Team tenacity: Why Mercedes is the works

The backstory behind the three-pointed star’s dominance in Formula 1 is a fascinating one – and will make uncomfortable reading for its rivals at Red Bull, Ferrari and McLaren

Mercedes

For Mercedes there was a nice historical thread to its early dominance of F1 this year. It conformed to a pattern of years ending in ‘4’ (1914, 1934, 1954), seeing its technical superiority in Grands Prix wipe the floor with the best the world could throw at it. But for Merc’s chief rivals, such numerical niceties meant nothing. All the Merc dominance symbolised to them was a painful truth: they had failed.

The smaller teams had no need to be too hard on themselves, given the vast differences in their resources to those of the top teams, resources that allow a major team to investigate multiple early options in the conception of new cars around a totally new formula and then simply select the one that looks best. But Ferrari, McLaren, Red Bull? What were their excuses? The aftermath of the battle scene elicited some angry flailing from Red Bull and Ferrari about how it could have come to this, which essentially could be condensed to a single view: the formula is ‘wrong’. But lashing out at the new formula was only covering competitive pain and embarrassment and their real question – the one that has spurred competition onward through time – was, “How the hell have they done that?”

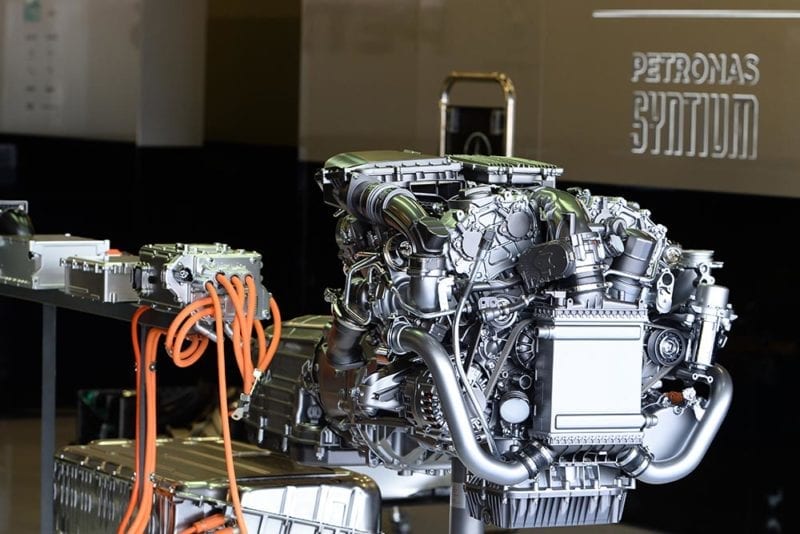

In terms of the hardware – the Mercedes W05 – it was simple enough: as you could read in last month’s magazine, it’s a car that’s been conceived around a piece of highly original thinking in the layout of the turbo’s compressor, something that has brought compounding advantages to the car in this compounding formula. But how did the team get there? Why them and not anyone else?

It’s a five-year story of opportunity, engineering brilliance, sheer grit and tenacity. The most significant parts of the story unfolded in Brixworth, the rural Northamptonshire site of Mercedes High Performance Powertrains where Andy Cowell rules with an affable but steely commitment to the cause. Forty-five years old, he’s ex-Cosworth and joined what was then Ilmor (now Mercedes HPP) in 2004, was chief engineer by 2006, a director by 2008 and has been MD since 2012. He’s one of those rare people who can communicate the complexities of their subject in terms readily understandable to an interested layman – the mark of someone who truly knows their stuff.

There’s no stiff formality or projecting of a status, just down-to-earth enthusiasm and bubbling energy; no-nonsense, approachable and polite – but deeply competitive and totally immersed in his world. His flair as a communicator and the obvious sincerity and soundness of his beliefs make it easy to imagine how he has inspired a collection of hundreds of talented engineers to operate as a single, on-target unit, with a shared vision and an unprecedented degree of openness between chassis and engine people that has minimised ‘losses in the system’. He runs any project just as he would one of mechanical design, keeping a wary eye out for losses, routes that the energy might travel unproductively if not guided in the right way. It’s particularly apt within a story of the hybrid energy formula. But Cowell and his team were doing all these things already, even before the new formula. Payback has been amplified by a series of circumstances that played perfectly to these strengths.

Mercedes leads the way in Australia, somewhat setting the tone for the 2014 season so far

Motorsport Images

Understand first of all that the idea of separating the turbo’s compressor from the turbine – the feature at the very heart of the W05’s current supremacy – was suggested by the Brackley chassis group back in 2011. When Brixworth confirmed that it was indeed feasible, the design group followed up with a further request about the Spitfire-like straight exhaust arrangement – made possible by the relocation of the compressor – that costs some power but evidently brings a net gain when the aero-enhancing packaging possibilities are fed into the equation. Brixworth, in other words, was the facilitator of a total car design that has brought real advantages – as well as honing the power unit that has significantly more horsepower than those of Renault and Ferrari. The advantages of being an integrated chassis and engine manufacturer have been massively enhanced by the transition from the frozen-spec V8 era into the new hybrid V6 formula. But the Brackley-Brixworth axis has worked that advantage better than any other.

Theoretically, Ferrari is the most integrated of all, with engine, chassis and aero departments all on one site. There is a half-hour drive between the Mercedes chassis/aero group in Brackley and the engine group in Brixworth – and those two parties have been together under one umbrella only since 2010. There’s a cross-channel flight – and a whole culture gap – between Red Bull in Milton Keynes and Renault Sport in Viry.

“Ideas came flooding in from all over the place”

So structurally Mercedes is not as integrated as Ferrari. But get Cowell onto the subject of how the relationship between Brixworth and Brackley has developed and you begin to see the strength of integration is not just about where the buildings are. “It goes back all the way to December 2008,” he says, “when there was the initial discussion about Mercedes powering what became Brawn in 2009. That’s when the relationship started – a small group of people here were involved with Ross and the engineering team through 2009. But 95 per cent of the organisation was working with McLaren and had done for the previous 15 years.

“Then for 2010-11-12 [as the former Brawn team at Brackley became the Mercedes works team, and McLaren became merely a customer] we were building the relationship at a deeper and broader level. We had to understand what Brackley had the capacity to do as we built that relationship, because there was a reduction in numbers [compared with McLaren and as the Resource Restriction Agreement took effect].

Brixworth chief Andy Cowell talks power to Nico Rosberg

Motorsport Images

“We increased the number of meetings and broadened the relationships. A customer relationship is ‘here’s the product, here’s the phase document, here are the connection points, that’s it. If you’d like us to do some development work, we’ll quote you on it, you’d need to cover all our costs’. A works relationship is our materials science group providing support and building relationships with the real scientists that are now present at Brackley. It’s the concept, the very first line that goes down on the CAD screen here marrying up with the very first line that goes down on the CAD screen in Brackley for the chassis. Going all the way up that R&D food chain, building the relationships there and recognising the sensitivities for what would make a fast race car. It’s not one part that makes a race car fast, it’s the amalgamation of all those systems; it’s a balanced overview.”

That’s the process – and it was helped enormously by the similarly enlightened and straightforward attitudes of Ross Brawn, Bob Bell, Geoff Willis and Aldo Costa, then the respective team boss, technical director, technology director and engineering director at Brackley. But what came out of that process were the crucial questions that led ultimately to the speed of the W05. “Ideas came from all over the place,” says Cowell. “From guys that were building the development engines, guys that were building the cars, guys designing the aero, guys designing plenums… Ideas flooding in.”

What should not be under-estimated in this process is how the performance of the Brackley team itself had been boosted as the changes made under Ross Brawn’s leadership – the recruitment of Bell, Costa and Willis, the re-arranging of the aero department, the installation of a 60 per cent wind tunnel – came to have an effect. Paddy Lowe, who joined the Brackley team as engineering director last June after 15 years at McLaren, was perfectly placed to see the level of the team. “It’s clear the engine is great; it has more power than the other two engines and in this formula that compounds. That immediately puts us in a different place from teams running other engines. But then there’s the team performance and, if you look at where we were last year, you’ll see there’s been huge progress made over the last couple of years on tyres and aero and other systems – just a better understanding. As a chassis team we’ve positioned ourselves as being among the top two or three, as we saw last year.”

Well integrated organisation leads to supremely well integrated – and currently – dominant – power unit

Motorsport Images

Paddy was also ideally placed to see close-up the difference between customer and works status. “As it became a joint project between Brackley and Brixworth, it was quite clear that the customers would get what they got – not to say it wouldn’t work for them, but they were not involved in shaping the architecture of the engine. They would simply get to look at what came out and then decide how to exploit it. Once McLaren was no longer the works team, the relationship changed. If I go back to 2006-08, that period of success for McLaren as the works Merc team, that was technically a very close working relationship. Through 2009 that was in effect stopped and moved to here. I see there is an even stronger collaboration here than I saw in the McLaren works days. The W05 was inextricably related to what was being done at Brixworth. That was immediately obvious. At the other extreme, McLaren wasn’t a works team and, with Honda coming [as McLaren’s new engine partner from 2015], Mercedes wouldn’t want to be giving them info.”

McLaren, just like Force India and Williams, first got to see full details of the new engine and its unique compressor and exhaust layouts when they signed their contracts in the spring of last year. This was well past the time of first principle decisions on long-lead items such as monocoque and gearbox dimensions. They therefore had no hope of being able to incorporate those features as fully into their designs as the team that requested them in the first place – way back in 2011.

“We’re all working for one company now, to make a fast ‘Silver Arrows’ car”

But there has been a benefit even beyond that of just works team status. Even when McLaren was Mercedes’ official F1 partner, even as Mercedes owned 40 per cent of the team, it was still very much McLaren. There was a very clear distinction between the two entities and inevitably this could be felt during any discussions and meetings – even for projects that were for the joint benefit of both. “We’re all working for the same company now,” says Cowell, “and all have the objective of making a fast ‘silver arrows’ car. Ultimately we all work for [Mercedes chairman] Dieter Zetsche in Stuttgart. That has an effect. If you’re all in the same family then every head of a system can say what is good for that system, but if they can explain in complete detail why it’s good for that system without fear of giving it to an organisation that… without fear of IP leak, it’s so much easier.

When you’re sat around a table trying to work out where the balances are and where you should do something a little bit different with the turbocharger, if you can have a completely open conversation about what would be good to do and why – why as in depth – It just makes all those decisions easy and the downstream effort less stressful. You don’t have that feeling of, ‘They’ve said what they’d like but they don’t really say why, so I’m busting my nuts, but for what real purpose? So I’m just going to have to trust him or he’s at a higher pay scale therefore I’ll just have to accept it’. All that disappears within one organisation. There is no guardedness about what anyone’s doing and that just relaxes the situation. With McLaren those discussions were ‘majority McLaren, minority Mercedes’.”

Mercedes power to the fore on the Bahrain GP grid, before a 1-2 for Lewis Hamilton and team-mate Nico Rosberg

Motorsport Images

As head of McLaren Ron Dennis always raged against the idea of his team being swallowed up by a manufacturer. Brackley – a team rescued on limited resources from the ashes of the Honda pull-out at the end of 2008 – had rather fewer options. The resultant single vision has been to the benefit of the performance of both Brackley and Brixworth and has made for a total greater than the sum of the parts. A more extreme version of McLaren’s independence from its official engine partner is Red Bull’s relationship with Renault Sport, which at times seems positively adversarial. It’s a partnership in the business sense of engines supplied cost-free, but in the technical collaboration sense hardly at all. Their supplier/client relationship worked fine in the frozen-spec era but has been found wanting as F1 has headed into a technical period requiring a complete re-evaluation from first principles.

For the customer teams – McLaren now among them – this co-operative process simply couldn’t happen. But at Ferrari there was a similar process and it’s interesting that the F14T and W05 share some key design features, notably the dolphin nose, water-air intercooler and separated turbine and compressor (though Ferrari stopped short of siting the compressor at the front of the engine, wary of the long connecting shaft running the length of the engine turning at 150,000rpm, and its associated bearings). But it’s also clear now that the Ferrari engine department’s expertise in hybrid technology was less than that of Mercedes HPP.

So essentially into this new formula we had only two genuine works teams – Mercedes and Ferrari – when the advantages of being so were immense. And of those two works teams one – Mercedes – had a much more complete understanding of hybrid technology within the company. Why was that so?

Mercedes bought into hybrid technology more fully than either Renault Sport or Ferrari. It was already doing so even as the regulations were in their formative stages. Mercedes the road car company even assigned Brixworth a leading role in the development of electrical power. What started out as a lunchtime paper design at Brixworth became the Mercedes SLS AMG Electric-Drive, an all-electric sports car developed in some newly erected Portakabins on site.

The first-generation hybrid regulations (KERS, introduced to F1 in 2009) were formed three years earlier and it was at this point that the then MD of Mercedes HPP, Ola Kallenius, realised that there was a potentially valuable overlap in where Mercedes the main company and Mercedes HPP needed to invest. “It was decided [at board level] that Brixworth would lead the charge on KERS development,” Cowell says, “and at that stage – 2006 – there was zero knowledge either here or in McLaren on how to do that sort of system. So initially we used consultants, companies from outside with more knowledge of the technology. But for that 2009 system we ended up doing more of it than we anticipated, especially with the battery.”

Engineering director Paddy Lowe came to Merc from McLaren

Motorsport Images

The ‘hygiene’ factors of racing car engineering – minimising weight and volume, keeping it as simple as possible, quick turnarounds – and the aggression with which those aims are pursued can be a culture shock to companies outside racing. As HPP hit those barriers, it took the decision to invest, to recruit the technology expertise into the company and develop it from there. Cowell says, “To get the performance and reliability needed – especially in terms of integration into a race car – we realised we had to have the expertise in one department with one man overseeing it, otherwise it’s not going to be as efficient to manage, and what you get for the money you spend won’t be as great. If you’re trying to manage lots of different companies it’s a huge drain. Every company has a slightly different culture.” Minimising losses in the system, in other words. “We recruited a guy in late 2007 specifically for KERS. He’d seen that journey. And he pulled it all together.”

The in-house expertise grew and developed – and was reflected in the second-generation KERS of 2011 which was much more of an in-house project. “That was a much more integrated package,” Cowell says, “and came about not just through our greater knowledge, but from the input of both McLaren and the Brackley team. This was 2010, so around the time of the changeover from Woking to Brackley. Because both teams were going to be using it we had joint meetings, all three parties in one room, to decide upon what was the right aspect ratio for the KERS module, where the connection points should be, where’s it best to put the circuits, for a generic fast race car. McLaren in those meetings was more experienced in KERS because it had raced it in 2009. The Brawn didn’t have KERS, but they were great meetings. Any sense of ‘we’re opponents’ was left at reception and we just sat down and worked out the best way – and that has paid off. It’s helped the engineers here who are working on the parts that go inside the ERS module to have the comments from those meetings still ringing in their ears.

“Our current circuit architecture, for some of the DC/DC converters for some of the gate drives and so on, is of an identical ethos to the 2011-13 KERS, just rescaled. If we have a problem with our ERS system we have a chief engineer who understands how it all works; we don’t have to call four companies to get them in to ask, ‘Why’s this not working?’ We don’t need a group of system integration engineers – it’s done at the concept stage, the first layout.”

Mercedes power unit has been the engine of choice so far in 2014

Motorsport Images

Concurrently Mercedes HPP had been helping frame the new hybrid formula. Renault and Ferrari – and others not yet in F1 – were involved in that process too, but it’s probably fair to say that Mercedes knew what its own relative strengths were as it helped form the new formula. “Back in 2010 before an FIA regulation meeting,” Cowell says, “Ross Brawn, Bob Bell and myself would have a briefing, then another briefing after the meeting to think about what’s the right thing for the sport, and what would be good for us as well.”

The timing of Mercedes’ withdrawal from McLaren at the end of 2009, to purchase Brawn, was quite serendipitous in that it coincided with the early stages of planning for an all-new formula. Projects were being started from scratch, minimising the growing pains of a new relationship. A lot of the accumulated knowledge benefits of the McLaren-Brixworth partnership were about to be rendered obsolete. This too has been a crucial part of the Brackley team’s current success in terms of its own performance and in neutralising the advantages of McLaren, a key rival.

Furthermore, the tightly knit partnership of Cowell, Brawn and their respective lieutenants facilitated a development path that has proved both more rigorous and faster than those of rival programmes.

“It’s about determination and tenacity because all of racing is R&D and the success rate is low”

“When the current regs came out [in June 2011] we were determined to get a performance platform together as soon as possible,” Cowell says, “so we could start developing things that would never go in a race car but were dyno-friendly. The mass didn’t matter. All the dynamic parts – valves, pistons, rods, crank – needed race intent, but that wasn’t so with crankcase and cylinder head. The cooling needed to be race-intent, the architecture too. But we didn’t start lightening it on the outside, and made sure we could do all the development tests we wanted very quickly. It was development-friendly in terms of being able to do quick port changes, quick cam changes etc. We got that together in an impressive time frame, which allows you to start understanding the performance potential of all the systems and therefore their performance authority in a race car. You can then sit down with the people who are pulling together the whole racing car, as one group. Then it’s a case of balancing it, based on performance authority and the overall fastest race car. There are some unusual features that have good performance authority and you start trying to work on them. But the key thing here is that you have to make decisions: are we doing it or not? If you stay in that no-man’s land, it’s just inefficient. Ross is a no-nonsense sort of person, Bob was up for making those decisions, we’re up for making them and therefore it was easy to say, ‘OK, that’s the overall concept, get on with it’.

Mercedes team celebrate at Russian GP, Sochi

Motorsport Images

“Engineering is a balance – creativity, gut feeling, the best simulation in the available time, understanding that it’s doing a thorough experiment that gives you the answer. If you’re concerned about reliability you have to run it in a harsh environment and see that the bits are still OK. If it’s a performance idea the torque meter on the dyno or the wind tunnel will give you the answer. It’s also about having the bloody determination and tenacity because the whole of racing is R&D and the success rate is low. A 20 per cent success rate in R&D is good. Therefore it’s having the tenacity to hang on to the potential gain when it goes wrong a few times, to pick yourself up, dust yourself down, and say, ‘All right, what have we learned, what we going to do now?’ and not give up.”

There are many gifted and hard-working engineers at both Ferrari and Renault Sport, just as there are in Brixworth. The difference comes in how they have been utilised, managed and inspired. That and a clear-thinking commitment on the part of Mercedes HPP to invest in the future: just what proportion of its income did Red Bull invest at the time? Without the balance sheets of each of the three engine programmes, it’s impossible to assess how that commitment compared. As Lowe says: “Some of it we shouldn’t pretend to understand. We just do the best job we can and other people do their best and you end up with a set of lap times. But the great thing about this formula is that an engine advantage compounds. If you can make more power from your permitted fuel flow, you’re more efficient. You can run less fuel or recover more of the lost energy or a combination of both – and it makes you faster still. I think that’s a big part of our current advantage.”

They have established themselves as a winning entity worthy of the Mercedes star. Best not get them started on how much potential they reckon Stuttgart’s resources might harness…