In 1946 he became manager, consultant, chief tester and number one driver for Casitalia whose single-seaters were based on Fiat 1100s. They were good times, but in 1951 he joined Ferrari and finished third in the following year’s championship, behind team-mates Ascari and Farina. Later that year he and Luigi Chinetti shared the Ferrari 212 Inter that won the Carrera PanAmericana, storming over 10,000-feet-high passes, averaging almost 90mph for nearly 2000 miles. This made Taruffi a legend in Mexico. He was dubbed El Zorro Plateaclo The Silver Fox and taxi drivers pinned his photograph in their cabs, alongside the F Virgin of Guadalupe. He was then 45, but 1952 was his busiest season and his 16 races included a victory in the Swiss GP. He also masterminded Gilera’s capture of the world titles for riders and manufacturers. When I met Geoff Duke, 40 years later, he had nothing but praise for the shrewd, cool, deep-thinking Italian.

Two finishes from ten starts tell the story of 1953 with Lancia’s 2.9-litre V6 sports-racers. Finishing second in the Carrera Panamericana should have been the highlight – notes taken during a characteristically thorough recce enabled him to drive through fog at a 120mph but it turned to ashes when his team-mate, Felice Bonetto, was killed. Lancia got it right the next year when our man won the Targa Florio and Circuit of Sicily, which he regarded as an even tougher race. He won the Giro di Sicilia again in 1955, this time in a Ferrari, and also had two drives for Mercedes, finishing fourth in the British GP and second, hard on Fangio’s heels, at Monza. No wonder his Technique GiMotor Racing is one of the best books ever written on the subject.

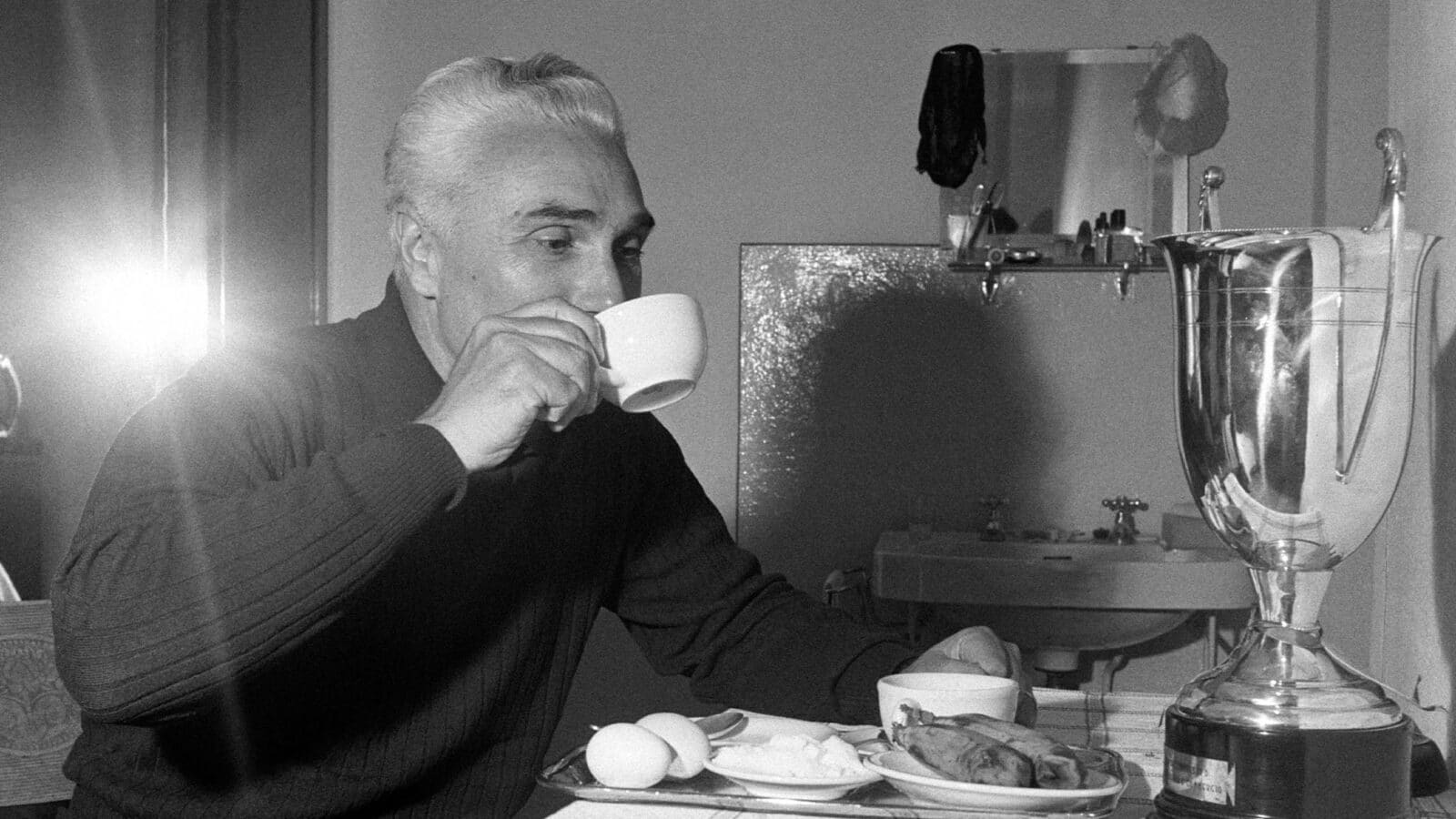

The Silver Fox promised his wife Isabella that he would retire when he won the Mille Miglia. Taruffi’s record went back to 1930, but victory had proved as elusive as dreams so often are. Isabella regarded the promise as her indomitable husband’s way of saying he would never call it a day.

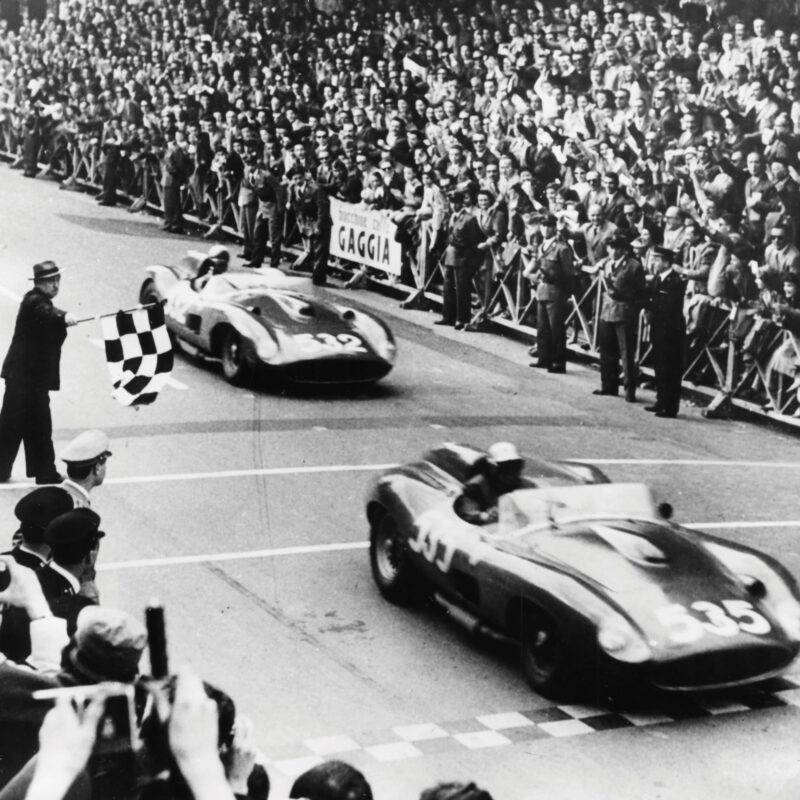

Taruffi leads von Trips across the line in a formation finish at ’57 Mille Miglia

Getty Images

In 1957 he was offered a Ferrari 315S with 370bhp to send it bellowing down the straights at to 175mph. He knew every inch of the course but went over it again before the race, memorising any feature that could help bring victory. Others carried a co-driver armed with pacenotes none more famous than this magazine’s Denis Jenkinson but the Silver Fox was also the lone wolf whose rivals included hard-charging youngsters such as Stirling Moss, Peter Collins and Wolfgang von Trips. There were problems. Well before Rome, the halfway mark, the transmission started making ugly noises, forcing Taruffi to use the higher gears as much as possible. Rain near Bologna demanded a ballet dancer’s touch on the throttle, because the Ferrari could spin its wheels at 125mph in top. But after ten hours 27 minutes and 47 seconds he crossed the line first, three minutes ahead of von Trips. The real Mille Miglia was never run again, because the swashbuckling Marquis de Portago had crashed, killing himself, his co-driver and several spectators.

Taruffi thanked Ferrari for the use of the car, pocketed his share of the prize money — “Less than I won this weekend,” he told me in 1976 — and retired after 34 years of racing and breaking records.

He had become involved in the quest for speed after taking a job as assistant to Carlo Gianini, the chief engineer of a company dedicated to building motor bikes and experimental aircraft. Together they designed the four-cylinder, 500cc Rondine. Carefully streamlined and ridden by Taruffi, it took the world’s flying mile and kilometre records at over 150mph in 1935. Two years later, hunching those broad shoulders into the aerodynamic bubble of a supercharged Gilera 500, he bagged 34 more records, including the flying mile at 169.05mph and the hour at 127mph, which remained unbroken until 1953.