cullen. “They would stand on the track and only move back when the cars arrived.”

Patrick Depailler placed second on the grid in the works Tecno, hired for the event by Elf.

Jutta Fausel-Ward

The F2 cars took to the track for final practice and qualifying at 10am, pole going to Ernesto ‘Tino’ Brambilla’s Brabham BT30 on 1min 23.8sec from Depailler, Bell, Goth, Perrot, Westbury, Dal Bo, Cullen, Vittorio Brambilla, Reid and Frey.

The local touring cars practiced with the same crowd problems as on the Friday.

“The saloon race was frightening,” says Cullen, recalling the multiple incidents.

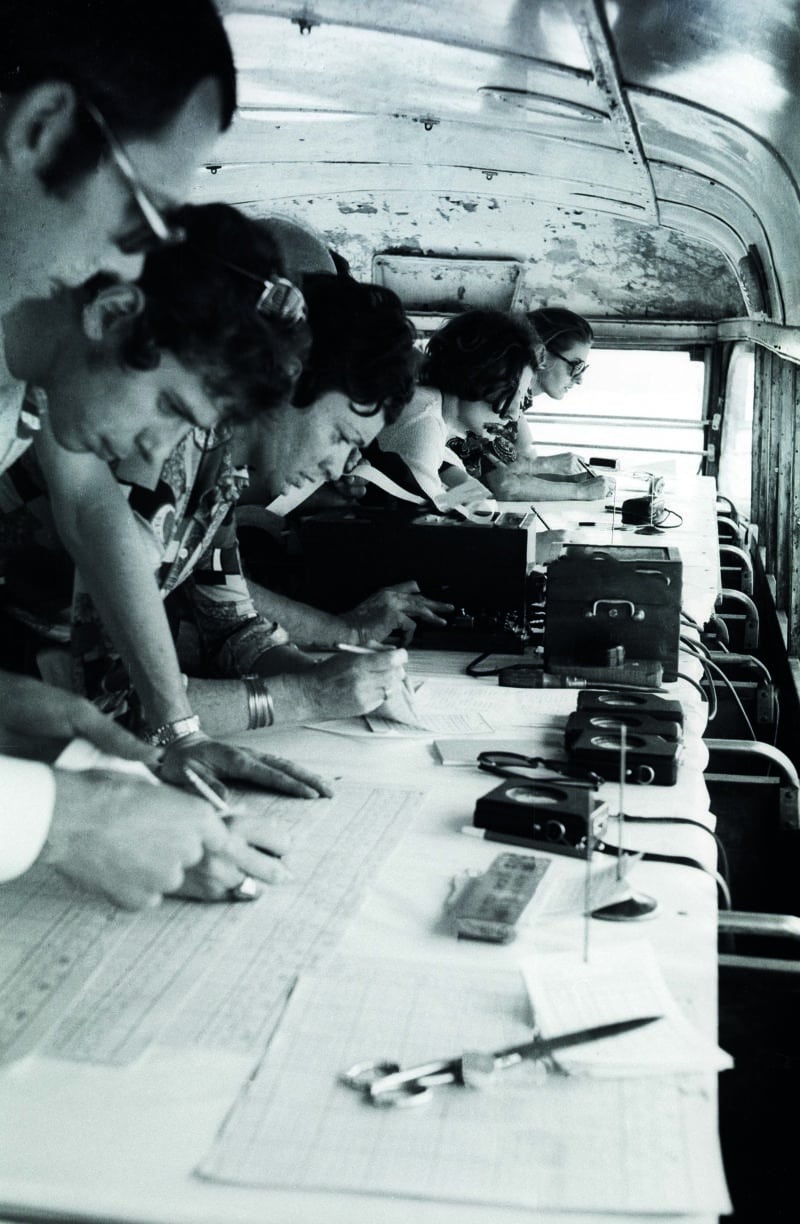

Timekeepers and officials were squeezed onto the top deck of a double-decker bus…

Jutta Fausel-Ward

…which provided an elevated view over the featureless track

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Brian Cullen in his BT23C with mechanic Evan Hughes. The three policemen seem unbothered by the crowd pushing to the track edge

Jutta Fausel-Ward

While that furore was contained, the Formula Vee grid prepared for an event they needed to contest on the knife-edge of controlled speed so as not to leave the circuit, which would guarantee contact with local geography – and/or spectators.

The race started at midday. While scheduled for 20 laps, it was red-flagged after 15. Safety precautions were non-existent. There were bales of barbed wire roadside, with spectators standing on the edge of the road surface inside and outside the track.

“I’ll never forget it,” says Bell. “When the cars began to split into groups, people were crossing the track in between!”

Formula Vees assemble for their curtailed race. “You couldn’t tell the track from the pit lane or the car park,” says Derek Bell

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Race director Gerd Kroeber’s nerves were somewhat frazzled. At that point, Bertil Roos’s RPB led from Helmuth Koinigg, Kaimann, and Helmut Bross in a Fuchs. The stewards assessed the potential risks of a crowd they couldn’t control with more powerful F2 cars circulating, and potentially leaving the track.

“All the drivers got together to say it was too dangerous to race,” says Cullen. “The organisers said we had to or there would be a riot. We came to a compromise: we would pretend to start the race but the mechanics would have the transporters ready. We’d do one lap and drive straight into the paddock and load up and go before the crowd realised what had happened. The organisers divided the prize money equally among the drivers.”

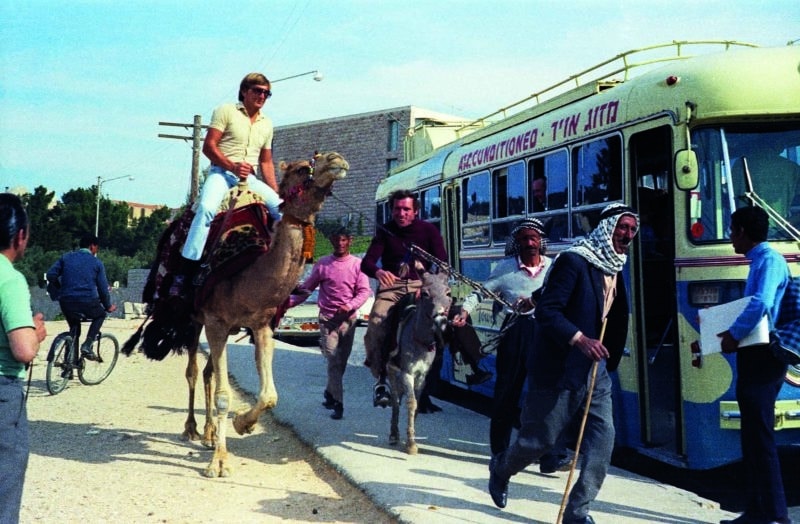

“We were on the grid warming up and that lunatic Brambilla just set off, weaving from side to side, one lap and into the paddock,” says Bell. “He’d done a good job of clearing the track so I floored it and did the same.” After that the meeting was ended, with the German organisers just happy that nobody had been hurt.

Unequal mounts: Bell’s camel surely has the legs on Vittorio Brambilla’s more agile donkey

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Derek Bell atop his dismantled Brabham

Jutta Fausel-Ward

Future F1 driver Patrick Depailler ran a works Tecno 70

Jutta Fausel-Ward

The teams departed: cars, equipment, drivers and organisers boarded the MS Nili from Haifa back to Genoa, and that was the end of international motor racing in Israel until construction of the F3-standard Hatzerim Motor City circuit in 2018.

While the locals were keen to run the event again, no-one was brave enough to try. The promoters and organisers had wonderful intentions to bring motor racing to a new market; the elements of goodwill and commercial intent were laudable. The race organisation was well covered by the Wiesbaden Auto Club crew, but they were handed a poisoned chalice that was unusual in its level of incompetence and political and religious naivete.

What an interesting obscurity, though – a race meeting in the most unlikely of places, which proved almost as incendiary as so many things in the Middle East.