Blown and exhausted: why detail matters

Adrian Newey on squish loss, the Coandă effect and fumes fixes

Step aside Fiona Bruce –Rear of the Year 2010 was the RB6 with its exhaust tailpipes at floor level

Grand Prix Photos

One thing that was particularly interesting during my time was improving performance through the blown exhaust. We’ve played with exhaust positions at various times over the years. The regulation change that came in 1995 was that you weren’t allowed to see the exhaust exiting from underneath the car, so most people responded by either putting the exhaust out the back, which is what we did at McLaren in 1998 and ’99, or through the top bodywork, which is what Ferrari started doing in ’98.

Around that time I realised you could position the exhaust exit underneath to blow the diffuser, within the so-called boat-tail so it couldn’t be seen, because it was shadowed by the plank when viewed underneath. So that’s what we did for the 2000 car and it worked really well. That, of course, then got banned and lasted only one year.

But when it came to 2010 and the double diffuser cars, we realised that with a vertical slot in the diffuser around the rear axle you could put the exhaust out the side for it to blow through the slot – and it was totally legal. That became very powerful again.

The thing you usually struggle with when it comes to blown exhausts, which happened when Lotus first did it in the mid-1980s, is that in off-throttle phase of braking and entry to corners you lose a chunk of downforce at the rear and the car becomes very unstable. Ayrton Senna was famous back then for pressing both the brake and throttle at the same time to keep the flow and stabilise the car on entry – probably the only person who was able to do it.

Because of that factor, when I was at Williams when we still had the exhaust blowing through the diffuser in the early 1990s, we started working with Renault to try to keep the exhaust blowing at all times. The idea was you’d keep the throttle butterflies open even on overrun and then control power on spark cut and ignition timing to keep the engine’s mass flow going. That work came to a stop just as we were about to start racing with technology because of the 1995 regulation change.

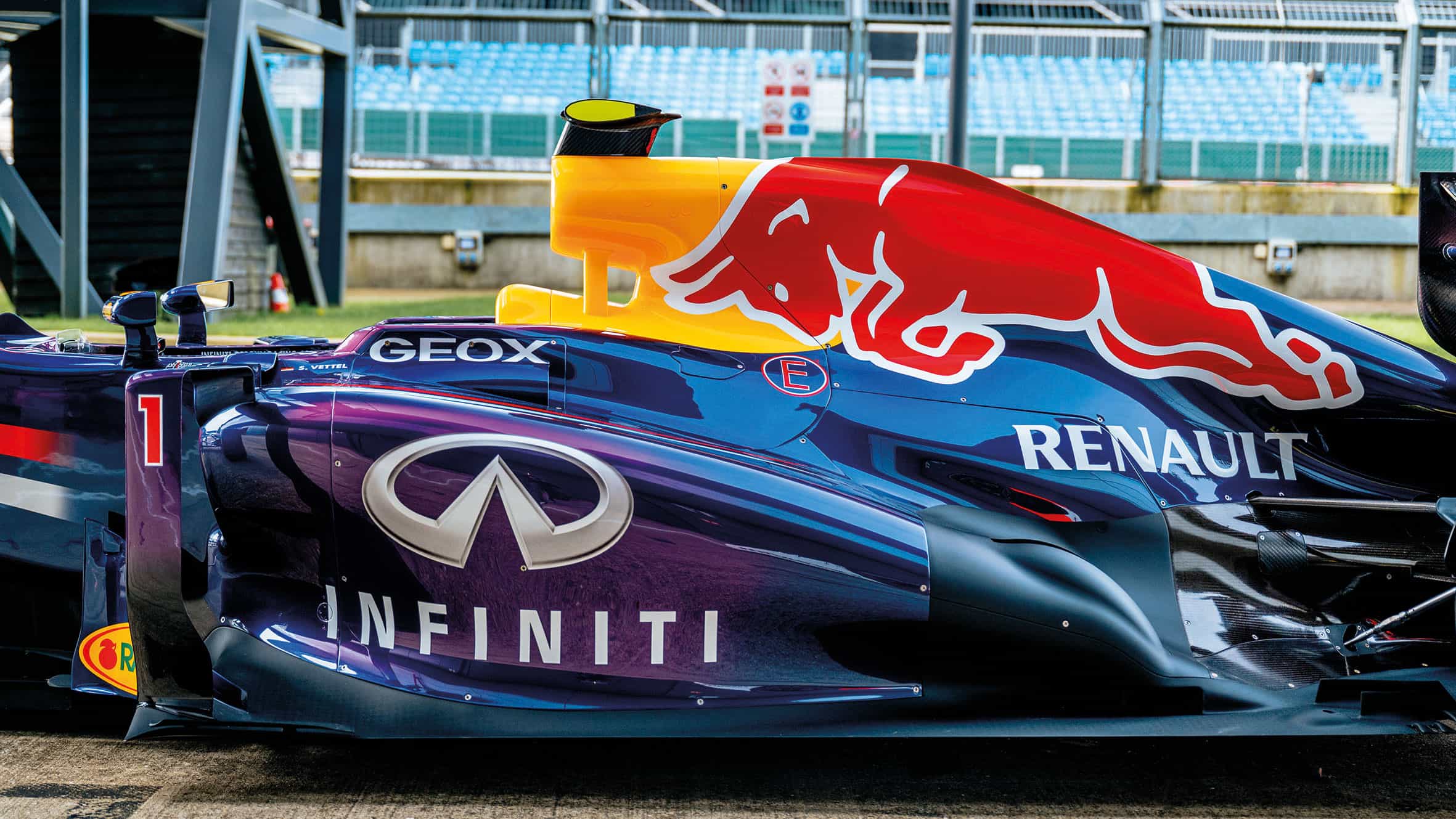

Red Bull’s 2013 RB9 made it into Motor Sport’s Race Car of the Century shortlist – which we photographed at Silverstone in April

Fast-forward to 2010 and into 2011 with Red Bull, working again of course with Renault, we asked to revisit that idea we’d pursued with Bernard Dudot back in the 1990s. Renault did a great job of picking that work back up again, and at the same time in 2011 when the double diffuser was banned we asked how we can still use the exhaust. The answer was to put it out on the top surface of the floor, just by the rear wheels to help suppress what we call the ‘squish loss’ – which is the squirt of dirty air that comes out when the wheel contact patch meets the ground and you get this jet of air coming out sideways which affects the diffuser. So we started working on that and it was incredibly powerful, actually more powerful on track than we expected from what we’d seen in the wind tunnel and on CFD.

Then of course came the question of why was it more powerful? We started running what is called transient CFD, which is time dependent and meant we modelled the pulsing of the engine and looked through various commercial papers to look at how pulsing effects entrainment. Through that we realised that actually the pulsing was a positive and powerful effect. It was one of those very rare things where the on-track performance exceeds what the tools are telling you.

Red Bull success in the early 2010s came with Renault power

Red Bull

So that worked very well, particularly combined with Renault’s strategy – we had all that downforce available on corner entry. And that really suited Sebastian’s style, probably more than Mark’s. There was this myth that Sebastian could cope with an unstable car on entry and just deal with it. What he actually wanted was a really stable rear on entry. He would use that to rotate the car very hard. He’d got it turned more by the time he got to the apex.

Going into 2012 that exhaust position was banned, and there was a new, very restrictive set of exhaust positions, one of the things being that it had to point upwards at 30 degrees in side view. So how on earth do you get that to do anything useful? I had to admit we missed it to start with, but McLaren spotted you could use the well-known Coandă effect where air will attempt to stick to a surface and follow the curvature of that surface. They got that working so we knew we had to look at it. But I didn’t like the way McLaren had done it.

“In the wind tunnel it looked really good. On track it wasn’t working”

Instead, we exploited a loophole in the regulations that said anything below 100mm above the bottom of the car – so above the top surface of the floor you could have a letterbox opening. That allowed us to maintain a Coke-bottle sidepod shaped underneath, but have a complete conduit of the exhaust down to the area ahead of the rear wheels. That in the wind tunnel looked really good. On track it wasn’t really working. And the answer again was this transient thing, where the engine pulsing was now the exact opposite to what we wanted. The pulsing was creating an anti-Coandă effect where it was stopping the flow sticking to the surface. We talked to Renault and simultaneously Ferrari came up with a similar thing, which was a resonator in the exhaust system tailpipe which absorbed all the pulsing to allow it to act in a steady state. Suddenly the performance started to pick up.

So now we asked how do we increase the gas velocity? We worked with Renault further to reduce the tailpipe exit diameter so it almost looked like a two-stroke exhaust, and that was even more powerful. Through 2012 and 2013 we developed that exhaust effect and it became incredibly powerful.

Vettel on the up – as was the direction of his exhaust.