Superbears: The Story of Hesketh Racing book review

Hesketh arrived to the pop of champagne corks, riling the F1 regulars, until… Gordon Cruickshank learns the ‘bear’ facts from a new book, backed by the team’s founder

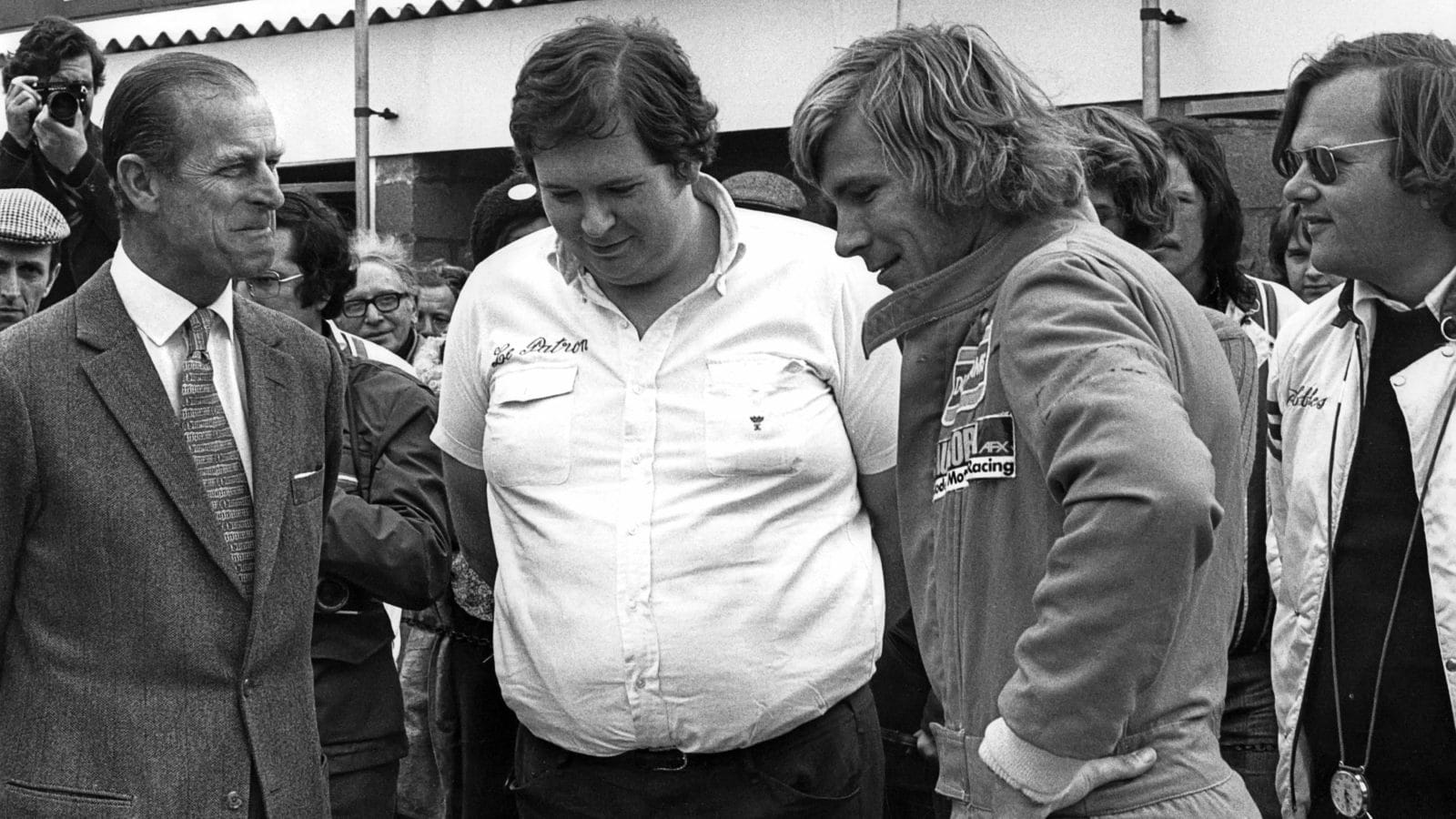

Prince Philip mixes with the bad boys of F1 at the 1975 British Grand Prix. From left: Lord Hesketh, James Hunt and Bubbles Horsley.

Getty Images

Couldn’t make it up? Of course you could, if you were writing an overblown novel: wealthy aristocrat backer, dashing driver coming from nowhere, yachts, champagne, parties, and then beating established names with a car they built themselves in the stables of a stately home. No one would really believe it – but it happened.

Superbears tells that story, backed by input from Lord Hesketh, co-conspirator Bubbles Horsley and many another, and it’s a great tale. Bunch of playboys messing with our sport, was the Establishment view and of some of the press too, until the team began to show results.

Of course, Hunt didn’t come from nowhere as the wider press implied. He’d been through the same struggles as all young drivers, through Formula Ford and Formula 3 where he’d shown enough talent to earn a March drive. But, said the man himself, “without Hesketh I was really on the way out in racing.”

Despite James Page’s outline of Hesketh’s privileged background, why he should believe so firmly his little team could produce a world champion is puzzling. Page makes it clear that Horsley was the racing enthusiast, already running his own team before he floated the bigger idea with his pal Hesketh, who says: “If Oulton Park hadn’t happened [Rothmans 50,000, 1972, when James was first F2 car home behind the F1s] I don’t think there would’ve been any further involvement by me in racing. I wasn’t addicted to it and I found it boring to watch.”

Even better is Page’s tale of a Goodwood test: “Alexander [Hesketh] soon got bored so he went for lunch at nearby Petworth House, only for the butler to come in and say he was needed back at Goodwood.” Hesketh also reflected that he loved Nürburgring “because you get 7min of peace”.

What riled the grown-ups when these champagne-fuelled reprobates pushed into Formula 1 was that the entire team seemed so casual about it. Ian Phillips in Autosport said, “The team has brought a breath of fresh air into racing. But where they score is that they are all happy and friendly, going about a serious occupation while the other teams go around poker-faced and miserable doing the same job.”

The team even published The Heavily Censored History of Hesketh Racing, a scrapbook showing off the helicopters, the yachts and the great house. Hesketh writes a funny foreword saying he’s not so much proud of the team’s achievements as the fact that “I have persuaded you to unload for this nonsensical publication”.

And how can you take seriously a team which lines up to cluck at The Great Chicken in the Sky? Hesketh again: “Max and Robin Herd got the humour, whereas Teddy Mayer at McLaren loathed us. We didn’t care, and the more we didn’t care the more he loathed us.”

They played up to it. Mechanic ‘Beaky’ Sims: “Lotus and March didn’t have mobile homes and big American estate cars and didn’t have butlers giving them champagne at seven in the morning.”

Harvey Postlethwaite’s 308, with Hunt aboard, reached the F1 grid in 1974, and opinions changed, other teams accepted them and the performance started to come, topped by winning the International Trophy at Silverstone, where James performed a stunning pass on Ronnie Peterson which confirmed to the world he was on his way.

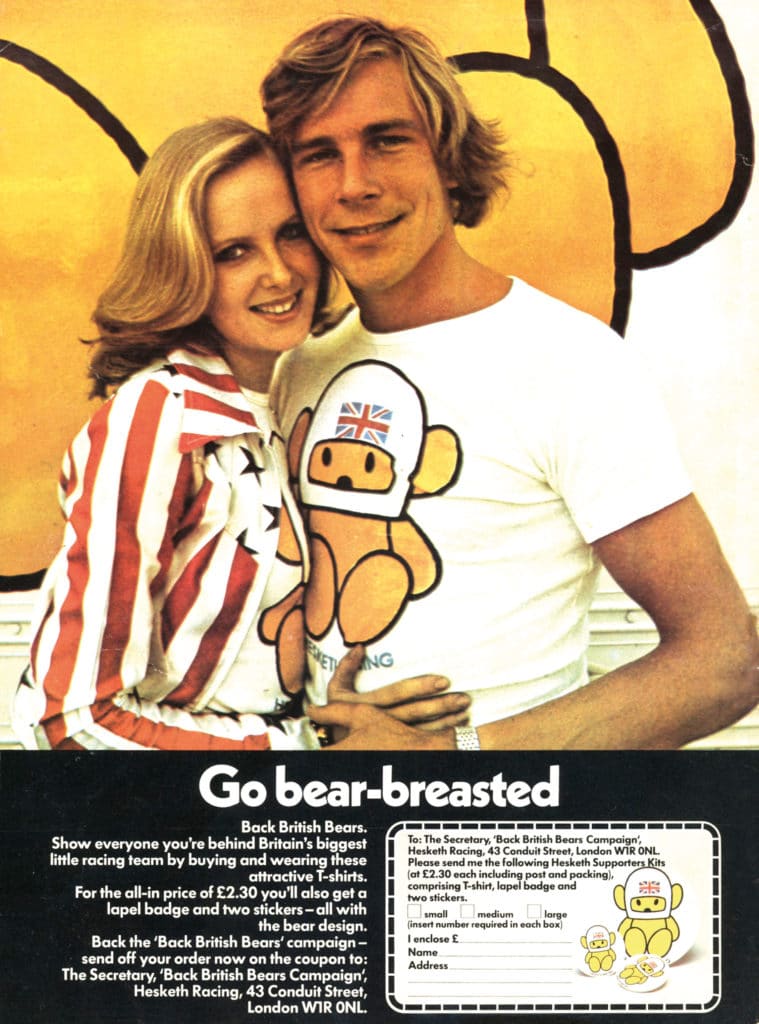

It was a gilded year for Hesketh: the Superbear logo was everywhere, press coverage was as lavish as the parties, the public loved them. Page points out that at Monaco in ’74 while the team fielded only one car, it had two yachts, with the chopper parked alongside.

Even champagne bubbles burst, though, and while 1975 brought that GP victory, at Zandvoort, the money was running out; the sponsorless team folded at the end of the year and Hunt went to McLaren, to be crowned as the team always predicted.

So much we know, and Page provides plenty of history and some great photos including many from Hesketh’s personal album and one of his lordship hanging out a pitboard with the instruction “In – Cocktails” when Charles Lucas is way ahead in a historic event in the team’s Maserati Birdcage.

Where this generous account really scores is its interviews. Hesketh and Horsley both talk with mild bitterness about their portrayal as Hooray Henrys born with silver spoons. None of them had, claims Hesketh. Hmm. Perhaps people have different definitions of silver spoons; the book makes clear that the glossy crowd who partied on the yachts were the people that Hesketh, Horsley et al would be socialising with in any case.

But all parties are firm about the professionalism behind the daftness. Hesketh reckons they spent more on wind-tunnel time than anyone else, and they had top talent in engineer Nigel Stroud and designer Postlethwaite. They even had an engine dyno; the gamekeeper was displeased because it disturbed the nesting pheasants.

In the end it was serendipity – rising star, wealthy owner and clever designer coming together in an era when you could buy race-winning engines off-the-shelf. And all without sponsorship to sully that white livery.

Surprisingly, I saw the barest reference to Hunt’s amorous activities and no mention at all of ‘the breakfast of champions’. Still, entertaining and informative, Superbears is everything you’d hope.

Superbears: The Story of Hesketh Racing

James Page

Porter Press, £89

ISBN 9781913089337