“The racers I knew…”by Wattie

I was fortunate to race with and against so many great characters in the 1970s, some of whom became close friends. I didn’t get to race in F1 for a full season until 1974, but clearly Jackie Stewart – who retired at the end of the previous year – was a giant of the era. Likewise Emerson Fittipaldi came in as a very young man, perhaps right place, right time, and won his first GP at Watkins Glen in 1970 and his first title in 1972 at 25. Emerson and I are within six months of each other in age. We were considered young back then, but Max Verstappen was 17 when he came in.

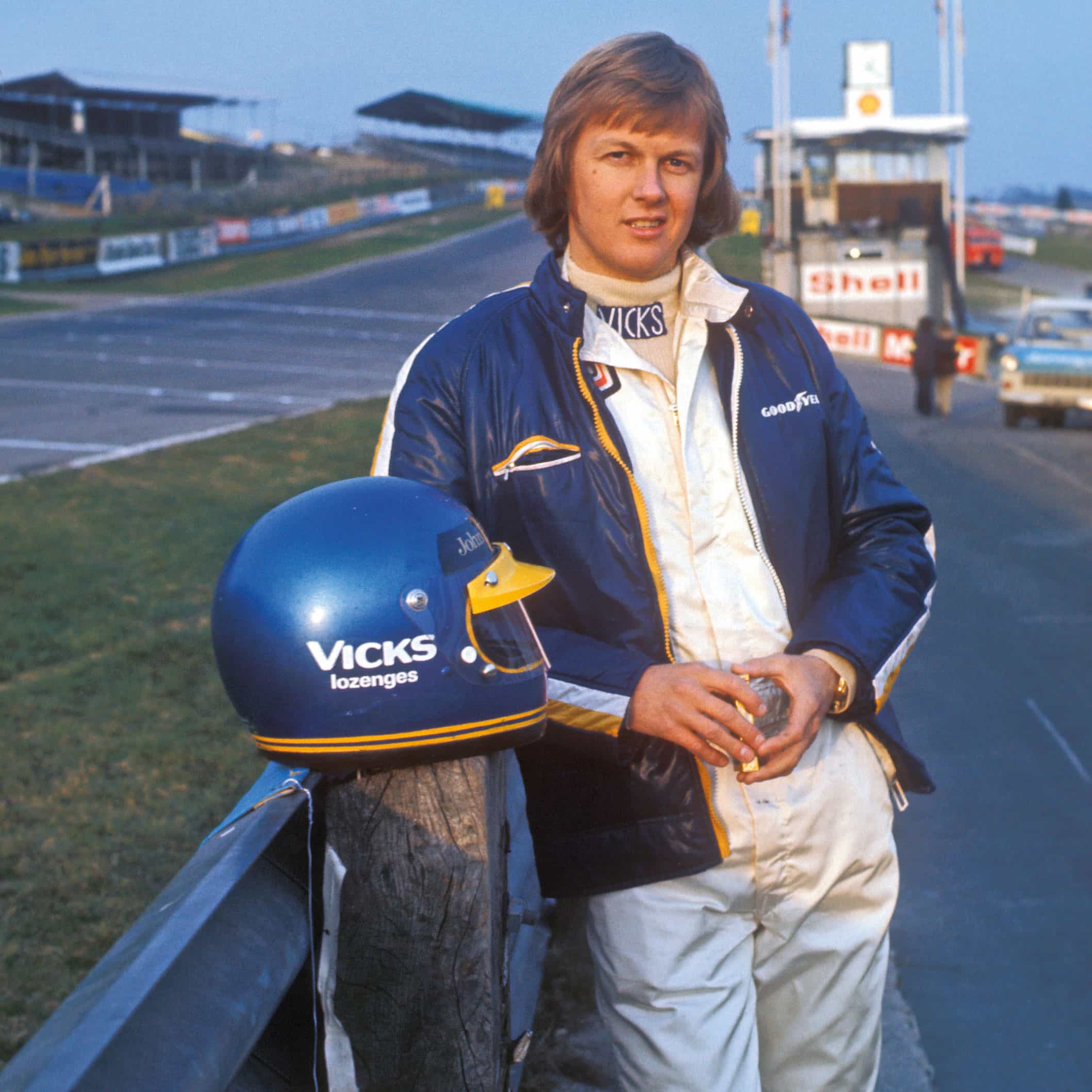

Ronnie Peterson

Ronnie first of all was a good friend. He was an exceptionally quick racing driver and one of his great skills was he could jump into anything and drive it quickly. He wasn’t as adept at developing a car. Ronnie’s skill was phenomenal car control, balance, natural speed, but most of all he was a genuinely lovely person. Lots of drivers have lost their lives and I’ve never been upset. But Ronnie’s death upset me. I still feel it now.

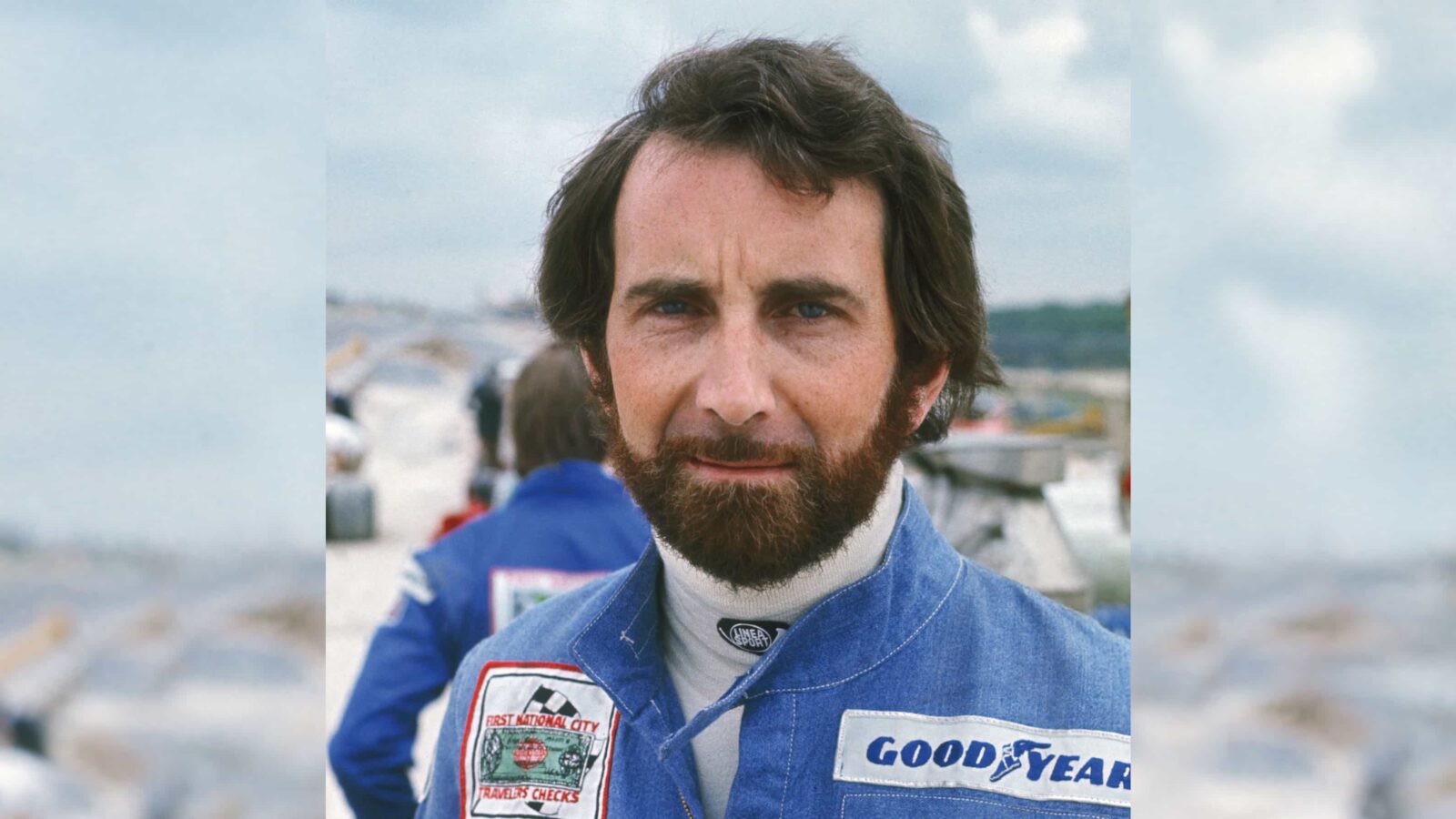

Jody Scheckter

James [Hunt] called him Jonathan Livingston Seagull, after a book which is an allegorical fable about a seagull with ambitions beyond flying and scavenging with the flock. I met Jody when he came across in the early 1970s and he was wild. A high level of driver ability. In 1973 at the French GP he and Fittipaldi had a collision. He was a loose cannon then, a little like Riccardo Patrese a few years later. But following Watkins Glen that year he was transformed after being one of the drivers who stopped at the scene of François Cevert’s fatal accident. What he saw had a seminal change on his outlook and philosophy of being a racing driver. He said later that it brought home to him that the sport he loved could kill. Jody wasn’t someone I had much to do with in the paddock, but I’m not sure he had much to do with anybody.

Bernie Ecclestone

He made a profound impact on me, not necessarily as a team leader, but he’s a pragmatic and lateral thinking person. Again, Watkins Glen in 1973 and Cevert’s accident… a wonderful, beautiful guy had lost his life and it felt disrespectful to jump back in the car and go back out. That’s what I believed, how I was brought up.

And Bernie said, “Get in that car, you’re here to race. Whatever happened to François it’s over and what you are doing is not going to make any difference.” It helped me throughout the rest of my career, when a driver was injured or killed. I was able to erect a kind of barrier around myself. It enabled me to put up a blinker to however awful or ugly it may have been, to get back into the car and race.

At Niki’s accident at the Nürburgring in 1976, I was one of the early cars through and I had him lying with his head on my thighs, looking into his face and comforting him as best I could. Then I had to jump back into my car and do a grand prix. I never gave it a second thought. That was the influence Bernie had on me, to detach emotion from what is your job. If you can’t do it, get out.

Later I had the same thing with Gilles Villeneuve at Zolder. I saw his body in the catch-fencing. I looked in his eyes and the lights had gone out. I got back in the car, drove back to the pits, told Teddy Mayer and John Hogan, and went for a coffee. Nothing. If a psychologist heard me say that, they would claim there is something wrong with me, to have that level of detachment. But soldiers, firefighters, the police – they need such mechanisms. You have to find what works best for you. That was Bernie’s influence on me.

Niki Lauda

The Niki of the 1970s was very driven, very focused and very ambitious. He had a vision of where he wanted to be and how to get there. When he drove for March initially it wasn’t a particularly good car, then he jumped ship to BRM and did an extremely good job. Monaco in 1973, he was outstanding. But he saw through Louis Stanley and realised the team was essentially going nowhere.

He needed to move on to a better place, and he’d done enough to attract Ferrari’s interest. He formed relationships with key people in teams who become ‘your’ people. He did that with Mauro Forghieri and Luca di Montezemolo and might have won the world title in 1974, but was going through a process of learning how to get there. By 1975, with the car he then had, he had done all his learning.

James Hunt

James was a pure animal, a pure athlete.

He turned out to have a lot of skill, probably against many people’s expectations. I saw him first in 1973 in the March at Monaco where he did a brilliant job. He was a bit of a contradiction in many respects because he seemed to have all the ability and skill, and a huge amount of intelligence as well which is fundamental. He was also a caged animal that needed to be controlled and some teams, principally McLaren, saw how to do that, holding him back and then lighting the blue touch paper and letting him go.

What Teddy Mayer realised in 1976 was, don’t let James screw around with the car, just get a good balance and throw rubber at it. James was like a lion trying to eat you alive. Bang, out he’d go and he’d deliver incredible laps. The other thing about James, in spite of his off-track behaviour, was he was a fit guy who played a lot of sports at a very high level as an amateur. He was mercurial in that second half of the 1976 season. OK, he had a very good car in a very good team, but he dragged out every last ounce of performance from that car.