His ordeal lasted three laps before the 250F’s engine failed, but it gave him a taste of Formula 1. Over the next couple of years he was a regular contender in Maseratis, in his own car or those of other small teams.

“He was a nice guy,” recalls Phil Hill. “But he always lacked a certain something in terms of fire. He was always going to play it pretty safe.”

In 1957, Jo enjoyed a one-off outing for BRM at Modena, and his big break came towards the end of ’58 when they asked him to drive again, in the Italian GP. The gearbox failed, but next time out, at Morocco, he finished a promising fourth and was duly signed for a full season in ’59.

A works drive was a major boost to his status. He showed well in early races, but nobody anticipated what would happen at Zandvoort. The P25 was suited to the circuit; Jo put it on pole, and after gearbox problems afflicted the Coopers of Stirling Moss, Masten Gregory and Jack Brabham, he scored BRM’s first GP win.

He never repeated that form for BRM in 1959, though, and it was hard going against the Coopers in ’60, but he qualified third at Monaco and was fourth on the grid on three other occasions. Races brought little luck — the best he could manage was a couple of fifth places — and relations with BRM management were strained by the end of the year.

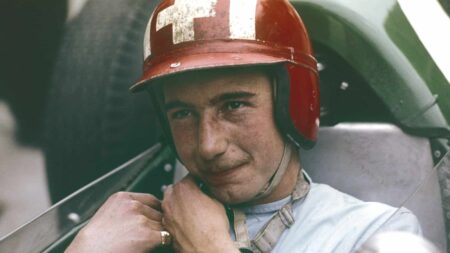

Bonnier en route to sole F1 win during the 1959 Dutch Grand Prix Zandvoort.

Grand Prix Photo

He had greater success with Porsche, winning the Targa Florio with Hans Herrmann (Jo would win again in 1963) and scoring several F2 victories. But high point of the year was his marriage to Marianne, an attractive Swedish teacher who helped soften his poker-faced image.

Porsche asked Jo to drive the new 1.5-litre F1 car in 1961, and some expected him to shine. He shared the pole time with three others at Aintree, but that was a rare peak as team-mate Dan Gurney quickly established his superiority. That year saw the birth of the GPDA, and Jo became its reluctant president, simply because the others asked him to do it. He would nevertheless become a prime mover in the campaign to improve safety standards worldwide.

On the track, the 1962 F1 season was disappointing — Gurney again outran Bonnier, although victory at Sebring provided some recompense. When Porsche pulled out, Jo teamed up with Rob Walker. Rocked by the recent deaths of Ricardo Rodriguez and Gary Hocking, Walker chose Bonnier for the unusual reason that he was a safe driver who was unlikely to get hurt. And Jo soon found an extra role as Rob’s business manager. His linguistic skills and position as GPDA boss proved to be very useful, as Walker notes in Michael Cooper-Evans’ book:

“He was shameless about using the clout this position conferred to obtain good starting money for the team — no doubt encouraged by the fact that, under our agreement, half of it would end up in his pocket.

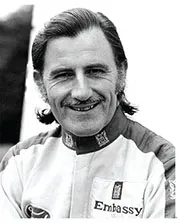

![Graham Hill Jo Bonnier 1960 Buenos Aires]](https://motorsportmagazine.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Graham-Hill-Jo-Bonnier-1960-Buenos-Aires-800x450.jpg)