How F1 rake angles have shaken up the 2021 championship

Floor changes for this year, combined with cost-cutting measures, have shifted F1’s competitive order, says Mark Hughes

Getty Images

From the moment the regulation floor trim of 2021 was announced there were competing theories about how it would affect the low-rake and high-rake cars respectively. The fact that the two low-rake cars – Mercedes and its relative, the Aston Martin – appeared to have significantly lost competitiveness in the opening race at least suggests that the change has favoured the high-rake concept popularised over the years by Red Bull and subsequently followed by most of the others. As such, the small tweak designed to ease the strain on the rear Pirellis may have fundamentally changed the competitive order.

A diagonal line in the outer floor, beginning 1800mm back from the front axle line to a point ahead of the rear tyre, 100mm inboard, defines the cut. In addition, the various slots and holes which previously helped to aerodynamically seal the floor and release the ‘tyre squirt’ air ahead of the rear wheels were outlawed. The vanes hanging down from the rear diffuser (beyond 250mm outboard of the centre line) were cut by 50mm and those attached to the rear brake duct were also heavily trimmed.

The rake angle of the floor helps define how much negative pressure (and therefore downforce) it produces. It’s multiplied by the area of floor. The Mercedes (and related Racing Point/Aston) has always compensated for the lower rake by having greater floor area from a longer wheelbase. So would the floor cut and associated changes hurt the low-rake cars more because the total loss of floor area would be greater (because of their longer wheelbases)? Or would the reduced sealing as a result of the banned slots force the shorter wheelbase cars to lower their rake angles to prevent the airflow stalling and thereby lose out more than the low-rake cars? With all the teams obliged by regulation to retain their 2020 chassis as part of a cost-containment measure in the pandemic they could not design a car from scratch to suit the floor trim regulations.

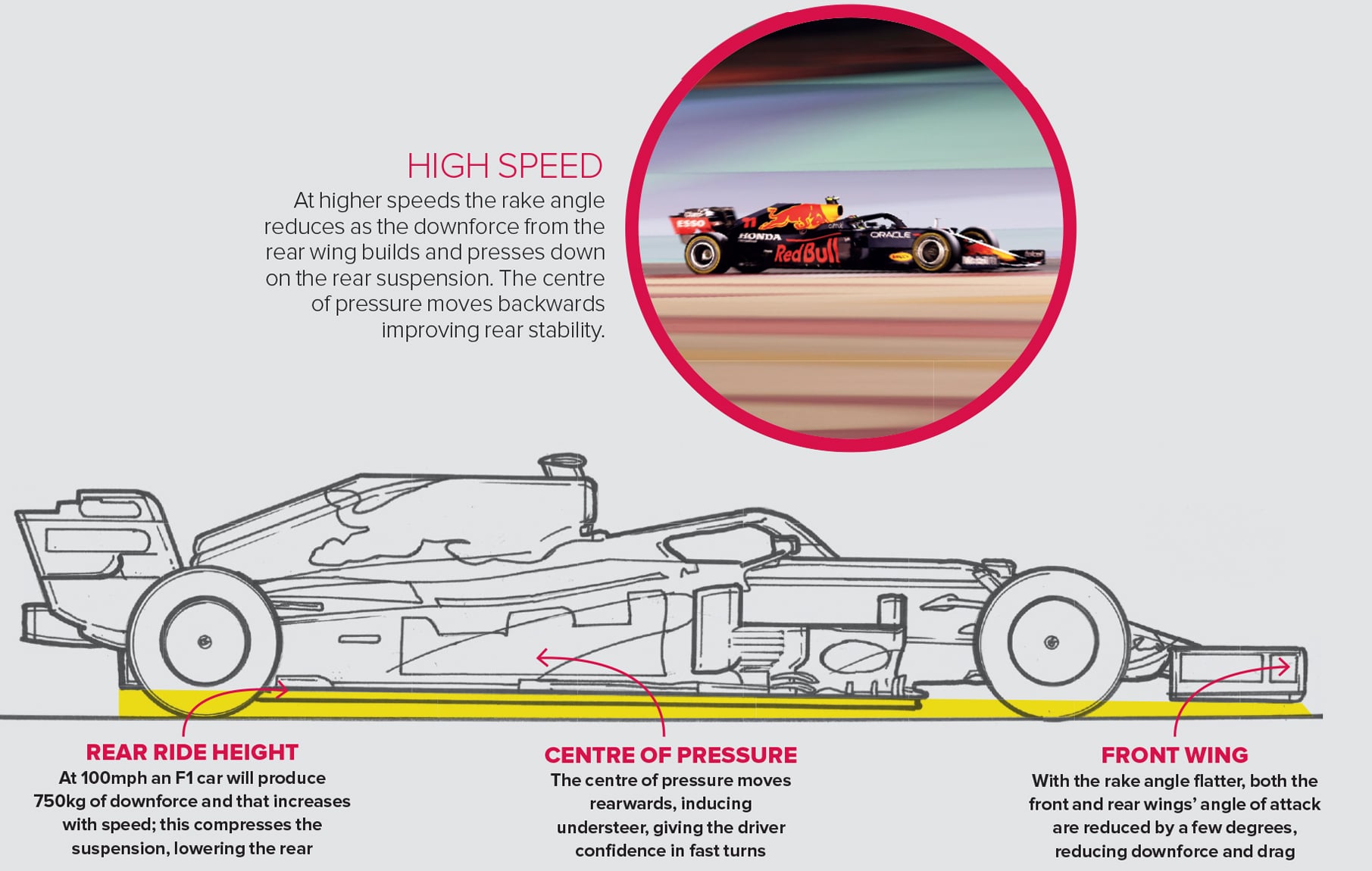

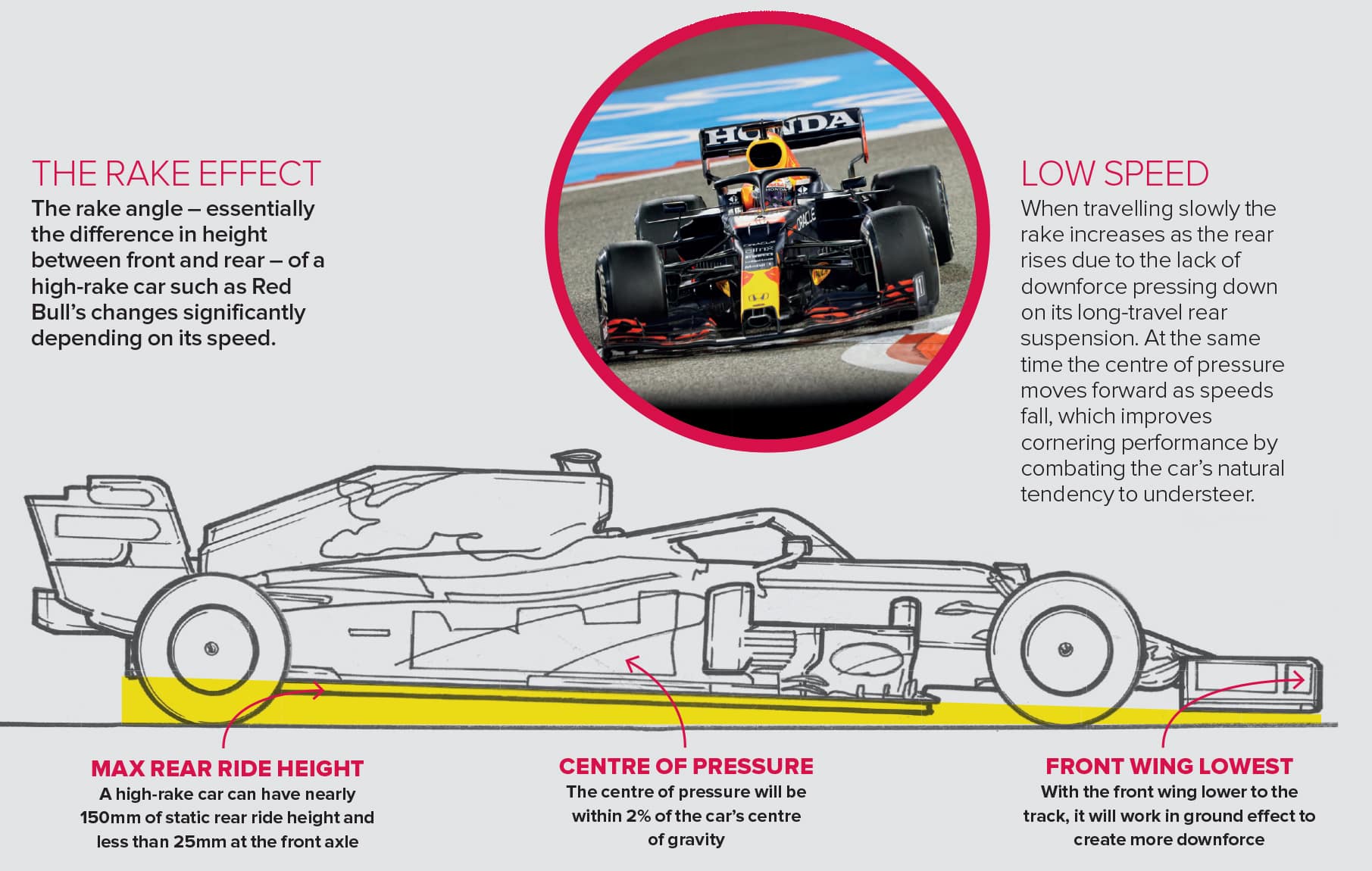

The long, low-rake car has traditionally held an advantage in high-speed corners because the floor area becomes the defining difference as the high-rake car’s rake is reduced by the downforce acting upon the rear, pressing the car down on its suspension. But the high-rake cars tend to have the advantage in slower corners as the more aggressive angle of the floor (and front wing) comes to their aid.

As the drawing above illustrates, the high-rake car isn’t particularly high-rake at speed as its rake is reduced by the downforce (which squares with speed) acting upon the rear of the car, pressing it down on its long-travel rear suspension. But as the speed bleeds off into slower corners and the rear rises, it puts the front wing and leading edge of the floor at a more aggressive angle (increasing the proportion of total downforce generated from the front).

Further, it also increases the expansion ramp of the diffuser (which would normally enhance downforce from the rear, too) but at a certain point when the speed falls enough, the diffuser’s height above the ground makes it impossible to seal effectively and so the front of the car is increasingly favoured as the speed falls.

The rake angle also has an effect on the car’s centre of pressure. This is the aerodynamic equivalent of its weight distribution –a point along its length defined by the proportion of total downforce acting upon the rear wheels and how much is on the front. This point is forever changing according to the speed and pitch of the car, and it will tend to be further forwards at lower speeds. This is a useful trait because a Formula 1 car will naturally tend towards understeer in slow corners but oversteer in high-speed. So the centre of pressure moving the way it does helps combat that.

“There is nothing to suggest Mercedes cannot find a solution”

The effect is enhanced with a high-rake car because with the rake increasing as the car slows, the angle of attack of both the leading edge of the floor and the front wing increases. This helps to put more of what downforce there is onto the front axle.

In testing at Bahrain two weeks prior to the first race there Mercedes found that it had a very unstable rear end. The airflow at the rear of the car was not working as predicted in simulation and was proving very inconsistent. Possibly the floor wasn’t sealing well enough at the rear. This problem was exacerbated by the notoriously gusty tidal winds which affect the Sakhir circuit. As a Band-Aid solution for the first race Mercedes tweaked its setup by reducing the load on the front of the car to at least give Lewis Hamilton and Valtteri Bottas a driveable and consistent balance.

In qualifying, with a car that tended towards understeer – and without the high-rake aggressive centre of pressure migration to help – the Mercedes was losing all its lap time to the Red Bull in turns 5-6 and 9-10. On these two combination corners the front end of the car was surrendering as it was being asked to change from a left-hander to a right (at 5-6) or to further change direction while braking (9-10). At all the conventional corners where the speed is set and the car simply drives through it, the Mercedes was every bit as fast as the Red Bull.

Centre of pressure migration will not be the only reason for the Mercedes’ difficulties at the first race. The distance of the floor from the rear brake duct sited above it will be greater in the low-rake car (as our illustrator Craig Scarborough has pointed out elsewhere) and that duct interacts aerodynamically to direct the airflow around the inner face of the tyre in a way that minimises its interruption to the underfloor. There will be other effects too, and there is nothing as yet to suggest that Mercedes cannot find an aerodynamic solution to the specific problem it has suffered at the beginning of the season.

But the first reading suggests that the reg change has had a competitive impact, not just a performance one.