Lost Sharknose Ferrari 156 rides again

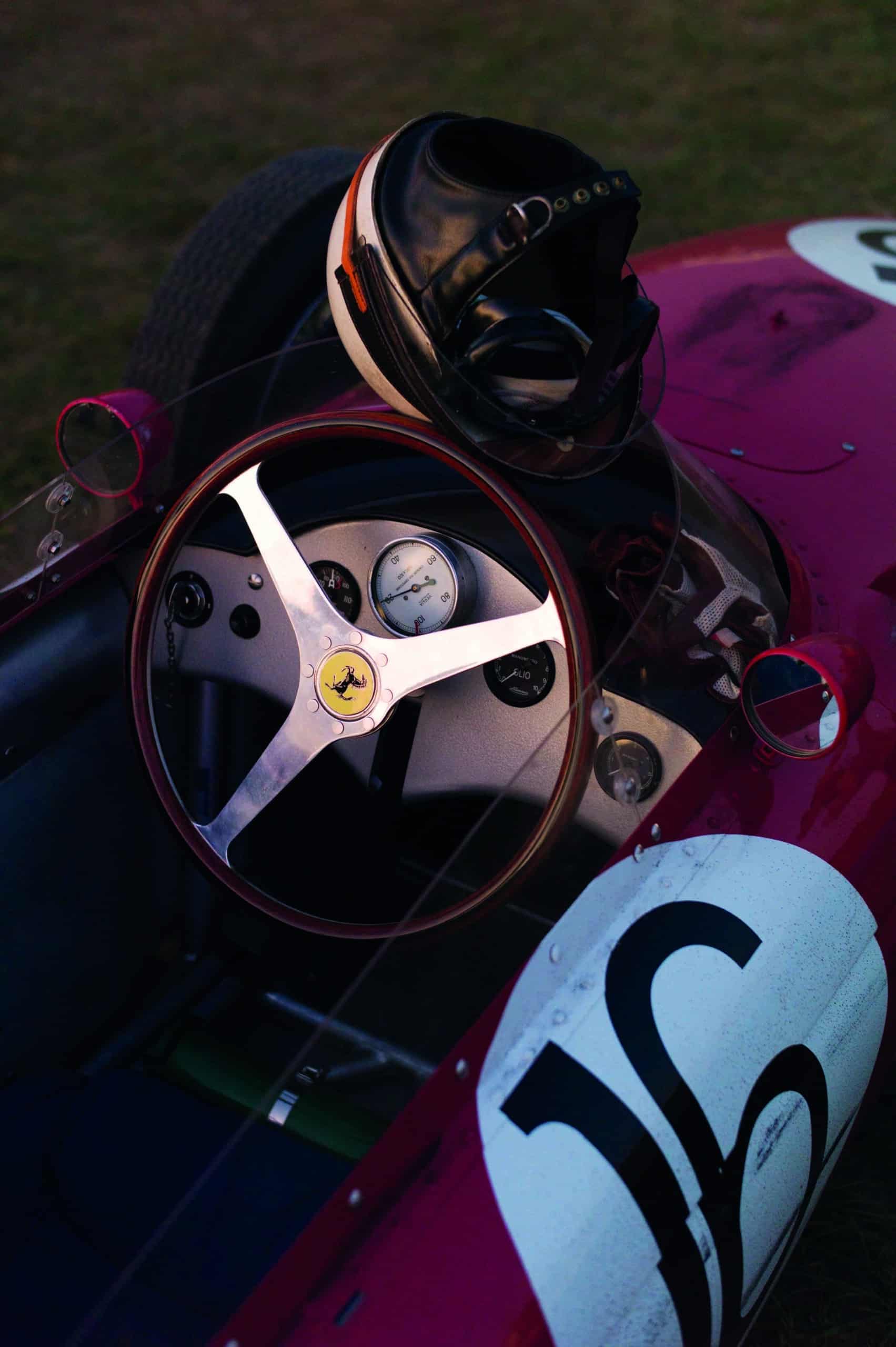

In 1961, Phil Hill was crowned F1 champion at Monza driving the Ferrari 156 –a race in which team-mate Wolfgang von Trips and 14 spectators were killed. Almost 60 years later, Phil’s son Derek Hill takes the wheel of a ‘Sharknose’ to experience what life was like for his father

It’s September 2019 and the Hill family is reunited with the 156 – this one a replica owned by the Europe-based American collector Jason Wright

Ernst Schlogelhofer

The Ferrari 156 ‘Sharknose’ interrupted the British Formula 1 revolution led by Lotus and Cooper-BRM in the first year of the 1.5-litre engine regulations in 1961 and gave Maranello a potent, if brief, performance edge that my father Phil Hill, Wolfgang von Trips, Richie Ginther, Giancarlo Baghetti and others took full advantage of in that season 60 years ago.

While the British teams gnashed their teeth over the regulation change, Ferrari made hay with Carlo Chiti’s V6 that had evolved out of Formula 2 since 1957. Its spaceframe chassis was conventional, but that striking twin-nostril nose, the neat mid-engine layout and Enzo Ferrari’s unfortunate insistence that all 156s should be broken up once they became obsolete has guaranteed the Sharknose a special place in the illustrious halls of Ferrari F1 history. That my father became America’s first F1 world champion in the car gives me a unique and personal connection to it.

In September 2019, I had a chance to drive Jason Wright’s wonderful replica at Reims and Zandvoort for a documentary I have been making about my father since 2009, a year after his death.

I’d driven one of Jason’s 156 replicas up the hill at Goodwood a couple of years before, but you don’t get a feel for a race car until you are on a proper circuit. Being able to drive it at Zandvoort was like going into a time capsule and having my mind blown. I always dreamt about what it was like to drive these cars, to be in a state-of-the-art grand prix car from those times. They are beautiful pieces of artwork, the sound and look of them, but you certainly feel vulnerable and exposed. It’s more like bobsledding than driving race cars as I know them. Then put it into the context of how long the circuits were and how fast, no chicanes or barriers to speak of… I always think of Spa, drifting through those high-speed sections with death right there on the edge, in a ditch or on an old stone wall, if you overstepped your mark. They were on a razor’s edge.

A few laps at Reims for a replica

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Phil Hill racing at the 1962 British GP, at Aintree; a poor season for Ferrari

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

It was an emotional experience to drive the 156 Sharknose. It forced me to get deeply in touch with not only who my father was but also the whole experience he had. It got me closer to understanding how difficult and challenging the environment was, dealing with the tragedies that were taking place – and their frequency, which we will never know again.

The documentary is a long ongoing story, motivated out of a desire to capture on film the people he worked with, while that window was still open. I have so many questions I wish I’d asked my dad, who was a larger-than-life figure. Racing brought us closer together, but that was such a short window of time – he got ill and there were difficult years. So the documentary has been all of that: piecing together who he was by understanding his experiences in the most poignant part of his life.

I’ve never had a date set for when this documentary should be finished. It remains a work in progress and I never want to say ‘this is when it will be done by’. Work on it goes in spurts: I get all-consumed, then I put it on the shelf, then it goes around again. So far it’s gone through three or four cycles. Every time I start to dive back into it I can’t believe what a rich story it is. My father was never really able to talk freely about his championship year of 1961 in a way that I think it deserves. It was fraught with so many complex emotions.

My father loved to tell funny and entertaining stories. Those were the ones he often repeated. But when it really came down to the detail of working with the team I never bothered to ask him technical questions: what was the structure of the team, who were you going to, Romolo Tavoni or Carlo Chiti about this or that, what were the politics within Ferrari? That was why I was so motivated to speak to these people who were there. I had great interviews with Tavoni and Mauro Forghieri, Carlo Benzi who was the accountant, and Franco Gozzi the PR manager, and just asked them as much as I could. Everyone really wanted to share because they knew my father and what he was all about. They were interviewed in Italian because I thought they would speak more freely (I had a translator with me and I know some Italian myself ). Then I got them translated and transcribed so I could read them like a book. It’s phenomenal when I read the interviews back.

I went on a binge with the camera in 2009 and ’10. Ferrari really valued my father’s relationship to them and I saw that first-hand by how much they welcomed me in, with a feeling more like family. It was amazing to walk around the factory grounds. I expected to have to travel through all of Italy for my interviews, but instead the story stayed right there in Maranello and its surroundings. Italians don’t move very far, I guess.

“Everyone really wanted to share because they knew my father”

My father was always consumed with hobbies, just to fill up the time when he lived and raced in Europe. Today the schedule of a sports person is so much more packed and they are able to get everywhere much quicker. Back then they were on a boat to Argentina from Europe, or flying down to Buenos Aires with something like 17 stops to get there.

Having had my own experience of living and racing in Europe helped me understand more about what that must have been like. It’s a lonely experience to be so far from home, but he had photography and his visits to antique shops… all his life he loved music reproducing machines, beautiful Swiss music boxes, self-playing musical reproducing machines. He played piano a little bit and the French horn when he was a boy, but he was more intrigued by things that could play themselves, that were mechanical.

He was obsessed with restoration of older things, which is what led him into his classic car business. In the past year, as a pandemic project I’ve been auctioning everything off. We sold the family home we were all raised in, plus more than 800 lots over three Gooding & Company auctions. Everything from memorabilia to car parts – it was so much, I need a little bit of a break. I’m a little burnt out by my father’s life right now.

Many original features give an authentic feel of Formula 1 racing in the early 1960s

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Looking back at 1961, it’s remarkable how few world championship races there were in that season – just eight and only the best five results counted. You had all this time and anticipation between them. One thing I’ve learnt is team politics played a bigger part than I imagined. We see team orders today, but there was no established dynamic of a team leader in that time period. It was left up to the drivers to jockey for position within the team and the confidence level could be extremely high, then extremely low from one race to the next. To me, he clearly was in a position where Ferrari could have benefited from establishing him more as the team leader. He was more established in the team, had just come off a win at the end of the prior season and was primed to take that role. But neither he nor Trips were ever granted that role. Ferrari left them to duke it out, all the while having team orders play a part in influencing their results. For a team that is in a position to make an honest run at the championship that can really augment the tension and have undesirable consequences. That’s probably what my father disliked the most, this chaotic, unstructured aspect within Ferrari. He had to fight tooth and nail for every win and result, on and off the track.

He and Trips were cordial to one another out of the car. But they were very competitive and selfishly after the same thing. Once they were on the race track, human nature took over and it played out much as it does today, even if it was an era where you had to play nice.

Running against the circuit’s flow of direction in front of the magnificent relic that is the main grandstand at Reims.

Ernst Schlogelhofer

The relationship with Richie Ginther was interesting. Richie was the younger brother of a friend in the neighbourhood where he grew up. They all grew up together in the post-war era with an interest in cars and hot-rodding. My father and Richie knew each other for years even before racing. Phil would drive Richie in his MGTC from Santa Monica to their jobs at International Motors in Hollywood, a foreign car import agency. To think where they’d be 12 years later, teammates as factory Grand Prix drivers at Ferrari.

When they got to Ferrari it was very clear what their positions were. For my father it was kind of like having your wingman with Richie, who probably had to stay in that place. He was never meant to be the more dominant player and that was probably an unspoken rule between them. There were moments when Richie wanted more, he could see himself getting better and becoming embedded within the team. In many ways Richie was more dedicated to the technical aspects of car development and would stay the whole winter over in Italy. He was much more prepared going into the 1961 season and more familiar with the car than my father.

When they got to Monaco, Richie was given the new unproven latest engine development in the 120 degree motor. He proved his speed right away and was the fastest of the Ferrari teammates in that race. But I don’t think he could maintain that high pace of performance, and my father could. Their relationship remained very good until a few years later when it started to dissolve a little during the Ford years. Richie had his own big ambitions and hated playing second fiddle.

That season was nip and tuck between Trips and my father. Wolfgang had physical issues that hindered him sometimes, a diabetic problem. I think he learnt to manage it and still maintain a high performance, but he blew a little hot and cold. He was nowhere at Monaco and had a terrible weekend, while Richie and my father were right there battling it out and trying to keep up with Stirling Moss.

After a weekend like that my father must have thought he was looking good for the championship. But then at Zandvoort Trips won. This was where my father struggled with the idea of team orders. He had this idea of loyalty pounded into him. At Zandvoort, the crowd of German spectators coming over for the race meant: “Phil, it’s Trips’ turn”. My father had the pace to win at Zandvoort, but he was still trying to play along with this game to nowhere.

It was really back and forth between them that year and Trips obviously had the speed when you look at the qualifying times. But I still think my father had the edge and it was really his championship to lose.

Derek Hill says the shoot with the 156 at Reims and also at Zandvoort was an emotional experience. Racing brought him closer to his father before Phil became ill and died in 2008

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Monza was the defining moment of my father’s career. It wasn’t just the race, it was the whole lead-up to it, not knowing who the team wanted to win or whether they were neutral. The tension between him and Trips was so high at that point because they both knew they had an equal chance of winning, and in fact Trips had a slight lead of four points. The things that Enzo Ferrari said to him in practice and the fact that the car was not put together well, with a gearbox that was out of sorts and an engine down on power, my father had to advocate for himself like never before within his own team. And I think the team was stuck in the same place with orders from Ferrari, yet they really liked my father, who had established such a tight-knit relationship with them. There were all these forces at play – and then we know how the race played out. It was the greatest moment of my father’s career and it was also the worst, all at the same time. To think of all those conflicting emotions coming at him all at once – it must have been very difficult.

“It was the greatest moment of my father’s career, and the worst”

A few years later he helped advise on the Grand Prix movie, with a James Garner character much like himself and a script at Monza that had echoes of 1961. I like to go back and watch it because every time you do, you spot something you’ve missed before. At that stage, my father was starting to enjoy life. He couldn’t enjoy his career at the time because he was so highly strung: you are either going to kill yourself or make a mess of things and not achieve what you’ve set out to do… he was by nature an extreme worrier.

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Ernst Schlogelhofer

Ernst Schlogelhofer

It’s hot work driving a 1960s F1 Ferrari, even if it’s just for the cameras. Phil Hill spun out from the lead at Reims in 1961, opening the door for team-mate Giancarlo Baghetti’s historic victory on his grand prix debut

Ernst Schlogelhofer

People can be cruel and while he was congratulated on winning a championship, they tried to get him to question the way he won it himself. But as time went on that was forgotten. He could just enjoy it for what it was, in the history books. He found his place in the world, met my mother, which was a big plus for him, and continued doing what he loved, which was restoring cars and creating a business out of that. Drivers go through a period where they are forgotten for a decade or so after they retire, then all of a sudden nostalgia kicks in and he spent the rest of his life being honoured as a great champion. He rode that wave. It filled his spirits. But he was also respected in other ways because he was a worldly person. He loved England and could really speak to a crowd at the BRDC – he wasn’t some hokey American telling a story. He loved the various cultures he was able to be a part of. I went to the Le Mans 24 Hours with him when I was young and saw how respected he was by the ACO. Going to the Ferrari pits at the Italian GP with him, I felt like I was in the presence of a god… That was a lot of fun.

Don’t hold your breath for the documentary. For me, it has to feel right. In some ways it’s been a detrimental thing for me to pursue this film! There will perhaps be a silver lining if I see it through, but then again we all want these stories to be told perfectly. Like my father I have a bit of that perfectionist mentality which is a terrible thing in terms of getting things done. But it’ll happen.