1966 Monaco Grand Prix race report: Stewart finds winning formula

In spite of the new 3-litre engine formula being ushered in, BRM's Jackie Stewart shows that sometimes the old ones are the best

Stewart took his second career win on the streets of Monaco

Motorsport Images

Since the advent of the new Grand Prix Formula where the only interest seems to be for unsupercharged 3-litre engines, everyone had been waiting for the 1966 Monaco Grand Prix as it was felt that this race would really launch the new Grand Prix racing. Firms who were building new cars or new engines had the Monaco race as their target date and though Brabham, Cooper-Maserati and Ferrari got under way ahead of this schedule, BRM and McLaren made the dead-line with their new cars so that Monaco was full of technical interest as well as interesting motor racing. The only new projects that failed to reach the target date were the new Lotus with BRM H16-cylinder engine, and the Gurney-Weslake American “Eagle“.

McLaren entered himself and Amon with new McLaren cars but only managed to complete one car for himself, but this was a very creditable effort for a new team. Brabham had his 3-litre Repco-Brabham, Ferrari produced two 3-litre V12-cylinder cars, Cooper had two works Cooper-Maserati V12 cars and were supported by Bonnier and Ligier with similar cars, and BRM produced one new H16-cylinder car.

For the rest the entry was made up of modified 1965 cars, acting as stop-gaps until further new Grand Prix cars are finished. In view of the twisty nature of the Monaco circuit and its low average speed, the modified 1965 cars were well to the fore and some of them were really well suited to the circuit, in particular the two works Tasman Championship BRMs with 2-litre V8 engines, the works Lotus chassis R11 from last year, with a 2-litre V8 Coventry-Climax engine, and the Dino 246 Ferrari V6.

Qualifying

Practice began on Thursday afternoon and McLaren was among the first away as his car was brand new and untried, the Malite-sandwich monocoque chassis with 4-camshaft Indianapolis Ford V8 engine, reduced to 3-litres by means of shorter stroke crankshaft, not only looked very good, but sounded terrific. The engine carries a bit of a weight handicap, and the car appeared big for street racing, but undoubtedly has a good development life ahead of it and should be at home on the faster Grand Prix circuits. It was painted white with a green and silver stripe as a sop to Hollywood who are trying to make a Grand Prix film this season and who do not want a grid full of green cars, the dollars helped pay for engine development!

Graham Hill and Stewart drove the 2-litre BRM cars, the latter setting off at a cracking pace, and while they practised the BRM mechanics prepared the complicated, but exciting, H16-cylinder car for Hill to try.

Lotus had received their first 16-cylinder BRM engine a few days previously and had got it installed in their new chassis but it was too untried to enter for the race so Clark was alone in representing Team Lotus. The 2-litre V8 engine of his car was a big-bored, short-stroke 1965 Coventry-Climax engine with a new longer stroke crankshaft to squeeze another 500cc of capacity from the engine, and the increase in stroke was allowed for by thick aluminium plates between the heads and block, with the liners locating these plates. This was the car with which Spence won the South African Grand Prix and the engine was giving 245bhp with very little increase of weight over last year. The car’s potential round Monaco was not seen in the first practice as the crown-wheel and pinion gave out early on.

The Cooper team had the two cars they used at Silverstone, with Ginther driving the newer one, and the overheating problems had been traced to a badly made water filler neck on which the pressure cap was not seating properly. On this car the oil filter had been relocated alongside the engine, thus doing away with flexible pipes and long pipe runs, as it was on the cars of Bonnier and Ligier. As practice began a sprinkle of rain fell and clouds hung low under the mountains, but conditions did not deteriorate and the roads dried, so that Stewart was soon down to the existing lap record of 1min 31.7sec and by the end of the afternoon he had got one tenth of a second below this.

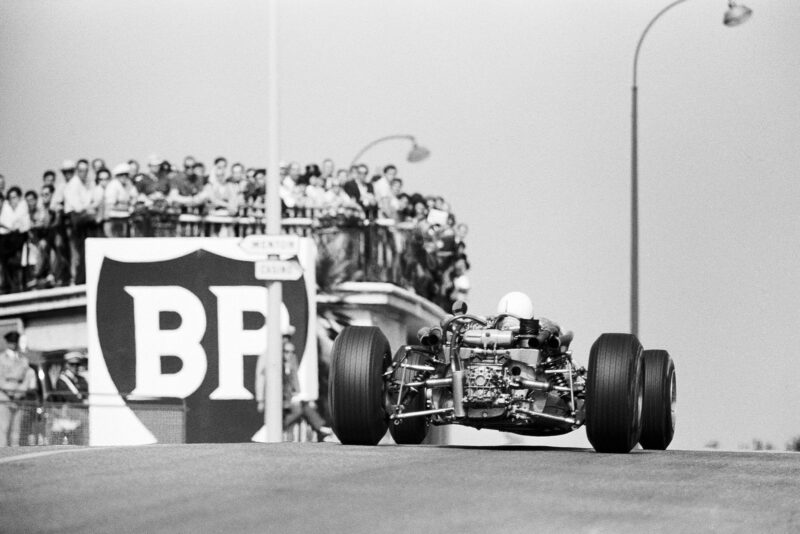

Ginther heads towards Massenet

Motorsport Images

There were no Ferraris out in this first session as the transporter had got held up on its way through Italy by heavy traffic, it being a National holiday, and the Brabham team-did not arrive in time either. The private-owners who practised were Spence, with the Parnell Lotus-BRM 2-litre V8, Siffert with Rob Walker’s 2-litre Brabham-BRM V8, as they were awaiting the arrival of their repaired V12 Maserati engine, after its Silverstone breakage, Bonnier with his red and white Cooper-Maserati V12 and Ligier with his bright blue Cooper-Maserati VI2.

The 16-cylinder BRM proved a little reluctant to start from cold, but after more batteries had been coupled into the system it burst into life and ran very sweetly, the noise being subdued until about 7,000rpm, after which it began to hurt the ear-drums. There was no intention to race the car, its appearance being solely in the nature of an initial public test-run and Hill did a few laps, his best being 1min 40.9sec. The engine was incredibly smooth and ran to 10,500rpm with no effort at all, and it was an achievement to get such a splendid piece of mechanism completed and functioning so early in the season.

The recent Fleet Street scaremongering stories about thefts delaying progress were the usual “comic-cuts” nonsense. In amongst the cars practising was the Lotus-Climax V8 1 1/2-litre that Baghetti “pranged” at Siracusa, suitably straightened it was entered under number 20 and Phil Hill drove it. On the front was a movie camera and he circulated around, trying not to get in the way, and took “action” shots. Certain members of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association opened their mouths to complain but before they could make a sound someone stuffed bundles of dollars into the mouths and that shut them up! The racing-car owners did not seem to be getting any compensation for risking their machinery in this comic-opera stuff.

On Friday morning practice was from about 8am to 9am, after the F3 racers had woken the whole town since 5:30am, and conditions were warm and dry. The Ferrari team arrived, as did the works Brabhams, and Anderson with his immaculate Brabham-Climax 2.75-litre. Surtees was driving the V12 Ferrari he had used at Silverstone and Bandini was in the Dino 246 Ferrari V6; the Brabham team of Brabham and Hulme were in their Silverstone cars, the former having a more powerful V8 Repco engine and the latter still with a 2.5-litre 4-cylinder Coventry-Climax engine.

The Coopers had removed the detachable front portion of the nose cowlings, in order to get more cooling air to the radiators, Siffert was still using the Brabham-BRM, as although his Maserati engine had arrived there was not time to prepare the car properly, and Clark’s Lotus had been repaired. The two works BRM 2-litres were going really well and Hill and Stewart were in great form, trying hard all round the circuit, as was Bandini with the V6 Ferrari.

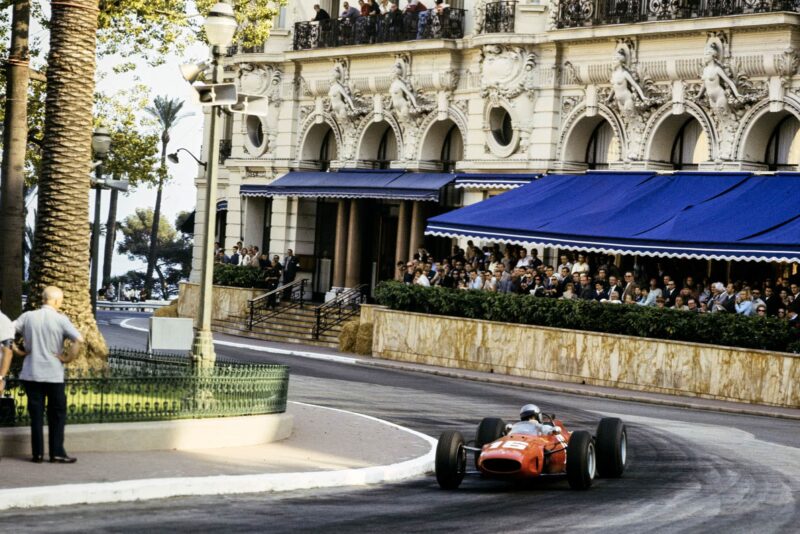

Lorenzo’s new 3-litre Ferrari was proving well-suited to Monaco

Motorsport Images

The 3-litre Ferrari was proving quite well suited to the twisty street circuit and Surtees was among the fastest. Graham Hill did a few more exploratory laps in the 16-cylinder BRM and McLaren was making steady improvements with his brand new car. As practice neared to its end there was a sudden flurry of high-pressure activity, and Clark began to make a real effort with the works Lotus, hurling it into corners at ridiculous speeds, and he came up with FTD in 1min 30.8sec, the only driver to break 1min 31sec.

Graham Hill and Bandini were not far behind and Hulme had been lapping in a most impressively smooth and unruffled manner to record 1min 31.8sec with the 4-cylinder Climax-powered Brabham. The final practice took place on Saturday afternoon under perfect conditions, with the sun shining but not too hot, and Ferrari had a brand new V12 car for Bandini to try, as well as the V6 car.

BRM had the 16-cylinder car at the pits, but did not run it as Hill was pretty busy keeping his good grid position. It was the last chance to get on the front of the grid and everyone was trying hard, for with a two-by-two starting grid no-one could afford to be too far back. The dreaded “camera-car” was still circulating and poor Phil Hill was wondering whether he had got too involved in something he couldn’t get out of.

Just how hard everyone was trying can be seen by reference to the final list of practice times in the accompanying table, the only ones not to improve being Rindt (Cooper-Maserati V12) and Brabham, whose new Repco engine had gone sick. The top runners were now down into the 1min 30sec bracket, and Clark felt convinced he could get below the 1 1/2-minute mark and just as practice drew to a close he went out for “the quick one” and made it by one-tenth of a second. 1min 29.9sec was recorded as he crossed the timing line and the chequered flag indicated the end of practice.

The last few minutes had been really furious and Surtees very nearly equalled Clark’s time, while Bandini, Stewart and Hill were not far off. Bondurant made his first appearance in Team Chamaco-Collect’s ex-works B.R.M. 2-litre V8 and Bonnier had a short try in the Parnell Lotus-Climax 4-cylinder to see if it was any quicker than his Cooper-Maserati V12 round the twisty circuit, and Anderson had been driving hard amongst the works cars and got himself a very good place on the grid.

Race

The field take the run up to Beau Rivage at the start.

Motorsport images

The race started at 3pm on Sunday in perfectly dry conditions under a hazy sky which was ideal, after a parade of old racing cars driven by various drivers of a past age. Lined up in pairs on the “dummy grid” the field of sixteen cars made a glorious sound which echoed amongst the blocks of apartments, and with everyone ready they moved forward to the proper grid. The sixteen cars surged forward when the flag fell, but one by one they overtook Jim Clark and Surtees led Stewart into the Saint Devote corner.

The Team Lotus car was jammed in first gear and by the time Clark got it out and into second gear the fifteen other runners had practically disappeared. Surtees led the race with the 3-litre Ferrari, but Stewart was right on his tail and the two of them quickly outpaced the rest of the field, which followed in the order Hill, Hulme, Rindt, Anderson, Bandini, McLaren, Spence, Siffert, Brabham, etc, with Clark right at the back, but starting to make up time now that he no longer had to use the low “starting gear” in his ZF gearbox. It looked as if Stewart was pushing Surtees, and the two of them were way out on their own and both trying very hard, for the rest of the runners were not hanging about, yet they were already out of touch at five laps.

“The sixteen cars surged forward when the flag fell, but one by one they overtook Jim Clark and Surtees led Stewart into the Saint Devote corner”

Clark had no trouble catching the tail-enders, and was lapping as fast as the leaders, and by ten laps he was in seventh place. Already Anderson had fallen out, Siffert was at the pits and McLaren was investigating an oil leak at the front of the car. Rindt had “chopped” his way past Hill and was third and Hulme also got past the number one BRM driver as the V8 engine was not working properly. As Surtees and Stewart braked heavily for the hairpin where the gasworks used to be, Rindt was just taking the Tabac corner onto the harbour promenade behind the pits, which gives a good idea of the pace the leaders were setting.

There was not much hope of Stewart getting his Tasman 2-litre BRM past the 1966 3-litre Ferrari, but he was not letting it have an easy time and was pressing hard. After they rounded the the hairpin on lap 13 Surtees felt something was wrong in the Ferrari rear axle and he waved Stewart past, and the young Scot soon came past the pits out on his own. Surtees toured round for another lap before stopping at the pits to investigate, and later did one more lap before he gave up with the self-locking differential broken.

This left Stewart out on his own, followed by Rindt, Hill and Bandini, the Italian closing rapidly to take third place. Hulme had dropped out with a broken drive shaft coupling and Brabham was out shortly afterwards with his new heavy-duty Hewland gearbox stuck in one gear. Clark was now in fifth place, in sight of the trio ahead of him, and whereas he had previously been lapping at the same speed as Surtees and not gaining on the leaders, he now began to gain ground because without the Ferrari V12 to goad him on Stewart’s lap times slowed fractionally.

Bonnier was the “red lamp” of the field, already lapped by Stewart, and he stopped at the pits as his Cooper-Maserati seemed to be suffering from fuel starvation. Rindt was being given a bad time by Bandini, and Ginther in the other works Cooper-Maserati was lying sixth just ahead of Spence in Parnell’s Lotus-BRM V8. By 20 laps Bondurant (BRM), Ligier (Cooper-Maserati) and Bonnier had all been lapped and at the same time Bandini snatched second place from Rindt, and these two and Graham Hill seemed locked together.

Slowly but surely Clark was gaining on them, and when he had Hill well and truly in his sights the BRM went a bit better and Hill overtook Rindt, so that Clark had the Cooper-Maserati in his sights. Spence and Ginther were lapped and though Stewart was still driving hard his position did not look unassailable, for Clark was gaining continuously. Not that he was gaining an easily measurable amount each lap, but whereas the gap had been 37sec it was now under 36sec, and after a bit it was nearer 35 than 36sec. He got past Rindt, whose Maserati engine began to show slight signs of the power dropping off, and by 45 laps Clark was lining himself up to have a go at passing Graham Hill’s BRM, which was not going to be easy.

Spence retired when a rear suspension link broke. At 50 laps, which was half-distance, Stewart was still ahead but Clark had narrowed the gap to 31sec, and was now patently being held back by Hill, who in turn could not get past Bandini, the three of them being very close. A remarkable sidelight was that at this point all four Cooper-Maseratis were still running, and the overall order was BRM V8, Ferrari V6, BRM V8, Lotus-Climax V8, Cooper-Maserati V12, all on the same lap.

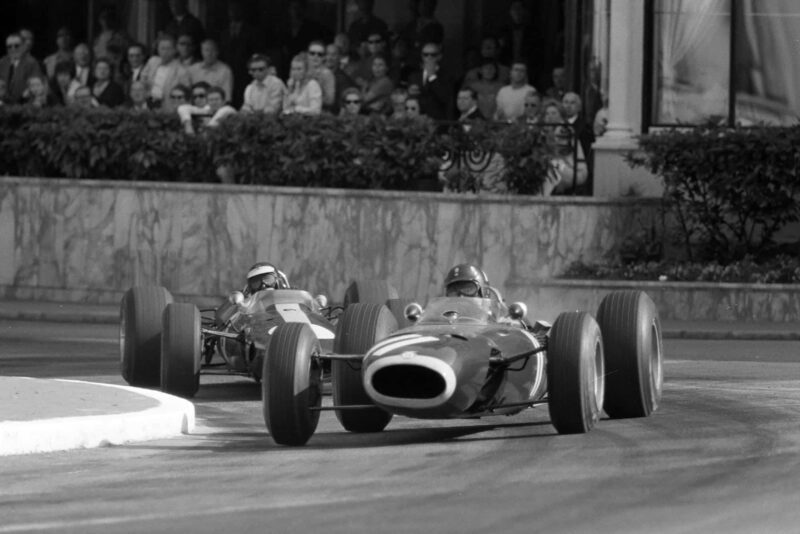

The race featured an intense battle between Hill and Clark

Motorsport Images

One lap down was the Cooper-Maserati V12 of Ginther, and a long way back came Bondurant (BRM V8), Bonnier and Ligier. By the time Clark was beginning to touch the rear of Hill’s BRM the gap to Stewart was down to 27sec, and Rindt went out with a broken engine. The gap remained constant for four laps until Clark decided it was “now-or-never” and forced his way by on the inside of the BRM as they both braked hard for Saint Devote corner. Hill could do nothing but move over and make room, and Clark was through.

At the end of that lap, the sixty-first, Clark was braking for the Gasworks hairpin when the left-rear hub carrier of his Lotus broke in two and he skated round the hairpin and retired, letting Hill back into third place. Either, from relief or tension Hill promptly spun at the first hairpin after the Casino square and stalled his engine, and lost a lot of time before he got going again, with a large dent under the nose of the car.

“Clark was braking for the Gasworks hairpin when the left-rear hub carrier of his Lotus broke in two and he skated round the hairpin”

Even with Clark out Stewart still could not relax, for Bandini was no less than 20 seconds behind and being urged on, added to which the BRM driver was having to lap the odd tail-ender and some of them he caught at awkward moments, where it was difficult to get by. Bonnier inadvertently held Stewart up for a while, and then Ginther had to be lapped again and the Cooper-Maserati takes up a lot of room. He “bullied” his way past Ginther as they approached the Tabac corner on the harbour front, and the Cooper-Maserati went all sideways trying to get out of the way of the forcing BRM.

Stewart was still lapping at around 1min 32.5sec or 1min 33sec and the gap between his BRM and the pursuing Ferrari was hovering around 18 seconds; not a small enough gap to be dangerous but small enough not to be able to relax. Ginther had stopped at the pits with a broken drive shaft, and had another one fitted, as had Ligier, the universal joints being a weak point, and the only other runners were Bondurant, who had had to stop for fuel, and Bonnier who was in and out of the pits.

On lap 82 Stewart lapped his team-mate and number one, and Bandini was a bare 12 seconds behind, trying all he knew, and setting up a new lap record on his ninetieth lap in 1min 29.8sec. That seemed to be his total effort, for the gap got no smaller and as the last laps ticked by the gap enlarged and Stewart was sure of victory. Ginther clanked to a stop on the promenade with another drive shaft broken, and Graham Hill had backed off and was touring round in a secure third place, with Bondurant fourth, having driven a very smooth and reliable race. Stewart had really had to work for his victory and in consequence he had set up a record average speed for the 100 laps of the classic Monte Carlo circuit.

Stewart heads the track on his victory parade

Motorsport Images

Formula 3 Race

During the meeting a very large and truly International entry of Formula Three drivers, mostly with Ford-engined cars, contested the miniature Grand Prix on the same circuit. Practice sorted the entry out into two manageable heats, and on Saturday afternoon these raced for 16 laps, the fastest eleven in each heat going into the 24-lap Final.

In Heat 1 Jean-Pierre Beltoise in a works Matra led with very little trouble, from Ahrens in a Brabham, these two leading many noted British entries such as Gethin, Pike and Beckwith.

Heat 2 saw a very good scrap between Cardwell (Ron Harris Lotus 41), Irwin (Chequered Flag Brabham), Courage (Lucas Lotus 41), Williams (de Sanctis) and Bondurant (Brabham with DAF transmission). After a close opening lap Irwin got the lead and drew away to a sound win. Twenty-two cars lined up for the Final and it was Courage who took the lead, from Irwin, Williams, Beltoise Cardwell, Ahrens, Bondurant and Jaussaud, but on lap three Courage hit the wall of the Tabac corner, which bent the Lotus front-suspension very badly. Luckily he bounced off the wall and kept going or there might have been a big pile up, but as it was Irwin and Williams had to dodge the bouncing car and this let Beltoise snatch the lead.

Beltoise and Irwin then outpaced the rest of the field, never more than a few lengths apart, the Brabham driver handicapped by having an inoperative clutch, and Monaco is no place for clutchless gearchanges. Round and round the two of them went, Irwin hoping that the young French driver would make a mistake, but he did not and came home to a well-deserved and popular victory a few lengths ahead of the Chequered Flag Team’s Brabham.

Monaco Murmurs

- In practice those hardened Dunlop users Ferrari and BRM experimented with the opposition’s tyres, Surtees trying Firestone and Graham Hill trying Goodyear.

- The 12-cylinder Ferraris were using ventilated brake discs, and at one point in practice the pads on one rear brake were actually in flames when Surtees stopped.

- Cooper were using cut-down windscreens to make life easier for the drivers, and Mclaren cut the nose of his car away to improve the cooling.

- The works Brabhams were using a combination of Hardy Spicer mechanical universal joint and “bungy doughnut” drive on the inner ends of their driveshafts.

- After the practice trouble the mechanics had to put the Silverstone engine back in Brahham’s car.

- Surtees raced on 15-in, rear tyres, with knock-off hubs as used on the 330P3 Prototype Ferrari.

- The second and brand new V12 Ferrari that Bandini tried in practice was similarly equipped. Although it did not complete in the race, the H16-cylinder 3-litre BRM made a good impression.