Lunch with .... Tony Southgate

He’s one of the most successful designers of all, with Grand Prix, Indy 500 and multiple Le Mans winners to his credit. And when he retired, he went racing…

James Mitchell

It’s progressively harder these days for racing car designers to demonstrate true versatility. Formula 1 has greedily made itself the centre of everything, yet the very strictures of its regulations seem to stifle original thinking. As the permissible solutions to each problem become ever more confined, so today’s F1 cars become ever more identical – witness this year’s unlovely stepped noses. If you painted a Ferrari and a Williams plain grey, could anyone but an expert tell the difference?

But in considering the career of Tony Southgate, versatility is the irst word that springs to mind. He is surely the only single designer to have created cars that have won the Monaco Grand Prix, the Indianapolis 500 and the Le Mans 24 Hours: and then gone through the complete change of mind-set needed to design a championship-winning four wheel-drive rally car. In 40 years he worked for some 20 different teams, from Germany to Japan, from Lincolnshire to California. And always he relished any challenge that required, metaphorically as well as actually, a clean sheet of paper.

We eat in the excellent Albero restaurant attached to Northampton College, close to Tony’s home: he chooses manchego cheese tortilla, crisp sea bream on spinach and a glass of chardonnay. He was born in Coventry in 1940, when the British motor industry’s home town was being regularly bombed by the Luftwaffe. His boyhood passions were art and engineering, and when he left Technical College at 16 his ambition was to land a Jaguar apprenticeship. He failed – which, 30 years later, made the Le Mans victories by the cars he’d created for Jaguar all the sweeter. Instead, while serving a five-year engineering design apprenticeship in a non-automotive company, he nurtured his motor-racing ambitions by joining the 750 Motor Club and building an Austin 7 Special. Very small and low for its day, it was raced three times before a broken crank and no money to mend it spelt the end of his racing career. Undaunted, he vowed to find a job designing racing cars. Colin Chapman was his hero, so he wrote to Lotus. A brief reply told him there were no vacancies. He was to be head-hunted by Chapman 20 years later…

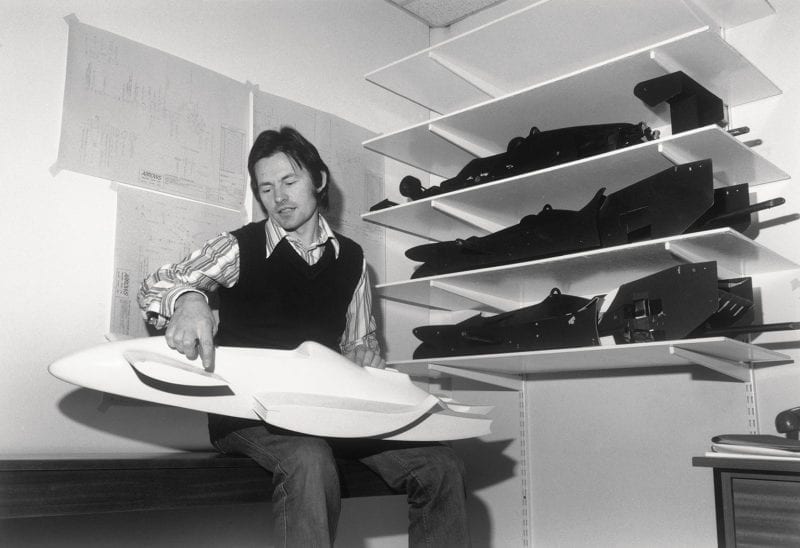

Pivotal Lola Mk6 was an early project

Motorsport Images

Tony admired the Mk1 Lola- Climax – “proper twin-link suspension, offset engine, and it won everything” – so he wrote to Lola. Back came a letter from Eric Broadley himself, summoning him for an interview. “I arrived at this tiny building behind a little garage in Bromley, armed with drawings of an 1172 Formula car I’d dreamed up: transverse engine behind the cockpit, driving a Mini gearbox by chain.

Eric asked me how I’d arrived at the suspension geometry. I hadn’t a clue about geometry then, so I flannelled – I told him I had to work within the dictates of the fixed-length Mini drive-shafts. That seemed to satisfy him, so he offered me a job at £13 a week. I found some dodgy lodgings nearby and, at 20 years old, I was in heaven.

“At that time Lola consisted of six people. Eric would sketch out the concept and work out all the geometry of each new design, and I’d draw it up and ill in the gaps. Then I’d make the jigs, and start fabricating the parts of the car itself. After the Mk3 Formula Junior and the F1 Mk4 for Surtees and Salvadori we set about the Mk6, Eric’s trend-setting vision of a V8 mid-engined GT. It took six months to design and draw. John Frayling, working freelance, did the shape in a quarter-scale model and it looked fabulous, although it never went near a wind-tunnel.

1972 Monaco win was final flourish for both Beltoise and and BRM

Motorsport Images

“So we enter the irst car for the Le Mans 24 Hours. After several all-nighters we’re running really late, and we inish it just in time for Eric to catch the ferry. We’ve painted on trade plates back and front. Eric climbs into the driver’s seat, race mechanic Don Beresford gets into the passenger seat with his tool-box on his knees, bloody great unsilenced V8 starts up, Eric tries to drive out of the workshop, and there isn’t enough steering lock to get through the door. I get a saw and chop away at the front arches with Eric saying, ‘Hurry up, Hurry up’ and then he’s gone, blasting off down the A2 to Dover. On the way the throttle jams open, so he gets to the ferry driving on the ignition switch, and as they cross the channel Don works away in the hold rigging up a repair. Down the French roads among the camions to Le Mans, and after a few scrutineering dramas David Hobbs and Richard Attwood run really well in the race – until the cable linkage to the Colotti gearbox gets a bit loose. On Sunday morning Hobbo arrives at the Esses in neutral and thumps it, and that’s that.

“The car really impressed Ford, and all these heavies in shiny suits arrived from Detroit, poked around in our little workshop in Bromley and took the project over, moved it to a big new factory in Slough to become the GT40. That didn’t look good for me: I’d done all the work with Eric and now, as the young lad among all these big-timers, I’d be lucky if I ended up making the tea. So I jumped ship to Brabham. Ron Tauranac was the best production race engineer there was. Very practical, knew what the customer wanted, but not easy to work for. He didn’t draw, but he’d look over my shoulder and say, ‘Nah, don’t like that.’ After 10 months Eric Broadley called. A year into his two-year contract with Ford he’d had enough, he wanted his independence back. So I went back to him.

“At Lola I started in on the T70, the big Can- Am car, and we did the Mk3 coupé version too. John Frayling did the styling again. The T60 F2/F3 car was Lola’s irst monocoque single-seater, made of folded steel sheet spot-welded together, and the T80 and T90 were Indycars. Graham Hill won the 1966 Indy 500 in a T90. The T100 was F2 again, sometimes using the very tall Apfelbeck BMW engine, and I did a one-off sports-racer for BMW, the T120. When Formula A started in the States I had the idea of using up our stock of T70 suspension parts to make a simple, affordable tube-frame single-seater, the T140. It sold well in America, and over here in the early days of Formula 5000.

“John Surtees was effectively the works Lola driver, very demanding, but everybody respected him. When he started his relationship with Honda he needed an F1 chassis double-quick. In six weeks we did the T130, which Honda called the RA300: effectively the Indycar with symmetrical suspension, smaller tank, different brakes, and that massive great lump of a V12 hung on the back. First time out it won the Italian Grand Prix, and everybody was gobsmacked. It was a bit lucky, because Hill’s Lotus 49 blew up and Clark had fuel starvation, but a win is a win.

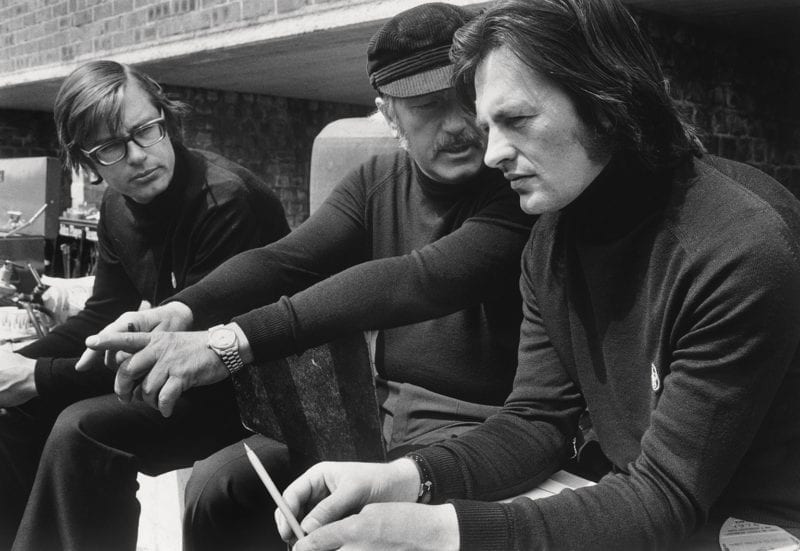

Tony with John Watson at TWR

Motorsport Images

“Lola was like a family to me, but I knew I’d always be No 2 to Eric in design terms, and I wanted to do my own thing. Pete Wilkins, a brilliant Australian fabricator I’d known at Brabham, was now in California working for Dan Gurney, and when Dan wanted a designer for his new F1 Eagle Pete mentioned me. I assumed the job was in Eagle’s F1 base in Sussex, next to Weslake’s where the V12 engines were built. Within minutes of accepting I realised it was at Gurney’s HQ in Santa Ana. I went over on a visitor’s visa, started work, came back to the UK to get married, and it took three months to get a visa for Sue before she could join me.

“I started work on quite a radical F1 car, small, with a lat nose to gain downforce and a very low centre of gravity. Then – whether for funding reasons or because Dan had a change of heart I never quite knew – the F1 programme got cancelled, so we concentrated on the Indycar. This shared some features with the still-born F1, with a Coke bottle-shaped monocoque. The Indianapolis 500 was a huge event: I stood on the grid looking up at that great cliff of people in the stands and thought, this really is a big deal. And we won it. Into the inal laps the Eagles were 1-2-3: Bobby Unser with a turbocharged Offy engine leading, Dan second with the pushrod Ford V8 with three-valve Gurney heads, Denny Hulme third using the four-cam Ford V8. Then Denny got a puncture and slipped to fourth, but it was still a huge victory for us. The Formula A version won the SCCA title in ’68 and ’69, too. The ’69 Indycar wasn’t such a big step forward, but Dan still came second in that year’s 500.

“I loved my two years in California. I’d been getting £37 a week at Lola; at Eagle I got £75 a week, and everything was cheaper than in Slough. We saved money, I bought myself a new Pontiac Firebird, and we’d go to the mountains at the weekend. But Sue found it all very brash and she missed England dreadfully, so when an offer came through to join BRM as head of chassis design I said yes, straight away. I wanted to be in F1. So we swapped Santa Ana, California for Bourne, Lincolnshire, and Sue was delighted.

“BRM was something else: as many characters as a stage play. Big Lou, Louis Stanley, reckoned he was the boss because he was married to Jean Owen, sister of industrialist Sir Alfred Owen who owned the team. Stanley liked to think of himself as England’s Enzo Ferrari. He was fine as long as everything was going his way and making him look good. But what I liked about BRM was that everything was made in-house: car, engine, gearbox, the lot. There were about 20 people in the drawing office. Aubrey Woods – everybody called him Strawberry – was the engine man. Alec Stokes, who did the gearboxes, was called Budgie because his hobby was breeding budgerigars. He’d been there since 1948. Raymond Mays was still around, just being Raymond Mays. Tim Parnell was the team manager, with down-to-earth common sense and a great sense of humour.

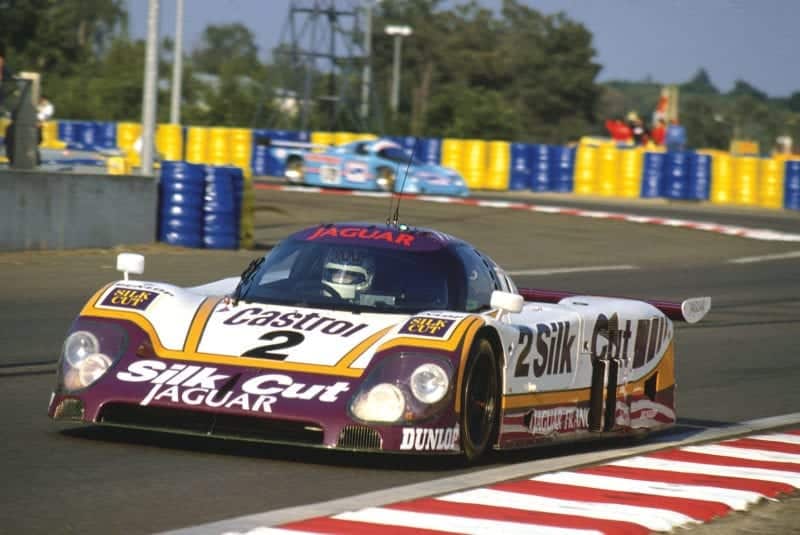

First Le Mans win in 1988 with Jaguar

Motorsport Images

“When John Surtees left to form his own team, Pedro Rodriguez joined as No1 driver for 1970. The P153 was my first BRM design, and the muddy BRM green was replaced by the colours of our new sponsor, Yardley: white with black, brown and gold stripes. The V12 engine was the same weight as a DFV and had the same power, about 430bhp, but with less torque. It revved higher and was thirstier, so we had to carry 48 gallons when the Cosworths managed with less, giving us a heavier startline weight. At irst we had some reliability problems, which we solved with a better oil system. In the Belgian GP Pedro took the lead from Chris Amon’s March and held him off to the end, averaging 149.9mph around the old Spa. Chris sat behind him waiting for the BRM to blow up, and it never did. Afterwards Robin Herd of March put it about that Pedro had a 3.3-litre engine, which upset me a bit. We’d never have done that: for one thing, we didn’t have the budget. As it was, we’d take each engine to bits after every race and, if the pistons and valves looked OK, we’d put them back in again.

“Pedro was popular with everyone. He had this air of mystique about him: small, dapper, quiet, he’d wear English tweeds and a deerstalker hat, and never talk to anyone until he’d combed his hair. He wasn’t a technical driver, he’d just get in and drive his heart out. Alongside the P153 I got sucked into doing a Can-Am car, the P154. There was no time, and it was thrown together and sent to America for the mechanics to sort out on the hoof. It didn’t go very well in George Eaton’s hands, so for the last two races we put Pedro in it. After coming third at Riverside, he told me it was the worst car he’d ever driven. That really embarrassed me. He was always so brave and uncomplaining, so it must have been really bad. For 1971 I re-engineered it as the P167, and it was much better. Pedro wanted to race it in July at the Norisring, but at the last minute we had an engine problem. We only had one engine, so I phoned Pedro to tell him we’d be non-starters. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘I’ve been offered £1500 to drive one of Herbie Müller’s Ferraris.’ That was the car he died in.

“Jo Siffert had joined BRM for 1971. We didn’t treat Pedro and Jo as No 1 and No 2, but as Pedro was there first he felt like the team leader. But when he was killed Jo rose to the occasion at once and seemed to go quicker. He qualified in the top three for every remaining race that season except one. He won the Austrian GP from pole, and he was second at Watkins Glen.” Then tragedy struck again. In the end-of-season race at Brands Hatch Siffert veered off the track in the dip before Hawthorn Bend and hit the bank. The car turned over and caught fire: almost uninjured, Siffert was burned to death. Later it was found that a tyre had moved on the wheel rim and abruptly delated.

Invitation to join Lotus meant working with the revered Chapman

Motorsport Images

“The 1971 car, the P160, was a reined version of the P153. With Siffert’s win in Austria, Peter Gethin’s win at Monza and our podiums at Zandvoort and Watkins Glen, we ended up second in the Constructors Championship, ahead of Ferrari. For 1972 Big Lou had us running five cars, which was a pain in the neck, and during the year we used 10 different drivers. As well as being the designer during the week, I was race engineer at weekends – on all five cars. The sponsor was Marlboro now, and we ran the P160B, the old P153, and the new P180. The DFV had moved on and had more power, but we’d stood still. To make up for our lack of horsepower I pushed the boundaries with the P180, and decided we needed front/rear weight distribution of 33/67. But I went too far, it was 30/70, and with its wide track it was slower than the P160 in a straight line.

“Jean-Pierre Beltoise had joined us from Matra, and he scored a stunning victory in the pouring rain at Monaco. JPB was always easy to work with, no prima donna stuff. He had limited movement in one arm, legacy of a bad shunt in his motorbike racing days, and we had to shape the monocoque in the cockpit to clear his elbow. He led the race from start to inish, lapped everybody at least once except the acknowledged rain-master Jacky Ickx in the Ferrari – and Ickx was nearly 40sec behind at the lag. To do that around Monaco was nothing short of brilliant.

“At the end of 1972 the writing was on the wall for BRM, because there was no budget for a badly needed new engine. Jackie Oliver, whom I’d worked with at BRM in ’69/70, had been driving for Don Nichols’ Shadow team in Can-Am, and he persuaded Don to move into F1. He suggested I come on board and design the car, the DN1. I got on fine with Don, but he was always a mysterious, you could say Shadowy, character. He sported a black beard and a black Spanish hat, and liked to tell you about his time in the CIA. George Follmer joined Jackie as No.2 driver. George was 39 and had never done F1, but he just got in the car and got on with it. In our first race, at Kyalami, he finished in the points, and in our second at Barcelona he got on the podium. That rather pissed Ollie off. From then on we had various problems and crashes, and didn’t score another point until Jackie was third in Canada. Don also insisted I did the DN2 Can-Am car. His engine man came up with a 1200hp twin-turbo Chevy V8 which he said was going to win everything, but my sums said it’d do 2mpg. I drew a big car with fuel stuffed in every corner, and massive drive shafts to cope with the power.

But that engine blew up every time you looked at it. We had to run with a normal V8 and it was just too big and heavy. For 1974 I said to Don, ‘let’s do Can- Am right’, and I did the DN4: smaller, neater, better-packaged, and Oliver won the title.” To drive the 1974 F1 car, the DN3 – “much better, much nicer than the DN1” – Shadow hired Peter Revson and Jean-Pierre Jarier.

Wingless Arrows A2 had great downforce…

Motorsport Images

“Revvie was a fabulous easy-going guy, fitted in well, and a very good driver. But tragically he wasn’t with us for long. He qualiied on row 2 for Argentina and row 3 for Brazil. Then he and I, our chief mechanic Pete Kerr and two other mechanics went down to Kyalami for testing before the South African GP. Revvie was going well, very happy with the car, and then he didn’t come round. We rushed out to the back of the circuit and found the car buried under the Armco on the outside of a quick corner. Peter was already in the ambulance and gone. I phoned the hospital, and they told me I had to go to the morgue and identify him. When the news got out all hell let loose, journalists banging on my hotel door, then the Revson family lawyer arrived and took over.

“We were using titanium quite a lot on the DN3, which was quite a new material then. Titanium is finicky, it has to be machined smooth and the surface polished, and a ball joint which had some coarse machining on it had failed. There was only one layer of Armco and the car, instead of being delected or stopped, had gone right under as far as the cockpit. I felt personally responsible. It was a very dificult time. The glamour of Formula 1 had gone, replaced by a sort of loneliness. You just had to work on. Of course I replaced all the titanium components with steel before the next race.

…But soon grew rear wing due to handling quirks

Motorsport Images

“Jarier oozed natural talent, but he was lazy. He’d do his quickest lap straight away, then he’d want to go home. In testing you had to suss out what was needed within the first five laps, because after that he’d adapt to whatever the car was doing. At Dijon he came in and said, ‘not bad, but it’s understeering on the long right-hander.’ Next time he came in I said, ‘how’s the understeer?’ ‘It’s ine.’ In the debrief I asked him why he’d said it was understeering, then he said it wasn’t. ‘Oh, I just gave it half a turn on the rear brakes’ – making the car slide under braking to cancel out the understeer. I was impressed he could do that, but it would have been better if we’d just dialled out the understeer.

“Tom Pryce joined us after Brian Redman decided not to do any more F1. Tom was young and inexperienced, but always quick: in his second race for us, at Zandvoort, he qualified third ahead of Regazzoni’s Ferrari and Fittipaldi’s McLaren. In 1975 with the DN5 he had pole at Monaco until Niki Lauda pipped him right at the end. Then, for the British Grand Prix, he got pole and kept it – and was leading the race until he hit the rain and went off. He made mistakes, but he learned fast. Just an ordinary bloke, quite shy. Instead of going back to the hotel at the end of the day he’d stay in the garages with the guys doing the work. Everybody liked him. If he’d switched to another team he could have ended up World Champion. But he was so loyal to Shadow: he stayed with them for his entire F1 career until he was killed in that bizarre accident at Kyalami. Two marshals ran across the road with fire extinguishers. Tom, unsighted, came over the brow at full chat and hit one of them, got the extinguisher in the face. A dreadful waste.

“Early in 1976 Colin Chapman summoned me to a meeting at Ketteringham Hall. With everything else he had on his plate, the road cars and the boats, he wanted somebody to sort out the race cars. I was fascinated by Chapman. For me he was the ultimate designer; still is. The chance to work with him was something I couldn’t refuse. Hugely intelligent, way superior to any other designer I’ve ever come across, but always on the ragged edge. Barking mad, really. That seemed to be a Lotus requirement – team manager Peter Warr was pretty mad as well.

Audis in echelon: 2000 brought first Le Mans win

Motorsport Images

“I was the chief engineer. I didn’t draw while I was at Lotus: they had Martin Ogilvie, who was a beautiful draughtsman and a bloody good designer, plus Ralph Bellamy and Geoff Aldridge, and Peter Wright doing aerodynamics. That year’s F1 Lotus, the 77, was a bit messy, but we nibbled away at its problems, and Mario Andretti won the last race of the year in Japan. Mario was just wonderful. Everything you hear about him is true. He liked Lotus, he liked Chapman, and he always gave ten-tenths without question. He won in Japan by staying on wets when everybody else changed to slicks. There was canvas showing all round the left-hand front tyre, but he just went for it. Brave: as they say in America, ‘balls on the hood.’

“For 1977 we had the 78, with all its massive downforce. Skirts took over my life: first we had nylon brushes, then hinged polypropylene, then sliding panels. At the races Colin engineered Mario’s car himself, and Mario won four Grands Prix; I engineered Gunnar Nilsson’s, and he won at Zolder. In the cockpit, poor Gunnar hated having his crotch straps done up too tight. He was in pain, but there was no way he was going off to a doctor in the middle of his season. Unknown to him and us, he was developing testicular cancer. Once it was diagnosed he bore it with immense courage and good humour, but very sadly he died the following year.

“My contract with Lotus was just for 18 months. Soon Don Nichols was telling me that Shadow had a load of money now, James Hunt was going to drive for the team, all that. So I rejoined Don, Jackie Oliver and Alan Rees and started drawing the 1978 F1 car, the DN9. Within weeks I realised it was a lot of waffle and nothing had changed. Then Ollie said, ‘This is no good. I’m going to start my own team. Reesie is coming too, why don’t you join us?’”

Arrows was set up at the end of November. Riccardo Patrese moved across from Shadow too, bringing his Italian sponsor Franco Ambrosio. Within 53 days the first Arrows FA1 was being lown to the test at Rio, and barely a week later Patrese raced, and inished, in the Brazilian Grand Prix. For the South African GP at Kyalami there were two cars for Riccardo and Rolf Stommelen, and Riccardo was leading when his engine failed with 15 laps to go.

Having already done much of the design work on the Shadow DN9, Tony had produced the FA1 very fast, and inevitably there were similarities, particularly in the suspension and hub assemblies. So Don Nichols – who had lost most of his staff when Arrows was set up – sued for breach of copyright.

Free hand for Ford’s GpB car brought RS200

Motorsport Images

Meanwhile the Arrows was going well: Patrese finished second in the Swedish Grand Prix to Niki Lauda in the notorious Brabham fan car. While the Shadow/Arrows litigation dragged on, as a contingency Tony started on another design, slightly different in every dimension. In great secrecy two cars, called A1s, were built, sharing no interchangeable parts with the FA1.

The court verdict was due just before the German GP, so the two A1s were taken to Germany in a plain van and hidden in a lockup close to Hockenheim, ready to be used if a losing verdict came before the race. As it was, the verdict came on the Monday after. A court injunction prevented Arrows from using the FA1, so the A1s were brought out of their German hiding place and taken straight to the Zandvoort test on the Tuesday. Seeing them there, Nichols assumed they were the FA1s and the injunction was being louted. Back at the factory a posse of lawyers arrived – only to retire meekly when they realised the A1 was different in every key respect from the FA1. “All Don Nichols got was £1000 for the breach of copyright and £25,000 for loss of earnings. But Arrows’ legal costs were £250,000, so we were in the red from the start. Then Ambrosio was jailed for various financial misdeeds. Arrows didn’t have an easy birth.

“All this time I couldn’t fault Riccardo Patrese. He ticked all the boxes: fast, intelligent, brave. People said he was arrogant, but he wasn’t: he was shy. James Hunt blamed him for Ronnie Peterson’s fatal crash at Monza in 1978, and everybody believed Hunt. But a long time later I saw a sequence of photos of the start. Riccardo was coming up on the extreme right, and didn’t touch anybody. Ronnie, who was moving diagonally across the grid after a bad start, collided with Hunt. They stopped the race, and when Riccardo came back to our pit we put fresh rubber on for the restart. Emerson Fittipaldi saw this and put it about that we’d changed the wheels because they showed signs of a collision with Hunt. That is absolutely untrue. There wasn’t a mark on them. But, totally unjustly, Patrese was demonised, and actually banned from the next race.

Tom Pryce put Shadow DN5 on pole at 1975 British GP

Motorsport Images

“With the A2 I tried to be really different. I did some serious wind-tunnel work and it was producing massive downforce, 50 per cent more than a normal car without using a rear wing. But to get the shape underneath I had to tilt the engine, and that made the centre of gravity too high. It didn’t like rapid changes of direction, quick left-rights. If we’d put very stiff springs on, like Williams did later, it might have worked. The A3 for 1980 was conventional, nice and neat, and Riccardo was second at Long Beach. But the problem was just as it had been at Shadow – no development money. Jackie Oliver was desperate to keep the German sponsors, Warsteiner, and he suddenly announced he was hiring Gustav Brunner and some German engineers. I said if he did that he’d be doing it without me, and he said, ‘Fine.’ So I picked up my briefcase and left. Gustav did go there but didn’t stay long, and Ollie lost the Warsteiner sponsorship anyway. I had a 10 per cent shareholding in Arrows: Jackie managed to get the whole team valued at just £50,000, so I only got £5000 for my shares. Looking back, I regard the whole Arrows thing as a wasted period in my life. It was a great relief to be out of it.”

Tony spent the next two F1 seasons with Teddy Yip’s little Theodore team, working with Patrick Tambay, Marc Surer and Derek Daly. Then he made his first move into sports cars, designing the Mk3 version of Ford’s C100 Group C car with turbocharged Cosworth DFL. Internal Ford politics axed it before it had raced, but it led to an invitation from Stuart Turner to pitch for a Group B rally car. “He said I could do anything I liked, put a DFV in it if I wanted. I went for an aluminium honeycomb chassis, turbo BDA mounted in the middle but offset to the left, transmission alongside the engine and four-wheel-drive. I’d never been involved in rallying, and all the criteria were different – manoeuvrability, ground clearance, suspension travel, the need to carry two people and change parts very fast at service points. I loved the challenge of all that. I won the contract and my design became the Ford RS200. The first eight were made at Auto Racing Technology, the company I set up with John Thompson in Wellingborough, and Reliant built the 200 production cars for homologation. At the end of 1986 the FIA killed Group B, but Mark Lovell used an RS200 to win the British Championship.

Southgate with Shadow’s John Nichols

Motorsport Images

“By then I’d moved on to TWR. Tom Walkinshaw asked me to design a Le Mans car for Jaguar – a real Jaguar because it had a proper road-car engine, that big lump of a V12 which you can ind in any old XJS. The way to get more power was to bore it out. We started with 6.0 litres, then 7.0 and eventually 7.4, and got 740bhp. It was always two valves per cylinder; we tried four-valve heads, but because of the extra weight it was slower. The car we had to beat was the Porsche 962. Porsche had reliability, but to me their chassis weren’t very strong. The Jaguar was designed as a hugely rigid carbon-fibre structure, with the roof part of the chassis. When Win Percy went end-over-end at 200mph, he undid his seat belts and got out unhurt.

“It took us three years to get our irst Le Mans win. It was all a massive learning curve. To get down that Mulsanne Straight quicker than anybody else we needed 240mph, and once we got it we had to retain it as brake ducting and oil radiators got bigger. Among the drivers Martin Brundle felt he was the No 1, and he was always quick. But allocating three drivers to each car we had to make sure they suited each other. In 1988 Jan Lammers/Andy Wallace/Johnny Dumfries were the fun team, jokey characters but serious underneath. In the closing stages Jan, in the lead, felt the transmission go funny. He managed to select fourth gear, and radioed in telling us he wanted to stay in the car to the end. But he didn’t say what the problem was, in case the Porsche guys were monitoring our radios and might speed up Stuck in the second-placed car. He left it in fourth for the rest of the race, even chugging out of the pits after a stop, slipping the clutch and with everybody pushing. He made it to the end, and we’d won Le Mans at last. When we took the gearbox to bits the pinion shaft was completely broken, but fortunately in the middle of a hub with about 15mm of engagement on the splines both sides, so it still drove.

“I did the XJR10 and XJR11 with twin-turbo V6, and at Le Mans in 1990, with the V12 XJR12 and the modified circuit with chicanes, Brundle/John Nielsen/Price Cobb led home a Jaguar 1-2. Then I went to Toyota for three years until the end of Group C, dividing my time between Japan and England.” In 1992 the V10 Toyota TS010 was second at Le Mans first time out, but the transmission was the car’s Achilles heel. Tony was then hired by Luca di Montezemolo as design consultant on the Ferrari 333SP customer sports-racer, before helping the ebullient Laurence Pearce take the Lister Storm to Le Mans. Next it was back to Tom Walkinshaw on the Nissan R390 Le Mans programme. When Nissan’s financial troubles and subsequent amalgamation with Renault wound that up, Tony’s now considerable Le Mans experience was taken on board by Audi. He became deeply involved with Ingolstadt’s parallel R8C and R8R development, which brought third and fourth places at Le Mans in 1999. In 2000 came the magnificent 1-2-3 for the R8, the first of Audi’s string of Le Mans victories. And after that Tony, now 60, retired.

But he couldn’t stay away from motor sport. He rejoined the 750MC, and went club racing with a Sylva kit car. “It cost me £15,000 – about the same as a front upright for an Audi R8! I had a lot of fun, doing the Six-Hour Relay five times. Motor sport has changed so much, yet the camaraderie in the club is just as I remember it. I’ve sold the Sylva now, but the 750MC has done me the honour of making me club president, succeeding the late Bill Boddy.

“When I was in F1, I could always tell a car’s designer: like a signature on a painting, a Brabham would say to me Gordon Murray, a Tyrrell would be all Derek Gardner, I’d look at a Lotus and see Maurice Philippe. You don’t get that with CAD [computer-aided design]. CAD’s great, but it’s only a tool. Now the individuality is gone, because everybody uses that same tool – apart from Adrian Newey. Adrian still puts pencil to paper: he probably has the last drawing board left in F1.

“I’m lucky to have been working in that magic period started by Chapman and Broadley. You’d pick up a pencil, put a sheet of paper on a board, and draw a car. The thinking went straight from your brain through the pencil to the paper: the car came to life as you drew. And, good or bad, it was your car. Nobody else’s.”