Adrian Newey — The rise of the machines in 2010s racing

With Adrian Newey in charge of Red Bull design throughout the 2010s, world championships arrived. The grand draughtsman reveals the tricks of his trade – and gives some pointers to improving the sport

You’re born when you’re born, and I’m happy with my time. But looking back, the 1970s must have been a fascinating era to work in Formula 1, which went from the cigar-shaped tubes of the mid- to late-1960s to a huge explosion of shapes. Motor sport then was a product of very few lines in the rulebook so you had a huge amount of freedom, but very limited research capabilities.

My influences included, first and foremost, Colin Chapman, obviously because he was a significant designer, but also because Dad had three Lotus Elans, including a Plus 2, two of them built from kits. Then as I got a bit older I became fascinated by the Chaparrals and Jim Hall. It’s interesting how often things now commonplace in F1 were first popularised in sports car racing: monocoques and disc brakes for the Jaguar D-type; wings with the Chaparrals, plus the fan car concept; fuel injection too. Even today racing teams are not big enough to be research institutes, so we plagiarise and use whatever we see available. That’s something that hasn’t changed.

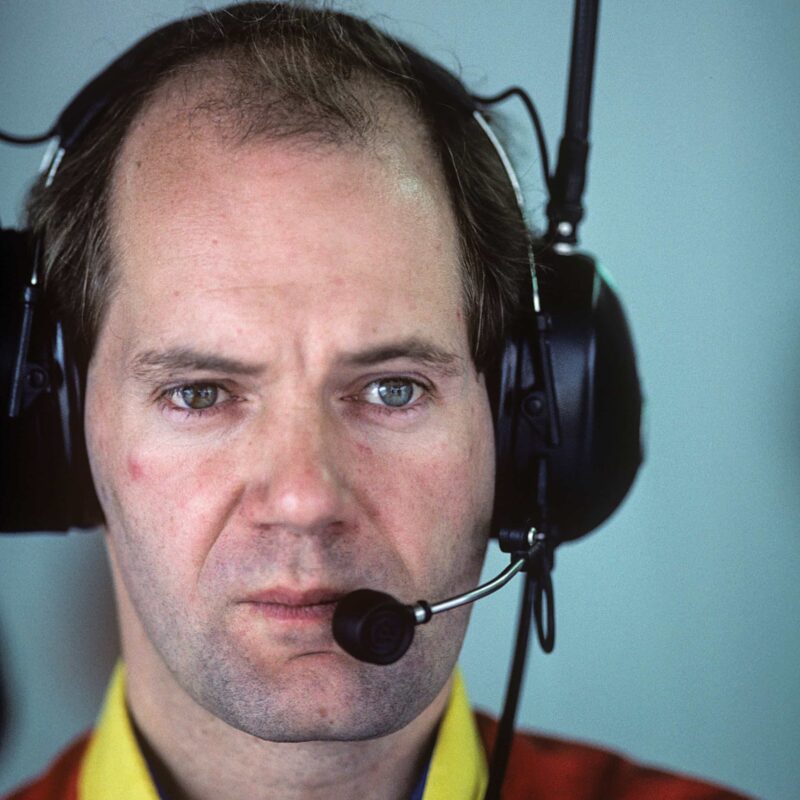

Adrian Newey, Leyton House technical director, 1990

Two years later Newey’s Williams FW14 helped Nigel Mansell take the F1 world title

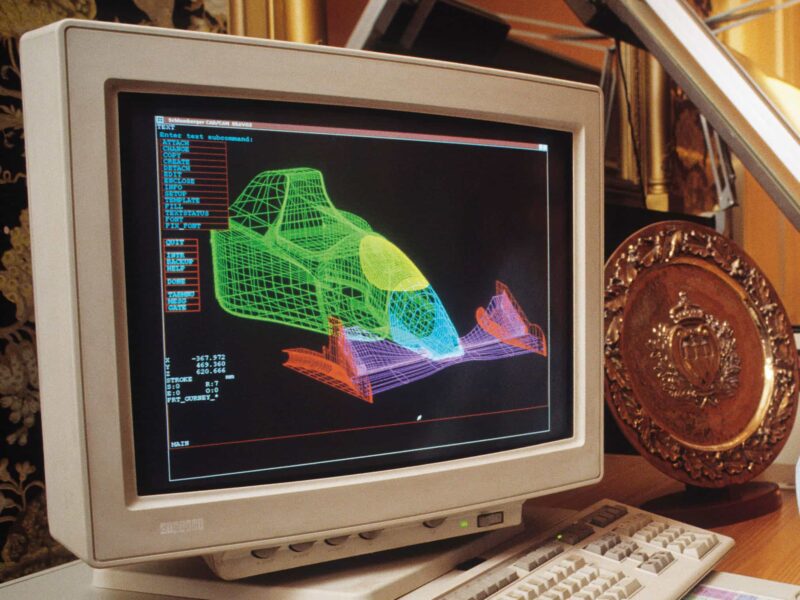

In my time, computing power is the biggest development in racing car design. When I started, wind tunnels were in use but teams didn’t have the budget to properly make the most of them or indeed employ aerodynamicists. When I joined Fittipaldi in 1980 straight out of university my position was junior aerodynamicist – which turned out to be also senior aerodynamicist as well! It’s quite remarkable when we look at where we are today. The surge in greater computing power started to show signs in the very late 1980s, but in reality it was into the mid- to late-1990s that it really kicked in. That also reflects to an extent in the headcount of the teams. Team size was also finance limited, but at Leyton House in the late 1980s we were about 50 people, and the big teams like McLaren, Ferrari and Williams were probably in the low 100s to 150 tops. That wasn’t so much budget limited, it was more that without the simulation tools you wouldn’t have known what to do with more people – they wouldn’t have really helped. Once you had that computing power kicking in, coinciding with bigger budgets, the sky was the limit. You could go into so much more detail in every area and be reasonably confident that work would pay dividends.

“In my time, computing power is the biggest development in car design”

It’s well known I still use my drawing board, but it’s just a tool, it’s what I’m familiar with. But whether you use a drawing board or CAD it doesn’t matter – it’s just a way of getting thoughts in your head down in a medium from which you can then develop them. Through experience and perhaps from a natural gift from a young age, I seem to be quite good at visualising things in 3D, then develop them in 2D on a drawing board.

Sebastian Vettel, in Newey’s RB6, takes his first F1 win of 2010 in Kuala Lumpur.

Getty Images

Partisan fans at the 2014 Spanish Grand Prix

Grand Prix Photo

I’m often asked whether flair and innovation are constricted in the modern age. My answer is it’s different today. The big visual changes – chassis and bodywork shape, engine configuration and the number of cylinders – yes, it’s true: the cars nowadays look relatively similar to each other and that’s a product of regulation and convergence. But there is still a lot of concept work that goes into these cars, it’s just in a more confined area. As the rules become more restrictive you get hemmed into smaller areas, but equally the tools keep developing to allow you to explore those areas in more detail. So I don’t think that makes it less interesting, just different. It’s a bit like comparing a Spitfire to a modern fighter jet.

Having said that, I would love the rules to be more open. There are two arguments given for having restrictive rules. One is to try to control costs, and the other which has never really been advertised but is definitely a factor, is the fear that one team would read a more open rulebook better than others and disappear into the distance. With the cost cap now in place taking care of the first part, there’s a good argument to open the rules up and get some more visual differentiation. That, of course, leaves the fear that one team will disappear. But even with the very restrictive regulations, that can still happen! Also bear in mind that since the cost cap has been introduced the competitive order hasn’t really changed so in that sense you question how much it has really brought.

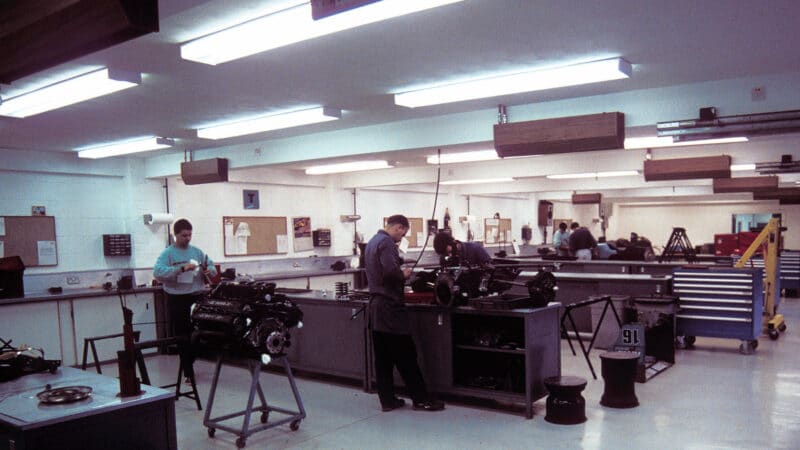

The March premises at Bicester, where Newey designed his first F1 car, the March 881

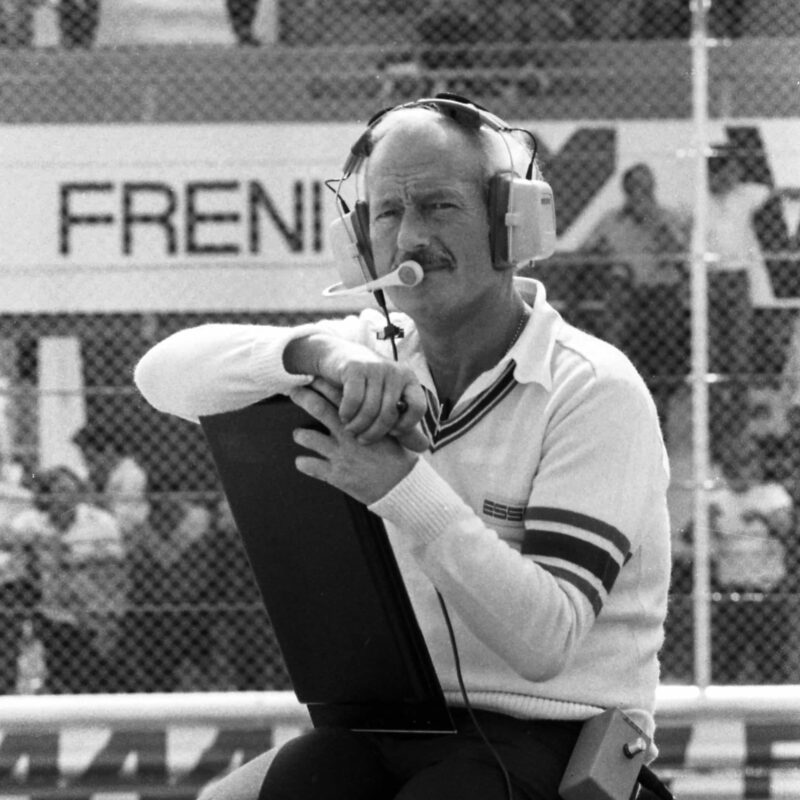

Lotus’s Colin Chapman – an inspiration

Getty Images

I do think trying to contain an arms race is a good thing to do. But I’m not convinced the way it’s done is right. The cost cap has a lot of shortfalls, some of them not immediately obvious when it was introduced. For instance, because it is a cost cap and not a people cap we as an industry can’t keep up with inflation. So F1 has gone from being the best-paid engineering industry in the world to most definitely not any more. A lot of start-up electric car companies, tech companies and other racing series are now actually better paid as an industry than F1. At Red Bull we aren’t alone in losing people – not to other teams, but other industries. The same is true when it comes to hiring undergraduates. We are no longer offering the highest salaries.

“Some say F1 is a championship for engineers, not drivers. It’s meant to be!”

Some say F1 is a championship for engineers rather than drivers. But it’s meant to be, isn’t it?!?! Of course, it should be a combination, that’s what makes motor racing in general and F1 in particular unique in the world. Outside of motor sport, there’s America’s Cup yachting, but little else that combines man and machine in sport to such a high degree. Within that you have three facets: the driver, the chassis and the power unit. Fundamentally that has never changed. I seem to remember everyone was moaning when Fangio and Moss were disappearing off in the Mercedes in 1955, or Lotus with Andretti and Peterson in 1978. It’s always been the same.

I joined Red Bull in 2006 from McLaren with a blank canvas to work from. In that sense it was exactly like Leyton House in the early days, but with much better funding. And in my case considerably more experience. That ability to mould the team and create the right environment to stimulate and encourage creativity I hope made it attractive for good engineers to join here. We won our first race in 2009 and became world champions with Sebastian Vettel in 2010 – a relatively short time. But it felt like forever in the first two years! When I first arrived I probably made the mistake of trying to get the team to run before it could walk. Certainly the 2007 car, the RB3, was probably a bit too ambitious for the experience we had in the team and that was a lesson to me. I actually needed to spend more time developing the infrastructure and less time concentrating on the design of the car. That’s very much what we did through 2008, knowing that we had an opportunity with a big regulation change in 2009.

An inspection of the RB6 front wing before a Red Bull 1-2 in the 2010 Japanese GP

Computers have meant less risk-taking for designers

DPPI

In terms of our run of four successive titles between 2010 and 2013, first of all I’m proud that we got the concept right for the 2009 car. If you can manage to achieve that it’s so key with a new set of regulations because if the first car you produce is architecturally sound you can evolve from that. If you have taken the wrong path and after a year or two have to completely change, you are always on the backfoot. The good thing about RB5 was that the architecture was good. Yes, we didn’t have a double diffuser, but once we had bodged that on to the car and did a proper job for 2010 we had a decent product.

We had a good double act with Sebastian and Mark Webber. Like all top drivers, it’s primarily about feedback, in as much as Sebastian had a good feel for the tyres, and when the Pirellis came in that stood him in good stead, and Mark was sensitive to the aerodynamics, so we had good feedback on the two key areas.

The RB6 of 2010 gave Red Bull’s Vettel the first of four consecutive Formula 1 world titles

When the hybrid era began in 2014 we found ourselves on the backfoot. To win championships rather than snatch the odd win, you need a good driver, chassis and engine – those important precepts. You can still win championships without the best one of those parts but if one of those is actually weak you just can’t do it. The reality is the Renault hybrid was so far down we had no chance. It was a depressing era. By the middle of 2014 it was apparent we were well down, but it was also apparent that Renault from the top level had no determination to try and fix it. There were some years – 2014, 2016 certainly – when we had a very good car. But we couldn’t really show it.

“We had a good double act with Sebastian Vettel and Mark Webber”

The car changed again in 2022. I think it’s a shame they have become so big and heavy. In our 20th year celebrations we had RB1 alongside RB20 – and RB1 now looks like a Formula 3 car. It seemed quite big at the time. F1 has always had a habit of popularising things in road cars. Now road cars are getting ever bigger and heavier as well, and in the drive to be green it’s the absolute opposite of what we should be doing. People can argue about where the energy should come from – battery, petrol or hydrogen – but the thing that is going to make it most green is using less energy and of course the bigger and heavier the car the more energy it’s going to use. Pretty simple stuff.

Newey still likes to use his drawing board when designing.

Personally I feel we need to be looking at making much smaller, lighter, aerodynamically efficient cars. Maybe if we did that it would help popularise a desire in the road car market to look at smaller, lighter cars too.

“We had RB1 alongside RB20 – and RB1 now looks like a Formula 3 car”

We’re facing another generational change in 2026. We know the rough principles of what the FIA is trying to achieve, which was initially a desire for a 50-50 combustion engine-electric mix. Whether that’s a good direction or not, it’s probably best I don’t comment. There is a drive to make the cars a bit lighter but the reality is it’s a heavy power unit, so there is only so far you can go. There is also a drive to make the cars more aerodynamically efficient, which I totally agree with and support. Unfortunately we suffer the same problem in motor sport as the industry: we end up working to a very prescribed and prescriptive set of regulations. In general, the drive is for zero tailpipe emissions by… well, whenever the moving target settles. It seems the wrong thing to me. This is the approach I’d prefer: we want to make the automobile less damaging to the planet, this is what you need to achieve, prescribe the make-up of the damage to the planet, set a broad set of limits and off you go – instead of zero tailpipe emissions which effectively means it’s either battery or hydrogen, neither of which currently reach the levels of performance we expect for grand prix racing’s format.

2005’s RB1 meets its oversized relation, this season’s RB20

If governments insist on zero emissions from tailpipes that doesn’t leave the internal combustion engine in a good place. But if you go for net zero that opens up all sorts of other possibilities. Biofuels and e-fuels are an interesting and growing concept. Whether that can ever be fully competitive on price is not clear. But as long as you insist on zero at the tailpipe you can’t do those things.

“If you go for net zero that opens up all sorts of other possibilities”

The FIA appears to be heavily influenced by one or two manufacturers, in the hope they will appease those manufacturers but also perhaps attract others in. I suppose since Audi are coming in for 2026 there has been a partial success in this regard, but I’m not sure it’s worth the overall compromise of what could be achieved. The reality is manufacturers come and go, with the exception of Ferrari. It’s the teams that are core to the business and then of course the big actual core is the viewing public. So it’s essential we provide a good show and as part of that variety is proven to be well rewarded. If you look at IndyCar, with a number of manufacturers involved up until the 1990s it was very popular, even starting to rival F1. It slipped into one-make and its popularity has gone down.

As for my own future, F1 still motivates me to get up in the morning. Starting from 2014 when we ended up in that demotivating position with the power unit, we looked at other projects that ultimately became the Aston Martin Valkyrie and the founding of Red Bull Advanced Technologies which now has several projects. The single largest one is the RB17 track car. So I’ve been dividing my time in the factory between that and F1. When I’m at race weekends I’m exclusively working on F1 and I find that useful in terms of what I can learn and bring back to the factory. That variety has helped me to stay motivated. I still get a buzz from races.

Red Bull domination continues… Max Verstappen is on course to match Vettel’s achievement of four world titles on the trot

You may ask is there anything left to achieve? Possibly not. Adding numbers is academic, but that has never been the motivation. The motivation really has been that I wanted to work as a designer in motor racing, ideally in F1 in some capacity, from the age of about 10. I’ve been lucky enough to do that and I still very much appreciate it.

In terms of what’s next, I’m not going to try and predict the future. I enjoy my time at Red Bull – being involved in it more or less from the start. How we have developed the engineering team, which does a fantastic job now, has been incredibly satisfying.

You may wonder why I don’t choose to become poacher turned gamekeeper and play a role in writing the rules myself. I’ve been asked many times. I’d need a complete change in the trend to over-legislate, which seems to be getting worse, not better.