Lunch with... Norbert Singer

For 40 years he was the architect of Porsche’s sports car racing success all over the world. But one race always mattered more than any other

James Mitchell

The earliest use I can find in print of the expression “Racing improves the breed” dates from 1835. It refers, of course, to racehorses: breeding from winners could produce more winners. The first time it was applied to cars seems to have been in 1908: “Just as horse racing improves the breed of horses, so do automobile races improve the quality and construction of (everyday) motor cars.” Le Mans certainly made this true of the 1920s Bentleys, for example, and in the 1950s it hastened Jaguar’s disc brakes and Mercedes’ fuel injection.

Today the cliché is trotted out more than ever, but it is far less true. Road car development can be more rapidly and cost-effectively achieved behind locked doors, away from the prying eyes of competitors and the public, and motor racing has taken on the more disparate role of marketing the brand. Today it’s “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday.”

But for a handful of car manufacturers through the 1970s and into the ’80s, motor racing was a major driver of technical development. Marketable fame was secondary. There is no better example of this than Porsche, and no better proponent of it than Norbert Singer, who spent more than 40 years developing and directing racing Porsches.

His involvement spanned an extraordinary 16 Le Mans victories in 29 seasons.

Singer discusses tactics with engineer Walter Naher

Motorsport Images

Norbert is 75 now, and lives not far from Zuffenhausen, the northern suburb of Stuttgart that is home to Porsche. He has not quite retired: poacher turned gamekeeper, he is a consultant to the Le Mans 24 Hours organisers. I meet him at his favourite Strohgäu restaurant in Münchingen for veal cordon bleu and crêpes suzettes: a friendly, good-humoured man, but modest. He tells his tales as from a team, not an individual.

Norbert’s original ambition was to be a rocket scientist, but during his university engineering course he found he had the wrong passport. Americans build spaceships, he was told; Germans build cars. But cars, and particularly racing, also fascinated him.

“In 1965 a friend of mine and I got ourselves to the Nürburgring Nordschleife to watch Jim Clark’s Lotus 33 win the German Grand Prix. But on that circuit you only saw the cars pass 15 times, and I knew that at Monaco they did 100 laps. So in 1967 we drove my old Opel Kadett all the way there. By dawn we’d made sure of our place by the track, and it was fantastic. But that was the year poor Lorenzo Bandini lost his life, and after that the race was cut to 80 laps.

“After university I planned to join Opel, because they offered new engineers two years with General Motors in Detroit. But when I heard that Porsche was looking for a youngster in its racing department, I applied. My father was horrified: ‘Porsche? A small company like that? Borgward is gone, Glas is gone, BMW is in trouble. How long can Porsche last?’

“After my interview with Porsche in February 1970 they said they would write to me. But I heard nothing. On Monday March 2 they phoned: ‘Why are you late for your first day at work?’ They had forgotten to send the letter. I rushed to Stuttgart and found digs, and on Tuesday morning I was in the little racing department. It was 14 weeks to go to Le Mans. I was the new boy, and at once I was told to rethink the fuel system. The Porsche had a long, narrow tank, and everything sloshed back and forth under acceleration and braking, requiring several heavy suction pumps. I made up different baffles and reduced the pumps.

Tail variations were a theme of the 917 at Le Mans

Motorsport Images

“The 917’s real weak point was the gearbox, which had no oil radiator and had to be cooled by the air spilling around it. As the ambient temperature went back up on Sunday morning the oil would overheat. Make it run cooler, they said, but don’t add any weight.

“Space around the gearbox was tight because of all the chassis tubes, but I designed some larger ducting. There was nobody to make the moulds, so I made them myself with modelling clay I pinched from the styling studio. Then I went with Hans Herrmann to the Nürburgring to test the changes, and it was fine. That was a few weeks after I joined: you could say I had to jump into the deep end of the swimming pool. I wasn’t asked to go to the 24 Hours, but Hans won it with Richard Attwood, so I felt I had played my own little part in Porsche’s maiden Le Mans victory.

“The first time I was actually in charge at a race was the following year, in Austria. Porsche made its own brakes then, and our technical boss Helmuth Bott wanted us to use an ABS system we’d come up with. We tested it a lot and it worked more or less, but with so many mechanical parts it was never going to be right. Today ABS is all-electronic, so it’s completely different. In Austria we ran it in one car, and Gérard Larrousse confessed to me afterwards that he turned it off before the end of lap one.

“More or less by accident, I started to make a speciality of aerodynamics. As a young engineer in a small department you have to be able to do lots of things. I was given the old riddle: reduce the drag without reducing the downforce. In 1969 the long-tail 917 for Le Mans was very twitchy at its highest speeds, so I had to find less drag, more downforce, better balance. Porsche didn’t have its own wind tunnel then, so I used the tunnel at Stuttgart University. I was free to try anything I wanted, and many of my ideas didn’t work, but we learned a lot. Finding speed through aerodynamics is all about changing little details: big steps are more difficult.

“After three or four days of hard work I had improved the drag and stability without losing downforce – we didn’t have a lot of downforce then, of course – and I’d added little tail fins. The key was the Mulsanne kink. In those pre-chicane days, if your drivers could take the kink flat, you had done your job. At the April test weekend Derek said it was now flat for him and Jo Siffert. I asked what revs he was pulling, and he said 8100rpm. I did some slide rule calculations with allowance for tyre growth, and when Derek insisted I told him, I had to say: 396kph. That’s 246mph.

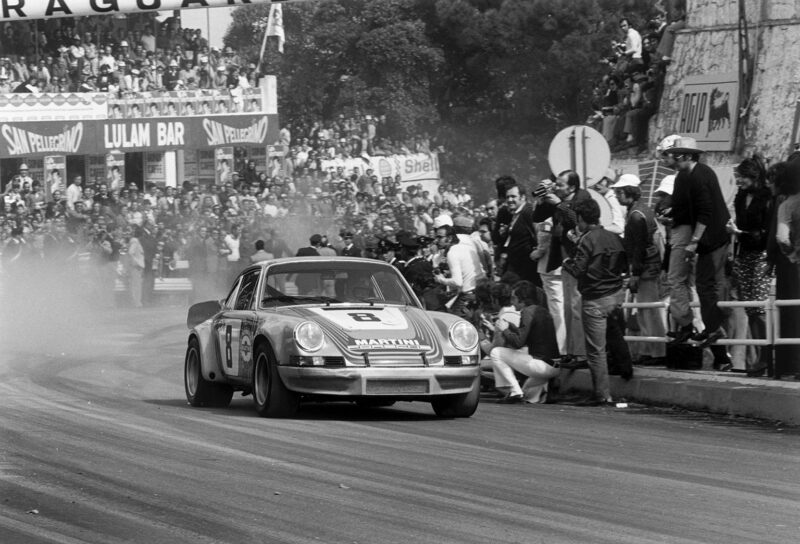

RSR prototype wins 9173 Targa Florio with Muller/Van Lennep

Motorsport Images

“Ferdinand Piëch’s idea with the 917 was to run with two teams, JW Automotive and Porsche Salzburg, to double the chance of victory. John Wyer had been developing his own bodywork too, and Derek and I spent a dark, wet day at Hockenheim comparing three tails: JW’s, ours and the short one as a baseline. We used a speed trap on the long return straight, missing out the infield, and our tail was fastest. It was getting dark as we did the last runs, and Derek was doing nearly 200mph when a man on a bicycle came wobbling across the main straight, obviously taking his daily short-cut home from work. Derek got just a flash of his horror-struck face as he missed him by inches.

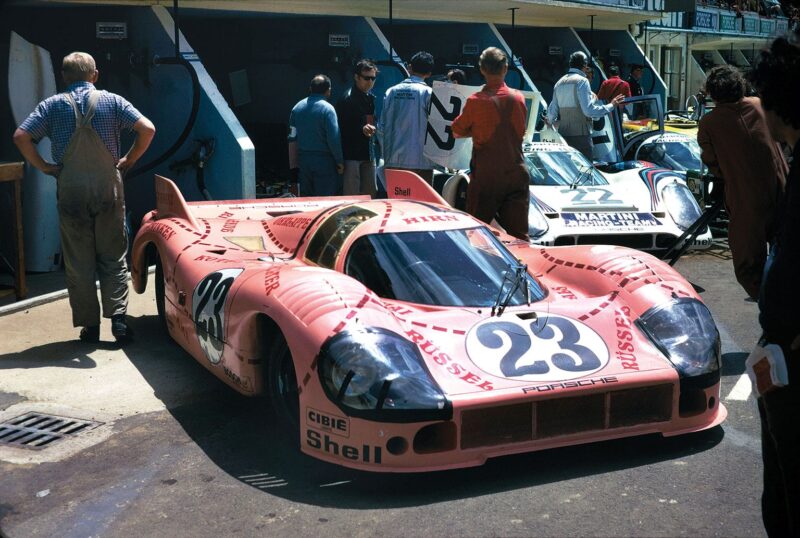

“We also did some aerodynamic work with the French firm, SERA. The challenge was to find a shape with the drag of a long tail and the downforce of a short tail. They made all the bodywork curves of bigger radius, which was good in theory, to keep the vortices down. But although the downforce was OK the drag was worse. The car had a bloated look, and somebody said it was like a pig. So Tony Lapine, our styling boss, had it painted pink with dotted lines and names of pork joints across it like a butcher’s diagram. I don’t know what Dr Piëch thought about it. It retired from its only race, but today it probably attracts more photos in the Porsche museum than any other car.

“We won Le Mans again in 1971, but for 1972 the sports car rules changed, and for the 3-litre limit against the Ferraris and Matras the 908 engine was not powerful enough. The American market was becoming important for Porsche, and Jo Siffert told us about the Can-Am races he’d done in his own 917 Spyder. To take on the McLarens we clearly needed a bigger engine, so we made a flat-16 from two 908 engines. It was unbelievably heavy: the bare crankshaft weighed 33 kilos. Then somebody suggested turbocharging. Turbos had been used in aircraft and ships and other applications but, apart from some unsuccessful American compacts in the 1960s, not much on cars. We worked with a turbo flat-12, which was much lighter than the 16. My aerodynamic brief was: find as much downforce as you can, and don’t worry about drag, because we have a lot of horsepower and the American tracks are twisty.

“Roger Penske ran our car, and that first year the 917/10 had no problems with the corners, but the McLarens still had too much power on the straights. So the engine guys reduced the turbo lag and increased the horsepower, to more than 1000bhp. The rear tyres were 19 inches wide. Once again my task was keep the downforce but reduce the drag, and we adapted my Le Mans tail. Mark Donohue easily won the championship, so the McLaren reign was over.”

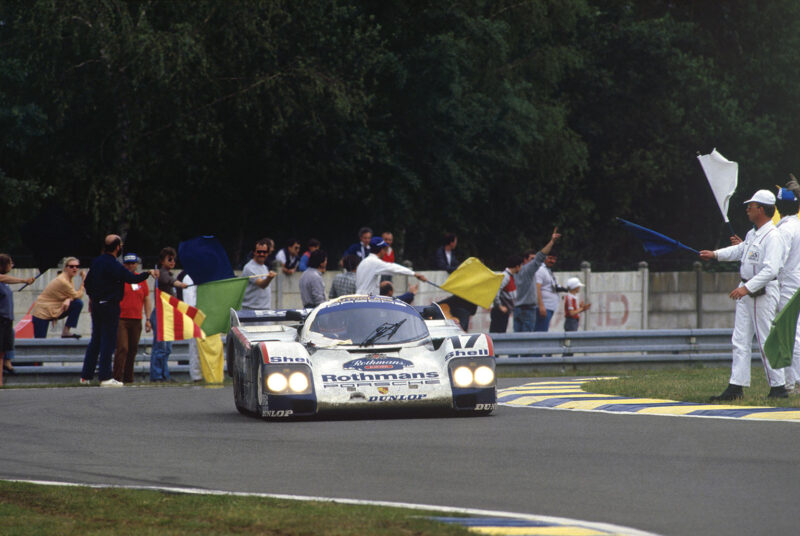

Although Jaguar took the 1987 world title, Le Mans win fell to Porsche 956

Motorsport Images

Norbert was sent to the Daytona 24 Hours in 1973 because two teams were running the 911 which had been developed into a serious racing car, the RSR. “The cars were run by Penske and Brumos. I was introduced as the engineer from the factory. The Penske boys were not impressed, but Peter Gregg of Brumos seemed to take note of my suggestions. In the race all the prototypes retired, and the battle between the two RSRs became the battle for the lead. Then the Penske car lost its flywheel.

Now the Brumos car was on its own, but Gregg was still driving flat out. Bob Snodgrass of Brumos got on the radio to tell him to ease up, but he took no notice. Then Bob hung out a board that read ‘SINGER SAYS SLOW’. Gregg lifted off at once, and he and Hurley Haywood still won by 22 laps.

“The last Targa Florio was the same year, and we ran the RSR as a prototype so that we could try out more modifications. We put 917 brakes on it and a larger spoiler that we called the Mary Stewart, because big pieces came around the sides rather like the neck on the dress of your Mary Queen of Scots. The sports-prototypes from Ferrari and Alfa all had problems, and Herbie Müller and Gijs van Lennep in our lead car won. It was Porsche’s 11th win in the Targa since Maglioli and von Hanstein in 1956.”

By 1976 the road-going 911 turbo was in production – the best example yet of racing improving the breed – and the FIA’s new Group 5 had come in. “That was our best season so far. We ran the 911-shaped 935 in the World Championship of Makes and, when the FIA decided late in the day to institute a Group 6 World Sports Car series as well, we quickly came up with the 936. We won both titles: and our third Le Mans.

“But we were unlucky at Daytona – that’s a race I should tell you about. The 935 of Jacky Ickx and Jochen Mass was leading easily when Jochen had a blow-out on the banking and hit the wall. The right side of the car was smashed, the door was torn off, and it took us an hour to repair the oil cooler, the wastegate and other bits. When we sent him back out with no door, the race officials said we could not race like that. So we borrowed one from a privateer 935 that had retired and slapped that on. Then they said we needed a red rear light. We taped on a pocket torch and smeared the bulb with lipstick borrowed from a girl. The car rejoined in 42nd place, 22 laps down, and Jacky and Jochen went hard at it all night. When the sun came up we were back up to second place, and we were going to win. Then Jochen had another disastrous blow-out on the banking, and this time he could not bring the car home. A private RSR won.”

Norbert has stories from every season, almost from every race. In his lexicon the world championship titles are important, of course, but the actual race wins matter more, and the Le Mans victories matter most of all. The 936 was victorious again in 1977, back-to-back wins for Jacky Ickx, and that year the DRM, the German Championship, had a new contender. “Each DRM round consisted of two separate races, up to and over two litres. We had the over 2-litre races all sewn up, but the under 2-litre class attracted much more interest because it was a big battle between BMW and Ford. So the big boss, Dr Fuhrmann at that time, said, ‘We must do that class too. Make a baby Porsche.’

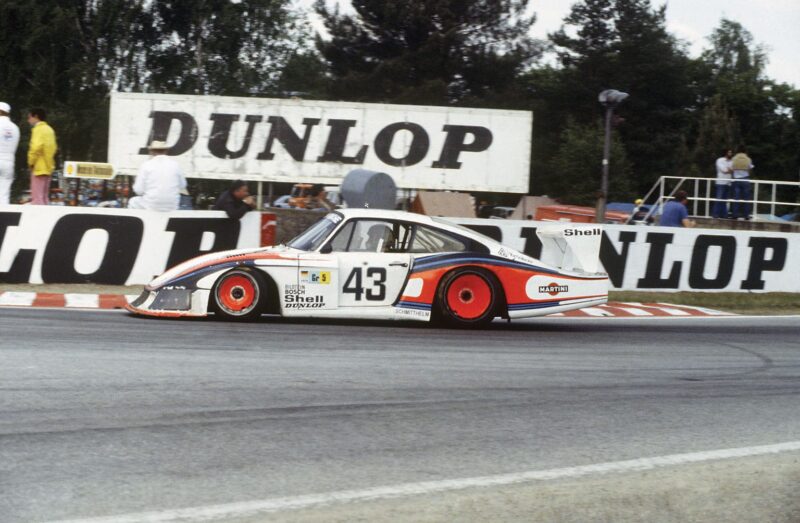

Ultimate 911 – Moby Dick – the 800bhp 935-78

Motorsport Images

“To hit the 1.4 equivalency formula we put together a 1425cc turbo that gave 370bhp, and we built a very light 935 for it. In fact we made it too light, and had to fill some of the chassis tubes with lead to get it up to the limit. It was all done too quickly, and in the first race at the Norisring, in front of 80,000 spectators, the car was slow and Jacky Ickx retired. We decided to do a detailed rethink and miss the next round at Hockenheim. But Dr Fuhrmann wouldn’t hear of it: ‘I don’t care. We go racing.’ So we worked night and day, and we just got to Hockenheim. Jacky took pole by 2.8sec and won by almost a minute. I sent a message to Dr Fuhrmann suggesting I should get a pay rise for this. He said, ‘No, I get the pay rise, because I insisted you go to Hockenheim’.”

The ultimate 935 was the ferociously long, low 935-78. “We got nearly 800bhp out of that. It was the first time we’d used water as a cooling medium. We’d had some head gasket failures, so we welded the heads to the block and just cooled the heads via a water radiator. The rear wheels were 19-inch diameter, 16-inch rims, and the car was 6½ feet wide. When it was in grey primer, before it got its Martini colours, somebody said it looked like a whale, so it was Moby Dick from then on. We only raced it four times, winning first time out at Silverstone by seven laps. At Le Mans, despite its big 911-shape shell, it did 227mph on the Mulsanne. The timekeepers’ lists said only the Renault sports-prototype with its streamlined cockpit canopy was faster, by 1kph, and I expect that figure was political. We were in France, after all. But Moby Dick drank fuel. We were allowed 120 litres tankage, and we could only run 40 minutes between stops. Just as the mechanics finished clearing up the pit, the car would be coming in again – all through the day and night.”

Ickx’s 1977 Le Mans win deserves a special mention over our lunch table. “Our lead 936, Jacky Ickx/Henri Pescarolo, went out when a conrod broke. The No2 car had already retired, and the No3 car seemed totally out of it, having lost nearly an hour in the pits with a blown head gasket and fuel injection problems. It was now in 41st place. So on Saturday evening we put Jacky in. He spent nearly 11 of the remaining 19 hours in that car, including 6½ through the night. He broke the lap record again and again, and by 10am on Sunday he was in the lead.” During that drive, which Jacky said years later was the hardest of his life, he lost more than a stone in body weight.

“Then we stood Jacky down, and the car’s original drivers, Jürgen Barth and Hurley Haywood, took over to drive to the end. We now had a huge lead: but the story wasn’t over yet. In the final hour it came in wreathed in white smoke: blown piston! We took the fuel and spark out of that cylinder, and held the car in the pits waiting for the end of the race. The rules say that the lap time of each of the last two laps has to be within a given percentage of the other, so at 3.52pm we sent Barth chugging out again. We taped a watch to the steering wheel so he could ensure his two laps were roughly constant, and also to avoid crossing the line just before 4pm, which would have committed him to another lap. It all worked out, and that was our fourth Le Mans win.

“Part of our routine at Le Mans was Teloché, the little village south of the circuit, where Porsche always had its race headquarters. We took over the local garage for a week to prepare the cars. All of us (except the drivers) stayed in villagers’ houses, each mechanic going back to the same family every year, and we ate at a long table in the local bar. On Saturday morning we would drive the race cars along the D140 public road to Mulsanne, and then onto the circuit and up to the pits. That was the normal procedure.

Over 40 years, Singer was involved in 16 Le Mans victories

Motorsport Images

“But one year, with the 956s, we were a little late. When we got to the circuit entrance at Mulsanne Corner there was a young policeman who said, ‘No, you cannot pass’. He could see our cars were race cars, but he could only think of his orders. So we had to divert around local roads, getting stuck in the spectators’ traffic jams. When we finally got to the paddock the engineers said, ‘We have very high temperatures here. This is not what we want before a 24-hour race.’ After that we worked out of a big tent in the paddock.

“In 1979 Ickx stopped on the Mulsanne Straight during the night when a fuel injection pump belt came off. We always put a temporary spare in the car, to get the car back to the pits, but in the dark Jacky couldn’t see to put it on right and when he started the engine it flew off and disappeared. We sent a mechanic out to him with another belt, but when he got there he found he was on the wrong side of the track, so he threw the belt across the road. Jacky picked it up and fitted it, and got back to the pits; we did the job properly and sent him out again. But of course this had all been reported to race director Alain Bertaut. He summoned me: ‘We know you took a spare part out to your car.’ I said, ‘Sorry, I don’t speak French.’ He switched to English, and I pretended not to understand that either. So he found a German translator, and the game was up.” But Porsche still won Le Mans again that year, thanks to the Kremer 935 of Klaus Ludwig and the Whittington brothers.

By 1981 the 936 had been pensioned off, but it came out of the museum to be fitted with an adaptation of a 2.6-litre turbo flat-six that Porsche had produced for Indy racing with Danny Ongais’ Interscope campaign. It was the 50th anniversary of the foundation of Dr Ferdinand Porsche’s company, and his son Dr Ferry Porsche was at Le Mans that year, so the whole team was very relieved when Jacky and Derek had a perfect run to victory. It was the first of an unbroken run of seven Le Mans wins.

“The 956 for 1982 was something new: a monocoque. We hadn’t done one before. Mr Bott was always in favour of a spaceframe because it was lighter; torsional stiffness was of second order to him. But without a monocoque we wouldn’t have met the new safety regulations. We’d never done a monocoque before, so we had to learn it. And our first monocoque was actually just right, we never changed it through all the years of the 956/962. The longer-wheelbase 962 was built because of the IMSA regulations, which required the driver’s feet to be further back, but it worked well in Group C also.

Pink Pig 917 only raced once, but remains memorable

Motorsport Images

“Another development that emerged in racing but ultimately had major relevance for road cars was the dual-clutch PDK transmission. The gearbox guys first came up with the idea way back in the 917 days, but when we got a system built for a 962 we found it was half a second slower. The oil pumps were soaking up power. So we redesigned all that, and then it was 0.7sec a lap faster around Ricard. We usually only ran one car with PDK because we weren’t sure about its reliability: we won one race with it, Monza in 1986, and then we dropped it. Like the early ABS, so much of it was mechanical. Now it’s all electronic, and it’s in almost every 911.”

In 1985, during a championship race at Hockenheim, there was a furious fire in the Porsche pit during a refuelling stop. “It was a very hot day. The 956/962 had a filler on each side: one guy put in the petrol, another put an empty bottle on the other filler to take the air pressure that was forced out. The air bottle guy fumbled his coupling and the fuel fountained out all over the rig. I was standing in the middle, and the fire covered me. Porsche always had their own doctor at the track, and he got me into the helicopter and off to the burns unit at Ludwigshafen. I had 35 per cent burns.

“I was in hospital for nearly three months, and had a lot of skin grafts. While I was lying there I had two pieces of bad news. Within three weeks Manfred Winkelhock and then Stefan Bellof were killed, at Mosport and at Spa, driving customer Porsches. The following year, at Le Mans, Jo Gartner, driving a Kremer car, hit the barriers turning onto the Mulsanne Straight and died instantly. On the Friday Jo had come up to me and said, ‘My car is very loose at the rear.’ I said, ‘That’s easy, just raise the rear wing.’ He said, ‘The Kremer people won’t do that because of the extra drag. They want to do it with suspension settings.’ Maybe the car was still a bit unbalanced, I don’t know.”

Porsche 936 left the museum to grab 1981 win with Ickx/Bell

Motorsport Images

Porsche always worked closely with their favoured racing customers. “We had a separate department for that, run by Jürgen Barth, and teams like Kremer or Joest, rather than trying to develop their own equipment, could buy a front-runner for far less. It didn’t earn us much money, but it more or less covered its costs, and it got the Porsche name to the front of more races.

“We developed a real family relationship with some of our drivers, and we had a code for the pairings on the pit boards. Bell/Stuck were BEST, Mass/Ickx were MIX, and so on. BEST meant what it said: Derek was the ideal endurance driver, very fast, very reliable, and he thought like the member of a team. Unselfish: during the Group C fuel consumption era, if his co-driver had used too much fuel, he would without complaint drive to get it back onto the programme. In 1986/87 he created quite a mark by winning the 24-hour races at both Daytona and Le Mans, two years running. Hans too: a spectacular and exciting driver, but he always followed instructions to the letter.

“In 1987 Jaguar won the Sports-Prototype Championship, but we still won Le Mans. We would have won it in 1988, too, but we lost it to Jaguar because Klaus Ludwig, sharing the BEST car, made a mistake. When the fuel light came on you knew you had one full lap left in the tank. He tried to do two laps, and ran out in the Porsche Curves. He managed to get back to the pits on the starter motor, but that lost us two laps. Hans and Derek made up a lot of the time, and at the flag we’d lost the race by 2min 36sec.”

There are many more threads to Norbert’s Porsche career – like the Indycar project. “The space engineer Wernher von Braun told me, ‘From a success you don’t learn. But with every failure you have, you learn a lot.’ He’s right. If you make a car, and go out and race it, and win, what have you learned? In 1986 a Porsche Indycar programme was agreed. We built a 2.65-litre V8 engine and our own chassis, but after Al Unser Sr had done just one race Al Holbert, who was in charge of the American side of the programme, insisted we switch to a March chassis. We’d barely got the Porsche chassis shaken down, and later, in a back-to-back test with Teo Fabi at Firebird Raceway, we ended up with better times from the Porsche than the March. But by then the decision had been taken.” Al Holbert died in an air crash in September 1988.

Fabi won a race at Mid-Ohio the following September, still using the March chassis, but in 1990 the programme was wound up.

Ferocious 917/30 toppled McLaren for Can-Am glory in 1973

Motorsport Images

With Formula 1 engines there was success and failure. The TAG Porsche turbo V6 unit brought McLaren five world championship titles in three years, 1984-85-86. “John Barnard was involved from the start to ensure that car and engine were designed together.” Then there was the abortive Arrows V12: “Too heavy, and the Arrows wasn’t very good either, so Arrows blamed the engine and Porsche blamed the chassis.”

In September 1988 came a bombshell. The Porsche board dictated a complete withdrawal from racing as a works team. “They said, OK, Norbert, no more racing. The competitions department was closed down, and I was moved to production car suspension development. It was like cutting off my legs. Two days later I had a call from Jean Todt, who was putting together the Peugeot endurance team, and wanted me to run it. I went to see him and got into it pretty deeply. We talked terms, I found a German school in Paris for my kids, but in the end I decided the language difference would make it very difficult. And though I had lost my racing role I was still, deep down, a Porsche man.

“In my spare time I started helping Reinhold Joest, who was running a 962: through 1989 and ’90 I did some new wings for him and other details. I fitted it in somehow. Road car development was usually timeless, get it done for next month, maybe the month after. Racing work was always urgent.

“Then, when the new GT rules came in, Porsche decided it was appropriate to return, and we managed to homologate the Dauer road-prepared 962 as a GT car. At Le Mans we were going for the class win, but we got an unexpected overall victory. Then McLaren won with their F1 GTR in 1995, and a month later we got the go-ahead to start developing the GT1 to beat them. We took a 911, cut it in half, and turned the back around to put the engine ahead of the rear wheels.

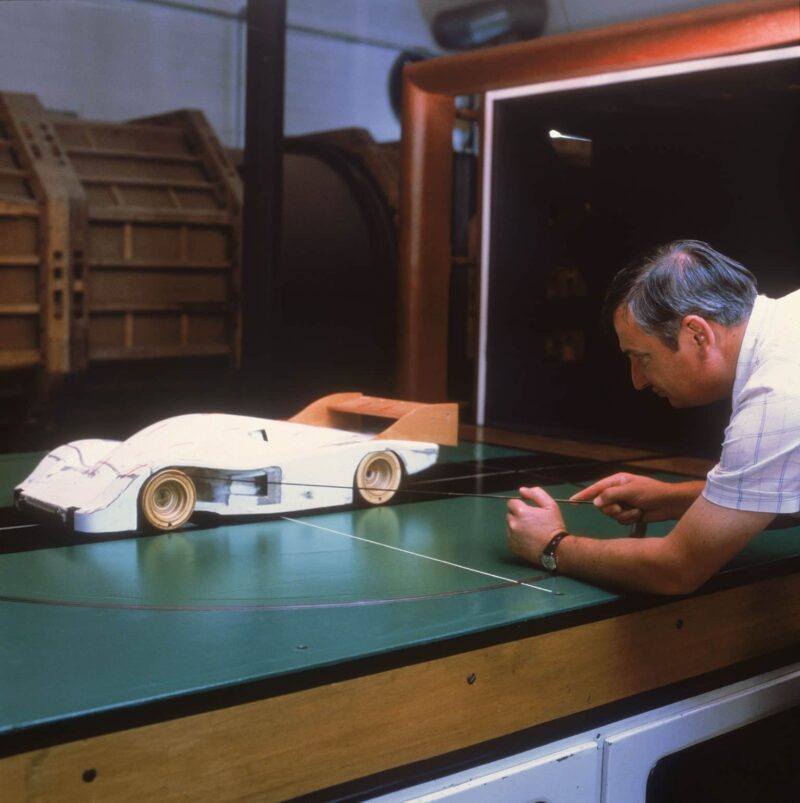

Singer tests early 956 tails in the wind tunnel. He says he became an aerodynamicist “by accident”

Motorsport Images

“In 1996 our GT1s were second and third at Le Mans, winning the class and pushing the McLarens out of the top three. The actual winners were Joest in a car we’d originally engined for TWR for IMSA, based on a chassis Ross Brawn had done for Jaguar. But with our engine and gearbox, we were still happy to take it as another Porsche Le Mans victory. Our works GT1s were leading overall in 1997, but a broken driveshaft caused a crash that put one car out on Sunday morning, and late in the race a broken oil line set the other one on fire.” But the Joest car won again, so that counted as the 15th victory.

Something more was needed for 1998, and Weissach came up with the carbon-chassis GT1-98. This time it all went right: two cars started, two cars finished, first and second. It was Porsche’s 16th Le Mans victory in 29 starts. “And it was a particularly important one, because it was the 50th anniversary of Porsche producing their first car. Dr Ferry Porsche had died earlier that year, but his son Wolfgang Porsche was there, watching in the pits. They wanted me up on the podium with the drivers, but I refused: I said that Dr Wolfgang must go up. Porsche is not just a faceless company, it is still like a family, and that was a family moment.

“At Porsche we’ve never had one star name on the design team, or one star team manager. Sometimes in F1 you get a personality designer in a very good team: they’re all doing their best but he gets the honour. Or if he really is responsible for much of a team’s success, when he moves to another team maybe the success goes with him, almost as if the team cannot manage without him. At Porsche if we are building a car, and one of the mechanics says, ‘Would it be a good idea to do it like this?’ we will always listen, even if in the end there are reasons why his idea would not work. Everyone is a key team member, and their ideas must be heard like everyone else’s. It’s not, ‘Shut up and do as you’re told.’

“My work contract with Porsche ended in 2004, but I continued as a consultant, and worked with the customers. One race I remember particularly was the Spa 24 Hours in 2003, won by the Freisinger GT2 Porsche of Marc Lieb, Stéphane Ortelli and Romain Dumas. It was a tricky race weather-wise, like it often is at Spa, rain, dry, rain, dry. In those races you always seem to end up on the wrong tyres. But that day all my decisions seemed to be the right ones. Dumas was the team junior, and when Lieb brought the car in on slicks it was actually raining. I told them to put on a new set of slicks, and Dumas looked at me with his eyes big and round. But I said, ‘Just take it easy for a couple of laps, you’ll be fine.’ So off he went on shiny new slicks. After two or three laps a dry line appeared, and he piled on the laps while the others were in the pits trying to decide which tyres to use. I realised then that Romain is one of the good guys. He’s in the Porsche LMP1 team now, of course.

“I finished with Porsche completely in 2010, after 40 years. Then the ACO offer came up, so my relationship with Le Mans continues. I analyse the respective performances of all the cars, particularly in the GT classes, lap speeds, section speeds, top speeds. I pass on all this information with my comments, and what they do with it is up to them.”

Norbert remains fascinated by the whole scene. Audi’s Le Mans score is now 13 wins, and Porsche is keen to hold the gap. “Audi is still very strong, not so much in speed as in consistency. Today, if you have almost any sort of problem, you have lost Le Mans. Electronics have changed a lot of things, and today’s cars are much more reliable. With three drivers doing short stints, you can go flat out all the time.”

I ask Norbert who now does his old job in the Porsche Le Mans team. “I think it’s a lot of people. In my day it was a small team, we all knew what was going on. A lot of the important decisions were taken on the staircase, in the canteen, walking briskly through the passages. If you needed some shop-floor information you’d talk to a mechanic. Today if there’s a problem they have a meeting about it, someone takes the question away and comes back a week later. There is a lot of Formula 1 thinking, and I am not sure the new personnel remember all those 16 victories. Marketing decides racing policy nowadays, and the racing department is like an offshoot of the marketing department. The board decides on the effectiveness of a race programme compared to the cost of a television campaign, or some posters beside the road.

“But, to be fair, it’s really the challenge of hybrid technology that has brought Porsche back. And, developing your road cars, even today you can’t rely totally on simulations behind closed doors. You still have to see what happens out there, on the track. Even today, racing can still improve the breed.”