Brooklands: birthplace of British motor sport

For Motor Sport and British motor racing, this is where it all started. Gordon Cruickshank visits Brooklands to compare what we said then with the actual cars today

JONATHAN BUSHELL

Brooklands: birthplace of motor sport – and of Motor Sport. For years the Surrey autodrome, first race circuit in the world, was the centre of motor racing in Britain, and in 1924 it duly triggered the launch of this magazine as The Brooklands Gazette.

Though we widened our horizons from 1925, every issue until the circuit closed in 1939 contained some news from the Track, on cars, people or races. There was always something going on and usually someone from MS was there to see it – frequently Bill Boddy, Brooklands’ arch proselytiser.

Having devoured the first editions of The Brooklands Gazette and visited the track in 1926, WB’s first published article was in MS in 1930 – on the history of Brooklands. Already he was looking to the past.

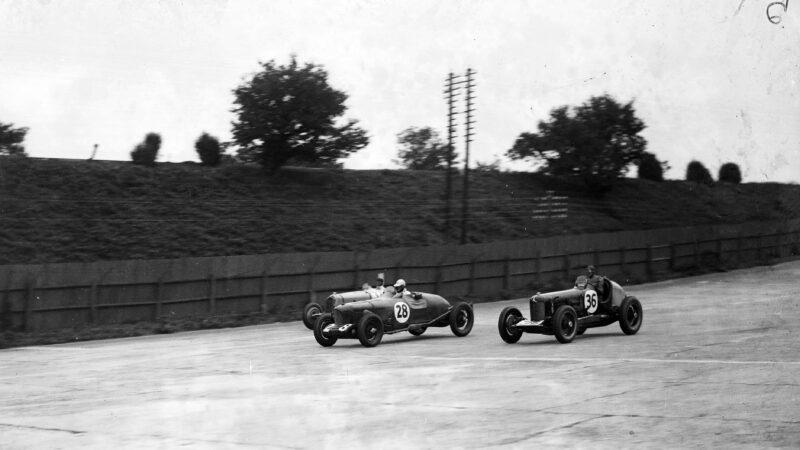

Brooklands, British Grand Prix, 1927 – although Motor Sport was far from amused with the Delage 1-2-3

Getty Images

Even before he became our editor in 1936 WB had worked at the Track on a rival Brooklands magazine, in thrall to the drama of the vast speed bowl. Here he absorbed every detail from valve gear to lap times, recording them in neat notebooks which would be vital to compiling his definitive History of Brooklands Motor Course.

After WWII Boddy tried to gain support for reopening the track, punctured to give take-off clearance for the Wellington bombers built there, but it was a forlorn hope. The racing world had moved beyond artificial speed bowls into road racing, and the Track lay weed-grown and ignored. Boddy, though, continued his Brooklands fascination in our pages right up to his death in 2011, recalling the events, characters and machines from 350cc Jappic to fiery aero-engined monsters built to pound round its concrete heights, like the Fiat Mephistopheles and Napier-Railton.

WB was central to preserving the circuit, and it’s to his credit that the museum exists today. To recall this link, we extracted from the collection some of the cars we wrote about then, together with our period comments.

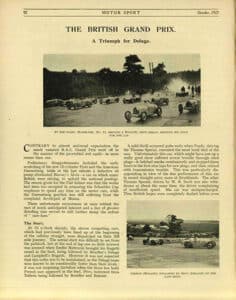

Delage 15-S-8

A unique survivor of the two grands prix held at Brooklands, the sophisticated Delage dominated the 1927 European season, including a 1-2-3 victory at the Track. Albert Lory’s supercharged eight-cylinder motor boasted 170bhp from its 1.5 litres, revving to 7500rpm, and its four 1927 victories made Robert Benoist a champion. The car in the Brooklands collection was the team spare in the 1926 GP here – technically the RAC Grand Prix, not British – and although the identities became muddled it was certainly one of the three leaders in 1927. But this utter defeat for Britain prompted editorial outrage in MS.

What we said: October 1927 Wake Up England!

ANOTHER racing season is drawing to its doleful close. In the last International Race, England has made one of her most feeble exhibitions. Here in our own country not only do we fail to secure a place, but fail to finish at all. Far be it from us to depreciate Delage in their victory, but we feel that England should at least be capable of a team finish.

To say that the result of the Grand Prix has disgusted English sportsmen is to put it mildly, Something must be done for the honour of England. For months past we have pointed out the steady decline in our racing activities, and the way we are drifting. The time has come for a definite attempt to stop the rot, and to place the industry back on the pedestal from which it is slipping fast.

What we said: October 1927 The British Grand Prix: a triumph for Delage

Contrary to expectation the much-vaunted RAC Grand Prix went off in the manner of the proverbial wet squib – in more senses than one. Rain served to still further damp the ardour of ‘race fans’.

As the Delage team were known to be faster than their rivals it was not surprising when the three French cars appeared in the lead, Divo followed by Bourlier and Benoist.

One Thomas Special retired with transmission trouble and the other was also withdrawn. Thus British hopes were dashed before even the leaders had been announced for the first 10 laps. It was remarkable to notice that for lap after lap the three Delages came round in a group, while separated from them by about half a lap a covey of five Bugattis were lapping in close formation.

The race continued monotonously, without any thrills. Just after half distance most drivers stopped for replenishments, Bourlier shed his mackintosh at 69 laps, thus giving the lead to the Delage ‘ace’ Benoist, but still keeping ahead of Divo.

Benoist soon finished first at an average speed of 85.59mph for 325 miles in rain, the other two Delages just behind. Benoist thus won his fourth big race this season, a remarkable tribute to his skill and to the technical ability of the Delage racing staff.

What we said: March 1943 Racing car evolution part III, 1926-1927

The Delage proved quite invincible, and for a decade no one was able to produce a more powerful engine of its size, and it stands to this day as a high-water mark of efficiency. When one reckons that the engine incorporated 21 gears, 48 valve springs and 32 piston rings, it becomes clear that Delage were in no mood to let complications and expense in design stand in the way of the best possible results.

For five years grand prix races had had the support of many leading manufacturers, who had been willing to spend £50-100,000 per annum in the construction and operation of special racing cars. Everyone seemed to decide at once that this was excessive.

Robert Benoist, sixth from left, with a Delage in 1927 – the year he won four GPs

Alamy

|

Manufacturer: |

Delage |

| Year: | 1926 |

| Engine: | 11⁄2 litres, eight cylinders |

| Max speed: | 130mph |

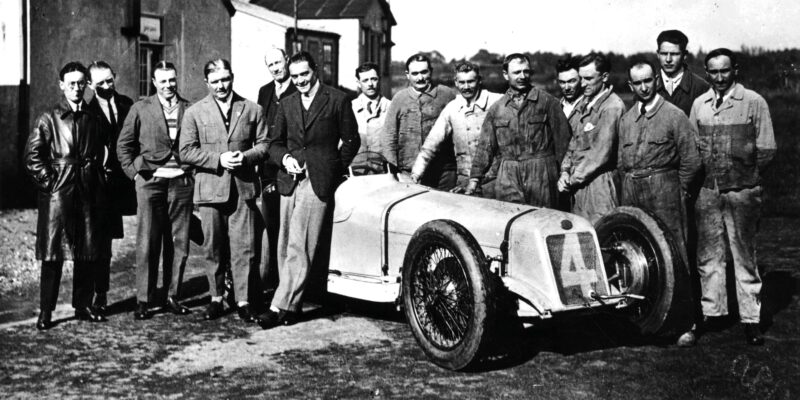

Napier-Railton

Designed by engineer Reid Railton, this fearsome machine was built for John Cobb to break speed and endurance records – and to race at the Track, where it scored many victories. Cobb also set the ultimate Brooklands lap record in it, a never-to-be-beaten 143.44mph. Postwar, it featured in a romantic film, Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, and served for testing aircraft braking parachutes. With its 24-litre W12 aero engine it was the apotheosis of the Brooklands Special – at the same time magnificent and redundant, a symbol of how UK racing tech stalled compared to continental racing-car development.

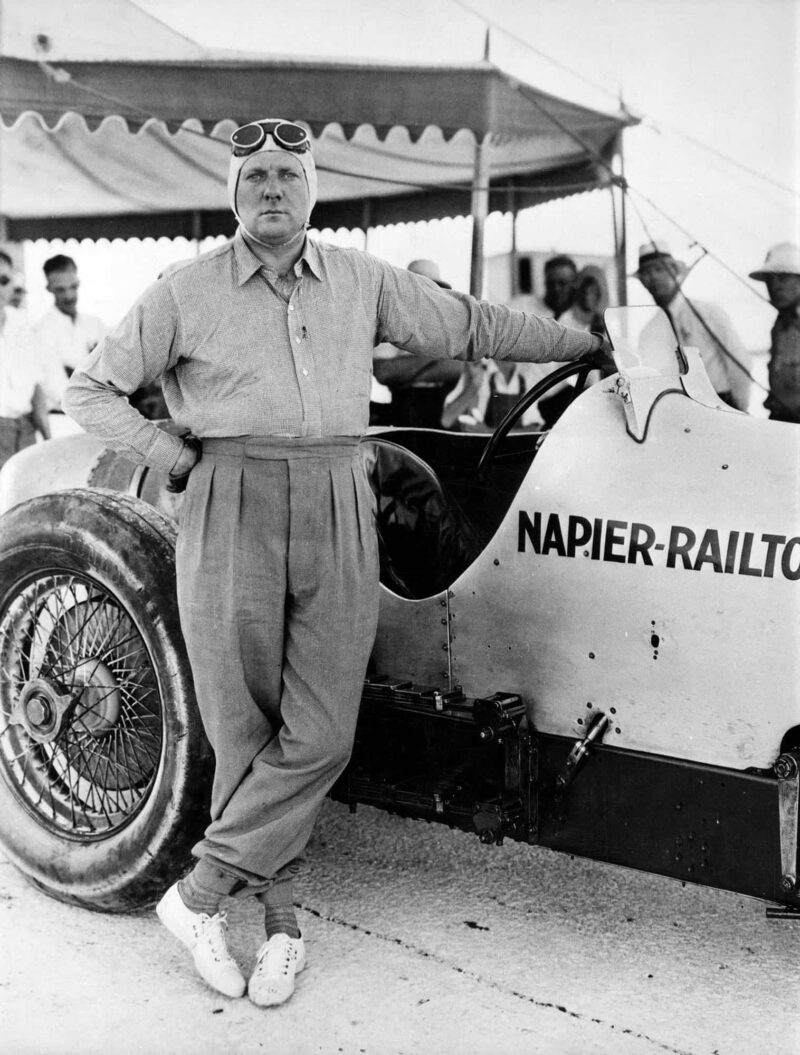

John Cobb and the Napier-Railton, Bonneville Salt Flats, 1935.

Victory at the 1937 Brooklands 500Kms

Getty Images

What we said: August 1933 Built for Brooklands and Montlhéry: the Napier-Railton passes its first tests in the hands of John Cobb

After many months of hard work by all those concerned with the project, the new 12-cylinder Napier-Railton car has at last reached the stage of completion, and was formally ‘launched’ on the Tuesday following Whit-Monday at the Brooklands premises of its constructors, Messrs Thomson & Taylor, Ltd.

The engine is a 500hp Napier Lion aero unit, modified for ground work, and the power reserve is indicated by the fact that 120mph only requires 250hp from the engine. The oil and fuel tanks only contain supplies for 2½ hours running – the limit of the car’s tyre-wearing capacity.

The car was demonstrated to a gathering of friends last month, and John Cobb announced that it handled perfectly and was all ready for its first public appearance at Brooklands on August Bank Holiday.

In appearance the body is not unlike that of the old Delage, with a fairly short tapered tail and a striking frontal aspect given by the curved strengthening rib in front of the radiator. The seat cushion and squab are each about 12 inches deep, and with the controls all within reach the driver should have a comfortable ride.

What we said: September 1933 August Bank Holiday at Brooklands: magnificent debut of the Napier-Railton

Don made a slightly better get-away than Bertram, and then three seconds later Cobb let in the clutch. Never have we seen such colossal acceleration. The aluminium car simply leapt forward in a steady surge of joyous power, and caught the Delage going onto the Railway Straight. Don was the next victim, and in one lap the 26 seconds start of Bouts’ Leyland Thomas had been wiped out. Now came the danger point. Cobb was right behind the Leyland all round the Members Banking, trying to pass right at the top of the track. The Leyland was too high, and suddenly Cobb saw the gap narrow in front of him. Somehow he managed to draw back, a great cloud of dust testifying to the danger of the incident, and passed Bouts later on the Railway Straight.

Don seized the opportunity to drop down and pass both cars below, but Cobb soon got clear, and at once took the lead to win by 200 yards, after a most thrilling race. The performance of the car was not merely impressive – it was astounding.

Jonathan Bushell

Jonathan Bushell

Jonathan Bushell

Duesenberg single-seater

A one-off machine with a very close connection to Motor Sport – after its racing life it became for many years the property of Denis Jenkinson, who eventually bequeathed it to the Brooklands Museum where it now rests. In its short career it raced under the Prancing Horse banner of Scuderia Ferrari, though its origins were less exalted.

Scuderia president Count Trossi commissioned it from Augie Duesenberg, who cannily fitted an eight-cylinder Clemons engine into a 1927 single-seater Duesenberg chassis for him. Trossi drove the gawky machine in the 1933 Monza GP but it was then set aside, before Whitney Straight jumped in it for an attempt on the Brooklands lap record, reaching 138.15mph. Subsequently modified by Jack Duller for the Outer Circuit, it had many drivers including Dick Seaman and Gwenda Stewart and raced on until the very last event on the Track in 1939. Despite its mixed pedigree it remains the fifth-fastest car ever to lap the track.

Although Brooklands devotee Bill Boddy tried in 1950 to buy it, Jenks beat him to it, causing mild but lasting friction between them. It had lost its Clemons engine but DSJ managed to obtain that, intending a full restoration which never happened. The museum is now working on it.

What we said: July 1968 A question of identity

Hidden away in Wales I have a single-seater Duesenberg racing car that was brought from America by the Scuderia Ferrari in 1933 and driven briefly by Count Trossi at Monza. Then Whitney Straight borrowed it and later it was bought by Jack Duller, and it spent the rest of its life at Brooklands Track. I get immense pleasure from looking at it and sitting in it and thinking of all the famous people that sat in that same cockpit. How do I know it is that self-same car? Mainly because it was the only one to come to Europe and its history can be traced through the bound volumes of Motor Sport. The only disturbing thing in this story is that it is no longer the same as when Count Trossi and Straight drove it, for when Duller bought the car his tuning establishment made it more suitable for Brooklands by altering the driving position, having a new tail-cum-fuel tank made of larger proportions, widening the rear spring base, fitting different shock-absorbers and re-upholstering the cockpit. I cannot say I have the original Duesenberg, merely the 1936/39 modified Duesenberg, everything about the car being as it was in 1939 when racing at Brooklands ended. DSJ

The Duesenberg, right, in the Brooklands 500 Miles, 1935. It was later owned by Jenks

LAT

|

Manufacturer: |

Duesenberg |

| Year: | 1927 |

| Engine: | Clemons 41⁄4 litres, eight cylinders |

| Max speed: | 150mph |

Barnato-Hassan Bentley

Having relinquished chairmanship of Bentley Motors and with a distinguished track career behind him, including three Le Mans victories, Woolf Barnato retired from racing after 1930. But keen not to drop out of this world he commissioned famed engineer Wally Hassan to build a new Brooklands Outer Circuit special to challenge the record. Trained at Bentley, Hassan had become Barnato’s personal mechanic and would later join Jaguar, shaping the XK and V12 units, and he was also central to the racing success of Coventry Climax engines.

What we said: November 1973 Hassan Specials

The car was built in Barnato’s garage in Belgrave Mews, W1, during the winter of 1933 and spring of ’34. [Hassan designed] a frame, narrow and underslung beneath the back axle, with deep side-members. Although this was a single-seater the steering was not centralised, so the driver sat on the offside of the slim body. This had an oval cowl enclosing radiator and dumb-irons and the tail fell away, The exhaust pipe and Brooklands silencer were faired into the nearside of the body, which had been made by a small firm in Camden.

After mudguards made from strips of timber were fitted the Barnato-Hassan was driven to Brooklands, doubtless to the relief of Barnato’s London chauffeurs, who had never been happy with a racing car in their midst and the possibility of scratches being inflicted on the road-going cars in the garage.

Hassan worked during the winter at Thomson & Taylor’s, the car ever after living at the Track, installing an 8-litre Bentley engine with triple SU carburettors supplied with air through a long ram-pipe alongside the bonnet on the left side. The improved car was entered as the Barnato-Hassan Special by Captain Woolf Barnato for the Easter races. The driver was the young barrister Oliver Bertram, a very good driver who had been racing the ex-Cobb 10½-litre V12 Delage. How he became associated with Barnato is obscure but it seems likely that he gave his services as the new car’s driver out of enthusiasm, with no thought of financial gain.

Thus the appearance of this car, accompanied by multi-millionaire Barnato and the blond young Bertram with his fashionably dressed lady friends, Hassan in work-soiled overalls in close attendance, was one of the outstanding features of the Brooklands Paddock at this time.

[At the1935 Whitsun Meeting] Bertram later came out for a solo attempt on the lap-record. In this he was successful, the new record being at 142.60mph. It was a magnificent achievement to have bettered Cobb’s record by 0.83sec with a car of one-third the engine size, apart from which the Barnato-Hassan Special was a decidedly difficult proposition to control,

Oliver Bertram with some welcome assistance in the Barnato-Hassan

In September Cobb regained the record, with a time 0.41sec quicker than Bertram’s, this being the 143.44mph record.

During the winter Hassan evolved a slimmer body for the car, the driver now sitting centrally, the steering was raked, and a streamlined tail with headrest and fairings were used over the frame and springs. The funnel air-intake was elaborated. The car looked impressive and exciting but in retrospect Hassan wonders whether there was really much improvement in streamlining.

[In 1938] now running a mix of petrol, benzole and alcohol, at the Dunlop Jubilee Meeting Bertram achieved a lap at 143.11mph, only 0.33mph below the absolute. As this was accomplished in a race it was not recognised as a new Class-B figure but the car’s former 142.60mph speed stands as this.

|

Manufacturer: |

Woolf Barnato & Wally Hassan |

| Year: | 1934 |

| Engine: | Bentley 8 litres, six cylinders |

| Max speed: | 140mph-plus |

Aston Martin Halford Special

In the 1920s, in between designing aero engines in World War I and becoming de Havilland’s chief engine designer, Major Frank Halford devised his own racing car engine, fitted it in an Aston Martin chassis and raced it at Brooklands. Motor Sport’s long-time editor Bill Boddy was fascinated by specials, particularly the vast aero-engined leviathans such as the various Chitty-Bang-Bangs that pounded round the vertiginous rim of Brooklands track. But small engines appealed too, and as WB found out the unique Halford was a power-boosting pioneer.

What we said: April 2008 How Halford broke the mould with DIY special

Many special racing cars were built for competition at Brooklands. One outstanding example of these was the Halford Special, which made its debut in 1926 and won on its first appearance. Frank Halford began racing at Brooklands with a Bamford & Martin Aston Martin [but wanting] to have a car suitable for long-distance races he designed and built the Halford Special. It had a twin-overhead-camshaft six-cylinder engine with a short stroke to keep the capacity within the 1½-litre limit. The seven-bearing crankshaft ran on plain bearings. The camshafts were driven by a train of spur gears at the rear and ignition was by two magnetos driven from the camshaft gears and protruding through the bulkhead. They fired special KLG sparking-plugs, two plugs per cylinder.

A significant link with aero-engine practice was a turbo supercharger, exhaust driven, sucking from the carburettor. This centrifugal blower was set below the sump, feeding to the crankcase though a connecting passage. This was revolutionary for a British racing car at the time. However [due to disappointing results] it was replaced by a normal Roots-type supercharger situated ahead of the car’s radiator and driven by a universally jointed shaft from the crankshaft, the starting handle operating through it. Two such engines were built, the output of the first one quoted at 96bhp at 5300rpm and the second 120bhp at 5500rpm with 11lb boost from a supercharger. They were built for Major Halford by The Weyburn Engineering Co of Elstead, Surrey.

They were installed in a side-valve Aston Martin chassis, thought to be the one previously raced by George Eyston and Barlow and now entered as the AM-Halford.

In the 1925 JCC 200-Mile race, Halford managed fourth place in the kind of contest for which he had intended his car should be used. But it was in the 1926 RAC British GP at Brooklands that the Halford Special, painted green, was mixing it with the Delage and Talbot teams, when a universal joint of the aged Aston Martin failed.

Frank Halford with admiring Brooklands crowd, BARC Whitsun Meeting, 1926

During 1927 Halford was not available, so Eyston, who was also driving a B&M Grand Prix Aston Martin, deputised for him, to no avail. But the Major must have been very happy with the performances of his own car and there was an additional accolade. The BARC had decided to stage a beauty contest among the cars before racing commenced, and the Halford Special with its white body, aquamarine chassis and black wheels, with a tiny plaque at the top of its radiator inscribed ‘Halford’, was the first winner.

|

Manufacturer: |

Frank Halford |

| Year: | 1925 |

| Engine: | 1.5 litres, six cylinders, supercharged |

| Max speed: | 120mph |

And don’t forget…

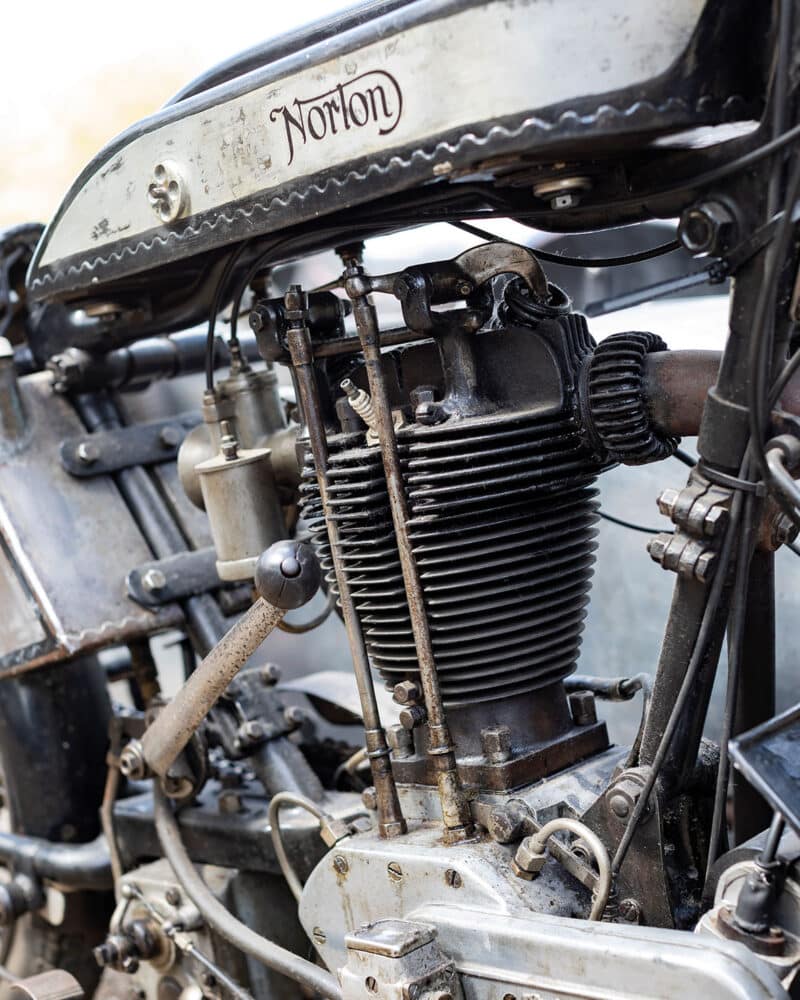

Brooklands is also home to significant racing motorcycles

Don’t imagine that Brooklands was only about cars. With a landing strip down the centre, aircraft assembly and maintenance and a busy flying school were part of the daily mixture. Remember the moment in the 1965 film Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines when an aircraft crashes in a sewage farm? That sewage plant existed here and yes, aircraft did sometimes crash in it. The flying club house still exists outside the grounds of the Brooklands Museum.

Then there were the motorbikes. Those vast concrete expanses and high bankings allowed for plenty of racing and record-breaking, and the museum has a large selection of two-wheeled power on display – some rolled out for our shoot.

An entrant in the 1927 and ’28 motorcycle grands prix here, the Museum’s Norton TT Model 18 was prepared by the works racing department to contest the new and windier mountain circuit at Brooklands. Later it took the 24-hour record at Montlhéry, the banked autodrome near Paris.

Norton soon became a byword for racing success, especially with its postwar Manx model, and much early development took place here. Known as ‘LPD1’, this machine with its ‘streamlined’ sidecar broke 14 distance records on the banking in 1927 before Bert Denly took it to Montlhéry to become the first man to achieve 100 miles in the hour on a 500.

Brave Brooklands racers who lapped the track at over 100mph received the BRDC’s coveted Gold Star, something Wal Handley achieved in 1937 on a 500cc BSA single. The firm adopted the label for its sports bikes, among the fastest of the 1950s and hugely successful in road races, trials and scrambles – and that famous Gold Star name stems from what went on here in the glory years of Brooklands.

Jonathan Bushell

Jonathan Bushell

Jonathan Bushell