Kling is from another generation. In terms of morals, he may as well be from another planet.

Fully 40 years after the accident which nearly cost him his life on the Nordschleife, he refuses to divulge the cause of the crash. The suspicion has always been that the Alfa Romeo Disco Volante sports car he was driving suffered steering failure. If it did, he’s not about to spill the beans. “I don’t speak ill of Mercedes,” he says, “so why should I say anything bad about Alfa. The people there were very good to me. They came and visited me in hospital every two weeks.”

There is not a hint of sarcasm in his voice.

Loyalty is a byword for Kling and it seems a strange concept, a throwback to an age of chivalry, if you like, in an era when most of us have been brought up on kiss and tell stories. Don’t expect Johnny Herbert and Benetton, Jean Alesi and Ferrari, or Mark Blundell and McLaren to give a glowing testament of each other after last season. But Kling resists speaking ill either of his former team or racing colleagues. For instance you get the impression that he didn’t really rate Juan-Manuel Fangio. He praises Stirling Moss as better able to adapt to a range of cars and hints that Fangio often benefited from other drivers set-up, as well as from the Silver Arrows’ team orders, but stops short of destroying a legend. “Those who are not alive any more should rest in peace,” he insists.

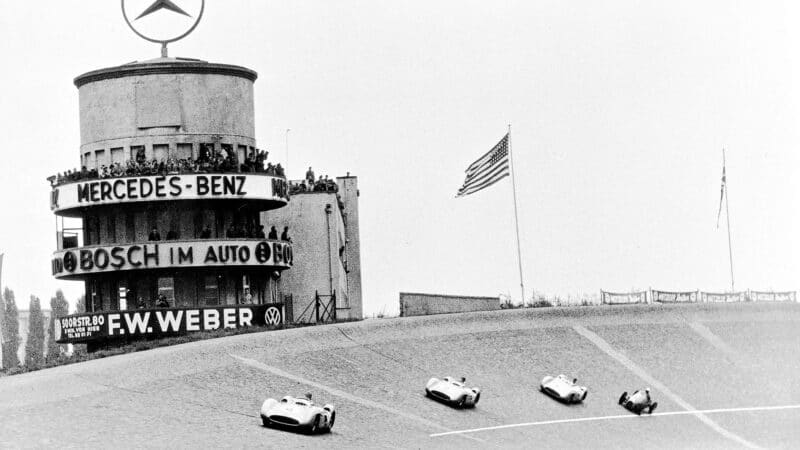

Banks at Avus illustrates the dangers of ’50s grand prix racing

Mercedes

Ironically, Kling himself was accused of breaking team orders by passing Fangio in the 1954 German GP. He maintains, however, that he never broke the faith, instead pointing out that he upped the pace because he knew a leaking fuel tank would require him to make an extra pit stop.

Aged 85, Kling is a Mercedes man. Always was. He began work there as a mechanic when he was 17 and with the exception of two races in an Alfa sports car and one in a Porsche for which the factory gave him permission – he drove only for the one marque.