Lawrence of Arabia's love of speed

The enduring image of Lawrence of Arabia is that of a robed military tactician astride a camel in the desert of the First World War, but as Mat Oxley – whose latest book explores TE Lawrence’s love of motorcycles – explains, the fame-shy soldier and author was a speed freak with a passion for Brough Superiors

The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Soon my speed snapped it, and I heard only the cry of the wind… The cry rose with my speed to a shriek: while the air’s coldness streamed like two jets of iced water into my dissolving eyes. I screwed them to slits, and focused my sight ahead of me on the empty mosaic of the tar’s gravelled undulations.

“Like arrows the tiny flies pricked my cheeks: and sometimes a heavier body, some housefly or beetle, would crash into face or lips like a spent bullet. A glance at the speedometer: 78. Boanerges is warming up. I pull the throttle right open, on the top of the slope, and we swoop, flying across the dip, and up-down the switchback beyond: the weighty machine launching itself like a projectile with a whirr of wheels into the air at the take-off of each rise, to land lurchingly with such a snatch of the driving chain as jerks my spine like a rictus.”

Every bike ride was a race to TE Lawrence, aka Lawrence of Arabia, Britain’s greatest First World War hero and one of its most brilliant authors. TEL was also motorcycling’s greatest icon of the first half of the 20th century and wrote some of the finest stories about the thrill of riding motorcycles.

Lawrence never contested an Isle of Man TT, but he was keen to have a go around the Mountain circuit. “I’d thoroughly enjoy the ride,” he wrote to George Brough, who contested the 1913 Senior TT.

There was one great hindrance that prevented TEL from transforming his addiction to high-speed riding into competitive action. “One of the penalties to fame is that you mustn’t lose,” he added in the same letter. “Once in, you’ll have to win it.”

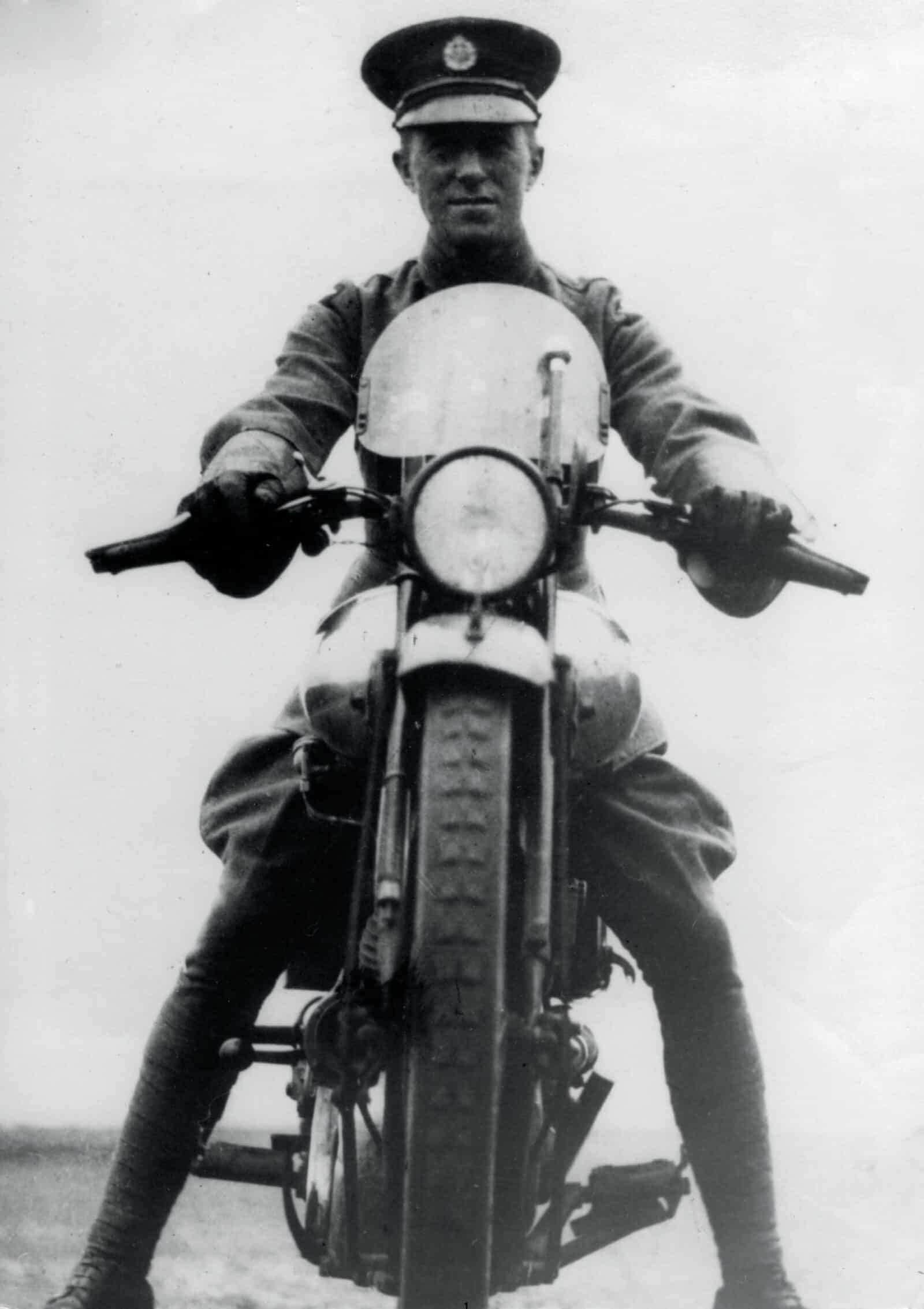

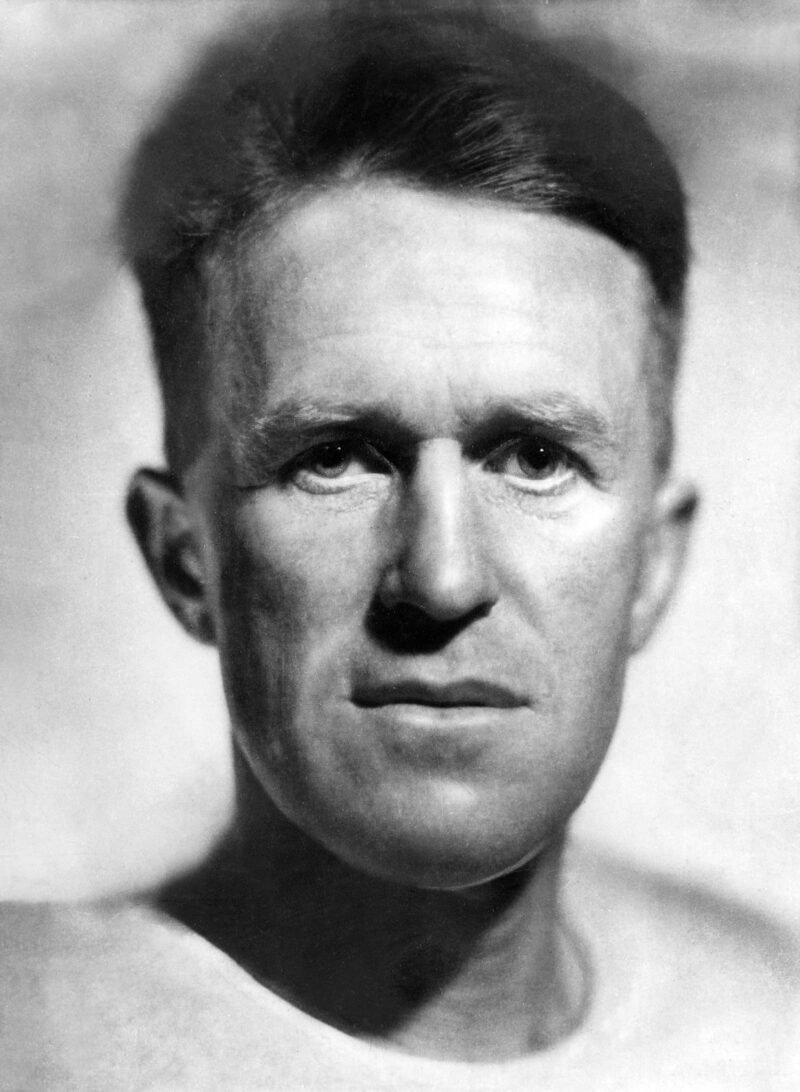

Photographed here around his 40th birthday in 1928, Lawrence had no desire for the trappings of fame and had joined the RAF to be closer to working people

ullstein bild via Getty Images

Lawrence made his name when he fomented, organised and led an Arab revolt against the Turkish army’s rear, using fast-moving guerrilla tactics to disable one of Germany’s key allies. He rode his first motorcycle while in the Middle East, which the locals called a “devil horse”.

His heroic wartime exploits were recorded by American journalist Lowell Thomas, who travelled with Lawrence and turned his story into several books and the world’s first multimedia exhibition. Lowell said he had been looking for a new Richard the Lionheart and he found him in Lawrence, whom he called “a modern Arabian knight”.

Britain needed a romantic war hero in the chill aftermath of the war. It was difficult to find any military glitter in the bloody squalor of the Somme, but here was Lawrence, wearing dazzling white Arab robes, his jambiya dagger glinting in the desert sun.

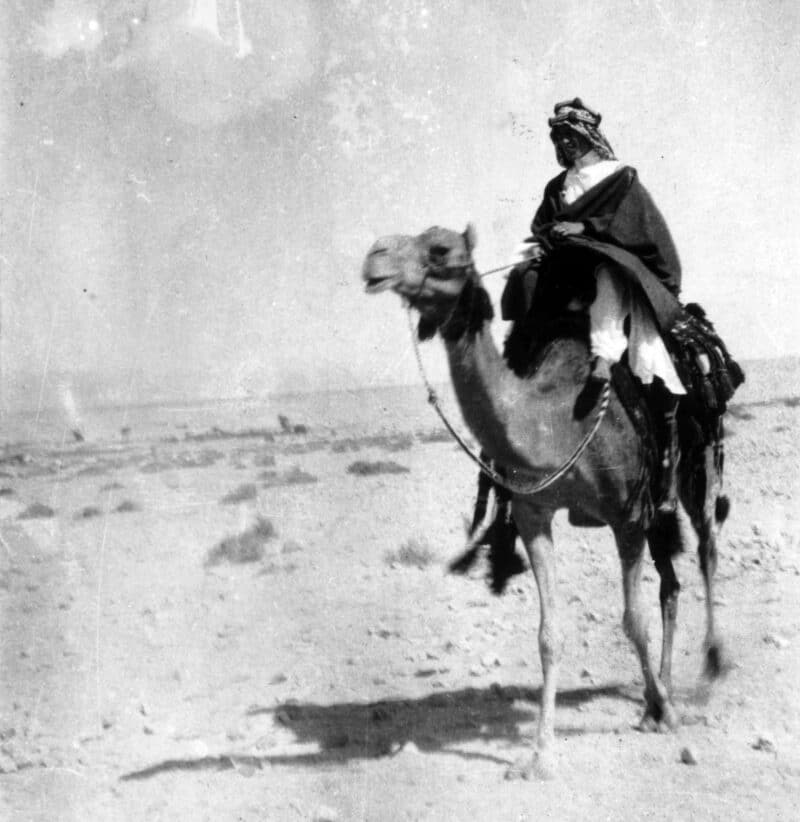

Opposing the Ottomans at the Battle of Aqaba, 1917

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Lawrence later wrote his own book about his war, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which told the story of vicious hand-to-hand skirmishes and supremely brave commando-style raids on Turkish troop trains and supply columns. These expeditions laid the foundations of modern guerrilla warfare, used by everyone from the SAS in the next world war and the Vietcong in Vietnam.

Lawrence pioneered the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and became so adept at laying lethal charges that his Arab friends nicknamed him ‘Emir Dinamit’. Here were the first signs of his engineering genius, which would later become a dominant theme in his life, with his bikes, planes and speedboats.

“One day someone may draw the close parallel that must link his desire for art, his engineering and his whimsical invention with that of Leonardo da Vinci,” wrote Vyvyan Richards in Portrait of TE Lawrence.

Seven Pillars recorded “what is probably the last of the picturesque wars”, according to fellow author EM Forster. “Camels, pennants, the blowing up of little railway trains by little charges of dynamite – it is unlikely to recur. Next time the aeroplane will blot out everything in an indifferent death…”

“One of the penalties to fame is that you musn’t lose”

The 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia was based on Lawrence’s book Seven Pillars of Wisdom

The book further increased his renown, but he hated fame so much that he resigned from the Colonial Office, where he was adviser to Winston Churchill on Arab affairs, then changed his name and enlisted incognito as a lowly airman in the RAF. He was disillusioned with politics and wished to become nothing more than “a small cloud of dust on the horizon”. To that end he bought his first motorcycle, “an old crock of a Triumph”.

“Lawrence loved his Broughs so much that he gave them names”

One of the most mystifying and charismatic figures of the 20th century, Lawrence’s postwar military career lasted 13 years, during which he indulged his love of all things mechanical. He worked on planes, boats and motorcycles. Beyond literature, archaeology, and his desert adventures, motorcycles were perhaps the greatest love of his life.

His tastes in motorcycling, as in most things, were particular. He bought his first Brough Superior not long after returning from his post-war efforts to further Arab independence at the Treaty of Versailles. It was the first of eight machines bought from the upmarket Nottingham manufacturer.

The mighty V-twins were the superbikes of the day, with huge, loping performance and a chassis built for speed. George Brough’s flagship SS100, favoured by Lawrence, was the perfect machine for storming down bumpy, unpaved roads at crazy speeds.

With George Brough, creator of his beloved motorcycles

Lawrence loved his Broughs so much that he gave them names. Collectively they were called Boanerges, a Biblical name meaning Sons of Thunder. Individually, they were christened George I, II, III, IV, V, VI and VII. He also liked to anthropomorphise his machines. “Because Boa loves me he gives me five more miles of speed than a stranger would get from him,” he wrote.

“Never before has Boa gone better,” he wrote to friend George Bernard Shaw, author of Pygmalion and Man and Superman. “I kept on patting him, and opening his throttle… Never have I had anything like him.”

The pleasure he took in motorcycling was evident from the moment he climbed aboard his Brough, according to artist friend Eric Kennington. “His confident ease as he sat astride the monstrous bicycle. A few vigorous kicks on the pedal: the beginning of slow movement: a chuckle: a downward glance, and a sensual grip of the rubber handles – like a cat taking its pleasure in claw-stretching: a conscious summoning of power, still latent in the machine… the head was raised, the eyes gazed at the horizon as if in ownership: the advance quickening snake-like, then the disappearance in a roar of dust. He was happy. He never looked back. Travelling twice as fast as his boats – nearly as fast as his brain.”

Sir Basil Liddell Hart, one of Lawrence’s many biographers, assessed his subject’s lust for velocity thus: “To TE this sensation of speed is entirely exhilarating, because it seems to free the spirit from the bondage of human weakness, and also, I think, because it suggests the power to overcome impediments that nature and human nature place in the way of all achievement…”

Lawrence used his Broughs for everything: for journeys the length and breadth of Britain, for madly fast runs from his RAF base to London and back in the same afternoon, for doing runners from the police and for visiting friends, who included Winston Churchill, writers Shaw, Thomas Hardy, John Buchan and Siegfried Sassoon, composer Edward Elgar, artists Kennington and Augustus John, and socialite Nancy Astor, Britain’s first female member of parliament.

Churchill worshipped Lawrence and, most unusually, was moved to silence whenever Lawrence held forth during visits to the Churchill family home. “I was under his spell, and deemed myself a friend,” wrote the future prime minister. “Sometimes he would stop on his motor bicycle at my house, and I would make haste to kill the fatted calf.”

Lawrence with his jambiya dagger, which was given to him in 1917 after the Arabs’ victory at the Battle of Aqaba

Lawrence adored riding, although speed was the thing. Indeed by all accounts he was a maniac. “I’ve got an extravagant motorbike,” he wrote to a friend in 1923, not long after purchasing his first Brough. “It’s as fast as a hurricane and I hurl over south-west England on it, pleasing myself at every sharp bend and bad place… and to be anonymous and out of sight and very speedy isn’t a bad state. The greatest pleasure of my recent life has been speed on the road. I lose detail at even moderate speeds, but gain comprehension. When I used to cross Salisbury Plain… I’d feel the earth moulding herself beneath me. It was me piling up this hill, hollowing this valley, stretching out this level place; almost the earth came alive, heaving and tossing on each side like a sea. That’s a thing a slow coach will never feel. It is the reward of speed. I could write for hours on the lustfulness of moving swiftly.”

Dressed in a black rubber minesweeping suit in foul weather but more usually in his RAF uniform, Lawrence took great delight in terrifying dawdling car drivers. He wrote the following after a ride from Edinburgh to London, in a letter to Shaw’s wife Charlotte.

“After a mile or two I said to Boanerges ‘we are going to hurry’ and thereupon I laid back my ears like a rabbit and galloped down the road. Traffic this morning was mainly Morris Oxfords, doing their 30 up or down. Boa and myself were pioneers of the new order. Like all pioneers we incurred odium. The Morris Oxfords were calculating on other traffic doing their own staid 40 feet a second. Boa was doing 120 [about 80mph]. While they were thinking about swinging off the crown of the road to let him pass, he had leapt past them, a rattle and roar and glitter of polished nickel. They waved their arms wildly in protest. Boa was round the next corner, or over the nexthill-but-two while they were spluttering.”

On other occasions he enjoyed playing games with the cops. “George VII is running like stink. If you’d seen me dropping the county mobile police last weekend, one by one along the Forest roads, you’d have been pleased with our performance,” he wrote to Brough.

“At his last home he had ‘Why worry?’ engraved above the door”

Lawrence never did get to go racing, but those who rode with him swore there were few better in Britain. “He was one of the finest riders I have ever met,” wrote Brough, who raced at Brooklands and once held the motorcycle land-speed record, albeit only unofficially. “When the road was clear ahead, it took a very good and experienced rider to keep anywhere near TEL.”

Lawrence was certainly one of the first members of the ton-up club, happily clocking over 100mph as he roared through the British countryside. He thought nothing of leaving the Army camp in Bovington, Hampshire, on a Sunday morning, visiting Wells Cathedral (medieval architecture was another fascination), swimming at Land’s End, taking tea in St Ives and then racing back to camp in time for roll call; a round trip of 440 miles.

It was during these wild rides that he established his own kind of lap records.

“Yesterday fatigues for us ran short at 10am: so I leapt for my bike and raced her madly up the London road: Wimborne, Ringwood, Winchester, Basingstoke, Bagshot, Staines, Hounslow by 1.20pm; three hours less five minutes. Good for 125 miles: return journey took 10 minutes less!”

This 1932 Brough Superior SS100, GW 2275, was the motorcycle Lawrence was riding when he was killed. After the crash, the bike was repaired by Brough and is now privately owned

Lawrence certainly rode to forget the war, which claimed two of his five brothers, and the things he had done during the war, most especially his decision to shoot his Arab servant boy, Faraj, who had been badly wounded by the Turks.

“To him speed was rest, as it is for many people nowadays,” wrote Clare Sydney Smith in The Golden Reign, a record of her friendship with this great Briton. “At times his impulse was to run away from life.”

Often it was his life in the ranks from which he wanted to escape. “My motorbike is called into use when I find myself on parade facing a sergeant with my fists hard clenched. A hundred fast miles seem to make camp feel less confined afterwards.” And in another letter, “riding chases off the broody feeling”.

Brough Superior ‘George V’ RK 4907 was new in 1927. Around 3050 motorcycles were built by the Nottingham company from 1919-40

Shutterstock

It would seem that risk was essential to Lawrence’s being: he needed to go to the very edge and face the possibility of going over it. At his last home, Clouds Hill, a cottage near Bovington camp, he had the words “Why worry?” engraved above the front door. In Greek, of course.

“I’ve tried for a valiant six weeks to do without a motorbike”

Lawrence’s most famous piece of writing on bikes formed a chapter in his book The Mint, which tells of his gruelling years in the ranks, during which he used the name John Hume Ross. The chapter titled The Road tells the tale of his race with an RAF fighter plane.

“Once we so fled across the evening light, with the yellow sun on my left, when a huge shadow roared just overhead… A Bristol Fighter… The pilot pointed down the road towards Lincoln. I sat hard in the saddle, folded back my ears and went away after him, like a dog after a hare. Quickly we drew abreast… The next mile of road was rough. I braced my feet into the rests and clenched my knees on the tank till its rubber grips goggled under my thighs. Over the first pothole Boanerges screamed in surprise, its mudguard bottoming with a yawp upon the tyre. Through the plunges of the next 10 seconds I clung on, wedging my gloved hand in the throttle lever so that no bump should close it and spoil our speed. Then the bicycle wrenched sideways into three long ruts: it swayed dizzily, wagging its tail for 30 awful yards. Out came the clutch, the engine raced freely: Boa checked and straightened his head with a shake, as a Brough should. The bad ground was passed and on the new road our flight became birdlike… I dared, on a rise, to slow imperceptibly and glance sideways into the sky. There the Bif was 200 yards back.”

Lawrence’s adoption of robes furthered his reputation

Lawrence’s second stint in the RAF was the next step in his hopes of transforming his life “from ink to oil”, so he could live with everyday people, away from the glitz of uppercrust gatherings and the gaze of what we now call the paparazzi, who were always after him.

A fast-throbbing engine always gave him more pleasure than social chit-chat. “He was exulted by the sound in the early morning of the running up of a 260 horsepower Rolls- Royce engine at 1900 revs,” wrote Andrew Simpson in Another Life: Lawrence After Arabia.

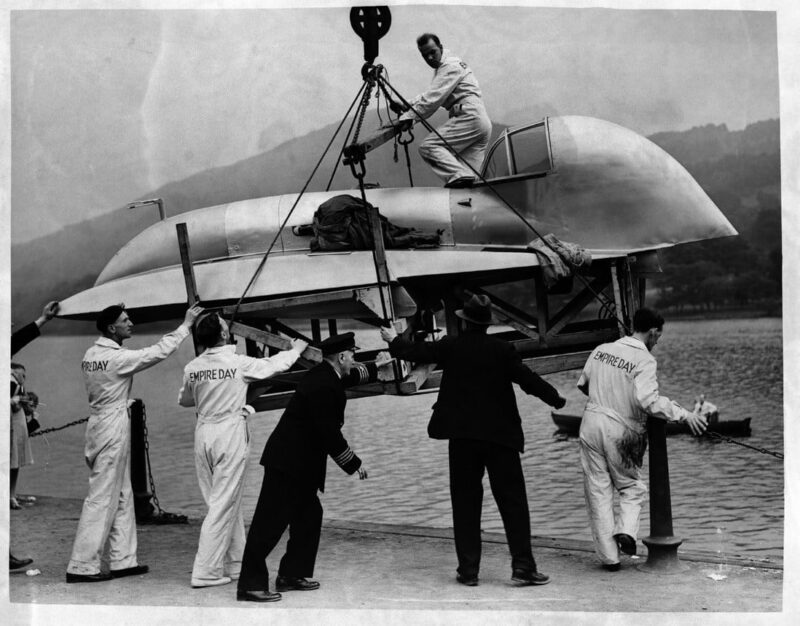

Lawrence’s love of speed also included water vessels. The Empire Day hydroplane, was designed by Lawrence and engineer Edward Spurr and is being lowered into Lake Windermere in 1938 for trials. It reached 73mph but was damaged by fire

During this stint in the RAF he helped maintain Bristol fighters. He deeply appreciated working as a mechanic, getting to the very heart of his love affair with the internal combustion engine.

“I am now a fitter,” he wrote. “Very keen and tolerably skilled on engines. I live all of every day with real people. The ancient selfexamining TEL is dead.”

On several occasions he tried to do without a motorcycle because he wanted to live in poverty, but he found it difficult to get through life without a ride. “Being without a Brough Superior is a narrow and sorrowful life,” he wrote to Brough. And this to another friend, “I’ve tried now for a valiant six weeks to do without a motorbike… and I find that it was indeed the safety valve I’d thought. So I’m going to get a new one.”

Lawrence spent much of his income on bikes. Whenever a book advance fee landed in his bank account, he would write a cheque. “Brough has brought out a new and most wonderful ’bike, which will do 112mph, so long as the tyres will stand it,” he wrote in 1925. “I’m going to blow £200 of Cape’s on that.”

Four years later he was appointed assistant to the leader of the RAF’s High-Speed Flight. This group prepared planes for the Schneider Trophy, the world’s most prestigious international air race and the fastest, most glamorous race of the age.

Lawrence was as thrilled as anyone by the British team’s 1929 Schneider victory. “You should see Boanerges when he really goes!” he wrote at the time. “Almost like a Schneider Cup machine.”

Taking a back seat in Transjordan, 1921. Lawrence was part of a meeting between Arab, Bedouin and British officials, where British high commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel proclaimed Amir Abdullah as the ruler of Transjordan

Lawrence died in May 1935 aged 46. Two boys were riding bicycles on the wrong side of the road, Lawrence came over a brow, swerved to avoid them and crashed heavily, fracturing his skull. He wasn’t wearing a helmet. He died six days later, without regaining consciousness.

His own death wouldn’t have come as a surprise to him. He often joked with friends about the dangers of his obsession with speed. “The bike is a man-killer,” he wrote to George Bernard Shaw. “I’m afraid to death of it.” When another admirer took one look at his Brough Superior and said, “You will be breaking your bleeding neck on it,” Lawrence laughed and replied, “Well, better than dying in bed.”

And perhaps he even foresaw his own demise on a motorcycle. “In speed we hurl ourselves beyond the body,” he wrote. “Our bodies cannot scale the heavens except in a fume of petrol.”

Lawrence of Arabia was buried at nearby Moreton Cemetery. His funeral was attended by many of the most eminent Britons of the age. Churchill openly wept during the service.

Churchill summed up Lawrence’s restless nature and his difficulties with coming to terms with normal life after his wartime experiences. “He was one of those beings whose pace of life was faster and more intense than what is normal. Just as an aeroplane only flies by its speed and pressure against the air, so he could only fly in a hurricane. He was out of harmony with the normal and when the storm-wind stopped, he could with difficulty find a reason for existence.”

If Lawrence’s death was a tragedy, some good did come out of it. While he lay unconscious in the military hospital at Bovington camp he was visited by the King’s physician, Sir Farquhar Buzzard, and by Australian neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns, assistant surgeon to the London Hospital. Neither could do anything for Lawrence but Cairns was inspired to do something to prevent further motorcycling deaths.

In 1941 he published the first real research into head injuries in motorcyclists. By then the Second World War had already claimed 2279 motorcyclists, two-thirds of them as a result of head injuries. Many of these accidents happened during night-time blackouts, introduced during the Blitz.

Cairns’ findings promoted the importance of the crash helmet and initiated compulsory helmets for all military personnel riding motorcycles. This regulation saved several thousand lives during the final years of the war. His research eventually led to the 1973 introduction of compulsory helmets for all road riders in the UK.

Lawrence’s damaged motorcycle is unloaded at the hospital of Bovington Camp in Dorset in 1935, before an inquest into his death