John Gentry: The changing man

In motor racing, John Gentry has left few stones unturned. Damien Smith meets the popular British draughtsman and engineer to look back at an extraordinary Zelig-like career that has taken in Formula 1, Can-Am and 500cc motorbikes. Not bad for a man without design qualifications

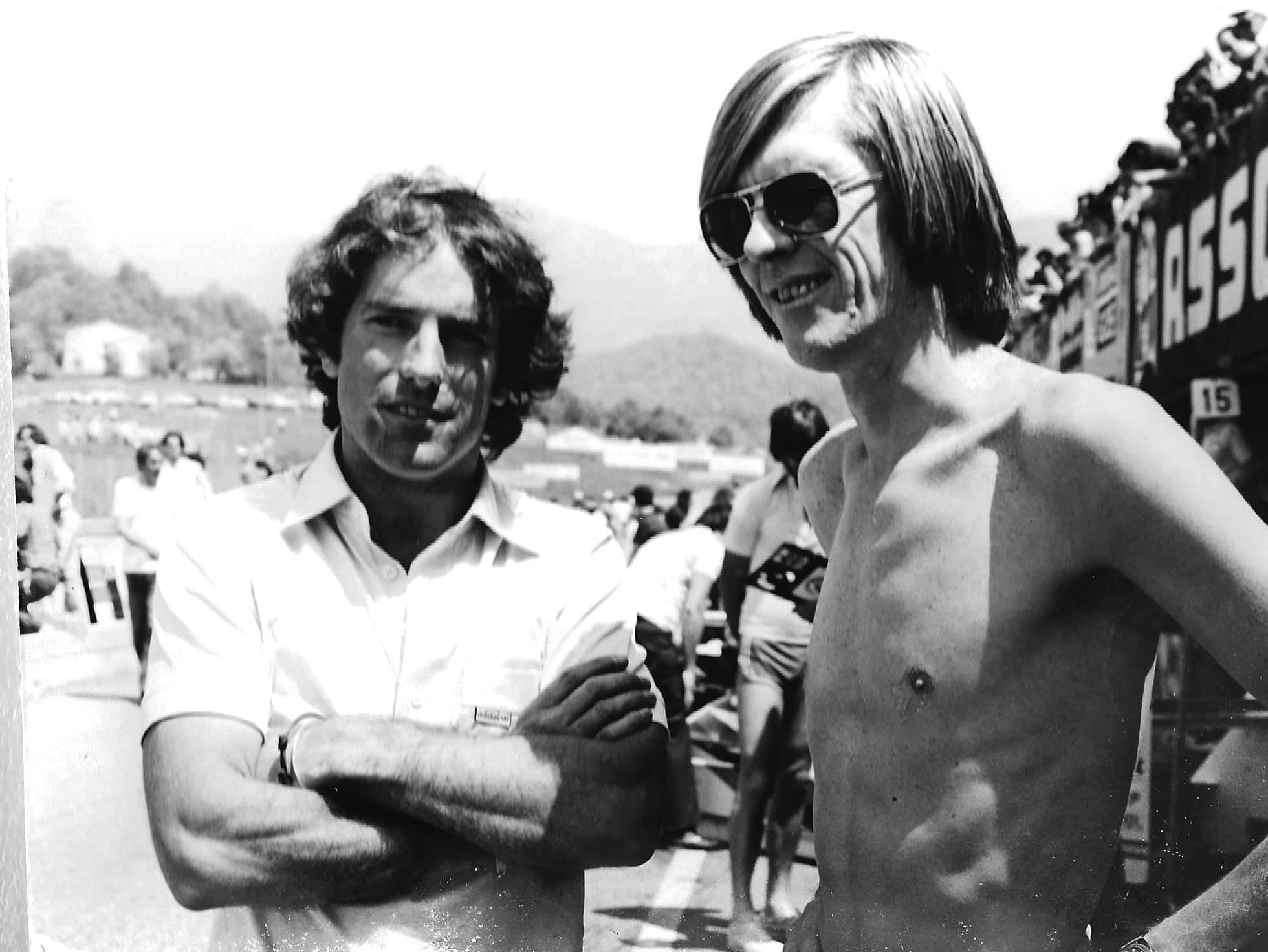

With Thierry Boutsen at Benetton in 1988

March, Shadow, Fittipaldi, Tyrrell, ATS, Toleman, Renault, Alfa Romeo, Brabham, Benetton; then there was a leftfield switch to Suzuki and Yamaha in motorcycling, before a return to four wheels to work on a Volvo estate touring car… Prolific John Gentry has been a rolling stone during his multicoloured five-decade motor sport career, spent as a master draughtsman and race engineer for the likes of Emerson Fittipaldi, Chris Amon, Gilles Villeneuve, Jean-Pierre Jarier, Teo Fabi, Derek Warwick, Elio de Angelis, Ron Haslam and many more. This is some racing life, and for a man who prides himself on his dedication to the minutiae of detailed design, it all seemed to happen purely by chance.

He welcomes Motor Sport (pre-lockdown) to his beautiful home nestled in a corner of a picturesque Oxfordshire village. The craggy features, creased smile and soft timbre as he speaks reflect a surprisingly gentle character for a battle-hardened, well-travelled racing lifer. John is a popular man in the business and it’s easy to see why.

Talking shop with fellow designer Ricardo Divilain, 1979, the Brazilian who was technical director at Fittipaldi until 1982

Before we get down to the details of his incredible life, there’s a tour to undertake. Up a steep flight of stairs is his converted attic office, a perfect nook with plenty of natural light, lined by photos – motorcycles outnumber the cars – and souvenirs that each carry a story. In one corner, he points to what could be a work surface, if it was clear. Somewhere under there is the draughtman’s board he took with him when he left March – for the first time.

Back downstairs, we step into his wife’s stylish, more spacious and less cluttered office (well, she is an interior designer) and John draws back a curtain. What it reveals is his ‘museum’: a cluster of classic motorcycles pristinely restored by his own hand and packed into a secret room. There’s a Suzuki RG500 in factory Sheene colours, a BSA Goldstar, a 350cc Yamaha and myriad Hondas, his favourite machine maker. Hung from a rail is his collection of instantly recognisable leathers: the names read Schwantz, Haslam, Kocinski… He’s enjoying our astonishment as we gawp open-mouthed in wonder. Motor sport has clearly treated him well. So tell us your story, John…

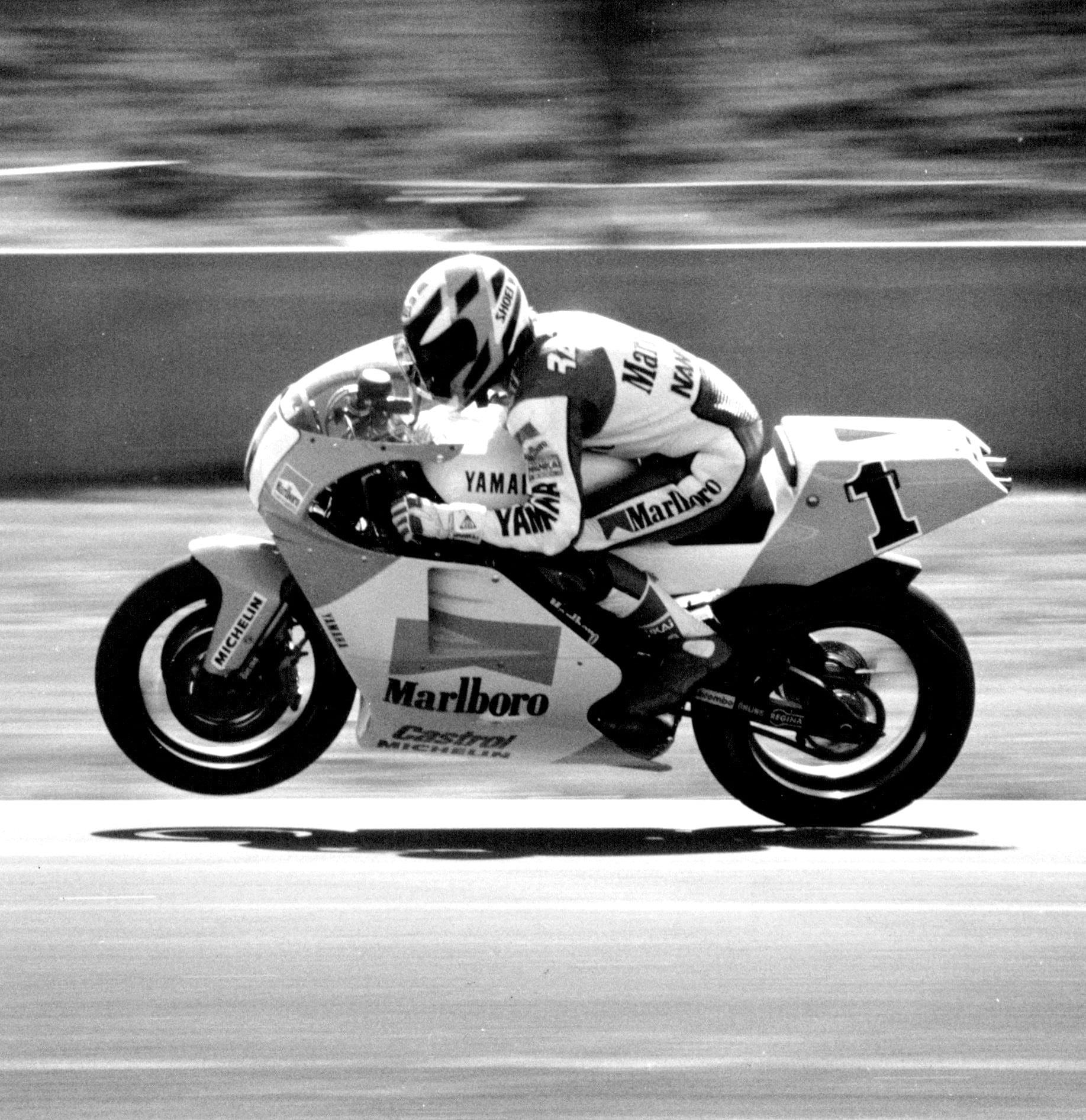

Gentry worked for Roberts Yamaha in the Wayne Rainey era of the early ’90s

Craig Golding/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

Gentry was born in Kingston upon Thames in 1950 and left school at 15 without a single qualification. “I didn’t enjoy school much,” he says. “I was good at technical drawing and football. I played for Kingstonian’s ‘A’ team, but wasn’t good enough to turn pro.”

The school youth employment officer, fearing for his chances of landing a job, suggested he become a TV repair man. “I didn’t want to do that: I wasn’t even old enough to drive so I couldn’t be the man in the van,” he says with a chuckle. “I persevered and saw an ad in our local paper, the Surrey Comet, for a junior draughtsman in a contract drawing office in Chessington. I went for the interview and got the job. It was a really good grounding.”

“I owe Robin Herd and Geoff Ferris everything. I got the job”

Today, budding engineers with high ambition need a raft of top-grade qualifications even to be considered by premier-ranking companies. It was a different world in the 1960s. “I saw another job advertised in the Comet, God bless ’em, for a draughtsman at AC Cars in Thames Ditton,” says John. “AC were known for the Cobra, of course, and the 428, so that was good. But I found myself getting involved in a project for the Ministry of Health: invalid carriages, the little blue three-wheelers. AC had the contract to build those. It had a Steyr-Puch engine in the back, which was easy enough, but you had to design the steering mechanism for all kinds of disabilities, which made you work a bit. I enjoyed that, but at the same time I was getting more interested in motor racing.”

Out of nowhere, Gentry was about to embark on an odyssey unmatched in racing.

First contact: March

He spotted another ad, this time in Autosport, for a draughtsman job at those Johnny-comelatelies at March. “I went up to Bicester and was interviewed by Robin Herd and Geoff Ferris. I owe them everything. That was it, I got the job. It was 1970, I was still a teenager.”

Luck doesn’t cover it. “After six months or so Geoff moved on to Penske and I was the only person in the drawing office, which was about as big as my kitchen,” says John. “For the guys building the F1 cars, the basis of it was drawn, but odds and sods, brackets and so on, they would make them themselves from their own sketch. Then they’d give it to me to make a proper drawing so they could make some more.

2. March co-founder Robin Herd, right, gave John his first big break

“I was very lucky, all the way through. It was in a period where no one had a calculator or computer, it was just what came out of your head and put down on a bit of paper. And I was lucky to meet people like Robin, who was a fantastic guy, the kind you wanted to work for. Although there weren’t many instructions.”

Next stop: Shadow and Fittipaldi

After a few years, Gentry had itchy feet – what would become a running theme. “I was not going racing at March and I wanted to know about the complete car,” he explains. “I wrote to Tony Southgate, who was at BRM, because they made their own chassis, gearbox, engine – everything. He wrote back, saying, ‘Forget BRM! They are not much longer for this world. But don’t despair, we are going to start a new F1 team and maybe there’s a place for you there.’ I went to see him at Bourne and he was already working on the DN1.

“Shadow was a good place to work. In the drawing office there was me and Andy Smallman. He was a very good draughtsman. Between us we produced all the detail drawings for the F1 and Can-Am car in the same year. Tony’s drawings are fantastic and beautiful, quarter-scale of the whole car and full scale of the areas that he was trying to dictate. The rest of it was up to us. Tony would show us where he wanted a radiator, but we’d have to devise a fixation for it and make sure it didn’t rattle itself to death.”

“Chris Amon hadn’t got paid, so he spirited a Formula 5000 Talon car away. God knows how”

Smallman moved on to Graham Hill’s eponymous team, only to be among the victims of the plane crash that also claimed the boss and driver Tony Brise in November 1975. “That job could have been for either of us,” says John.

Another opportunity beckoned in 1976 when he was lured by the promise of working with a double world champion. “I’d got to know Jo Ramírez, who was involved in Fittipaldi. They had a tiny workshop in Reading. It was when Emerson was about to leave McLaren and join a team with no history [Copersucar]. We built the FD04, which wasn’t a great car. We went testing just before Monaco and they took me, so I was starting to get into engineering.”

Fittipaldi qualified seventh in the Principality and in the race scored one of three sixth places for the season. “After qualifying, his face was purple,” says Gentry. “‘Well done,’ I said. ‘Yes John, but I shouldn’t have to drive like that.’ Emerson was very good for me. He’d sit and talk about the car, what he wanted and how we could do it. I was only there for a year.”

Chaos with Amon and Villeneuve

Next followed an adventure Gentry drolly describes as an “eye-opener”. Through Jo Ramírez, John found himself drawing a Can-Am car for another racing hero: Chris Amon.

“It was a Formula 5000 Talon that Chris had driven down in New Zealand in the winter, but hadn’t got paid, so he spirited the car away,” says John. “God knows how, I didn’t ask! The design job was to create a single-seater Can-Am car, and we did it at a funny little workshop owned by this bloke called Dallara in Italy. There were three of us: Barry Sullivan, Kerry Adams – good mechanics from McLaren – and me. Giampaolo Dallara founded a company to make the bodywork and got involved in its design. The rest was down to us.”

Not for the first time during our conversation, Gentry shrugs: “The car was not great, I have to say. Chris was going through a bad period in his life, trying to divorce his wife while his girlfriend was pregnant. Vairano, near where Dallara is based, was a very short circuit then and we took this bloody great car on a go-kart track. Chris couldn’t tell if it was good, bad or indifferent. So we put it in a box and off we went to the first race at St Jovite in Canada.”

During practice, Amon was shaken when Brian Redman’s Lola took off at 160mph in an accident that almost cost the Lancastrian his life. “Chris was very upset,” says John. “He thought he was doing this because it was supposedly a bit safer. We qualified second and we were running second in the race when Chris brought it in. He said, ‘I’m going to stop’. I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ He said, ‘I’m not going to drive another racing car – ever.’ That was it.”

4. Helping Gilles Villeneuve get comfortable in the Wolf-Dallara Can-Am at St Jovite in 1977 following Chris Amon’s departure from the team after only one race

Amon briefly abandoned his three amigos, who were left high and dry with no means to leave their hotel, never mind travel to the next race. The car might have been known as the Wolf-Dallara, but Gentry saw little sign of patronage from Canadian oil billionaire and F1 entrant Walter Wolf. Then Chris returned, saying he’d found them a driver.

“It was a young local kid who was doing quite well in Formula Atlantic,” says John. “Gilles Villeneuve came down to St Jovite in a motorhome with his missus and child – Jacques – to take a look at the car. He walked around it wearing this funny little hat, sat in it and said, ‘Yeah, I’ll drive this.’ So we had a driver and we could go on to Watkins Glen.” A gearbox problem frustrated Villeneuve, but at Elkhart Lake he finished third ahead of Redman’s replacement and eventual champion Patrick Tambay. “Then we ran out of money.”

Tyrrell’s fan car

Gentry returned to the UK newly unemployed, but not for long. “I got a phone call from Maurice Phillippe. He had moved to Tyrrell, was in the throes of designing the 008 and needed help on the detail stuff. Derek Gardner was still there at first. They were still running the six-wheeled car, and he didn’t allow us into the drawing office! There was a double garage down the bottom of the woodyard, and Maurice and I had our drawing boards in there. When Derek left we joined the main office – although there was only one other guy in there. I really enjoyed working with Maurice. He didn’t have to, but we’d sit there until 10pm with him explaining why he did something on a Lotus that he’d designed. He was that kind of guy. He wanted to help you understand.”

The 008’s finest moment was victory at Monaco in Patrick Depailler’s hands. But in the same year Gordon Murray’s Brabham BT46B fan car threatened to fundamentally change the F1 game, Gentry recalls how Phillippe almost got there first. The 008 was originally designed as a fan car, too – only Tyrrell couldn’t make it work. “Maurice wanted to hide the radiators, so he put one lying flat underneath the car where the fuel tank would be, and there was a fan driven off the crankshaft to suck the air through,” explains John. “We went through a lot of designs of the fan, which was restricted for size, and we had to make the fan vanes ourselves. The guy in the workshop on a milling machine was incredible. We went testing, but it just got too hot. So in the end the radiators sat on top of the bodywork, as an afterthought.”

The 1979 Formula 2 European Championship in 1979 with Hans- Joachim Stuck, left, and Marc Surer at Hockenheim in the March 792s of Polifac BMW Junior Team. Gentry can be seen making notes. Surer pipped Brian Henton to the driver’s title

In 1980 at Toleman it was difficult for us because we were up against Brian Henton and Rory Byrne, who were the best in the F2 business and were up to all sorts of tricks which we had to counter. We found a few things we kept for ourselves, which is what it was like back then…

John understood my frustrations when we went to F1 and were five seconds off the back of the grid. He appreciated that I still gave it 120%. We grew together as driver and engineer, which is why I took him to Renault. We never fell out or lost that trust. He also had an unbelievable bond with the mechanics, and if he wanted to change the engine at midnight they’d do it. Even at Brabham after Elio’s death, we knew Riccardo Patrese was the main focus of the team and we worked around that.

He’s even godfather to my eldest daughter. We were together for so long. He’s a sensitive, unassuming guy too.”

Didier Pironi finished fifth in the 1978 Monaco GP driving the Tyrrell-Ford 008, but team-mate Patrick Depailler won the race. It was the car’s greatest moment

Gentry has another memory from his time at Tyrrell. If only he had a photo… “At Christmas time Tyrrell always had a big do,” he says. “They had a guy come along as Father Christmas to give presents to the wives. Who do you think it was..? Bernie Ecclestone!”

March again — after its diversion

Old friend Robin Herd corralled Gentry into Günther Schmid’s ATS F1 operation having sold March’s F1 assets to the famously volatile alloy wheel magnate – then quickly baled, leaving John to engineer both Jean-Pierre Jarier and Jochen Mass at Kyalami. “Schmid had a reputation, although he was always OK with me,” says John. He then adds: “When I left, Günther sent the police to my house saying I’d stolen all the drawings for the new car.”

It was Herd who steered Gentry towards Formula 1 team ATS. Here, he is in discussion with Jochen Mass at the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder in 1978

In the ATS team kit in 1978; team owner Günther Schmid would later report John to the police for alleged theft of original drawings

Out-of-character guilt pangs led Herd to offer Gentry a role back at March. “Robin said, ‘I got you into this – come and engineer some F2 cars.’ So I did that, with Teo Fabi. We had a good feeling together,” he says of a 1979 season in which March ran a stable of works cars and Marc Surer claimed the European title. “Each engineer had two cars, and I had a rental for each race driven by Stefan Johansson, Hans Stuck and others. That was interesting, to see how each one went about it.”

Gentry enjoyed working with Teo Fabi in Formula 2 at March in 1979. Fabi’s best result was second at Zandvoort

Gentry combined his F2 engineering duties with designing a striking new Group 5 BMW M1 that had been commissioned out to March. “BMW was supposed to supply a really powerful 600bhp engine and it was completely new, from monocoque to suspension,” he says. “Robin started a new company for that car working out of Cowley, with about a dozen people building it. But the engine didn’t arrive – I’m not sure it ever existed – so we only had a Group 4 engine. It faded away. We did go to Le Mans with it and spent all day under the first umbrella for scrutineering in the square.

‘What class is it in?’ ‘It’s a Group 4.’ ‘No it’s not.’ Robin came out and doctored some paperwork from his road car… Anyway, we got through, but we were in the Group 6 class and we didn’t qualify. A strange time.”

Toleman, Derek Warwick and Johnny Cecotto

Gentry’s five years at Toleman represents his longest spell in one race team, and he joined at the end of 1979 just as Rory Byrne was working on the TG280 that would dominate the 1980 European F2 Championship with Brian Henton and Derek Warwick. “I knew Roger Silman, who was running the cars, and he said they were going to build their own car,” says John. “At first we were in Tom Walkinshaw Racing’s small drawing office, just Rory, me and two drawing boards. Rory did the bodywork and I did the rest of it.”

It would prove a pivotal campaign. Byrne engineered Henton, with Gentry teaming up with Warwick, creating an edgy intra-team rivalry that mostly remained good natured – with the odd exception. “Henton whacked me once,” says John. “We were in Enna and that weekend Brian was on course to win the championship. One evening as we were going out to dinner, he dropped back from the guys in front and punched me! I said, ‘What was that all about?’ ‘For making this year so difficult.’

The (slightly unhinged) band-of-brothers spirit carried Toleman through four remarkable F1 seasons in which the team rose from rank no-hopers to genuine contenders with a rookie Ayrton Senna in 1984. Gentry formed a close bond with Warwick, and then when Derek left for Renault in ’84, he naturally gelled with incoming ex-motorcycling world champion Johnny Cecotto. “We got on like a house on fire,” says John. “Then he had that practice accident at Brands Hatch.”

The Venezuelan broke both ankles and his right kneecap, which abruptly ended his F1 career. In a team increasingly revolving around Senna, Gentry felt the team showed a lack of consideration in difficult circumstances: “It was me that had to go and fetch his clothes from the hotel and phone his girlfriend,” he says. “It wasn’t very nice. I’m sure it wasn’t intentional. It was probably me making too much of it. I went to the hospital with him and they were saying they were going to amputate his foot. I said, ‘You can’t do that, you need to find another way – the guy’s a professional racing driver.’ His father and his girlfriend got him back to Munich.” Cecotto recovered to enjoy success in touring cars and endurance racing, but the experience left its mark. “I’m a bit sensitive sometimes and that situation touched me,” he says. “I didn’t want to be at Toleman any more.”

“They were talking about amputating his foot. I said ‘you can’t do that’”

Warwick comes calling

Gentry briefly pitched up at Alfa Romeo’s Euroracing-run team, but his only happy memory is of the Alsatian that would sit in his office all day. When the team failed to pay him, he headed home for Christmas and didn’t go back. But a call from Warwick led to what he thought was an unlikely move to Renault.

“I didn’t think they’d want me, a factory team like that,” he says. “But Derek said, ‘You’d be surprised.’ I was definitely only a race engineer there. They had a big design office which they weren’t keen for me to be in. I asked for a drawing board and the management said yes, but the guys in the design office didn’t want that to happen. There was a bit of animosity. They had this Renault-manufactured gearbox and it was massive, so heavy. I asked, ‘Why is it like this?’ I said to Derek, ‘One day I’d like to go down to the stores and knock off a few grams from each component.’” But the discontentment didn’t last – Renault pulled the plug on the team at the end of ’85. “Just my luck!”

Tragedy at Brabham

Before the 1985 season was done, Bernie Ecclestone had recruited Gentry for Brabham. But with Nelson Piquet on his way to Williams for ’86 he joined just as the team had begun its slow decline – accelerated in part by Gordon Murray’s low-slung BT55. “Gordon was in a strange time in his life,” says John. “A very nice guy, a really good draughtsman, beautiful drawings – funny, that’s how I look at people: can he draw! But the BT55 was a disaster. It was way too long in the wheelbase.”

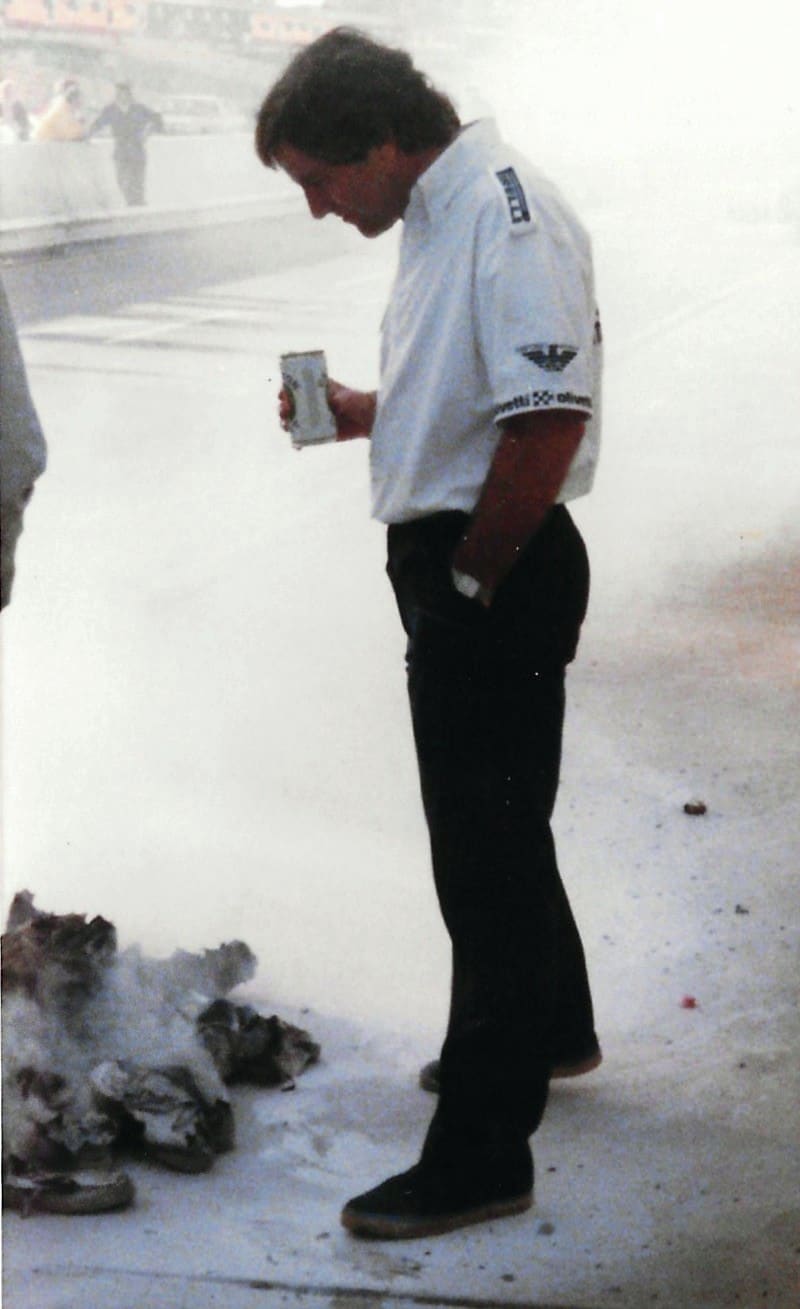

Unpopular Brabham team shoes meet their end after the last F1 race in 1986

Gentry was assigned to engineer Elio de Angelis, another of the great driver partnerships of his career. But his hushed tone drops another notch now. John was there at the Paul Ricard test when the popular Italian crashed to his death, succumbing to smoke inhalation after being left trapped in the car during a session in which safety crew support was sorely lacking. It’s clearly a tough one for John to talk about. “It was the first time I’d been involved in a fatality on my car,” he says. “I almost didn’t want to do it any more. Elio would say to me, ‘Why are we testing, John? We’re all here, we’ll all learn a little bit, go away and the next race the grid will be exactly the same.’ He was a gentleman, that guy. He could play the piano to concert level, even though he had a bit of a finger missing from choking the carburettor on his kart. Touched me quite a bit.”

Warwick stepped in for de Angelis. “There was a brand new car for him and we took it up to Donington,” says John. “He crashed it in the Craner Curves and damaged the monocoque. Bernie came up to me and said, ‘You’ve always gone on about the length of the car. What have you got to do to make it work?’ ‘Make it shorter, but it’s impossible.’ He said, ‘Take that monocoque that your mate crashed and do what you need to make it work.’ We literally chopped eight inches off the back.”

Left-turn to Suzuki

Depressed by the loss of de Angelis, Gentry moved to Benetton. A chance encounter with a chap wearing Suzuki team gear at an airport led to a welcome diversion and one that revived his motivation. “We got chatting and he invited me to go down to the workshop, the old John Surtees place in Edenbridge.” The contact led to a job offer as race engineer to Kevin Schwantz and team-mate Ron Haslam in the premier 500cc grand prix class. Quite a transition.

“I think they imagined that if you’ve been in F1 you must be incredibly intelligent,” he says with a smile. “F1 was at the top and motorcycle racing was considered lower, so could I bring some F1 ideas? I did a little bit. Silly things like debriefing. Before I went there the rider would stop, take his helmet off, sit on the bench and say what he thought to his mechanics. And that would be it. I’d go to Schwantz’s motorhome, which was looked after by his parents, and his father used to listen in. In the end Kevin’s father said to him, ‘Give the guy a chance.’ Until then I was close to thinking, ‘It’s not for me.’”

Team talk with Thierry Boutsen while at Benetton in 1988

Gentry says it took three months for him to be accepted, but he quickly built a rapport with Haslam. “He was dyslexic, didn’t read or write,” says John. “But at that time a lot of riders were buying radio-controlled helicopters, bringing them back to their motorhome, then realising they couldn’t put them together. They’d take it to Ron, who would build it. He would talk for a long time about stuff like gear ratios, whereas the others were not so fussy.

“If I was going to do something full-time now and I could, I’d do bike racing again. Once I was accepted, I probably did prefer it. But it wasn’t so intense. I wasn’t designing anything, although I did when carbon brakes came along. They’re sitting there, either side of the front wheel getting breeze on them, they’re cold and don’t work. So I sketched out a couple of ducts to keep the air off them. We went testing with Ron and he said, ‘These are much better.’ The Japanese guys came along and said, ‘What’s that?’ I explained. ‘We can’t use that. You can’t design anything for a Suzuki bike because it has to come from Suzuki.’ That’s how it was. The ducts did appear again, if slightly different.”

Working for ‘King Kenny’

Gentry describes the two-wheeled world as “a gypsy life” and after two seasons returned briefly to familiar territory with Leyton House. “That’s when Kenny phoned up and said, ‘Come back to bikes and work for me.’” Saying no to ‘King Kenny’ Roberts, the three-time world champion and boss of the Marlboro Yamaha factory team? Not likely.

John worked for Roberts for three seasons, in the heart of the Wayne Rainey era from 1992 to ’94, as engineer to the Californian’s teammate John Kocinski. The Arkansas rider is remembered for his personal eccentricities, but those quirks never caused a problem for his new engineer from ‘eff wun’. “When I took the job people said, ‘You’re mad, he’s crazy,’” says John. “For me he was just a good rider. I didn’t know any better. We got on. His cleaning obsession, his OCD, I accepted that from him. In the garage, for example, he’d come in and you could see he was looking for somewhere clean to put down his helmet. All I did was tape some blue-towel to the bench and said, ‘Guys, leave that alone. I don’t want to see anything else there. It’s for John’s helmet.’ Later, he said, ‘Dude,’ – they all called me Dude – ‘did you do that?’ We understood each other. Little things like that encouraged him to work with me. At his last race, I said to him, ‘We can win this.’ He said, ‘If I do, I’ll s**t on the floor.’ He won and we drew a big loo seat for him!” Fortunately, Kocinski didn’t follow through…

“If I was going back to full-time now, I’d do bike racing again”

Gentry also has happy memories of how the boss let off steam at the end of a season. “Kenny would invite a bunch of us to his ranch for some R&R for three weeks,” he says. “He’s got a lovely place: Tarmac oval, dirt oval, motocross track – big place. There’s motorbikes on the floor, and they’re all little, 125s and 80s. He’d say, ‘If you see a bike on the floor and you want to ride it, you’ll probably have to fix it.’ He took me one time to this dirt track with an 80cc Yamaha and told me to slide the back wheel because ‘that’s what your rider feels on a 500cc on Tarmac’. He taught me an awful lot, an amazing guy. I looked up to him – still do.”

Volvo estates and toy dogs

From ‘King Kenny’ to Tom Walkinshaw – quite a contrast. In 1994, Gentry found himself working on TWR’s Volvo British Touring Car: an 850 estate. John didn’t bat an eye – “I didn’t think that much about it, I was just drawing” – although he remembers the kerfuffle when they bought a barking toy dog from Hamleys and sat it beside Jan Lammers and Rickard Rydell. “Aerodynamically, the car was better than most because with the box back there was less lift,” he says. “That’s all it had going for it.”

Warwick came calling again in 1996 when Gentry joined him in the formation of Triple Eight, which had won the contract to represent Vauxhall’s BTCC interests. He quit that job more than 20 years ago, but this rolling stone didn’t stop. There was a five-year spell at Activa Technology working for Yamaha and Dome; race engineering GP2 drivers such as Neel Jani and Adam Carroll; spells in A1GP; and two World Endurance Championship seasons with top LMP1 privateer Rebellion. Today, he’s still rolling, heading to Italy to advise a young driver.

What makes him most happy these days is fettling his pristine collection of motorcycles. “Racing is something I do now to earn a few quid – although still to the best of my ability,” he says. “The lad I’m working with, just being there is worth a couple of tenths. There’s more time in him than the car, let’s put it like that.”

Still, it beats fixing tellies.