The statistics prove the point. In 1992, the season in which Peugeot claimed the final Sportscar World Championship crown with its lightweight 3.5-litre Group C machine, Philippe Alliot and Yannick Dalmas routinely pulled out qualifying times that were on a par with those set by the Lotuses and Benettons of the day. Yet that’s only part of the reason why the V10-engined 905 can lay claim to such a grandiose title.

It also has to do with the phenomenal pace of the Peugeot around Le Mans. Since the addition of the Mulsanne chicanes no-one has lapped faster that Alliot’s 3min 21.209sec pole of 1992. Yet even that doesn’t fully explain why Peugeot’s take on the final version of the Group C rule book can claim to be the ‘fastest ever’.

One does not have to be overly cynical to suggest that a formula sharing its engine rules with F1 was introduced by the sport’s governing body, then still known as FISA, to snare manufacturers into stepping up to the pinnacle of the sport. These 3.5-litre cars were in many ways grand prix cars with all-enveloping bodywork, but the 905, distinct from cars such as Jaguar‘s XJR-14 and the Toyota TS010, was like a grand prix machine in another way. It demanded to be driven like one — flat out every inch of the way. Even at Le Mans.

The fastest sportscar team. Ever.

The Peugeot’s tally of back-to-back Le Mans wins in 1992 and ‘93, world championships for both drivers and manufacturers, along with eight SWC victories from 16 starts makes for impressive reading. Especially when one considers that the Peugeot was a triumph of development over design. The 905 was a dog when it appeared at the end of 1990. A major rehash during the ’91 season transformed the André de Cortanze design into a real racing car capable of winning on the SWC trail, and then endless testing turned it into a phenomenal Le Mans machine. Even so, many involved in the Peugeot project concede that the Toyota was the better chassis.

The French manufacturer’s initial stab at Group C was a disaster. The problem, as Alliot has it, was that the car was “styled rather than designed”. He’s exaggerating, of course, but the racer clearly took its inspiration from the 1989 Oxia supercar concept. “It appeared to me that the stylists had been given a free hand,” says British engineer Tim Wright, who joined Peugeot Sport at the end of 1990 to help sort out the car. “I was amazed that this thing that looked so good could be so hopeless.”

Just how hopeless wasn’t apparent until the start of the 1991 season. The 905 was the first true 3.5-litre car to hit the racetrack, which meant that Peugeot’s only yardstick when it turned out for the end-of-season Montreal and Mexico City races in 1990 was the venerable Spice design. But when the TWR-Jaguar squad turned up the following year with its XJR-14, powered by Ford’s new HB F1 engine, Peugeot got a wake-up call. The 905 scored a maiden win at the 1991 SWC-opener at Suzuka, but the victory for Alliot and Mauro Baldi was a fortuitous one. Derek Warwick’s pole mark in the Jaguar was 2.5sec faster than the best Peugeot time, but trifling problems accounted for the two British cars in the race. On the team’s return to Peugeot Sport’s base in Vélizy near Paris, the leading players in the Jean Todt-managed squad gathered to figure out their next move. “We sat there and asked, ‘What can we do?’,” remembers Alliot “We may have won the race, but we had seen how uncompetitive the car was.”

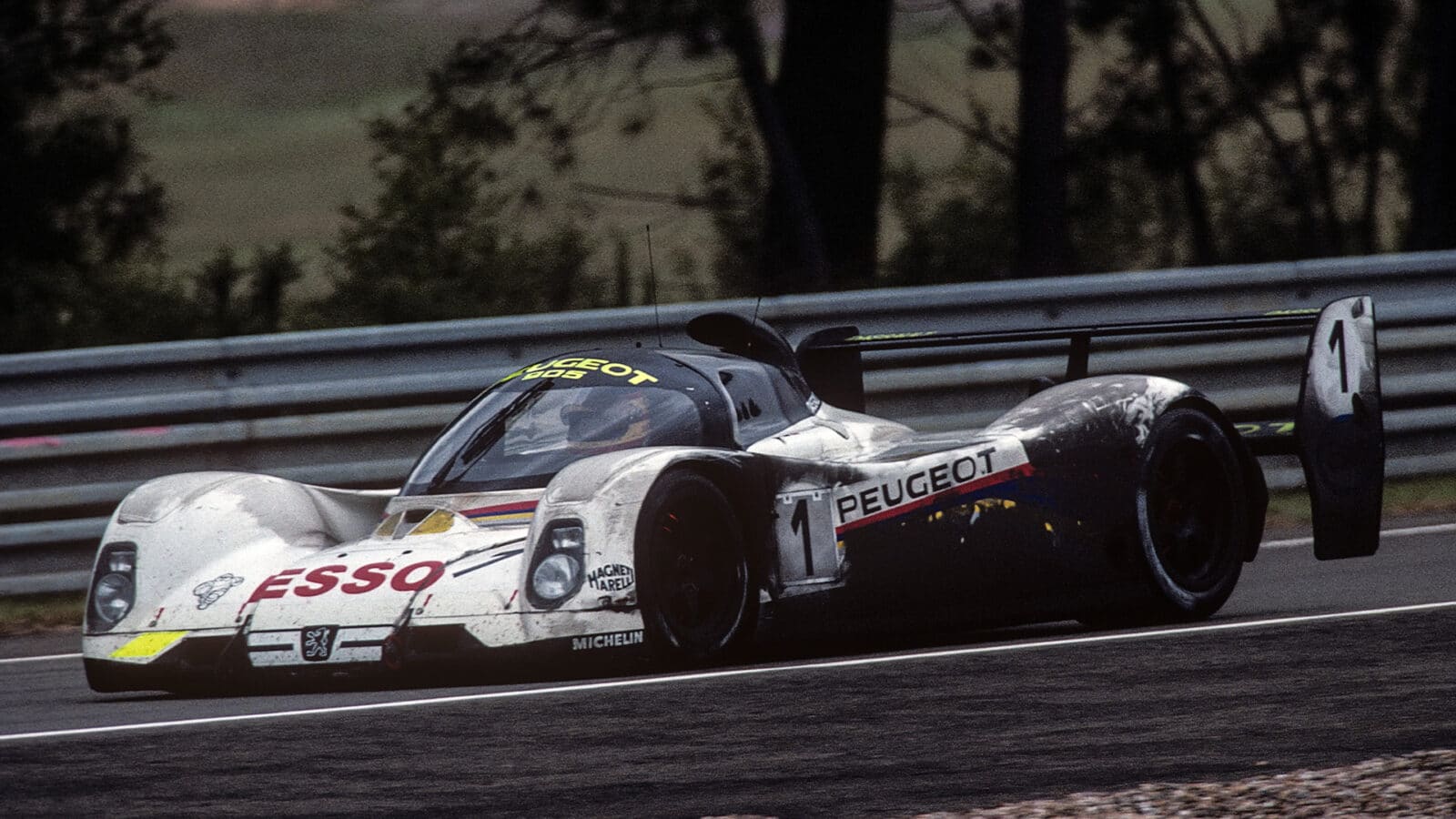

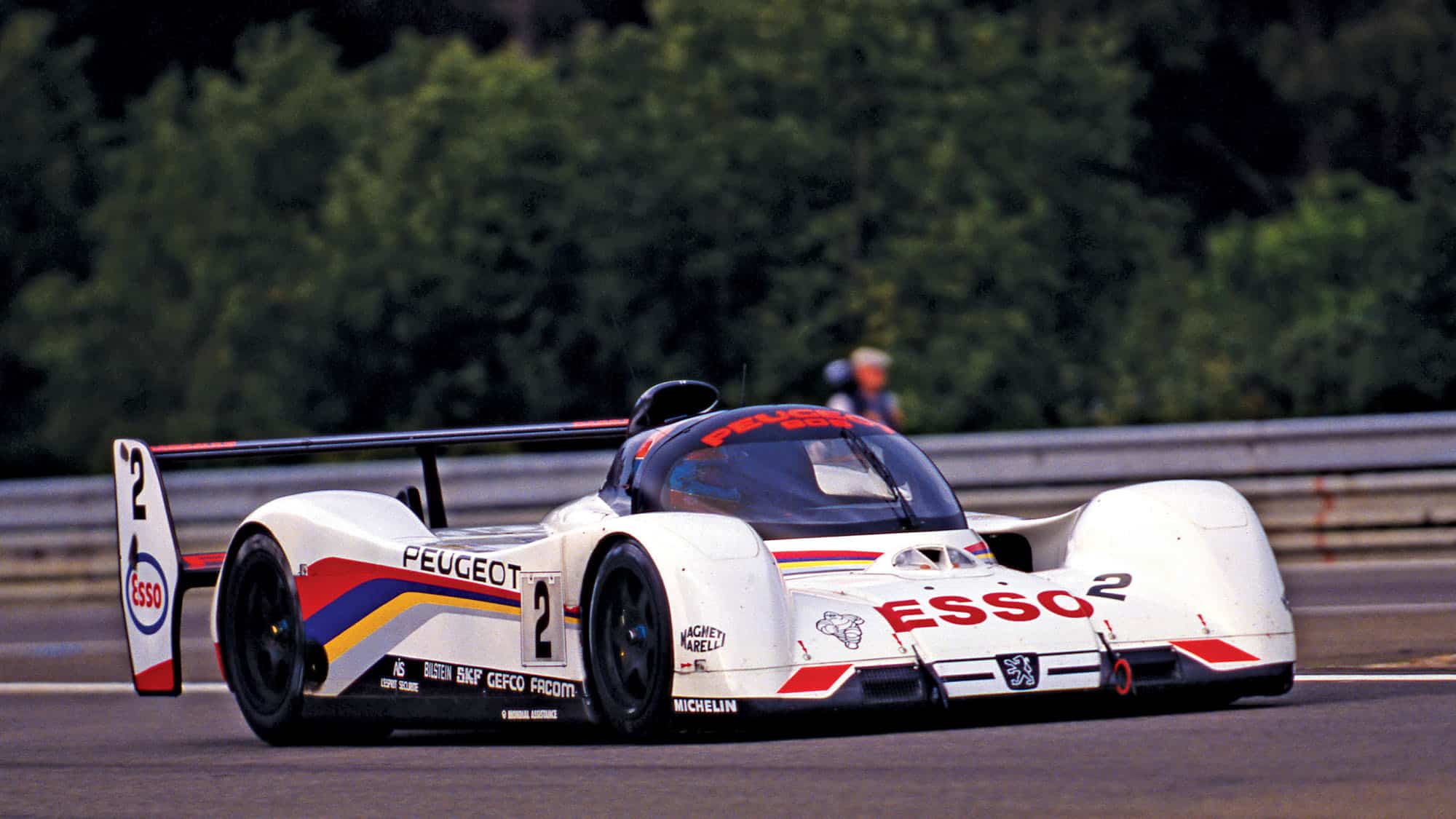

A “hopeless” Peugeot at Le Mans in 1991

Getty Images

The meeting set in motion a development programme that would turn the 905 from an also-ran into the class act of the SWC in the space of a few months. The redesign was almost entirely focused on its aerodynamics, although Peugeot also took the opportunity to switch from a heavy and unreliable self-built transmission to an Xtrac sequential ‘box. The target was to get the `Evo’ ready in time for the first SWC round after Le Mans, at the Nürburgring.

“We kept the same monocoque, engine and suspension, and changed the bodywork,” says Alliot. “When we came back and got the car totally sorted, we were 1.5sec quicker than the Jaguars.”