There followed a brief flirtation with Ferrari, starting with the test of a sports car intended for Le Mans (nothing came of it) and then an invitation to test an F1 car as a possible temporary replacement for an unwell Gilles Villeneuve (the Canadian quickly recovered). Elio was asked to sign some papers, although it seems not to have been a full-blooded commitment, as he told me a couple of years later. “The document I signed in Maranello wasn’t a full contract, although I was given the opportunity to test with Ferrari. I drove their F1 car on several occasions. Looking back, I think it was just a question of luck I didn’t race one of their cars. I came close in 1978: if Gilles had had one more accident, I would’ve been given his place in the team.

“I have to admit there cannot be many 19-year-old drivers who have quit Ferrari”

“In Italy, when a team is going through a bad period, there is a tendency to look at the driver before anything else. I realised that my position with Minardi was in danger, and I decided to leave. I spoke to my father about it first and he advised me, ‘You can’t do it, you have a contract,’ but I did. I knew I was taking a risk with my career, but I had to do it because I knew I’d be able to do well with an English team. So I drove one of the ICI F2 cars, and immediately I knew I’d done the right thing. But I have to admit there cannot be many 19-year-old drivers who have quit Ferrari. As I said, it was a matter of luck that it paid off. You’re always alone when you make the big decisions of life: now, fortunately, even my father agrees that what I did was right for me.”

By the end of ’78 the precociously talented Roman had come to the attention of several more F1 teams, including Brabham, with Shadow inviting him to test at Silverstone in September. The first team owner to get the de Angelis signature on a contract, however, was Ken Tyrrell, although he must have known that his new recruit had not done enough in F2 to be sure of obtaining the Superlicence necessary to race in F1. Eventually the CSAI (Italian sporting authority) intervened to ensure a Superlicence was issued, allowing an agreement to be reached with Shadow, supposedly just for the first half of the ’79 season.

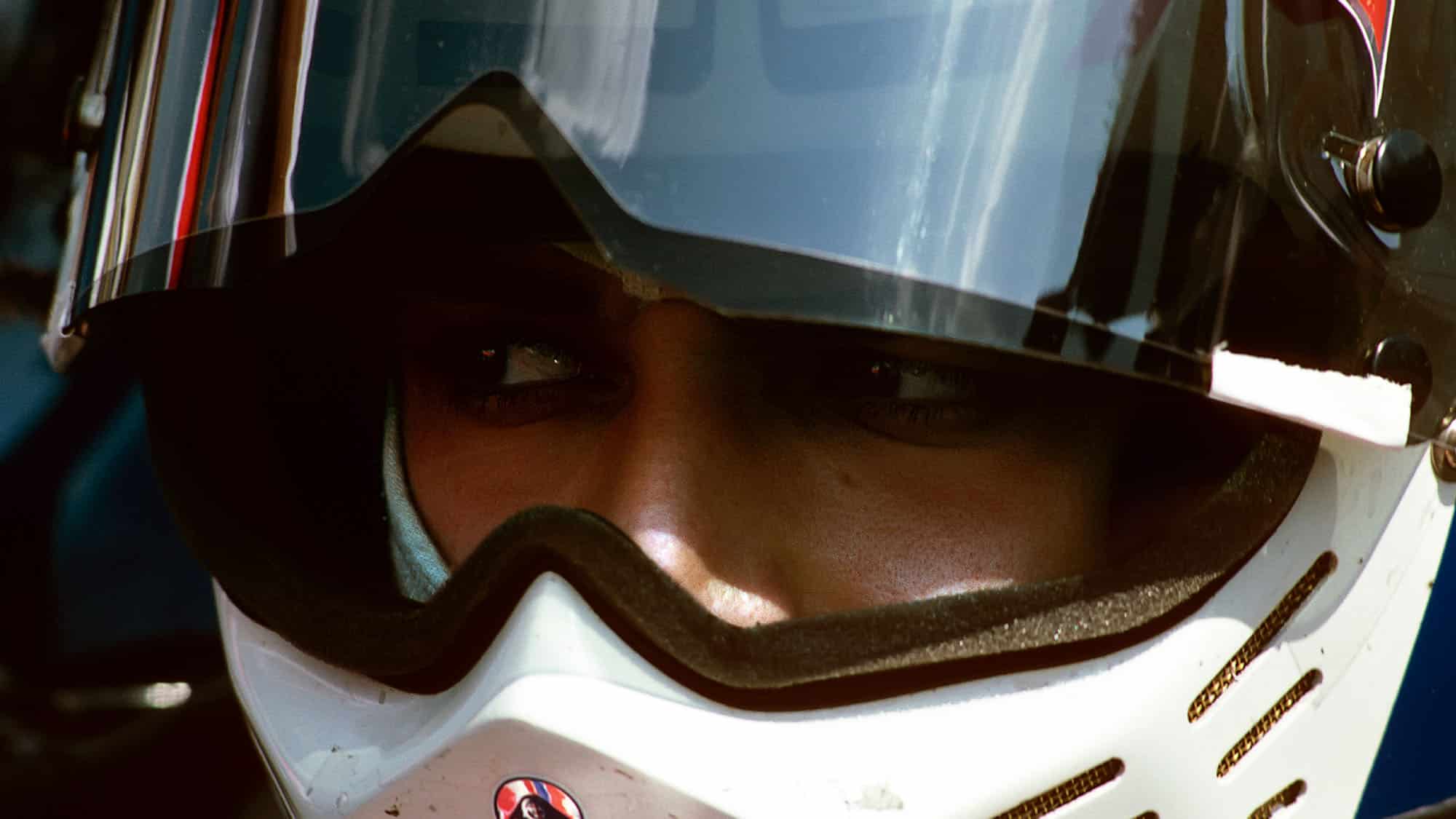

Testing the stillborn 88 early on in his Lotus career

Grand Prix Photo

Still not 21, Elio was firmly on the F1 radar, although the combination of inexperience and Shadow’s outdated equipment stood in the way of hard results. Eventually team owner Don Nichols took advantage of the fact that Elio was behind with his payments to push him into a long-term deal as a paid driver. The first eight races still had to be paid for, though, for which Elio had to borrow money from his father. He made sure that those close to him were aware he’d been punctilious about repaying it, which he was eventually able to do from his Lotus earnings.

The hurriedly concluded Shadow deal turned out to be legally inconvenient when Colin Chapman, in search of a replacement for Carlos Reutemann, organised a test at Ricard at the end of 1979 in which five young drivers — Elio, Nigel Mansell, Stephen South, Eddie Cheever and Jan Lammers — were invited to take part. Even though Elio was quickest on the day, Chapman favoured the two Brits. But he had recently done a big-money sponsorship deal with the American-born oil trader David Thieme — a self-publicising rascal with seemingly limitless resources — and Thieme liked the idea of employing the debonair de Angelis with his tanned good looks and sophisticated tastes. Chapman could hardly refuse, having already been dropped by long-term sponsor John Player and having rejected an extension of a deal with the Martini & Rossi liquor giant.