1958 Monaco Grand Prix race report: Trintignant makes it two in a row for Rob Walker Racing

Maurice Trintignant profits from others' unreliability to take the second win of his career and Rob Walker's second of the season; Stirling Moss, Mike Hawthorn and Tony Brooks all retire whilst leading

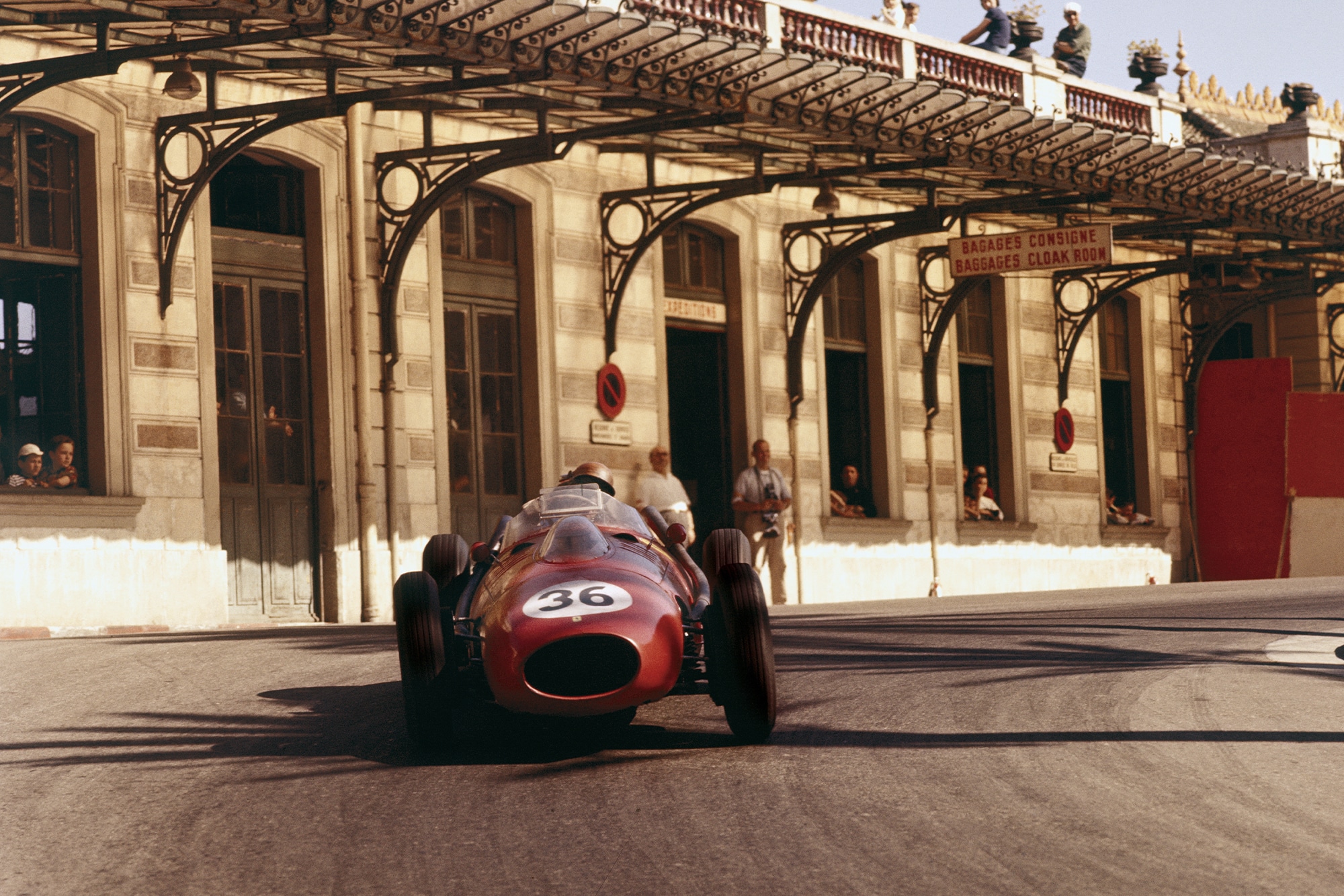

Wolfgang Von Trips takes on the Loews hairpin

Motorsport Images

THE organising committee of the Automobile Club of Monaco deserve full marks for not pandering to the present-day ideas of the FIA in turning Grand Prix races into “sprint-type” events, for they kept the XVI Monaco GP to a traditional full-length GP of 100 laps of the tiny, narrow, 3.145km street circuit. On the other hand they overdid their enthusiasm in inviting 29 entries to compete when the maximum permitted for the starting grid was 16.

Selection was made by practice times, the fastest 16 being considered as qualifiers. When it is borne in mind that 14 factory cars entered, plus the professional equipes of Rob Walker and Gugliemeno Dei, there was little hope for any truly “independent” driver. Although only 25 entries appeared for practice, BRM being one factory entry short, it still meant that the also-rans were wasting their time and wearing their cars out to no purpose.

Peter Collins on his way to third in the Ferrari Dino 246

Motorsport Images

However, it did provide them with an opportunity to learn the Monaco circuit and gain a lot of experience, but it was at the expense of cluttering-up the road with a lot of slow traffic for the works drivers and Monte Carlo is not a circuit for that sort of thing. It would have been far more intelligent to have invited two or three extra “independent” runners of known quality, over and above the 14 factory cars, rather than 15 for then they would have almost certainly got on the starting grid. Campbell did not arrive with his Maserati; Ecclestone sent only one Connaught, which Emery and Kessler had to share; BRM forfeited Flockhart’s entry, though the Scot took over Walker’s second and older Cooper; and a Maserati entry, reserved in case Fangio felt like coming, was, in fact, not used.

First practice, in hot sunshine on Thursday afternoon, saw Behra in a 1958 BRM, Schell in a 1957 car and a brand new 1958 car as reserve, which Schell eventually used in the race; Salvadori and Brabham had 1,960cc Coopers, the 2.2-litre-engined car standing by as reserve; Trintignant and Flockhart were driving for Rob Walker; Allison and Hill were in the official Lotus cars; Moss, Brooks and Lewis-Evans were out for Vanwall; and Musso, Collins, Hawthorn and von Trips for the Scuderia Ferrari. In Maseratis were Godia, Bonnier, Miss de Filippis and Testut, and Gerini and Taramazzo for the Centro-Sud team, and to complete the list, the lone Connaught.

Qualifying

At 3pm practice started and everyone went quietly round, feeling their way along, the newcomers trying to remember the many corners of the twisty circuit and getting used to the darkness of the tunnel on the sea-front, while the “old hands” weighed up the situation in general. Apart from a widening of the chicane leading onto the harbour front the circuit was unchanged and practice opened with laps around 1min 55sec for the faster cars, until there was a big surprise when Behra livened things up with the BRM.

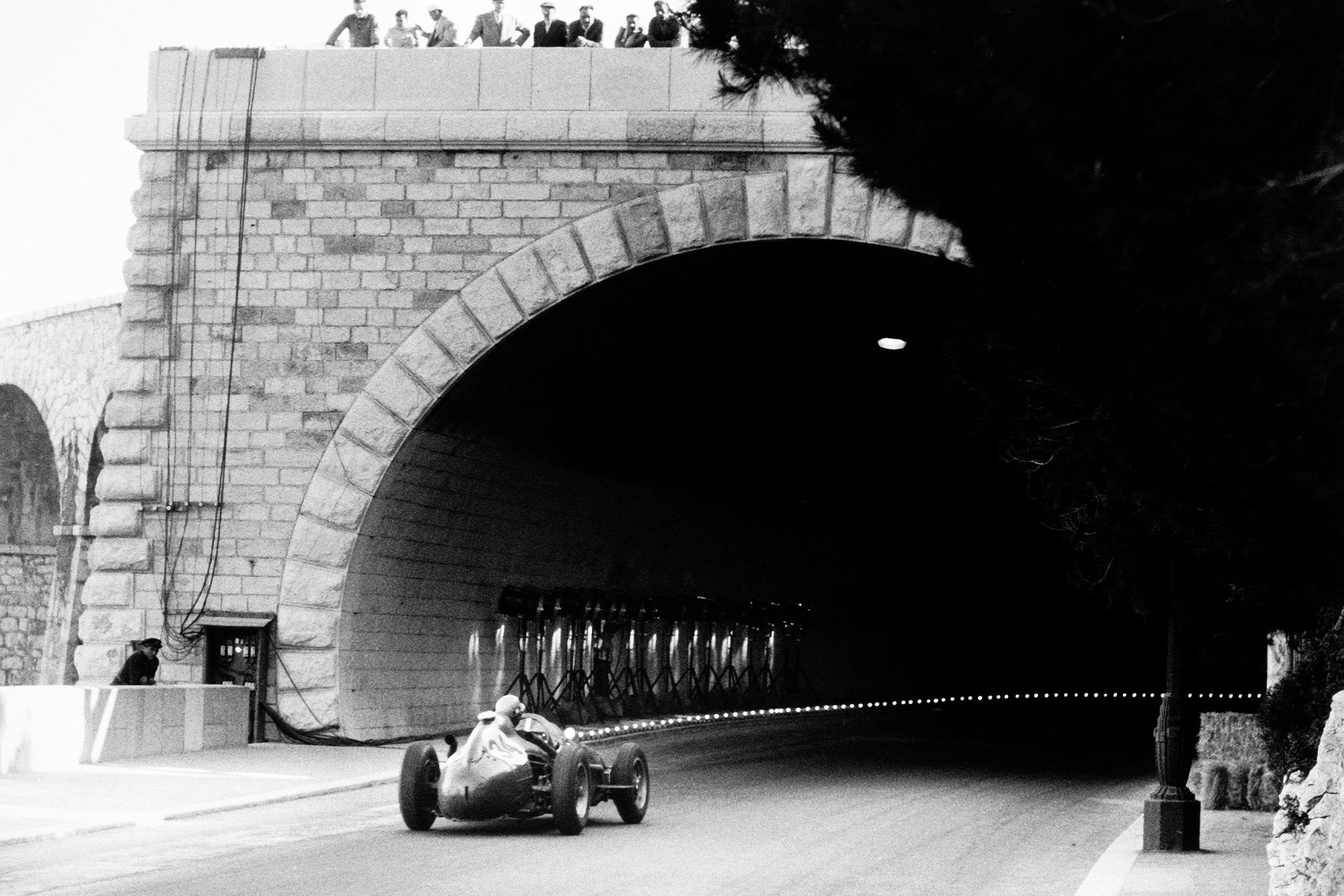

Luigi Musso heads into the tunnel

Motorsport Images

Once having got attuned to the circuit he began to set the pace and kept it up, so that everyone else had the BRM times as an objective. Ferraris were not too happy, their front suspension seeming a bit hard and they were geared low, while Vanwalls were making their first outing for 1958 and working up to things gradually. Moss was not happy with his car, the steering and front brakes not being perfect, and he borrowed the second car from Brooks, but both drivers were down on the times Behra was doing, the BRM getting down into the 1min 42 sec bracket.

Hawthorn was quickest of the Ferraris, while Schell was backing up Behra quite well, using the old BRM. Of the “tiddlers” or miniature Grand Prix cars, Allison was in trouble with his Lotus, a head gasket blowing, while Hill was having his first taste of high-pressure Continental dicing and finding the Lotus brakes a bit tricky on the polished road surfaces. The Coopers were coming well up to expectations, not only the works cars but also Trintignant in Walker’s 1958 car, though Flockhart in the 1957 Walker car was hampered by unsuitable gear ratios, the old-type gearbox not allowing such a good choice.

“The Ferrari engineers shrugged and sent Collins out again, seemingly deciding that, if it flew apart…well it would be too bad”

Collins came in complaining of a bad engine vibration but after putting a finger on the steering column the Ferrari engineers shrugged and sent him out again, seemingly deciding that, if it flew apart…well it would be too bad; however, it did not; it just went on vibrating. Apart from the necessity of getting in the best sixteen times there was also the added attraction of a prize of 100,000 francs for the fastest lap, and these two encouragements, together with circuit conditions being excellent, the pace got hotter and hotter as the afternoon wore on.

Behra was still leading the split-second battle and he finished his efforts with 1min 40.8sec, a vast improvement over the race lap record set up in 1955 by Fangio at 1min 42.4sec, and improving on the best ever in practice for previous years, which was 1min 42.7sec. However, just before the end of practice Brooks went out again and equalled Behra’s time, while Trintignant had been trying really hard and he beat both works Coopers, making third best time with 1min 42.2sec, while Moss was next with 1min 42.4sec, using Brooks’ car. The “independents” had all been thrashing round but to little avail, only Trintignant, Bonnier, Godia and Emery getting in amongst the factory drivers and the best sixteen on this first outing, a time of 1min 50sec being the slowest permitted.

Salvadori and Brabham talk before the race

Motorsport Images

On Friday morning practice began at the unsavoury hour of 5:45am and everyone except the BRM team was out, the Bourne equipe quite justifiably resting on their laurels. The sun was shining but there was an ominous breeze blowing and clouds were gathering over the mountains behind the town. With a rush practically all the cars set off to practice and there was so much traffic about that there was little hope of going fast, and almost as if by mutual agreement all the fast boys suddenly stopped, with the result that only one or two “independents” were left circulating.

However, after this initial enthusiasm the factory cars began going off again in ones and twos, and soon practice got into a normal and reasonable stride. Salvadori and Brabham had drawn lots for the 2.2-litre car and the Australian driver had won, and both they and Trintignant were really driving hard. All four Ferraris now had the latest type of Perspex bubble over their carburetters and Hawthorn had thrown away his Perspex windscreen and was using only a small rectangular aero-screen, while von Trips was still awaiting his larger engine, having to make do with a 2-litre unit in the meantime.

All was not well in the Vanwall team, for the Moss car had something obscurely wrong with the front suspension and steering, and though it all looked quite normal it was behaving most peculiarly on corners. Moss could not get below 1min 45sec so he came in to try another car, but for some strange reason the Vanwall team manager would not let his Number 1 driver take the Brooks car, offering only the third team car as an alternative. This quite rightly upset Moss and he did no more practice in the Vanwalls, sitting on the pit counter and watching everyone else improving on their times, until he went and saw his “other boss,” Rob Walker, and did a few laps in the old Cooper. Meanwhile Brooks and Lewis-Evans were standing by waiting to be told what to do.

Towards 8am conditions became perfect for fast motoring for the gathering clouds had obscured the sun and a breeze was keeping everything nice and cool. Brooks went out and put in a series of very fast laps, ending up with 1min 40.7sec, and found everything about his car very much to his liking, so he then tried the Moss car and did three laps at nearly 1min 43sec but did not try too hard because of the strangeness about the front end. A check on the fastest driver showed that Lewis-Evans was not well placed, with his time of 1min 43.5sec, so he was asked if he’d like to try and improve on it. He went off and after two warming-up laps he did 1min 42.7sec, and then 1min 41.8sec; then he stopped, saying, like Brooks, “Thank you, everything is very nice.”

Collins qualified in 9th position

Motorsport Images

In the Cooper camp everyone was very happy and the two works drivers were ideally suited to their cars and to the circuit, and by the end of practice they had both recorded the remarkable time of 1min 41.0sec, while Trintignant was only a tenth of a second behind them, and they had all left the Lotus team far behind. The boys from Hornsey were most unhappy for though Allison was beginning to learn his way round he had to stop as a pipe-line broke on the clutch actuation. Hill was still not happy with his braking and he eventually hit a kerb over by the Station hairpin; although he only nudged it,” he broke the right front wheel, bent the wishbone and spring unit, destroyed the king-post, twisted the chassis and tore a piece out of the bottom frame member, so Team Lotus spent the rest of the day rebuilding the car.

“After equalling his best time Brooks then beat it by nearly a whole second and clocked an incredible 1min 39.8sec, which must have made the BRM team turn uneasily in their beds”

The poor private owners were really getting nowhere, even though some of them were trying very hard, and of the Maserati group only Scarlatti and Bonnier managed to scrape into the first sixteen, the latter being last with a time of 1min 45 sec, an excellent time but indicative of closeness of qualifying requirements. The Italian girl driver had done a terrific 1min 48.8 sec, beating nine more men, but she could not get into the starting list, while the Centro-Sud team, with three cars and Gould to help them out, were not in the running, their regular driver Masten Gregory being with Ecurie Ecosse at Spa. The two sports Oscas driven by Cabianca and Piotti were really wasting their time, and the lone Monegasque entry of Testut with his Maserati could not qualify even though Chiron went round in it until it was nearly worn out.

Just as practice was finishing at 8:15am Brooks went out again in his own car and, starting with a lap in 1min 41.3sec, he did four laps and after equalling his best time he then beat it by nearly a whole second and clocked an incredible 1min 39.8sec, to make undisputed fastest time, which must have made the BRM team turn uneasily in their beds. The first practice day was decidedly a BRM day, the second a Vanwall day, and on both days the little Coopers were chasing them both very hard.

MotorSport’s Denis Jenkinson chats with Lotus team boss Colin Chapman

Motorsport Images

There was one more practice, this being on Saturday afternoon, and in the meantime the Vanwall mechanics had done a big shuffle with their “kits of parts” and assembled another car for Moss, and fitted the Lewis-Evans car with a set of alloy wheels, while Ferrari had put the spare 2½-litre Dino engine into von Trips car. The previous night there had been a lot of rain and although the town was dry and sunny the circuit was not in such perfect condition as the day before and the hot sun was not the best thing for carburation. Everyone was out again, even the BRMs, and the object of the afternoon was perfectly clear.

A minimum time of 1min 45sec was the aim of the slower cars and an improved position on the starting grid the aim of the faster cars and drivers. Due to the circuit conditions the stars were making no improvements, apart from Moss, who now had a car that went properly and he soon did 1min 45 sec, but then a Maserati blew up and showered oil everywhere and there was little hope of improvement for some while. Coopers were so happy that they did not bring all their cars out, spending the time playing with the, spare one. BRM had all three cars out, but Behra was in trouble for a time with the Weber carburetters and Schell could not decide whether he preferred the new car to the old one.

Von Trips was finding the extra weight of the bigger engine and the added 50bhp making a big difference to the handling of his car. After the oil had been cleared away Brooks went out in his Vanwall, lapping very consistently, and then Moss joined in and slowly but surely the number 1 driver gained on his team-mate, until the two Vanwalls were nose to tail, and then the tension subsided as Brooks lifted his foot and let Moss go by. It was a fine sight to see the two green cars running so close together but a little worrying and unnecessary in practice, though the result was that Moss clocked a time of 1min 42.3sec. When practice finished the final list of times showed that none of the previous list of sixteen fastest had been knocked out and, apart front the improvement made by Moss, there was little change.

Race

A frenzied start to the race

Motorsport Images

On Sunday afternoon, in brilliant sunshine the sixteen fastest from practice lined up on the starting grid while the rulers of the little Principality of Monaco indulged in some pleasant pageantry. The line-up showed the remarkable sight of Vanwall, BRM and Cooper in the front row, more Coopers in row two, and not until row three was there a splash of red, and even the most ardent Italian enthusiast must have felt that perhaps the British were dominating the scene, even if only by sheer weight of numbers, for of the sixteen fastest cars ten were British. The order was:

- Brooks (Vanwall) 1min 39.8sec

- Behra (BRM) 1min 40.8sec

- Brabham (Cooper) 1min 41.0 sec

- Salvadori (Cooper) 1min 41.0sec

- Trintignant (Cooper) 1min 41.1sec

- Hawthorn (Ferrari) 1min 41.5sec

- Lewis-Evans (Vanwall) 1min 41.8sec

- Moss (Vanwall) 1min 42.3sec

- Collins (Ferrari) 1min 42.4sec

- Musso (Ferrari) 1min 42.6sec

- Schell (BRM) 1min 43.8sec

- Von Trips (Ferrari) 1min 44.3sec

- Allison (Lotus) 1min 44.6 sec

- Scarlatti (Maserati) 1min 44.7sec

- Hill (Lotus) 1min 45.0sec

- Bonnier (Maserati) 1min 45.0sec

It is worth noting that a mere 5.2sec, separated the fastest from the slowest, so that by a process of elimination the XVI Monaco Grand Prix had a remarkable collection of cars and drivers straining every nerve as the flag was raised. Everyone got away to a splendid start and roared off towards the Gasworks hairpin, with Salvadori actually arriving in the lead but going too fast to take a normal line and he swung wide, letting Behra, Brooks and Brabham through on the inside.

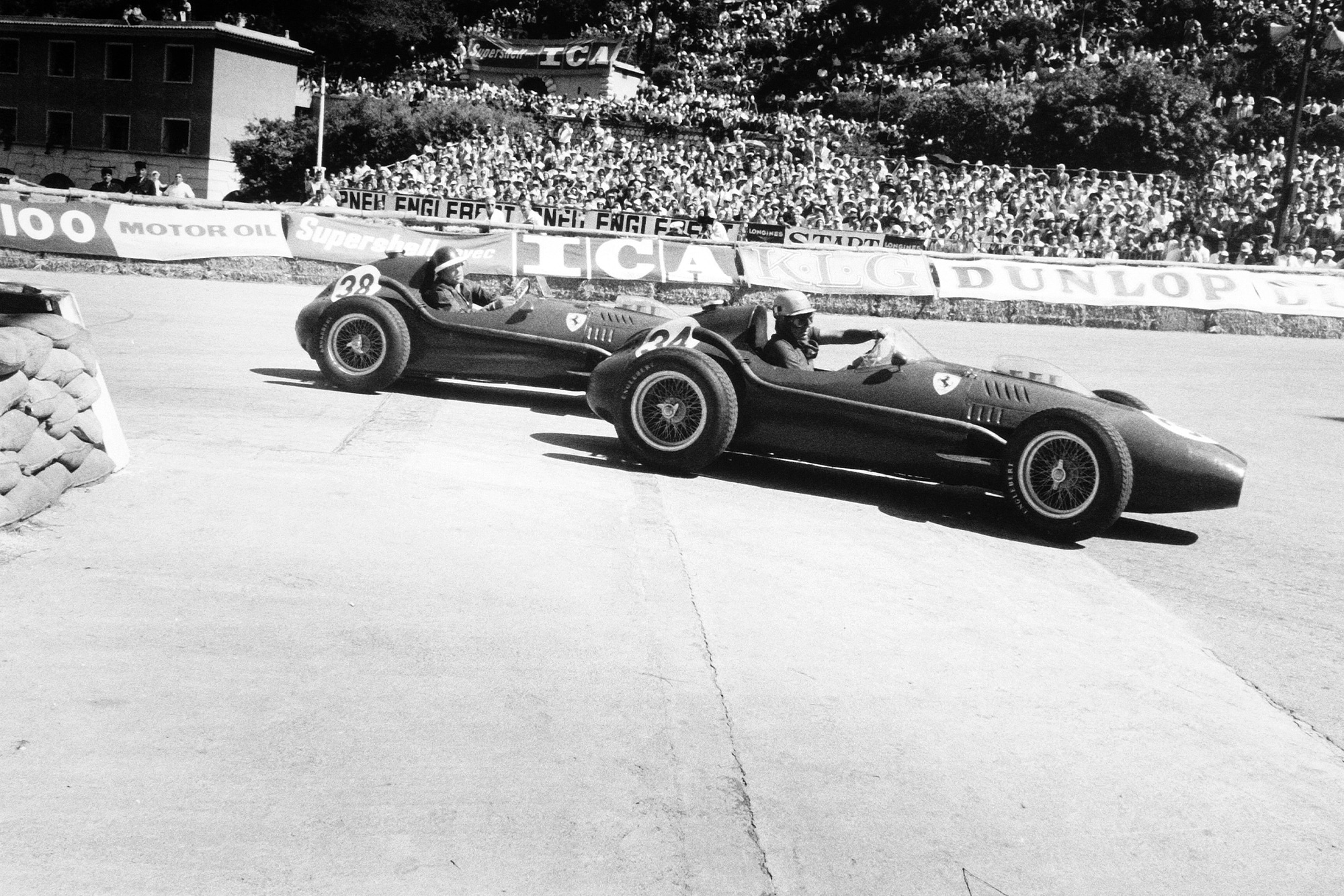

Hawthorn and Musso vie for position

Motorsport Images

There was a bit of a scuffle and some bumping and boring, and when it was all over Salvadori found he had a loose steering-arm on one hub and limped round to the pits. The locating bolts had stretched in the bumping and he lost three laps while things were sorted out. Meanwhile, Behra was away in the lead, followed by Brooks, Brabham, Moss, Trintignant, Lewis-Evans, Hawthorn, Musso, Schell, Collins and von Trips, the two Lotuses running along at the back of the field with the two Maseratis.

Behra and Brooks began to draw away on their own but behind them Hawthorn was having a real go after the dust of the opening lap had settled and he passed Lewis-Evans and then Trintignant. By the fifth lap he was on the tail of Moss’ Vanwall and on the eighth lap he got by and set off after the BRM and Vanwall ahead, gaining ground visibly. Although Behra was not being troubled by Brooks the gap between them was pretty constant and Hawthorn was getting ever closer, so that by 10 laps he had the Vanwall well in his sights and had left Moss someway back. Farther back, Trintignant was worrying Brabham, while Lewis-Evans was slowing, to come into the pits on lap 12 and retire with overheating, and then Brabham began to lose ground, stopping at the pits on lap 22 with a loose antiroll bar mounting, the time taken to effect a repair dropping him back to next to last position ahead of his team-mate Salvadori.

Hawthorn eventually got by Brooks on lap 18 and on the next lap Moss also passed Brooks, so it seemed something was not right and, sure enough, Brooks stopped on the hill up from Ste Devote corner and switched off when his engine made a horrid noise. Removing the bonnet he discovered that a sparking plug had come unscrewed and was lying on the cylinder head still attached to its lead. Alas, it was too late, he had no hope of restarting uphill, so reluctantly had to retire; less than quarter-distance and two Vanwalls already out, leaving Moss their only hope. He responded magnificently and began to gain on Hawthorn, who was in turn gaining on Behra.

Behra started second but couldn’t make the finish

Motorsport Images

On lap 27, after a splendid try, the BRM drew into the pits with the brakes feeling peculiar, and after one more lap Behra retired rather than risk complete brake failure; naturally, this let Hawthorn into the lead, but Moss was not going to sit back and look at the Ferrari’s tail and he began to overhaul Hawthorn. All this interest at the head of the field tended to overshadow the rest of the runners, but Trintignant was holding on to the leading pace and keeping in front of Musso, Collins and von Trips, who were following in that order.

Schell in the second new BRM was not doing justice to it, and while Behra was at the pits investigating his brakes Schell’s engine went woolly and he came in for a change of plugs, dropping down from seventh place to last. On the 31st lap Moss was right behind Hawthorn and on the next lap he went by into the lead, but it was short-lived for he came into the pits on lap 38 with his engine misfiring. After a long search for the cause it was discovered that a valve cap had come out, probably due to a bent valve, and the timing was naturally all upset, so the third Vanwall was retired and Hawthorn was once more in the lead, over half a minute ahead of the next car, which was the Cooper of Trintignant, he having moved quietly up as the leaders dropped by the wayside, and he was still being chased unsuccessfully by the three Ferraris of Musso, Collins and von Trips.

“Nobody was more surprised than Trintignant when he came round in the lead”

On lap 46 nobody was more surprised than Trintignant when he came round in the lead, for the Ferraris had given the appearance of being indestructible, but no Hawthorn appeared for his car had come to rest after the descent from the station. The fuel pump had broken its mounting on the front of the engine and the drive was no longer effective. This was 1955 all over again, with Trintignant driving a model race and profiting from the misfortunes of his faster rivals, but such consistency of temperament deserves success and by half-distance it was pretty clear that neither Musso nor Collins were going to worry the Cooper, while von Trips was now a long way back, having had a refuelling stop, his car having smaller tanks than the other Ferraris.

Brabham leads Trintignant

Motorsport Images

The two Lotuses were not excelling themselves and were behind Bonnier in his old Maserati, while the two works Coopers were making up time after their stops; Schell had restarted but was many laps behind. On lap 56 Salvadori had gearbox trouble and retired, and at the same time Allison came in for water, and now Trintignant was starting up the hill from Ste Devote as Musso cornered by the tobacconist’s shop virtually below him; Collins was leaving the tunnel at this moment and though the two Ferraris were driving hard the Cooper was running comfortably within its limits and maintaining its lead.

Von Trips was now a lap behind in fourth place and then came Bonnier, Hill, Brabham, Schell and Allison, these being all that were left from the imposing starting grid. Lap 60 ticked by and then lap 70, and Trintignant caught up with Brabham and prepared to lap him, but the Australian seemed to think otherwise and kept ahead of the blue Cooper. After a few laps of this Trintignant dropped back and stopped trying to get by; this lured Brabham into relaxing and three laps later Trintignant nipped by when the other driver wasn’t looking. While this was going on Bonnier ran out of road and Hill had a drive-shaft break on his Lotus, and Allison came in for more water.

The Cooper and its two attendant Ferraris were now within sight of the finish of the race and though Moss was urging Collins to catch Musso every time he passed and Bertucchi, of Maserati, was urging Musso to catch Trintignant, the positions did not change, there was still more than half a minute between the first and second and about the same between second and third. As Trintignant went round Ste Devote, Musso came in sight on the pits straight, and as Musso reached Ste. Devote, Collins came onto the pits straight. Poor von Trips coasted in on lap 91 with a seized engine and this let the persevering Brabham into fourth place.

The Cooper never missed a beat, and Trintignant did not put a wheel wrong and once again won the Monaco Grand Prix by consistent and intelligent driving, and not so slow either for his race speed was a new record. To RRC Walker went the honour of winning a World Championship race for the second time in 1958, using a different Cooper and a different driver, but the same team of mechanics. Musso arrived second, a matter of seconds behind the winner, and third was Collins, while Brabham, Schell and Allison were the only others to finish the arduous race. As in the Argentine Grand Prix the order was Cooper, Ferrari, Ferrari, and on both occasions Musso was driving the second car, which puts him in the lead for the World Championship.

Trintignant receives the winner’s trophy from Prince Rainier and Princess Grace

Motorsport Images

MONTE CARLO MUTTERINGS

- Must say the “chummy” atmosphere in the little British teams is refreshing; Allison was seen welding pieces into Hill’s Lotus chassis, and Brabham just will not stop working on all the Coopers.

- Their “science” gives one to think; the bent Lotus was straightened by heating everything with a welding torch and then giving the chassis a big kick, final adjustment being done with a length of string!

- John Cooper was seen using his index finger as a dip-stick on one of the Coopers; at least he’s not likely to mislay it.

- On the other hand, the workmanship on the Vanwalls caused the Osca mechanics to turn green with envy; they would dearly like to have such beautiful pieces of engineering with which to work.

- Of the 16 starters 10 were using disc brakes; could it be that drum brakes are now old-fashioned? Ferrari were the only team not to complain of brake difficulties!

- If the BRM must have trouble it is nice to see it well in the lead when it happens.

NOTES ON THE CARS AT MONTE CARLO

Being the first of World Championship meetings to be held in Europe, the Monaco Grand Prix is always full of mechanical interest, for it is possible to see for the first time any really new cars for the season and all the latest versions of cars that appeared in the Argentine or in smaller races as preliminary sorties.

Mike Hawthorn in the Ferrari Dino 246

Motorsport Images

The Scuderia Ferrari were out in full force with four cars, three of them using the 1957-type space-frame with large-diameter lower frame tubes and cross-members, and of these three only the one Musso drove had the latest forged top wishbones, while they all had the new cast-iron turbo-finned brake drums on the front. These cars had the now standard Dino 246 engine, of 75-deg V6-cylinder layout, with bore and stroke of 85 by 71 mm, giving, 2,417cc, and four overhead camshafts, chain-driven from the crankshaft, with a double-bodied 12-spark magneto driven from the rear of the left-hand inlet camshaft firing the two plugs in each cylinder.

The fourth car has a 1958 chassis on which all the main frame tubes are of the same small diameter tubing, and this also had forged top wishbones. As there was a shortage of Dino 246 engines this car was fitted with a Dino 206, which is of the same design as the Grand Prix engine but of only 2-litres, hence the nomenclature 206, meaning 2.0-litre six-cylinder. The team brought with them a reserve 2½-litre engine for the three principal cars and as none of them blew up in practice it was fitted to the fourth car before the race.

In view of the premium on clear visibility on the hairpins at Monaco and the need for cockpit cooling, all four cars appeared for first practice with cut-down Perspex screens and all except Musso’s car had additional adjustable flat aeroscreens behind the main one, though after first practice Hawthorn removed his curved screen and just had the flat vintage-type aerosereen, The cars all appeared on the first day with the early-type open-top cover round the carburetter intakes, and these were changed to the rear-open bubble-type covers on the second day. In spite of past experience none of the Ferrari cars had any protection to the long nose cowling to obviate damage in the bumping and boring of the opening laps.

Behra enjoys a sea view in his BRM

Motorsport Images

The BRM team arrived with three cars, a 1957 model, the first of the 1958 cars, that Behra drove at Silverstone, and a brand new 1958 car that was completed a few hours before the transporters left for Southern France. In view of the heavy racing programme in the immediate future it was intended that only two of the cars should be raced at Monaco. The three events in which BRM have already appeared this season were essentially in the nature of experiments and consequently the 1958 car is now virtually finalised.

For Goodwood a 1957 chassis was cut in half at the bulkhead and an entirely new frame and front suspension layout was welded on, but this car was written-off in the chicane crash. As an interim experiment it had retained the double-layer stressed-skin cockpit panel, which supplied strength to the centre part of the chassis, but on the new car this idea was dropped; not because it was unsuccessful, far from it, in fact, for it saved Flockhart front serious injury at Rouen last year.

However, it was a costly construction and took a long time to make, so it was decided that while an entirely new chassis frame was being designed it was best to use a normal detachable panel type of bodywork, for it would also facilitate maintenance and accessibility. The new chassis is constructed of small-diameter tubing, all members being in tension or compression, and has a very rigid box-like centre section, with an engine cradle extending forwards, this also carrying the front suspension, and another cradle extending rearwards containing the cockpit, final drive/gearbox unit and rear suspension, all joints on the frame being welded.

Hawthorn chases Brooks down to Tabac

Motorsport Images

Whereas the original BRM space-frame was a thing of horror to students of design, this 1958 frame is a thing of joy of which even Colin Chapman would approve. Hung into this frame are all the components from the 1957 cars, with small modifications here and there, the engine using Weber 58 DCOC carburetters and exhausting through a much tidier and more efficient-looking 1-4 and 2-3 double exhaust system flowing into a long and very large-diameter tailpipe running under the rear axle on the left-hand side. Under the exhaust manifold is mounted the oil tank, suitably screened from the heat, while under-bonnet temperature it kept low by making adequate provision for the exit of under-bonnet air and ensuring that only cold air comes into the engine compartment, all radiator hot air being deflected out sideways.

On each side of the main centre section of the chassis the diagonal frame-tube is detachable and is passed through an aluminium fuel tank, the weight being taken on rubber inserts. The main fuel tank is mounted in the tail and has three similar tubes passing through it, forming a pyramid with its apex at the rear and the triangular base bolted onto the main chassis frame above the differential unit: The four-speed gearbox remains in unit with the final-drive, and behind it, with a single-disc brake on the extreme rear, this disc being cooled by air duets drawing from openings on each side of the scuttle.

Originally a servo for the brakes was driven from the gearbox, supplying a direct multiplication, but this was dropped as any incipient locking of the rear wheels meant that the servo stopped working, which resulted in varying braking power, especially under extreme conditions. The rear suspension layout of de Dion with the cross-tube ahead of the axle-line and located by a Watt-linkage and double radius-rods and suspended on Wag coil-springs remains basically unaltered, while the front suspension is still by double wishbones, coil-springs and anti-roll bar, with ball-joint steering pivots; though the wishbone construction has been re-designed. Mounted on out-riggers from the front of the chassis frame is a small and light radiator, the bottom outlet running straight back through a heat-exchanger coupled to the oil system. Centre-lock Dunlop alloy wheels are retained and Dunlop tyres, while the outward appearance of the 1958 car is similar to the 1957 model, belying the major changes that have been made beneath the surface.

Moss takes time out with his Vanwall team

Motorsport Images

The Vanwall team were making their first 1958 appearance and arrived with four cars, three for the team of drivers and a spare one. It was intended that the spare car should be complete but at the last moment the engine gave trouble while undergoing its test-bed trials and there was no time to rectify it before the vans had to leave so the engine had to be sent on afterwards by air. Unfortunately the aircraft ran into bad weather and crashed, so that the spare Vanwall engine was lost, and the four cars had only three engines between them.

Basically the Vanwall remains unchanged for 1958 and the four cars were all fitted with short nose cowlings and “bumper bars” as used last year and cut-down Perspex screens. Among the changes to the engines, for adaptation to aviation fuel have been altered pistons and compression-ratios, while the exhaust system has undergone complete re-design. Instead of the four pipes joining in a flat convergence sunk into the body, there is now a 1-4 and 2-3 arrangement with the two tail-pipes converging as they leave the engine compartment. The single tail-pipe ends just before the cockpit and feeds into a large-diameter sleeve which runs back to the tail; this sleeve is of larger diameter than the exhaust pipe at the front, forming an annular opening so that the air flow along the body-side enters the sleeve and assists, with the extraction of the gases front the short exhaust pipe.

The chassis, suspension, gearbox and other mechanical components remain unaltered from 1957 but in the search for lower unsprung weight the Vanwall designers worked in conjunction with Lotus design staff and made magnesium-alloy wheels to the same pattern as the ” wobbly-web ” wheels on the Formula II Lotus and Lotus Fifteen. On the front of the Vanwall these wheels contain the wheel races and hub combined, being held in place by a single central stubaxle nut, the brake disc being bolted to the wheel by eight nuts and bolts. This arrangement saves a large amount of weight, not only by reason of the lighter wheel but also it does away with the heavy splined steel hub.

Stirling races past one of the more scenic views on the F1 calendar

Motorsport Images

It is considered by Vanwall that today’s short Grand Prix races eliminate the need for changing front tyres during a race, so there is no need for centre-lock hubs on the front. At the rear it is a different matter, however, and the alloy wheels have been adapted to centre-lock fixing in the interests of wheel changing and tyre wear at the expense of not so much weight reduction as on the front. Additional unsprung weight saving is effected by using the new and light Dunlop R5 tyres in place of Pirelli tyres.

The Cooper works team arrived with three Formula I cars for their two drivers all cars being 1958 models with double-wishbone and coil-spring front suspension and double-wishbone and transverse teal-spring rear suspension. Two cars had new tails, with a slight ” backbone,” and these both had 1,960cc Coventry-Climax engines, while the third car had a brand new 2.2-litre engine front the same manufacturer. This was the first enlarged engine of this capacity, the extra capacity being achieved by increasing the stroke, but this meant extending the cylinder liners so that they protruded above the top of the block, and rather than go to the expense of a new block casting a thick aluminium plate is pressed over the protruding liners, with a gasket between it and the top of the block. The new top surface then forms the face joint with the cylinder head using a second gasket, and the raising of the cylinder head by this extra ¼ in, or so is allowed for in the train of timing gears by an enlarged idler gear. The two works drivers drew lots for this enlarged engine.

Two further Cooper cars were present, these being the RRC Walker cars, one the rebuilt Argentine car, a 1957 mode with transverse, leaf-spring and lower wishbone front suspension and similar rear suspension, the rear hubs steadied under braking by long radius-rods and the gearbox having a bracing clamp over the top drum down to the frame by tension rods, to prevent whipping. The second dark blue car is the 1958 model, with single-wishbone rear-suspension layout, with similar radius-rods, and double wishbone and coil-springs at the front. Both engines had the enlarged liners of 87.3mm, diameter, giving 2,014cc.

Jean Behra leads Tony Brooks as Jack Brabham heads the chasing pack

Motorsport Images

The team Lotus arrived with two 1957 Formula II cars fitted with 1,960cc Coventry-Climax engines, both cars having the new positive-stop gear-change mechanism. They were also fitted with starter motors, current being supplied from an accumulator trolley with a pair of plug-in leads to a socket on the chassis frame. The car driven by Allison had a hydraulically-operated clutch, the pedal arrangement and actuating mechanism being similar to that used on the Lotus Fifteen sports car. Allison’s engine was fitted with Weber carburetters and Hill’s car was on SU carburetters. This team, like Cooper’s, also had their first 2.2-litre engine but it was left sitting in its box as a reserve.

In addition to all these cars were various ” independents ” with Maseratis, Godia and Scarlatti with last year’s works cars, Bonnier, Miss de Filippis and Testut with their earlier cars, and the Scuderia Centro-Sud with their two cars supplemented by Gerini with his ex-Piotti car. To complete the field were two 1,500cc sports Oscas of the latest type, devoid of all normal sports equipment, and a lone Connaught front the Ecclestone stable, this being the blunt-nosed B7 car.