It was the last great Le Mans drive of a career spanning four decades. Bell Snr had to step up to the plate when his son, who had been driving the Harrods car together with Wallace since its debut in the fourth Global round, got spooked by the conditions during the night. “I remember Justin coming in and getting out after one hour when he was supposed to have done two,” says Derek. “His eyes were the size of saucers. He said, ‘Dad, I’ve never been so frightened in my life.’

Wallace, who anchored the Harrods assault with nearly 14 hours behind the wheel, still marvels at Bell Snr’s performance “The one thing I found out about Derek around that time,” says Wallace, who also finished second with the sportscar legend in that year’s Sebring 12 Hours, “was that if he has a chance of winning he steps up into another gear. He certainly drove very well.”

All was not well in the DPR camp, however. Pretty soon the car started to encounter clutch issues, a not altogether unexpected problem. The team had opted against using a new long-distance clutch offered by McLaren in favour of sticking with a modified version of what it knew, but this system had caused problems during qualifying.

The failure of the bearing on the release slider left DPR in a quandary. Engineer John Piper and Peter Stevens, the stylist responsible for the McLaren’s sleek outline but also a friend of Price’s who was helping out on the pitwall, spent much of Friday looking for a replacement. “It was a proprietary part that cost maybe £1.50, but there was an inherent weakness in it,” explains Piper. “Peter and I went around all the local bearing suppliers and engineering companies trying to find an alternative.”

Piper and Stevens were unsuccessful in their search, so they looked at either modifying the existing bearing or reverting to the standard clutch. Murray advised against the modification, while the parts necessary to facilitate the standard version weren’t available. “There was no clutch because the bearing had broken,” explains Wallace. “That gave us direct drive, which in a syncromesh box caused big problems. By the end of the race I was only using fifth and sixth because it was too risky to go across the gate.”

The Kokusai Kaihatso McLaren, which moved into the lead in the 22nd hour, survived its own late-race scare when an alarm came on after the last fuel stop, forcing a quick stop to re-pressurise the water system. Apart from that it was a faultless run. “That was always our aim,” says Lanzante. “Our strategy was to do our own thing and keep out of the pits.”

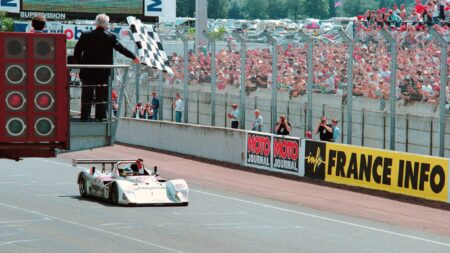

On a fully dry track, the Courage was closing fast in the final hours and the car even unlapped itself in the closing stages. The Harrods car ended up a further two laps behind in third, while the best of the GTC Motorsport McLarens finished fourth after team boss Ray Bellm had crashed in the wet. The Giroix Racing Team entry came home fifth after an early delay caused when a brand new starter motor failed.

It was a remarkable tale, and one that didn’t finish at four o’clock on Sunday afternoon. This surprise victory turned out to be a controversial one too. Not that anyone had a problem with a McLaren triumph — it was just that some within the British car maker’s camp took issue with which McLaren had won.

The Kokusai Kaihatso McLaren hadn’t been running in the Global GT series and was in fact the same hack that had completed the Magny-Cours test. The entry was made after a Japanese client of McLaren’s offered to sponsor a car. None of the existing teams took up the opportunity, and thus the decision was made to field F1 GTR chassis number 001R in the big race.

McLaren knew it couldn’t run the car from the factory — “It wouldn’t have been very nice to our customers,” says Hazell. Hence Lanzante, who was well known to McLaren Cars sales boss David Clark, was brought in. That didn’t stop the customers objecting. The handful of McLaren employees working on the car as mechanics rang alarm bells, as did the presence of Hazell and James Robinson, development engineer on the programme, in the Kokusai Kaihatso pit.

Exactly how ‘works’ the winning car was remains a matter of debate. Bellm famously cried foul, claiming that it was in his contract that McLaren wouldn’t run a factory car against its privateers. That wasn’t the case and he was forced to issue an apology to old friend Ron Dennis.

Today Bellm is less repentant: “When I discussed it with Frank Williams some time after, he said to me, ‘The ultimate test of whether it was a works entry is who employed the drivers, who owned the car and where does the trophy sit? The answer to all those questions is ‘McLaren’.’”

That may be the case, but Lanzante’s squad was certainly the smallest of the teams running an F1 GTR. What’s more, his relationship with the McLaren Cars bosses at the track was never easy. There are different versions of the story, but it is fact that Hazell and Robinson were banished from the winning car’s pit at one point during the race.

“We didn’t have anything different to any of the other teams,” says Lanzante. “There were only eight or nine of us. I even brought the cook into the team photograph at scrutineering to make us look bigger!”

And the ‘works’ allegation? “Bullshit!”

Thanks a million, Ron!

One million pounds. That’s how much Ron Dennis told Ray Bellm he wanted for a one-off racing version of the McLaren supercar. The pharmaceuticals magnate had just explained that he was going to go racing with the F1 he had on order whether his friend liked it or not. Unsurprisingly the offer was politely refused.

“When I said I couldn’t pay a million pounds for a racing car, Ron suggested I find some other people to help fund the development of a racing F1,” remembers Bellm. “He had already talked to Thomas Bscher (a German banker and historic racer) and I brought in Lindsay (Owen-Jones).”

At the same time. Dennis was being lobbied to go racing from within his road car division. A proposal had already been put together by Jeff Hazell, who was then running McLaren Cars’ composites department, after a fact-finding mission to Le Mans in 1993. A more modest plan got the green light after Hazell and Gordon Murray visited the May ’94 Dijon round of what would subsequently become known as the Global Endurance GT Series.

“We found a friendly series in which no one had really pushed the boat out in terms of preparation and development,” says Hazell. “We thought that without too much work we could get the car to a good level of competitiveness.”

The initial development budget was just £750,000, remembers Hazell: “That was all we had to do the design and development work, build a prototype and do the necessary testing before we had other cars coming down the line for customers.”

A production run of five cars, at £625,000 a pop, paid for this programme, according to McLaren Cars sales boss David Clark. He found the Fayed family of Harrods fame and gentleman racer Jean-Luc Maury-Laribière, and the F1 GTR was go, even before a sixth customer, French collector Paul Picard, produced his chequebook.

“Not much was done to the car for 1995,” explains Hazell. “We took all the rubber out of the suspension and the engine subframes, put a cage in, bolted on a rear wing and went racing.”

It added up to a tricky car to drive, remembers Harrods McLaren driver Wallace. “The BMW V12 was a gem, but it had a high centre of gravity and was forever trying to overtake you. It was the best road car ever, but it wasn’t a bona fide racer.