Lunch with... Jackie Oliver

This Essex lad is more proud of his record as an F1 team owner than of his achievements behind the wheel. But those were varied and significant, too.

James Mitchell

The sharp, punchy little guy from Romford has a downbeat view of his own racing career. He led his first home Grand Prix, and was set for a fairytale win when the car failed. He scored a historic Le Mans victory for Ford. He did 50 Grands Prix for Lotus, BRM, McLaren and Shadow, won a string of long-distance sports car classics, and was Can-Am Champion. But he regards himself as the man who finished third. “Look at the books, you’ll see: my best placings were usually third.” He is much prouder of his record as a team owner with Arrows. Set up amid controversy and legal attack in 1978, it remained part of Formula 1 for more than two decades. “I ran that team with prudence, always intent on survival. I kept it going for 22 years. Tom Walkinshaw buried it in three.”

A favoured only son with four elder sisters, Jackie was a tearaway as a lad. His father had a prosperous refrigeration business. “He liked what we’d now call supercars – 300SL Gullwing, Ferrari 250, BMW 503. He had factories across Essex, and all along the Southend Road there were car dealers. They’d put something smart out on the forecourt, and rub their hands when my dad came along. When I was a kid, underage and no licence, I used to nick his car when he’d gone to bed. I’d scoop the keys out of the cut-glass bowl in the hall, open the garage doors, roll it back onto the road, start it up, and go and show off to my mates in the Green Tiles Café. Race up and down the Southend Arterial Road in the middle of the night. I remember peering through the steering wheel of his Facel Vega because I couldn’t see over it. I think Dad knew what I was doing, I reckon he was just lying in bed waiting for the phone call. The hard thing was getting back into the garage, because it was uphill from the front gate. I had to come roaring down the road, switch off, and swing in the gate fast enough to coast up into the garage. Then slip the keys back into the bowl in the hall.”

As soon as he was old enough for a competition licence there was the inevitable 850 Mini, driven on the road to race at Brands and Snetterton. “Then I said to Dad, ‘Can’t I have a proper racing car?’ So he bought me a Marcos. I totalled that at Snetterton, reduced it to a pile of matchwood. He bought me another Marcos, and we built a little Diva. My dad’s business partner, Ken Baker, raced an E-type and a Mustang, and I drove those as well. Then we got a full-race Lotus Elan, one of the proper 26Rs.” With the Elan Jackie clocked up a lot of wins, and really got noticed. “In 1966 Andrew Ferguson, the Lotus team manager, gave me a Formula 3 test at Silverstone and I went as quick or quicker than the regular drivers, so he signed me for the F3 team, Charles Lucas Team Lotus. In 1967 I did F2 in the Lotus Components spaceframe 41, but they also put me in the Team Lotus monocoque 48 when Jimmy [Clark] or Graham [Hill] wasn’t available.”

That year F2 cars ran in the German GP to make up the numbers around the Nürburgring’s 14 tortuous miles, and Jackie brought his 48 home a remarkable fifth overall. With John Miles – “a good driver, but a very dour personality” – he won his class in the BOAC 500 at Brands in a Lotus 47, and he stood in for Clark in the works Lotus Cortina in major British events. And whenever there was a Lotus to be tested he did it, including the F1 car. Then came April 7, 1968. Jackie was at Brands for the BOAC 500, sharing the 47 with John Miles again, and once more winning the class. Clark and Hill were at the F2 race at Hockenheim with the 48s – and Clark was killed.

Oliver impressed with fifth overall in Lotus F2 car at 1967 German GP

Motorsport Images

“Andrew Ferguson liked how I was going, and [race engineer] Jim Endruweit was a big fan, but Colin Chapman didn’t want to know. He was only interested in Jimmy and Graham. Colin was impossible, a whirlwind, all over the place. Then Jimmy died, and he was even worse. His best driver, his best mate, was gone.” For six weeks Chapman refused to make a decision about another driver, and at the next two F1 races Hill’s was the only Lotus.

“Then it was Monaco. They had to run a second car, so Jim Endruweit said to Chapman, ‘Put him in.’ Monaco isn’t exactly the place you’d choose for your first F1 race. Before the start Colin bent down into the Lotus 49’s cockpit and said to me, ‘Lad, in the whole history of this race there have never been more than six finishers.’ Not quite true, but I got the point. Whatever I did, I had to finish. First lap, coming out of the tunnel – lit by about one 25-watt bulb in those days – into the bright sunlight, Bruce McLaren hit the barrier and tore off a wheel. Scarfiotti’s Cooper slewed sideways to avoid him. I arrived and had nowhere to go. Tore two wheels off. Lap one. I walked back to the pits. Colin, bent over his lap chart, didn’t even look up. ‘You f***ed that up, didn’t you. You’re fired.’

“Not a long F1 career. Half a lap. But Endruweit talked Chapman round, they built up a new car for me, and two weeks later I was at Spa. Friday was dry, but my car hadn’t arrived. Saturday I had the car, but it was raining.” Jackie has modestly chosen to forget that, around the old Spa in a new and untried car, he was third-quickest in the wet, 0.7sec slower than Pedro Rodríguez. In the race he had a clean run to fifth place. At Zandvoort he was delayed by wet electrics, but finished, and then came Rouen and the French Grand Prix.

Suddenly high wings had arrived in Formula 1, and the Lotus 49s turned up at Rouen with wide rear aerofoils on tall struts bearing directly on the rear suspension uprights. The wing on Graham’s car was big, but the one on Jackie’s car was immense. “There was never any question of going testing with any new bits. Colin would have an idea, and insist it was on the cars for the next race. So there was this giant wing above the back of my car. I was the test rig. Stick it on Oliver’s car and see what happens. I looked at this thing up there on stalks, nobody in the team could tell me anything, so I went and asked Chapman what it was all about. ‘Aerodynamics, lad,’ he said, ‘It’s the future.’ I gave one of the struts a push, and it moved from side to side. I said to Chapman, ‘Is it meant to do that?’ He said, ‘You know when you look out of the window of a Boeing 707 and you see the wings flapping up and down? It’s the same. It’s got to be flexible so it doesn’t break.’ I said, ‘Oh, OK’, and out I went. There was no, ‘Go out, do one lap, come in for a check.’ It was, ‘Go out and get on with it.’

“So off I went, and the grip was unbelievable, grip I’d never experienced before. On my third lap I was flat out past the pits behind Richard Attwood’s BRM. He moved aside to let me past, and suddenly I swapped ends. What I think happened was, in the turbulent air behind the BRM the wing collapsed, fell over backwards and lifted the rear wheels off the ground. That was the start of an almighty accident. Opposite the pits there was a brick parapet, and I hit that, and it tore the gearbox and rear wheels off the back of the engine. When the dust had settled I was standing there shell-shocked beside the wreckage opposite the pits, and Chapman ran across the road and said, ‘What happened? Did you hit something?’ I was so intimidated by Chapman, and I knew the worst thing a driver can do when he has a crash is blame the car, but I said, ‘No, I didn’t.’ Later he said, ‘You idiot, you hit that parapet, didn’t you?’ ‘Yes’, I said, ‘But that wasn’t what caused the accident.’

Derek Warwick in the Arrows at Monaco ’88 – “the best driver” Oliver ever had

Motorsport Images

“Two weeks later it was the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch. Chapman had promised Rob Walker a new 49B for Jo Siffert, but it wasn’t built, so he lent Rob the car intended for me. I had to make do with the old Walker 49, which Lotus borrowed back and painted red, white and gold. It had the earlier rear suspension, which used to toe-out under load.” On familiar ground after years of racing at Brands, Oliver qualified in the middle of the front row, led the race from the start, let team leader Hill past and, when Hill retired on lap 26, drew away in an ever-increasing lead. It was his fourth F1 race.

“The Cosworth DFV used to breathe very heavily back then, and there was a big pipe on top of the engine which circulated oil via a catch tank back into the engine. A mechanic had routed the pipe the wrong side of the exhaust manifold, and it melted. Blew the oil out, and did the engine in. I stopped just after half-distance, and Siffert won. I don’t remember feeling gutted: it was just another race, really. My performance didn’t alter my relationship with Chapman.

He liked to think that a problem with the car was a problem with the driver, especially with drivers he didn’t fully support. Graham used to go through hell with that. It was only with Jimmy, or Jochen, when he knew he had a quick driver, he’d get fully involved. He never thought Graham was quick enough. Beside Jimmy no one was quick enough – well, Jochen was, he was very involved with Jochen. He wanted Jackie Stewart, but Stewart refused to drive for him because he thought Lotuses were too fragile.

“I got third place in the Mexican GP at the end of the season, but BRM had come after me and I’d already decided to go with them. Colin only wanted to use me when it suited him, and he’d got Rindt signed for 1969, whereas BRM was a full-time drive alongside John Surtees. But that first year, before Tony Southgate got there, the BRM was an old-fashioned disaster. Surtees and I never got on. He was selfish: ‘I’ll take that car, with that engine, and the gearbox out of Oliver’s car.’ He would deliberately try to reduce his team-mate to one of the lower orders, and I never got the updates. But I learned from John that you have to drive a team hard, to get them to produce a better car for you. And he was instrumental in getting Southgate to join.

Jackie is a keen historic racer, this is the St Mary’s Trophy at the 2008 Goodwood Revival

Motorsport Images

“For 1970 we had Southgate’s new P153, and my team-mate was Pedro Rodríguez. I got on with Pedro very well. He was quiet, never used to say much. Of all the team-mates I had, Graham Hill and Pedro were the easiest to work with. But in the P153 I almost never finished races. I had a string of problems. In the end I told Louis Stanley what he didn’t want to hear. I said he had the wrong team manager [Tim Parnell], and he said, ‘Well, if you can’t work with him there’s no room for you here.’ Stupidly I had that row before I’d got a deal done for the next season. That taught me a lesson.”

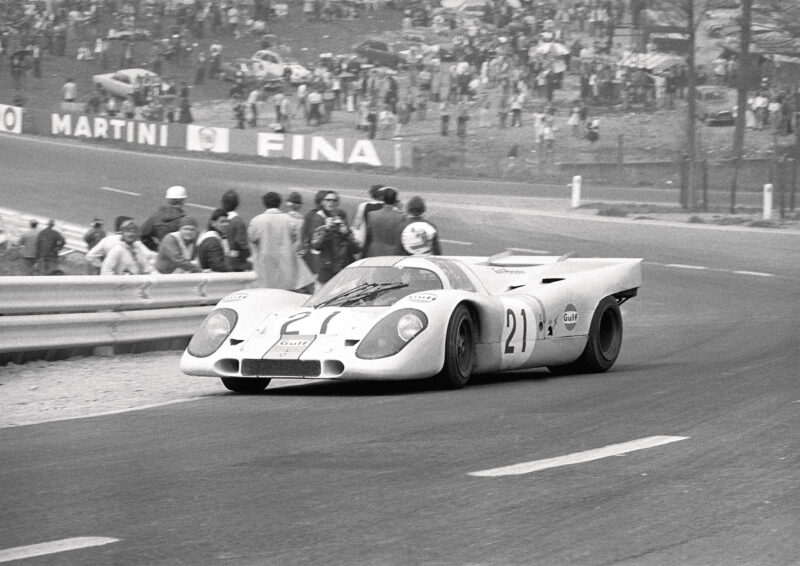

Thereafter Jackie’s F1 career faltered. He had a few drives for McLaren in 1971, helped by Peter Gethin’s mid-season move to BRM. But his hopes for a permanent McLaren seat foundered when Peter Revson opted for F1 over USAC, and his only 1972 Grand Prix was for BRM at Brands Hatch. Meanwhile he’d been building a strong reputation in sports car racing. He’d first driven for John Wyer’s Gulf GT40 team at Le Mans in 1968, and in ’69 he did a full season, paired with Jacky Ickx. They won the Sebring 12 Hours and then, famously, the Le Mans 24 Hours.

“Ickx, along with Surtees, was the most difficult team-mate I ever had: totally self-centred, trying to corral the whole thing around himself all the time. But I accepted it, because if you complain you just put yourself in a bad light. The team thought he was the No 1 driver and I was the No 2, so I performed the second driver role to keep the peace. I got pissed off with it in the end. John Wyer wanted me to stay for 1970, but I said I didn’t want to do sports car racing any more.

“He came back with a lucrative offer for 1971, partnering Pedro in the 917 Porsches, and because the money was good I accepted. We won the Daytona 24 Hours, the Monza 1000Kms and the Spa 1000Kms.” Jackie also clocked the fastest lap ever around Le Mans during the April test weekend at an average of 153.53mph, doing well over 240mph on the old Mulsanne Straight, and in the race itself he left the official lap record at 151.8mph. Subsequent circuit changes mean these marks still stand. “But once again Pedro was the No 1, I was the No 2. I had a lot of other things going on in my head, things I wanted to be getting on with. So I walked. At the end of June I was due at the Österreichring 1000Kms, but instead I went to the Can-Am round at St Jovite to drive the new Shadow.

Oliver mixed single-seater success with sportscars before moving into team ownership

Motorsport Images

“When I didn’t turn up in Austria they tracked me down to my hotel in Canada. Grady Davis of Gulf called and said, ‘What are you doing? Why aren’t you here?’ I said, ‘I don’t want to drive for your team any more. I’m fed up with it. I don’t like the way you treat me, picking me up and putting me down when it suits you. I’ve got something else I want to do.’ Then [JW team manager] David Yorke came on the phone, absolutely ballistic. He said, ‘Oliver, that is the last thing you do in motor sport. I am going to ruin you.’ ‘That’s fine, David,’ I said, ‘Give it your best shot.’ Looking back, it wasn’t the right way to behave, but I felt I had to do it.”

Jackie had been doing the Can-Am series since 1969. His first ride was in the Autocoast Ti22, designed by US-based Englishman Peter Bryant (Motor Sport, April). At St Jovite the air got under the Ti22 at over 150mph at the notorious Hump, and it reared up vertically before crashing down on its back. The car was destroyed but, just as at Rouen two years before, Oliver was miraculously unhurt.

“Don Nichols turned up in Can-Am in 1970 with that stupid car with tiny cotton-reel wheels, the first Shadow. He approached me, but I told him his car was rubbish. I said, ‘You’re going to run out of money with stupid projects like that. What are you doing, spending your own money on racing? Get yourself some sponsorship, and get Peter Bryant to design you a conventional car.’ So he did. The money came from Universal Oil Products, who were into oil refinery technology. That was the start of my relationship with Don.

“He was an unusual man. When he was small his parents were killed in a car crash – he was in the car, but survived – and he was brought up by his grandmother. In the 1930s there was a radio serial in the US, rather like Dick Barton in the UK, called The Shadow. The Shadow wore a black cloak and a black hat, and the catchline was, ‘Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows.’ Don loved that as a kid, so when he came into racing the cars were called Shadows. They were black, and Don wore a black cape, a black beard, a black toreador hat and dark glasses. Different…

In tricky high-wing Lotus 49 for the 1968 British GP, ahead of team-mate Hill

Motorsport Images

“I was now nearly 30, and for a while I’d been thinking about running my own team in F1. I told Don it had to be in England, because all the knowledge and the good people were there. We set up in Northampton, and I pulled in Tony Southgate to design the car and Alan Rees to run the team. Don wanted an American in one of the cars, so the drivers were me and George Follmer. Poor old George hated me. I had the advantage of knowing the circuits and I kept on being quicker than him, and at the end of the year he went back to America.”

Shadow’s first F1 season was 1973 and, apart from a strong third from Follmer in its second race, at Barcelona, it had little to show in the way of results. Then at the confused Canadian GP, after bungled use of the pace car, Oliver got third place. Some lap charts said he was second; some even said he’d won. “After that I decided to stop driving in F1. I was pretty much heading up the team and running the factory, and Alan said to me: ‘Do you really still want to do this?’ He could see I wasn’t quick enough any more, and that I had too much on my plate. But I was still hooked on the nicotine of racing, so I decided I’d do F5000 in the States. I was still doing Can-Am too. The F5000 car was just a Shadow F1 with a Chevy, and later a Dodge, in the back. The weight distribution of that was never right. And we were up against some good people – Andretti, Redman, Scheckter, Unser. I kept finishing third, as usual.” But in 1974 Jackie dominated the Can-Am series, winning the title, with Shadow team-mate Follmer runner-up.

“I spent a lot of time going backwards and forwards across the Atlantic. I had houses in Surrey and California, and it wasn’t good for my marriage. When I was at Lotus I’d married one of the Gold Leaf promotion girls, Lynn, and while I was in America she went off with a pop star. Ironically, it was one of the Shadows… Later on I got carried away with Lulu, a dancer from Legs & Co, and I married her. But I was away too much, and she went off with my next-door neighbour.

“I’d been doing Roger Penske’s IROC Series with the Camaros, and I had an offer to do the Indy 500. But I used to have a lot of accidents in those days, and at Indy any accident is at 200mph. So I turned it down. Then Bill France of NASCAR found he needed an FIA-graded driver for his events to be officially rated as International. Jabby Crombac, who’d been a supporter of mine since my Lotus days, suggested me. I went down to see Bill, and told him I wanted $1000 a race and $1000 expenses. He said, ‘That’s a helluva lot of dollars, young man.’ But the deal was done, and I got $24,000 for 12 races plus a percentage of any prize money. Not bad for those days.

“But NASCAR, that was a learning curve. The guys called me the Little Limey, and the only thing that impressed them was my ability to control a slide. The rest of it, I was rubbish. I had plenty of accidents, 180mph backwards into the wall, but I never hurt myself. It was all ovals, the big superspeedways, and the little mile ovals. With those you’re always in a bloody corner. My pec size went up an inch and a half. Everybody used to cheat like hell, and the only sin was getting caught. Most of the races were in the Deep South: a barbecue on a warm evening around the pool at some Holiday Inn, somebody playing a guitar and all the drivers singing Country & Western songs. It was a long way from F1.”

Dominant ’74 season in Can-Am aboard Shadow included a win at Watkins Glen

Motorsport Images

Shadow started the 1974 F1 season with Revson and Jean-Pierre Jarier, but Revson was killed testing at Kyalami. “The car broke. It was a lightening hole that was drilled too deep.” After a few races with Brian Redman, Jackie hired Tom Pryce, who made his mark at once. On his second outing, at Dijon, he qualified third behind Lauda’s Ferrari and Peterson’s Lotus. Two seasons later Pryce also died at Kyalami, in that bizarre accident when a marshal ran in front of him carrying a fire extinguisher.

“After Tom was killed Reesy and I went through the list of graded drivers until we got to J. Alan Jones. Whatever happened to him? We knew he’d got fed up with Surtees. We found a London phone number for him, and dialled it. An Australian voice answered. ‘Nah, Jonesy’s gone home. I’m just here to sell the house.’ He gave us a number in Australia, we dialled it, Alan picked up, and we said, ‘Want to do the Race of Champions next week?’ ‘Can’t make it, mate, I’ve got an F5000 race.’ ‘What about Long Beach?’ ‘Yeah, I’ll be there.’ No talk of money, no contract. I did the Race of Champions myself – first time I’d been in an F1 car for nearly four years – and Jonesy joined us for Long Beach. And of course he won in Austria that year, Shadow’s only Grand Prix victory. Third at Monza, fourth at Mosport and Fuji. Then he went to Williams, and three years later he was World Champion. He still says if I hadn’t made that phone call and got him back, it might never have happened.

“Our other driver that year was Renzo Zorzi, but he was completely bloody useless. We’d lost UOP by this time and we were being backed by an Italian financier, Franco Ambrosio. I told Franco I reckoned another young Italian called Riccardo Patrese. Riccardo couldn’t do the Swedish GP because he was already committed to an F2 race, so I had to put my overalls on again for that. Went the distance, finished ninth. Then we had Riccardo. Very quick, very talented, and versatile. Even at 23, he didn’t suffer from temperament like most Italians, he was measured. He ended up driving for me, through Shadow and Arrows, for five seasons.

“It was during 1977 that I had the falling-out with Don Nichols. The deal had always been that I’d be part of the organisation when I stopped driving. I was the sponsorship hunter and I’d found Villiger tobacco, but all the money was going back to the US and not enough was staying in England for the F1 team. I started to ask why we had such a big cost-base in Chicago when we didn’t do anything there. We couldn’t pay our suppliers because Don was hiving off all the money. So I went to the Chicago office of Don’s company, Advanced Vehicle Systems, and glanced at some papers on the company accountant’s desk before they were snatched away. I’d seen a company listed there called Margo Enterprises. Funnily enough, in the old radio series, The Shadow’s girlfriend was called Margo. So I said, ‘This wouldn’t be a company owned by Mrs Nichols, by any chance?’ That company had paid off the mortgage on the premises in Chicago. The accountant said, ‘Don’t tell Don you know. It’s meant to be a secret.’ ‘That’s fine,’ I said, ‘Just as long as I’m up to speed.’ Then I flew back to England and I said to Reesey, ‘We’re going to start an F1 team.’

“I went round all the suppliers and said, ‘I know Shadow owes you money. How much do you want for the debt?’ I bought up all of Shadow’s debts with my own money. Then I sued Shadow for payment. It was an aggressive tactic, but Nichols wasn’t playing straight with me. Don called Bernie [Ecclestone] and said, ‘Do you realise what Oliver is doing?’ Bernie called me, asked me what was going on. I told him I wanted to put Nichols into a position where he’d have to sell the team to me. Bernie understood that, and set up a meeting, him, me and Don, at the Brabham factory. Bernie and I sat there waiting, but Don never turned up. He’d changed his mind, he wasn’t going to sell.

“So I bought a factory at Milton Keynes, met all the people who were working at Shadow in a pub in Northampton, and said, ‘There’s a job down the road if you want it. Just give your mandatory notice period.’ And they all did, except Tony Southgate and two other people. Then Tony phoned me and said he’d decided to come too.”

Oliver and Pedro Rodriguez won Spa 1000kms with Porsche 917K – the Porsche pair got on well

Motorsport Images

At first the new team was to be called Ambrosio, after the Italian sponsor. Gunnar Nilsson was lined up as No 1 driver, although tragically his cancer meant he would never drive the car. By the official launch in January 1978 it was called Arrows, the name being derived from the key players: Ambrosio, Rees, Oliver, gearbox designer Dave Wass, and Southgate. Oliver found the factory on November 15, the first employees moved in on November 28, and work started on the first Arrows A1 on December 12. With virtually no break for Christmas, the car was presented to the press on January 20, and Patrese raced it in the Brazilian GP on January 29, finishing 10th despite a fuel feed problem. And, sensationally, it very nearly won its second race, the South African GP at Kyalami. With 15 laps to go Riccardo was well in the lead when the engine blew. By now Rolf Stommelen had been signed as the second driver, and Warsteiner beer was sponsoring the team.

“Meanwhile Don, give him credit for dogged effort, he’d hired people in and built a car to the design that Tony left behind. The Shadow DN09 looked identical to the Arrows FA1, because they’d both been designed by the same man. I was still pursuing Don for the debts I’d bought, and meanwhile he was accusing me of passing off and enticement. Then he sued me for breach of copyright.

“Bailiffs arrived at our factory with a court order to search the premises for evidence. They went through every desk and every filing cabinet, and found nothing incriminating. But stuffed down behind Tony’s desk was a roll of drawings, and they had Shadow written across the bottom. I don’t know why he’d brought them with him from Shadow, he didn’t need them, because of course he’d done new Arrows drawings. Tony said, ‘When I did those drawings I was an independent consultant at Shadow, I wasn’t an employee.’ I went to a copyright lawyer and he said, ‘You’re going to lose. Employee or consultant, Mr Southgate was in the pay of Shadow when he made those drawings. You’ll have to hand back all the copyright parts, and there will be damages.’ I said, ‘How long have I got?’ He said, ‘How long do you need?’ I said to Reesy, ‘How long to make a different car, design and build?’ Alan thought for a moment, and said, ‘I guess a couple of months.’ So I said to the lawyer, ‘See if you can keep the case going for a couple of months.’ We went back to Milton Keynes, and I told Tony to start designing another car.

“That was in April. Meanwhile Franco Ambrosio had got into trouble in Italy over his business dealings, and he ended up in jail, so no more money from him. In June Riccardo was second in the Swedish GP, beaten only by Niki Lauda in the Brabham fan car. And in July the court found against us. We had to hand over all the cars, except engines and gearboxes, and all the parts. But at the factory everybody had been working towards this verdict, and 10 days later we were at the Austrian Grand Prix with the new car. It had been designed, drawn and two cars built, all in 52 days. It was done in haste, and the A1 wasn’t as good as the FA1, but we didn’t miss a race.”

Jackie Oliver is a determined man. It took him three years to pay off the damages and costs of that court case, but Arrows raced on. There were isolated strong results: Patrese was second again at Long Beach in 1980, and at Imola in ’81, but he finally left for Brabham in ’82. “We had Jochen Mass, and Marc Surer – he stayed a long time – and Thierry Boutsen. We gave Gerhard Berger his first full F1 season: we were running BMW turbos by then. For 1987 I signed Derek Warwick and Eddie Cheever, and I had them for four seasons. Derek was the best driver I ever had. I really liked Michele Alboreto: very quick, very easy to get on with. Gianni Morbidelli was good, because he was a real trier. Christian Fittipaldi was all right, but not a patch on his uncle.

“I’d been after Neil Oatley to leave Beatrice and join us as a designer, but one day I had a phone call from somebody I’d never heard of. He said, ‘I’m an aerodynamicist at Beatrice, and Neil Oatley says you’re looking for a designer.’ That was Ross Brawn. What a brilliant guy. His Arrows A10B got us to fourth place in the constructors’ championship, our best result. In a technical environment, Ross was the best people manager I ever met. After Tom Walkinshaw hauled him away to do the Le Mans Jaguar we had Alan Jenkins, who was talented, but an awkward bugger. There were ring-binder marks in my office wall behind my head where he’d periodically throw his contract at me. In the end he was hired by Stewart.

“In 1989 I met Wataru Ohashi, the boss of a Japanese transport company called Footwork, who was really keen to get into F1. I sold him the team 100 per cent, but I kept operational control, and ownership of the factory which I leased to him. Wataru was a great guy, very straight. I wanted to go with the Cosworth HB, but Porsche wanted to get back into F1 with a normally aspirated engine, and Wataru liked the idea of Porsche power, so we signed a contract with them. I put an annex on the back of the contract setting out performance criteria for the engine in terms of weight, power output, fuel consumption and power curve. Porsche said, ‘That’s not necessary. The engine will meet all that anyway. We will make you the best engine in Formula 1.’ But I insisted on it being part of the contract. Just as well: the engine was a disaster. We had to throw it away and put the old Cosworth back in. It got a bit nasty, but I held Porsche to the contract and got our money back. We went to Mugen Honda engines for 1992. Then Wataru ran into money problems with the Japanese banks, and in 1995 I bought the company back from him.

“I had no sponsorship at all now, and I was pretty much backing Arrows myself. We painted pretty coloured squares on the cars so they didn’t look too naked, but I was spending £7 million a year of my own money keeping it going, and I told Bernie I was going to go bankrupt. It looked like he was going to lose two teams off the grid, because Ligier, which Tom Walkinshaw was now running, was in a bad way. So Bernie suggested we put a troubled Ligier and an impoverished Arrows together. In the end Ligier became Prost, but Tom came on board with me and we put together a five-year plan under which either I would stay or he would buy me out. Like most five-year plans, it didn’t last its term. I agreed to sell to Tom, and it took him 18 months to put the funds together to pay me.”

That deal left Jackie a very wealthy man, but it didn’t allow him to relax. He’s still a restless bundle of energy, director of four companies in the property and self-storage fields, and also a director of the BRDC. “I enjoy it. It keeps me in with racing people, and I like bringing a business perspective to it.” The negotiations over the British Grand Prix contract with Bernie Ecclestone were carried out by him and Silverstone Holdings chairman Neil England. “We were presented with something that was unaffordable. If the Donington project collapses and the Grand Prix comes back on the table, of course we’d be happy to take it, but it would still have to be commercially viable for us. And, in the time since Bernie took it away, the world economy has changed dramatically. So, if Donington fails, it doesn’t necessarily mean the Grand Prix would return to Silverstone.”

Jackie’s also a busy historic racer, doing around 15 meetings a year in the UK and Europe. He shares Shaun Lynn’s AC Cobra and Ford Galaxie, has done some events with Alan Mann’s Mustang, and also campaigns a Chevron B16 and a BMW 1800. And he’s still very quick. “It’s a joint venture with the cars’ owners. I don’t want to get involved in the preparation, I just love the racing. It’s getting back to my roots.”

His roots were those illicit late-night runs down the Southend Road, which led to a fine racing career. They also led to a Formula 1 team which stayed afloat in the piranha pool for 22 seasons: and that, for Jackie, remains his most satisfying achievement.