This Coventry Climax FW – for ‘Feather Weight’ – won a Home Office order for 5000 engines. The company had a stand in the marine section of the 1952 Earl’s Court Motor Show, where Wally and Harry met many old racing friends. John Heath of HWM, Rodney Clarke of Connaught and Cyril Kieft all wrote to Lee, imploring him to build them a new 2½-litre F1 engine. He agreed, so Hassan and Mundy produced the Climax ‘Godiva’ V8 only to take fright at Ferrari and Maserati’s power claims, causing the project’s unraced demise. Kieft, then Cooper and Lotus, focused instead upon the little single-cam Climax FW, for 1100cc sports car racing. Stock-block MG and Ford units were fragile and costly, once race-tuned. Responding again to demand, Lee directed Hassan and Mundy to adapt the FW.

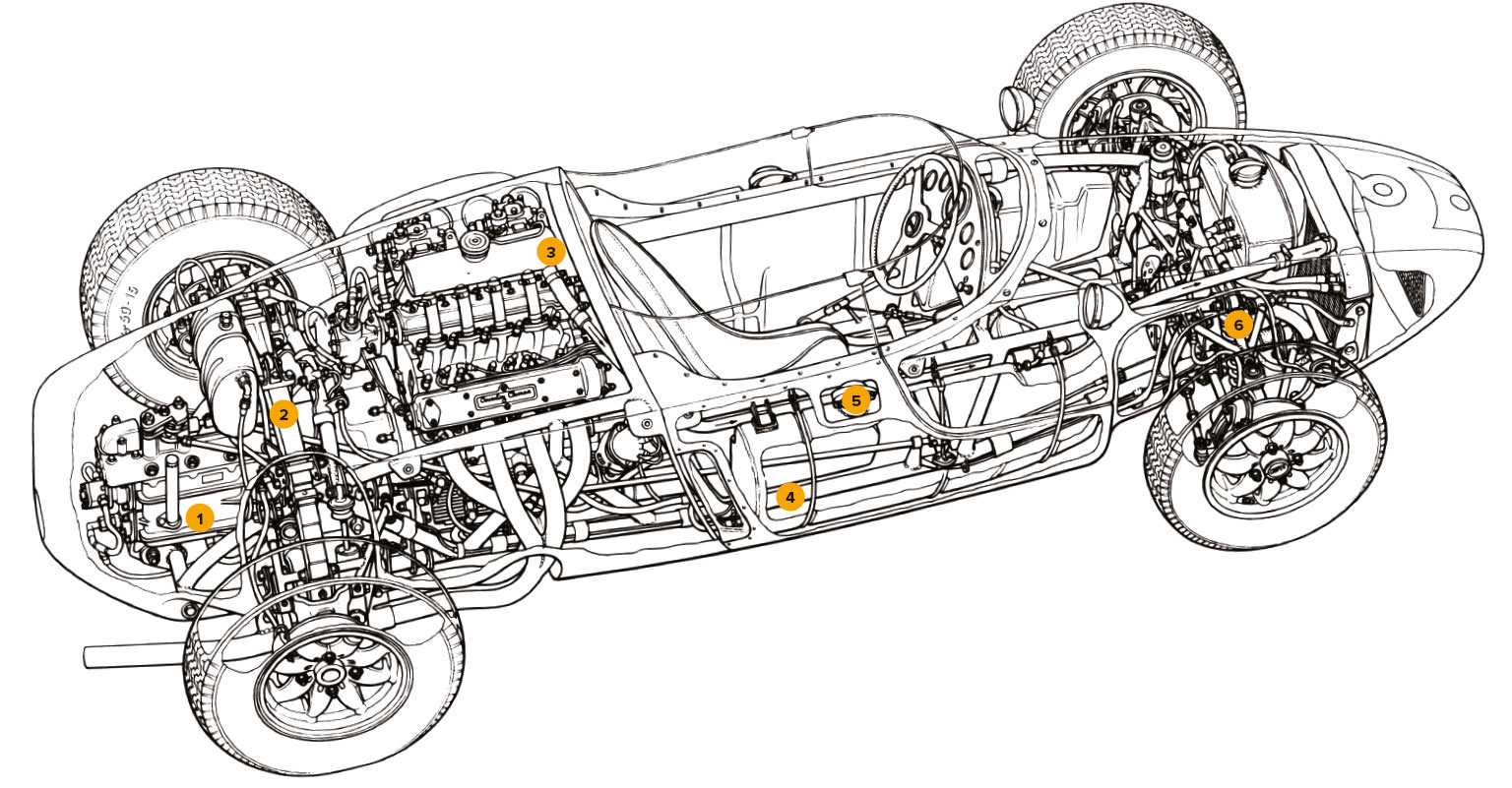

The standard Climax FW engine displaced 1020cc. The ‘FWA’ – short for ‘Feather Weight Automotive’ – was overbored to 1098cc. In mid-summer 1954 the first FWA powered the Alan Rippon/Bill Black Kieft at Le Mans. Climax began small-scale FWA production – and Cooper used it, rear-mounted, in its new ‘Bobtails’. With only 75bhp available, the target 125mph demanded minimum weight and frontal area. The ‘Bobtail’ Cooper’s sleek bodywork wrapped a 65lb tubular chassis with transverse leaf-spring suspension front and rear. F3 tuner Francis Beart suggested a Citroën Traction Avant gearbox turned about-face to drive the rear wheels, with close-ratio gears and shafts made by ERSA of Paris, who marketed a popular four-speed conversion of Citroën’s standard three-speed ’boxes.

The ‘Bobtails’ became a huge force in 1100cc – and later 1500cc – sports car racing. Using the factory jig, Australian newcomer Jack Brabham built an F1 special along ‘Bobtail’ lines – using a six-cylinder Bristol engine under lookalike ‘Bobtail’ bodywork. He made his F1 debut in it at the 1955 British GP, and won the Australian GP.

Bruce McLaren’s grand prix debut at Nürburgring in F2 Cooper at ’58 German Grand Prix

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Seven prototype 1100cc FWAs were delivered through 1954, followed by 100 for 1955 and more in 1956, plus 24 enlarged 1460cc 100bhp FWBs, while Hassan and Mundy were developing a twin-cam heads for ’57. A few pilot 1500cc F2 races ran in 1956. Cooper dominated – and for international F2, 1957-60, the new dry-sump, twin-OHC Climax FPF became available. Schemed largely by Mundy, then developed by Hassan, Peter Windsor-Smith, Gray Ross, Ron Burr and Hugh Redington, the FPF had five main bearings against the FWA/FWBs’ three – and developed 141bhp at 7000rpm. F2 Cooper-Climaxes were quickly dominant.

The 1957 F2 Cooper was the Type 43 or ‘F2 Mark II’ design – with all-transverse leaf-spring suspension. Famously, during Goodwood testing, works driver Roy Salvadori suggested to John Cooper and private entrant Rob Walker that such a chassis fitted with an enlarged FPF engine would be ideal at Monaco. “It was so agile I thought it really could compete there…” He was right. Jack Brabham drove the 1.96-litre ‘interim F1’ Walker Cooper there – ran third and finally pushed the broken car home sixth. Such little ‘2-litre’ hybrid Cooper-Climax cars raced on in F1 that year. And few amongst the front-engined establishment foresaw their threat…

What advantages did rear-engined configuration offer? With no propeller-shaft to pass beneath – or around – the driver, he (or she) could sit lower, minimising the car’s frontal area. Power-wasting prop-shaft angularities – and weight – were saved. One square foot less frontal area was considered worth 25bhp. With engine and final-drive mounted in-unit, torque reactions cancelled out, permitting lighter support structures. Lighter weight enhanced acceleration, permitted smaller brakes – and so on in an always-beneficial spiral. Concentrating a car’s major masses within the wheelbase promoted rapid direction-change response. Without the extravagant power excess of the 1930s cars – in which drivers could change the car’s attitude by breaking rear tyre adhesion – Cooper-Climax agility could outrace most front-engined rivals.

For 1958, an FIA rule change helped. While the 2½-litre F1 ceiling was extended to 1960, alcohol fuels were banned and replaced by 100/130-octane AvGas aviation spirit. Simultaneously, grand prix race distances were slashed from a minimum of 500km/three hours to only 300km/two hours. Fuel consumption on AvGas was inherently better than on methanol, so even without the shorter races, fuel tank capacity would still be reduced. Cars could now be considerably smaller and lighter – yet the Coopers already were, and their engines were also outstandingly economical…