Resurrecting the Sharknose Ferrari 156

When Enzo Ferrari ordered the scrapping of all 156s, it assured mythical status. Replica owner Jason Wright tells the story of its return

The pair of Sharknoses built by Setford & Company

After the disappointing 1962 season, Commendatore Ferrari himself ordered the cars to be cut up and the pieces to be used in the concrete of the factory forecourt. And so the legend of the ‘Sharknose’ began. The fact that none of the cars remained created a desire in the minds of many enthusiasts that survived unfulfilled until a car appeared in the late ’90s.

The musician Chris Rea had written a film script about Wolfgang von Trips and the Sharknose and had built a lookalike 156 as a prop. This car created a wave of new interest, leading to collector Jan Biekens commissioning Jim Stokes Workshop to build a car. Having found an original 65-degree 1500cc motor and gearbox, as well as chassis drawings, they built a replica that was accepted as the definitive 156 copy.

Biekens decided to sell the car and I jumped at the chance to buy it. I have been a lifelong fan of Phil Hill and so the purchase of the car became the realisation of a dream that I never imagined would be fulfilled. One of the conditions of the purchase was that the car be exhibited in the Ferrari Museum in Maranello for six months. When I purchased the car, I had planned to make some changes to the bodywork as I felt that it was not right, and I spent hours looking for photographs, but out of the blue, I found a set of original body drawings.

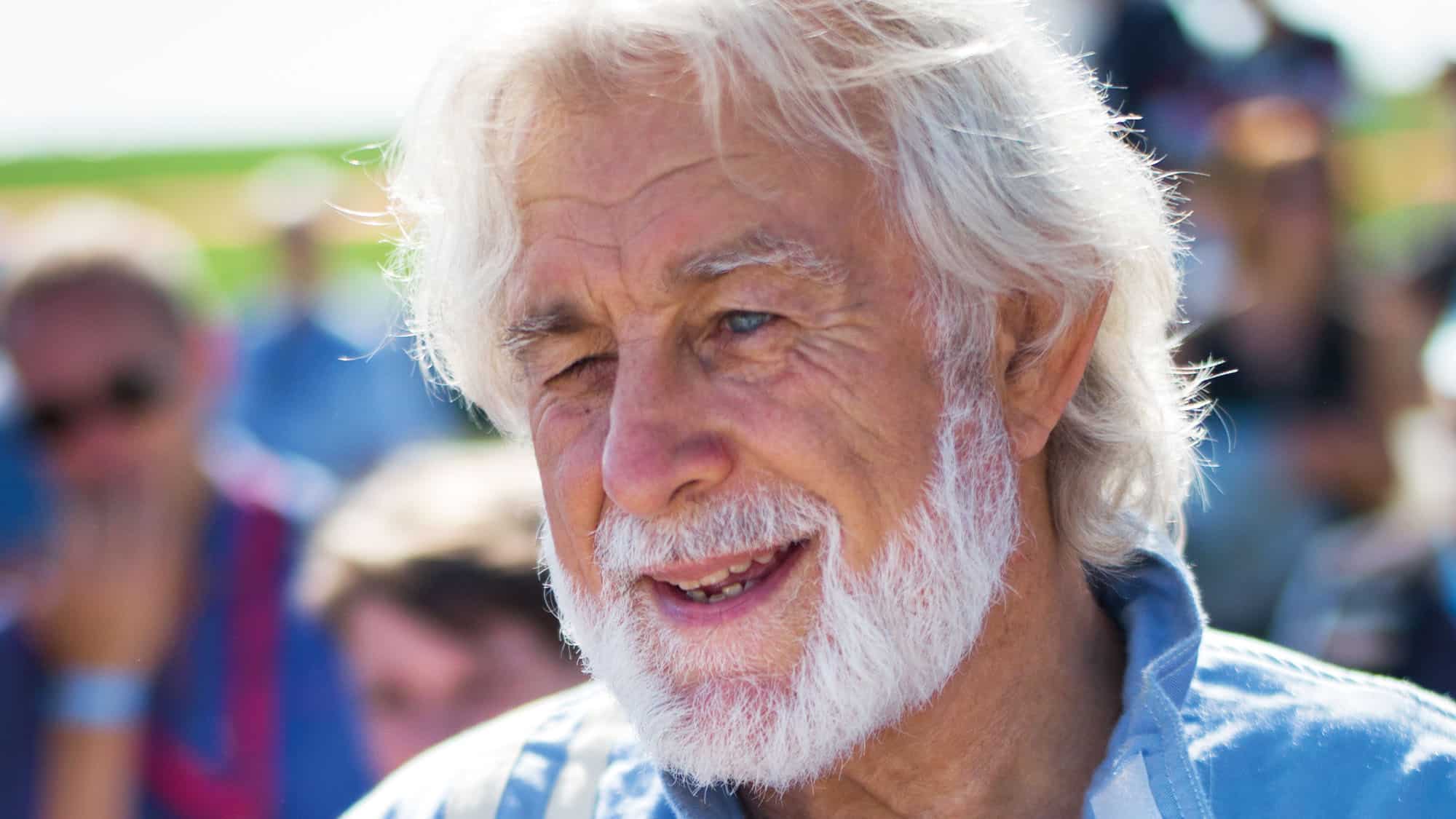

Owner Jason Wright

When the car was released from the museum, I delivered it to Setford & Company in the UK. Dan Setford and Mike Mark had built the car at Jim Stokes Workshop, and had since left, to start up on their own. It was decided to make a new body in the Italian style using hammers over a wire frame, as opposed to the English wheel which had been used on the Stokes car.

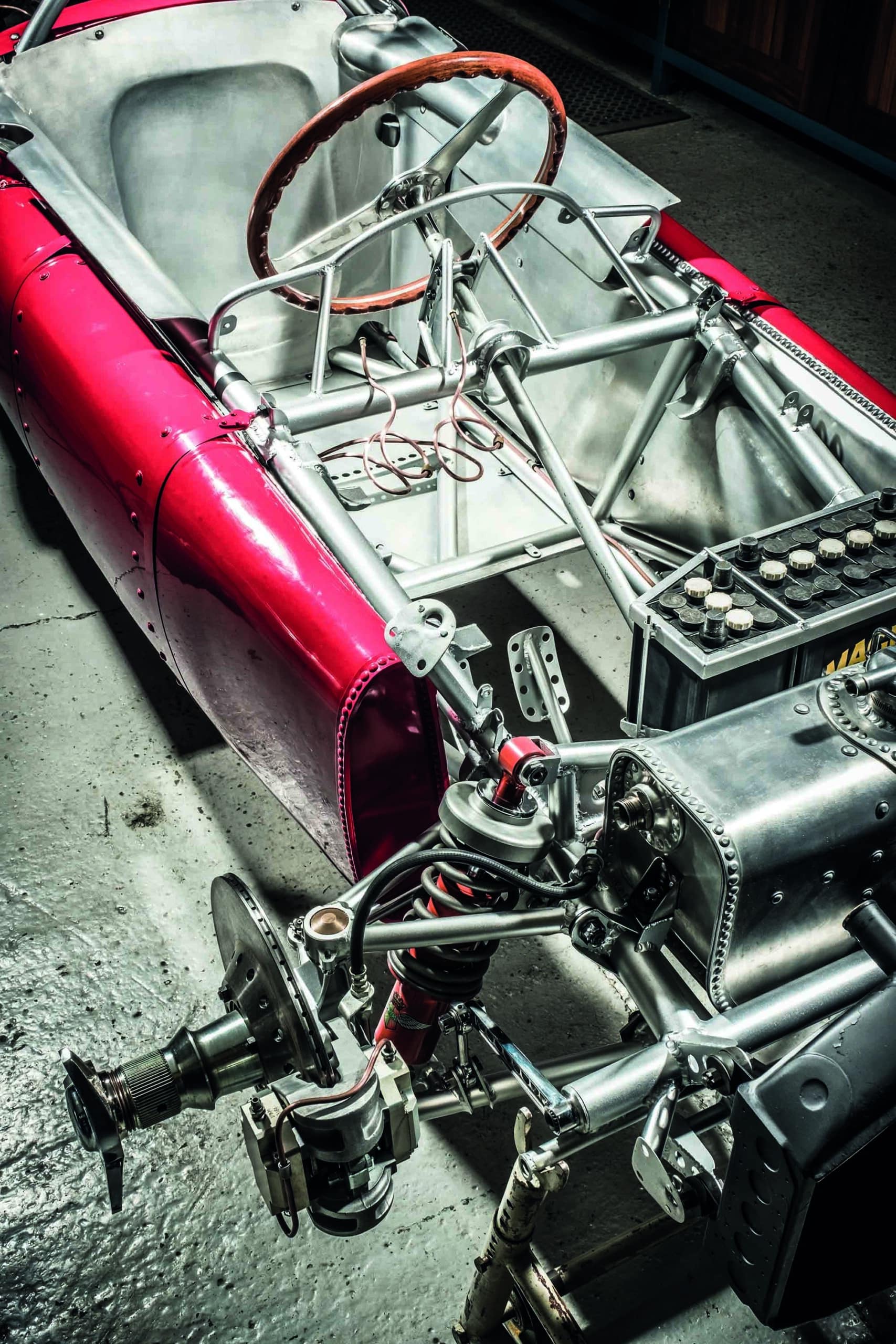

To do this Roach Manufacturing was commissioned. Roach, which built the Auto Union replicas for Audi, is among the finest coachbuilders in the world. Once this was decided, we started to look at the chassis, which had been TIG welded. While TIG welding is neat and tidy, the car looked more like a fine model than an old Ferrari. So it was decided to construct a new frame, new suspension and, in fact, a new car, using gas welding, copying the style of weld that characterised Ferraris of that period.

We salvaged instruments, wheels, brakes, radiator, springs, shocks, pedals, engine and gearbox, and everything else was reconstructed. Chassis, suspension, fuel and oil tanks were made using hundreds of proper Italian period rivets. Every nut and bolt was specially manufactured to Ferrari’s size and specification and original style European metric tubing was ordered. New Borranis (which has the original Ferrari drawings) arrived from Milan, and then, as so often happens when one is deeply involved in a project, a second engine and gearbox were offered to us.

The new car was meticulously based on period Ferrari drawings

This engine, a 120-degree V6, was numbered 002, which is the chassis number of the car Phil Hill drove to victory at Monza. At this point we decided to build a second car. Having an original gearbox was a crucial element, as they are complicated pieces of machinery and to replicate one would be financially prohibitive.

The second car would be a replica of the Phil Hill Monza car, and the 65-degree car would replicate the one that Ricardo Rodríguez drove in the same race. Building the 120-degree car has had its challenges. The engine was missing its carburettors and while they are triple-choke downdraft Webers with similar internal specifications as those of a Lamborghini Miura, they are very different externally.

Gear ratio detail

Fortunately the Schlumpf Museum has a 1963 Ferrari with the correct carburettors and while incorrect for its car were just what we needed to copy. The museum leant us its car, allowing us to copy the carbs and to study the welding, clips and fasteners, and all the bits that end up making a car look right.

That generosity stemmed from the fact that the introduction to the museum had come from Ferrari, and that we were not replicating something that existed. As Ferrari said, “You have the engines. They were only ever made for a grand prix car. It would be a shame not to see them run.” In fact, no one has heard a 120-degree Ferrari engine run since 1963.