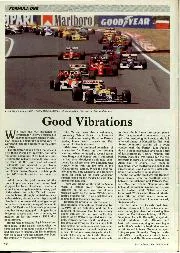

“I knew the car was good. The Hungaroring was the only place where the car was performing well so I got a clear lap in qualifying and put it on pole. When I say the car was good, I mean it was good up to a certain level. Not as fast in race conditions as the others – but I could drive it in such a way that the tyre wear was not as high as the other cars – so my tactic was to stay out the whole race, no pitstops for tyres at all. And it worked. But at the end I was right on the limit, there was just no rubber left on the inside of the rear tyres, none at all.

“For me, this was a big achievement because it was not easy at all, and I made no mistakes under big pressure. You have to understand Ayrton Senna was my best friend in F1, in my life actually, but we were fighting each other that day, both of us 100 per cent, so I was pretty happy at the end. He could have tried to push me off but he didn’t do that… I wouldn’t have minded if he had tried,” he holds up his hands and laughs, “but there was no room to pass and I was never going to give him any room. Absolutely no way. He was my friend, yes, but I had the race under control.

“We first met in Detroit in 1984 when we raced each other in uncompetitive cars, he in the Toleman and me in the Arrows, but we had a good battle. Later we became very close friends. He was the strongest man I ever met, I admired the way he dealt with life and with racing. He was different to anyone else: nobody could match his commitment, nobody. And he had the skills to drive the car at the limit more often, and for longer, than anyone else.”

Boutsen held off Senna to win in Hungary ’90

Simon Bruty/Allsport via Getty Images

We are nearly at journey’s end. He checks his watch, checks his phone, tidies his immaculate haircut (the same as it ever was), flicks dust off sharply-pressed black trousers, and slips on the company jacket. Just time to ask him about the end of his career and that horrendous crash at Le Mans in 1999 when a backmarker strayed into the path of his Toyota GT-One and left him with serious back and leg injuries.

“It was going to be my last race anyway, I’d already decided to stop,” he tells me, “but this was a more brutal stop than I was expecting, not the nice soft one I had planned. I was very lucky to escape from that crash. It took me a long, long time to recover, to be able to live a normal life again. It was two years learning to walk normally and four years to be able to sleep without any pain. The crash was absolutely nothing to do with me, but that is motor racing; anything can happen when you are out on a racetrack. In most accidents, you are the victim of something beyond your control, but I was lucky to be in good hands afterwards and my wife Daniela supported me very strongly, every minute of the time, every step of the way back.

“It was a nasty crash, yes, and bad luck, but I was also lucky – to survive and to recover.”

Earlier he mentioned musical chairs – five teams in 10 years. Maybe that had held back his career in some way. Or not?

“I enjoyed every minute of it. Not many drivers can say that”

“Some choices I made, others were made for me,” he explains patiently. “I decided to move from Benetton to Williams in ’89 and that was a good decision. Williams had huge experience, huge potential, and Flavio [Briatore] was not yet at Benetton to bring all the good things together. The cars were competitive, nice to drive, and with Riccardo [Patrese] we had a really good atmosphere in the team. I’m not saying I liked him – I mean, he was my biggest competitor and I had to beat him, you had to hate your team-mate, you know,” he laughs. “Frank [Williams] made it clear that the drivers’ championship was not important to him, he wanted the constructors’ titles, and that can de-stabilise the drivers a little bit. He was never really behind his drivers because who won the race was less important to him than his car winning the race. You could feel that.

“But it was not my choice to leave; this was made for me, because the team could make more money with Nigel [Mansell] than with me. It is not only a sport, it is a business, and a business to make money. A driver can lose his self-belief so it is really important, all the time, to be fit, physically and mentally, because once you sit in the car you are alone. You must cope with many things, technical things, all the paddock gossip, and mental challenges, so you must be fit to stay at the top.”