An explosion of innovation: racing in the 1990s by David Richards

In the 1990s WRC became front-page news thanks to the Prodrive-run success of the Impreza. David Richards recalls heady times of innovation played to a Britpop soundtrack

Jayson Fong

I’m often asked what I consider to be the most interesting era of motor sport. It’s a tough question but for me it would have to be the 1990s. That’s the decade I found myself involved in three completely different activities: Formula 1, rallying and touring cars.

At Prodrive, we started off with the British Touring Car Championship and I was one of the original four people who established TOCA. To my mind the 1990s were the heyday of the BTCC, although others may think differently and of course the series is still going strong today. But we had proper budgets back then and developed really interesting cars: the BMW E30 M3s with the likes of Frank Sytner in the late 1980s and then at the end of what became the Super Touring era, the Ford Mondeos with Alain Menu winning the championship in one of our cars. It was a great period of creative engineering in those days.

The touring car scene became a worldwide phenomenon and wasn’t just about the UK as the 2-litre cars raced everywhere, including Australia. The BMW M3 was a truly global race car and that was where we cut our teeth in motor racing. Andy Rouse had his Ford Sierra RS500s with spectacular flames shooting out the back, but Ford were losing interest and we persuaded Andy that we should all change to normally aspirated, front- or rear-wheel-drive cars with a weight balance between the two. It was an interesting discussion as front-wheel-drive racing cars had never been taken seriously but that became a pivotal decision, and in the end everyone benefited. I don’t know what would have happened if we had not made that original TOCA agreement. As is so often the case it took a degree of compromise from everyone and I look back on it with great satisfaction.

Prodrive ran touring car programmes from the late ’80s into the 2000s, including Ford and its BTCC title-winning driver Alain Menu

For us at Prodrive, the next big thing was when Subaru came to us to go rallying. It was quite extraordinary to think about the impact a small manufacturer like that would make on the WRC. I remember telling the Japanese we’d win the world championship for them, but it was something they couldn’t comprehend against Ford, Toyota and Lancia as they didn’t think it was realistic. But the car was basically sound in its original design and we had a great team of engineers, spearheaded by David Lapworth, so in my view it was only a matter of time. Add to that the magic ingredient of Colin McRae and we created something very special.

Nearly 30 years later, I always remind people that Colin McRae winning the world championship in 1995 was on the front page of national newspapers. It’s hard to believe just how popular it was, with a million spectators heading into the forests to watch the RAC Rally.

That Subaru era still resonates today and there’s an enormous enthusiasm for the blue and yellow cars and of course the sound they made! I recall the managing director of Subaru’s importer saying to me, “Before Prodrive came along, we were selling pick-up trucks to farmers. Now we build high-performance cars for petrolheads.” The fact that we have recently produced a recreation of a car from that era, the P25, and sold them all overnight for half a million pounds apiece speaks volumes of the longevity and credibility of Subaru and what we achieved back then. Even today, they define the modern era of rallying for so many of us.

Richards had a solid relationship with Subaru president Ryuichiro Kuze, right – all smiles after the 1995 RAC Rally

We did have our fair share of luck, meeting some great people. Primary among them was Subaru’s Mr Kuze, who was always so supportive. He looked after the Japanese relationship while I managed the team and between us we had a wonderful rapport. Sometimes in life you find people with whom you have an innate empathy even though we came from two totally different cultures and were a generation apart. We just got on so well, he trusted me and I him, implicitly. He was the true father of that Subaru WRC programme and nobody else. And of course the programme didn’t stop at the end of the 1990s – it went on for many more years with Richard Burns and Petter Solberg winning further WRC titles.

Manufacturer investment was key to that era, right across the motor sport spectrum. Historically, and I saw it first-hand within Ford, motor sport had been funded from engineering R&D budgets, which is not surprising given the technologies it spawned. But what happened around that time was that manufacturers’ marketing departments began to understand the power of motor sport and it shifted from being technology driven to marketing driven. That is why so many manufactures came in during that period. They could see how motor sport could help to differentiate their product, whether it was on the racetrack or rally stage.

Audi led the way in the 1980s, virtually launching their brand on the back of their rally programme. Think what Audi was before 1981 – people hardly knew it. By the 1990s motor sport was seen as a very cost-effective way of manufacturers marketing their products.

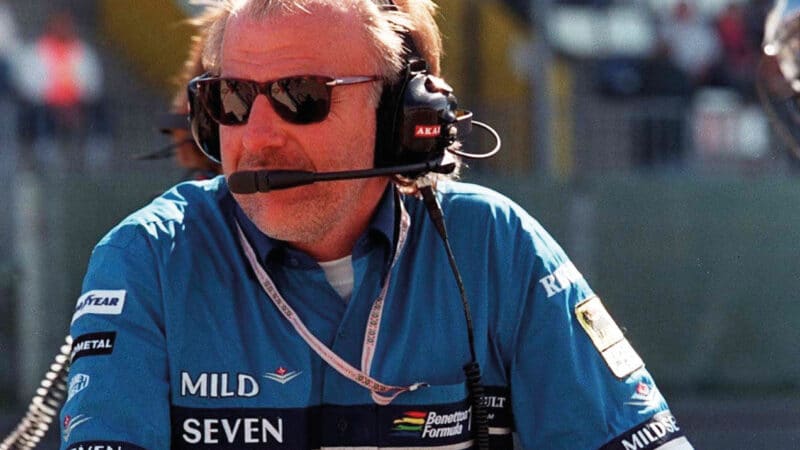

David Richards with his Formula 1 head on – at the 1997 Luxembourg Grand Prix with Benetton

Getty Images

Another aspect of that decade was the TV boom. It transformed motor sport, as it has so many other sports. Which leads me on to my F1 experience from that time.

I came in during a period of tension, the UK-based garagistes versus Ferrari and the FIA. F1 was still centred around huge personalities – Ron Dennis, Frank Williams and Eddie Jordan ran their own teams and had gone through difficult times to get to where they were. It was a strange situation to be parachuted into and suddenly find myself running the Benetton team at the end of 1997 among these extraordinary individuals.

“With BAR, I brought my own group of trusted lieutenants”

I suppose I was a forerunner of the team principals we have today, brought in from the outside to run an organisation, as Christian Horner was at Red Bull. I still remember my first race. It was the Luxembourg GP at the Nürburgring, and I walked into that paddock not knowing an awful lot about F1, to be honest. It was quite daunting and suddenly you are swamped by journalists and photographers. I thought, “What have I let myself in for?” I was a lone individual going into that team and when I first walked into the Benetton factory in Enstone, I didn’t know a soul there. I learnt a lot of lessons as a result of that. So the next time I went back into F1, with the BAR team a few years later, I brought with me my own small group of trusted lieutenants whom I knew well and we hit the ground running.

My F1 experience actually started with my relationship with the tobacco giant BAT and offers a good example of how big-name sponsors and car manufacturers thought they knew best when it came to motor sport. When we won the World Rally Championship with Subaru, BAT – which sponsored the campaign through its 555 brand – told me they wanted to get into F1. They asked if I would be interested in the project and of course the answer was yes. I went to see Bernie Ecclestone and at the time there were only four teams that had recently won a grand prix: Ferrari, Williams, McLaren and Benetton. The first three weren’t for sale, but in the case of the latter the timing was right for the Benetton family to exit. Michael Schumacher had moved on, they’d lost senior technical heads and with budgets increasing it was going to cost more to remain competitive. So after some negotiation we had a proposal whereby BAT could have bought half the company and then completed a sale over the following years. I put this proposal to BAT and was told that a cigarette business couldn’t partner with what they described as a “woolly jumper company” and that was the end of that, or so I thought. BAT decided to go their own way, buy the Tyrrell entry and essentially start from scratch. I must say I was disappointed because I thought we would have done a good job for them.

Jean Alesi, 1997 Luxembourg GP – Richards’ first F1 race with Benetton after Flavio Briatore’s departure

Getty Images

I then got a call from Bernie a couple of months later informing me that Luciano Benetton wanted to see me again about taking over the running of his team and bringing his younger son Rocco into the business. I headed to Treviso near Venice and over a weekend we came to an agreement over how I would run the team. It didn’t work out the way I expected, but you learn so many lessons in life!

At the end of that Benetton year in 1998 I had been to Dearborn for meetings at Ford and agreed a tentative offer from them to buy half the team from Benetton, bring the Ford engine along with funding but the Benetton family had other ideas and we went our separate ways. F1 was changing, from a period where you could run a team on a modest budget to one that required significant investment. Big sponsors were arriving and the whole picture was changing. I’m sure the family already had their eyes set on Renault, who bought the team a couple of years later. F1 was becoming a manufacturer’s playground.

Back then motor sport was still financed by tobacco, which is hard to believe now and I talk about it with a slight hesitation as to people’s reaction. But that was reality and it was just taken for granted. Then I watched their sponsorship quietly exit the sport and everyone was wondering how we were going to manage this transition into a new era without tobacco money. But world championship motor sport was well established by then and recognised as a great platform to market a wide range of products.

Recruited by BAR, Richards gave a seat to Jenson Button in 2003 as lead driver

Grand Prix Photo

We’ve seen this with Red Bull and many other companies that have become household names through their sponsorship activities. As far as the sport itself is concerned I’ve watched many categories go through transitions, their popularity going up and down, with F1 at the forefront today and the WRC currently out of favour. How long will that last? But history tells us that in motor sport nothing stands still for long and some categories of our sport don’t work in the modern era or are no longer attractive to an audience with so much choice.

One of the most striking things I’ve observed is the rapid advance of technology, particularly when it comes to computing power. I remember going into Benetton when they were building a very expensive new wind tunnel and I wasn’t totally convinced of its value for money compared with CFD. When I then went into BAR they had bought an expensive Cray supercomputer but we needed to ramp up our whole CFD capability. This time we did it with 100 PlayStations all wired together in an air-conditioned room as that was how fast technology had moved on; PlayStation had the best graphics chip.

The disappointment for me about motor sport of late is that we’ve lost so much of the innovation our engineers are so good at. We’re no longer seeing those cars that create those transformational moments: where Audi turns up with a four-wheel-drive car in the WRC, or some extraordinary development in F1 or a front-wheel-drive car wins a touring car race for the first time. That concerns me because we must be at the leading edge of technology to ensure our relevance.

As for the manufacturers, we know they don’t stick around for ever and we have to be clear about that. They are there for their own self-interest, not to make a charitable donation to motor sport. They are there to promote their products. When it doesn’t serve that purpose or represent value for money, or there’s a better way of communicating with their customers, they leave very quickly.

From left: Button, Richards and Jenson’s dad John after Button’s podium in the 2004 Bahrain GP

“At the end of the 1990s we emerged as a proper business that had substance and credibility”

So what am I most proud of? I’ve been asked that question many times as Prodrive celebrates its 40th year. The 1990s certainly did encapsulate a whole raft of extraordinary successes, in touring car racing where we were winning the British championship, into rallying where we were winning the world championship, and into F1 where we finally came good with BAR in the early 2000s. That decade was a coming of age for us. We were a small organisation at the start of the 1990s with around 200 people and with modest achievements but untold ambition. At the end of the decade we emerged as a proper business that had substance and credibility.

In terms of justifying our existence and how we carry on motor racing in years to come I have concerns. I’m far more aware of my responsibility to future generations than I ever was back then. Today I also wear the hat of a legislator of the sport in my role as chairman of Motorsport UK and sitting on the FIA World Motor Sport Council. Unless our sport is delivering technological benefits to society as a whole we will inevitably see a decline in interest and support. We have to bring technology back into motor sport, with new propulsion solutions, whether they be hydrogen, sustainable fuels or electricity. If we don’t we’ll stagnate and lose investment from manufacturers who have provided the lifeblood of our sport for so long.

Our technologies must be cutting edge and relevant and we must wake up to the environmental challenges of the world.