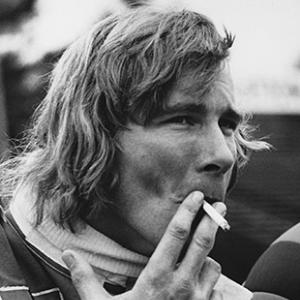

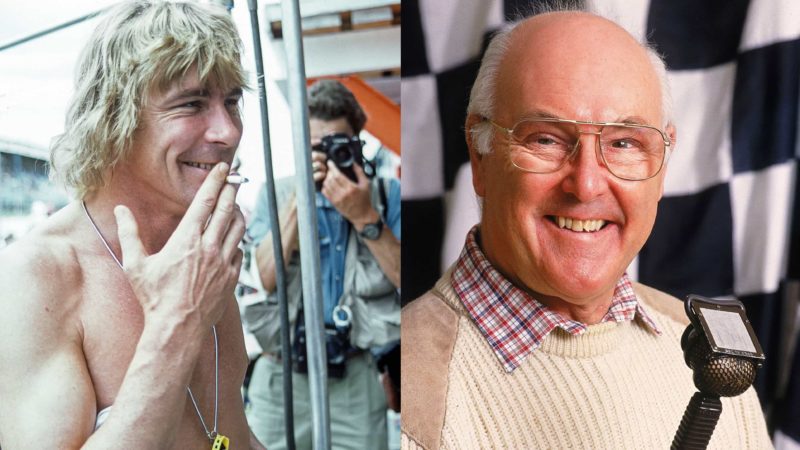

Murray Walker and James Hunt: F1 commentating’s odd couple

For those of a certain age, the commentary of Murray Walker and James Hunt was an essential element of summer Sundays. Mike Doodson was there and recalls how the double act took time to get off the grid

Getty Images

Although it’s 25 years since the television coverage of world championship grand prix races in Britain was purloined by a commercial network, many of the sport’s long-time fans will still fondly remember the previous BBC era with the distinctively strident voice of commentating stalwart Murray Walker, intermittently larded by the refined tones of his celebrity side-kick James Hunt. On summer Sunday afternoons, their banter would be the favoured soundtrack of households across the land.

“James arrived with his right leg in a cast from ankle to crutch”

The BBC’s guaranteed coverage of every race, previously a haphazard affair, cemented motor racing into the nation’s consciousness, alongside the classic bat and ball sports. The Beeb’s hegemony had begun in 1980, continuing for 18 full seasons, and though Hunt would fall victim to a heart attack at the age of just 45, Walker’s hold on the Formula 1 microphone endured well into the commercial era. For the entire BBC period I sat alongside him as his lap charter and spotter, until electronic technology –faster and more accurate than human eye and hand – cost me my job.

For reasons which we will see, Hunt would prove to be a controversial choice for the exalted position of co-commentator. However, it should not be overlooked that it was his own jousting with Niki Lauda for the world title throughout the nerve-jangling 1976 season that had ignited British interest in F1. Who better than he – a world champion just retired from the cockpit in 1979 – to bring expert insight to Walker’s commentary?

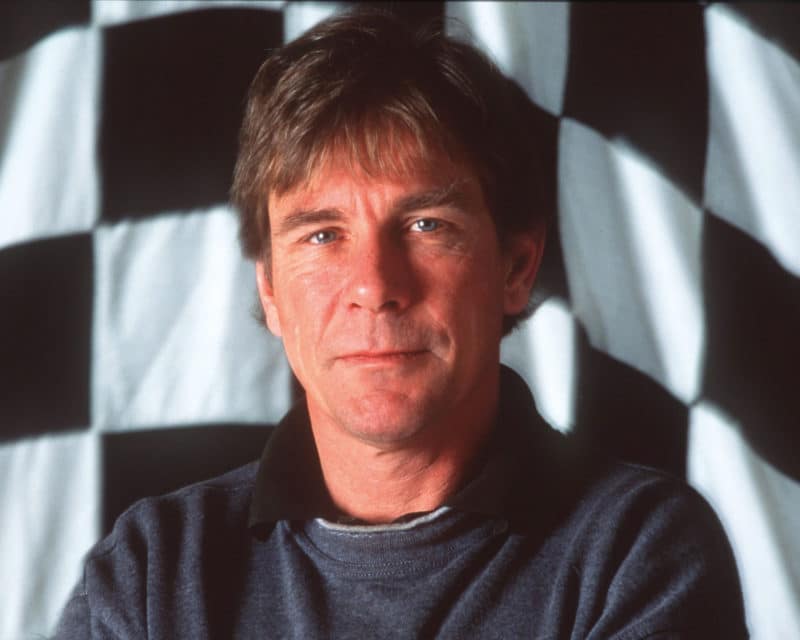

James Hunt retired from racing in 1979 and was quickly approached by Jonathan Martin, head of BBC TV sport.

Getty Images

That explained why the BBC wanted Hunt on-air, but it was a question which Walker, who initially feared that his co-commentator had been brought in to replace him, was himself asking at Monaco in 1980, only their second joint appearance at a race. He recalled: “James was still recovering from a skiing injury and he arrived in his frayed denim shorts, his shoeless feet, his right leg in a cast from ankle to crutch, and clasping a litre of rosé. I won’t go so far as to say he was drunk but he was, well, full.

“He then proceeds to put his plaster cast in my lap and get stuck into the rosé. God knows why, but our producer actually sent out for a second litre bottle halfway through the race. It all made for a pretty difficult situation. But James had the knack of surviving incidents like that.”

Early in their relationship, Hunt nicknamed his partner “Muddly Talker”. I don’t recall Walker being at all resentful. He knew that his style appealed to the public because the frantic delivery implied excitement, even when the racing got a bit predictable. In some ways he was also immensely professional. He would festoon the booth with scraps of paper on which he’d written down important statistics and reams of information, laboriously gathered over two days in the paddock. Back then, he would make half-hearted attempts to conceal the gems from his co-commentator rather than allow the long-haired slacker to benefit from them. This greatly amused Hunt, whose mental resources, not to mention certain prejudices, provided him with more than enough of the raw material on which he survived. As for Walker’s data, it goes without saying that the moments during commentary when he happened to be scanning his crib sheets somehow tended to coincide with moments when mayhem broke out on-screen, out of his vision.

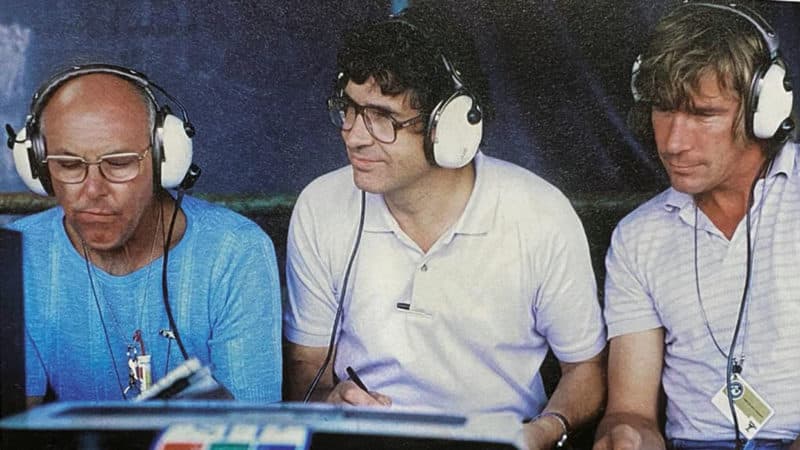

Hunt with Murray Walker at the 1986 German GP

If the oil-and-vinegar partnership with Hunt got off on the wrong foot, the resulting vinaigrette undoubtedly tickled the palates of their worldwide English-speaking audience. And though neither man would have admitted it at the time, each benefited from the other as they squabbled over the one microphone provided. Hunt needed the steadying, not to mention sobering, hand of the old pro. And Walker benefited from being the foil to Hunt spouting his strongly (and sometimes erroneously) held opinions alongside him.

Most remarkable was the fact that Walker, alone among the BBC’s army of expert sports presenters, felt unqualified to offer a value judgment on the drivers and teams whose competence he was being paid to assess. “I did not regard it as my right to criticise the drivers,” wrote Walker, evidently without irony; “James was fiercely condemnatory whenever he got the chance. With his knowledge and experience of what it was actually like to race a Formula 1 car he had every right to do so, although he was often vindictively unfair in my opinion.”

In any other televised sport, the holder of opinions which his fellows on the commentary team considered to be “vindictively unfair” would surely have come to the defence of the competitor under attack. Yet not once in my own years alongside Murray Walker in the commentary box did I ever hear him do so, either on-air or when the microphones were switched off.

Mike Doodson, centre, worked alongside Walker and Hunt as a lap charter

Thus it was that Hunt’s comments went unchallenged. Perhaps the viewers were too busy steeling themselves for the next delicious dose of muddly talking to notice that they weren’t getting a balanced analysis of what was happening on their screens.

Walker’s one undisguised prejudice was his bias towards British drivers. This was noted by a former editor of mine, Phil Scott of Australia’s monthly Wheels magazine, who arrived at Monaco in 1984 to write an inside story on the BBC’s F1 operations. It would be a controversial and incident-packed weekend which should have provided Nigel Mansell with his first-ever F1 victory, in a downpour. History records that ‘Our Nige’ had unwisely kept his foot down after taking the lead (from Alain Prost, no less). His John Player Lotus lost traction on a slippery white line at Massenet and smashed into the barrier.

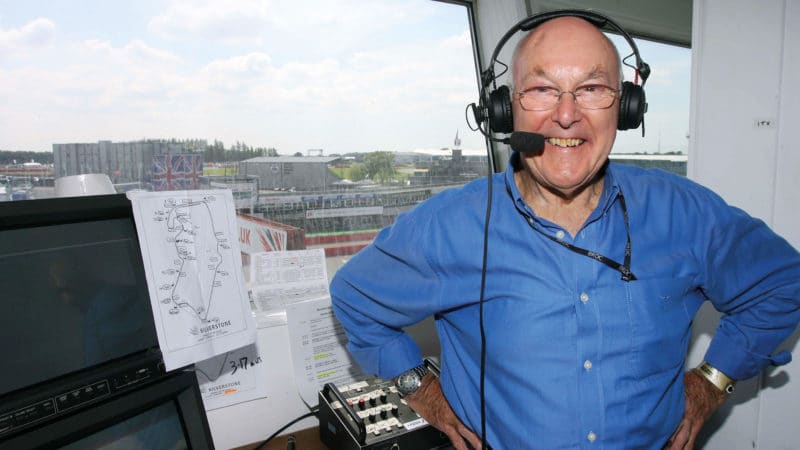

The Walker-Hunt double act lasted more than a decade – and they became good friends

As Scott wrote of the post-race confabulations, “Murray Walker interviews NM, then tells us that the JPS driver did a superb job. To me, it looked like he threw away a sure win. But I’m not British.” The Australian visitor was more impressed by Hunt’s verdict on the race, immediately after it ended with a prematurely-waved chequer (even though the rain was abating by then) and a narrow victory for Prost. “Hunt grabs the mic,” wrote Scott, “and quickly points out that it’s a straight French cheat.”

I never saw Hunt and Walker sitting down together to plan a co-operative approach to a race. More often than not, Hunt chose to stay in a different hotel, and on the occasions when he deigned to attend the pre-race days of a GP weekend, he would spend them confined to the Marlboro motorhome. This at least provided him with inside political updates and info about the brand’s own sponsored drivers.

“Hunt had an immutable catalogue of prejudices. One was against the French”

It baffled me that our masters at the Beeb were content to give Hunt free rein. He had an immutable catalogue of prejudices which he did not hesitate to express. One was against the French (as we have seen), and another against Riccardo Patrese, whom he held responsible for the events at Monza in 1978 that led to the death of his friend Ronnie Peterson. He also detested drivers whom he suspected of not trying hard enough, notably Nelson Piquet.

Hunt’s casual approach inevitably resulted in him quite often reacting to on-track incidents by damning the driver, who would subsequently be shown to have been blameless. He would then honourably make a point of searching out the innocent party at the next race to apologise and to offer a reassurance that he would do so again on air. On a couple of occasions, this required him to absolve Patrese, very publicly.

Hunt’s habit of arriving in the TV booth at the very last moment came to be expected of him at the Belgian GP, the date of which for several years coincided with his birthday. This was always an occasion for hard celebration. One year, he failed to appear at the circuit at all, although there were reports that on the Saturday evening he had been seen escorting two women to his quarters. Post-race he phoned the producer to claim that he had been brought down by a dose of food poisoning.

As different as chalk and cheese perhaps, but on air the commentary partnership – around one mic – was dynamite

Getty Images

That Belgian incident was probably the nadir of Hunt’s most dissolute period. If memory serves, it took place in 1989, around the time when his marriage to Sarah Lomax broke up under the intolerable stress which his behaviour had placed upon it. Suddenly, and now aware of his responsibility as the father of two small boys, he abandoned the mischief. As his friend and sponsor, Philip Morris/Marlboro’s John Hogan, marvelled: “he cut back on everything; the booze, the drugs, the cigarettes – even the womanising. His focus was phenomenal, which tells you how bad he had been when he couldn’t get out of it initially.”

Alas, the physical damage inflicted by such profound dissipation caught up with him only three years later, in 1993, when he died at home in Wimbledon as the result of a heart attack. At the service of thanksgiving for Hunt’s life, held in St James’s Piccadilly, one of the speakers who addressed the assembled mourners was Murray Walker.

In his autobiography Walker chose, for once, to make a personal value judgement. As he wrote: “at times [our association] had been stormy but it had worked extremely well, had given a lot of people a lot of pleasure and I was deluged with the most wonderful letters about it. Like all of us James was a mixture but at heart he was an endearing, good and honest man.”