My friend Craig Breedlove, by Richard Noble

They were united as land speed record-breakers, and by a rivalry that crossed into friendship. Craig Breedlove never gave much attention to boundaries. Richard Noble pays tribute to the five-time record holder, who died in April

Breedlove in 1963

Getty Images

I first met Craig at Black Rock Desert when we were running Thrust2 in 1983. He kind of busted in on us when we were in a technical meeting in Bruno’s Country Club in Gerlach. We became great friends because we’d come up the same way, fighting the same sort of battles.

We were in trouble with Thrust2 because of the huge loads on the front axle; we had some 6000lb of static weight there and at around 629mph ‘Ackers’ [designer John Ackroyd] was getting very worried about the drag from the ruts we were digging, and that we might never get the record. Craig persuaded him to change the incidence of the car. But with no time for further wind-tunnel testing we just had to take a gamble. And it was a hell of a gamble because with slightly nose-up incidence as we reached transonic speeds around 630mph the download came off the front of the car far more quickly than we’d expected. In the end it worked out… just! But we were within about 8mph of flying.

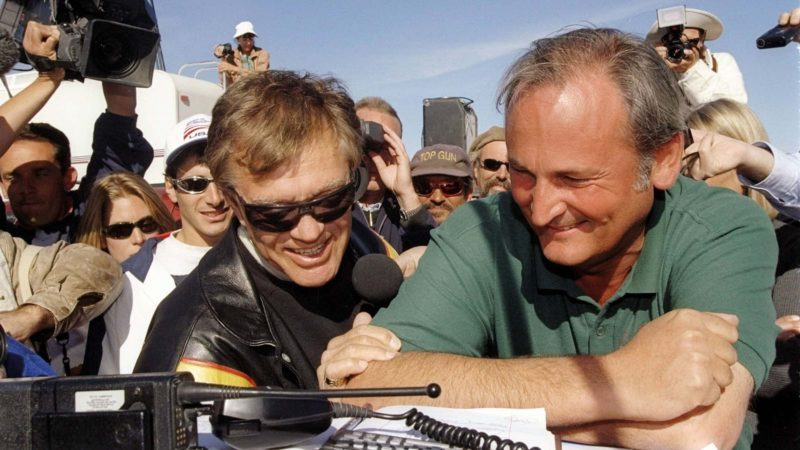

Craig Breedlove, middle, congratulates Richard Noble after ThrustSSC broke the sound barrier in 1997.

What I found fascinating about Craig was that he’d come up in the drag racing world. He’d gained experience building hot rods and then at 22 he was building his first jet car; that’s a fantastic thing to achieve at that age! We met up again at Bonneville in 1990. We were making a film about Art Arfons and Craig rolled up and he’d been in Utah buying jet engines. It was very nice to see him, and we all had a great evening together. And he took me to one side and said, “I’m building a new car,” and I suppose I was one of the very first ones to know. I said, “Craig, that’s great! What’s the plan?” He replied, “Oh well, in excess of 700mph. I’ve got two J79 8 series engines and I’m on my way.” Well, this was a wonderful thing to happen. I wanted to get back to breaking records again because as you know it’s the most exciting thing you can do on God’s earth! Trying just to break our Thrust2 record would have been seen as an ego trip, but a battle between the two of us – and at one stage McLaren was briefly a threat – could treble or quadruple the promotional value and help us both enormously.

“Craig had come up in the drag racing world, and at just 22 was building his first jet car”

We’d ring each other up every two or three months, and ask how the other was getting on. He was dead set on running at Bonneville, whereas we were committed to the Black Rock Desert because it had a better surface for cars with solid metal wheels. We’d learnt our lesson with them at Bonneville in 1982 but he designed these extraordinary wheels which were great in a sense because by filament winding a composite ‘tyre’ around an aluminium centre you hold the whole thing together. But salt erosion damaged the tyre and gave him tremendous balance problems. I went to see him a couple of times in the big pink building he had in Rio Vista, and it was fascinating because he hadn’t got a computer in the place. Now that could be seen as a criticism, but no way should it be. This guy had got much more experience with land speed records than any of us. And of course at that time we were always suspicious of computers. So, it was quite understandable. He was doing what he felt comfortable with.

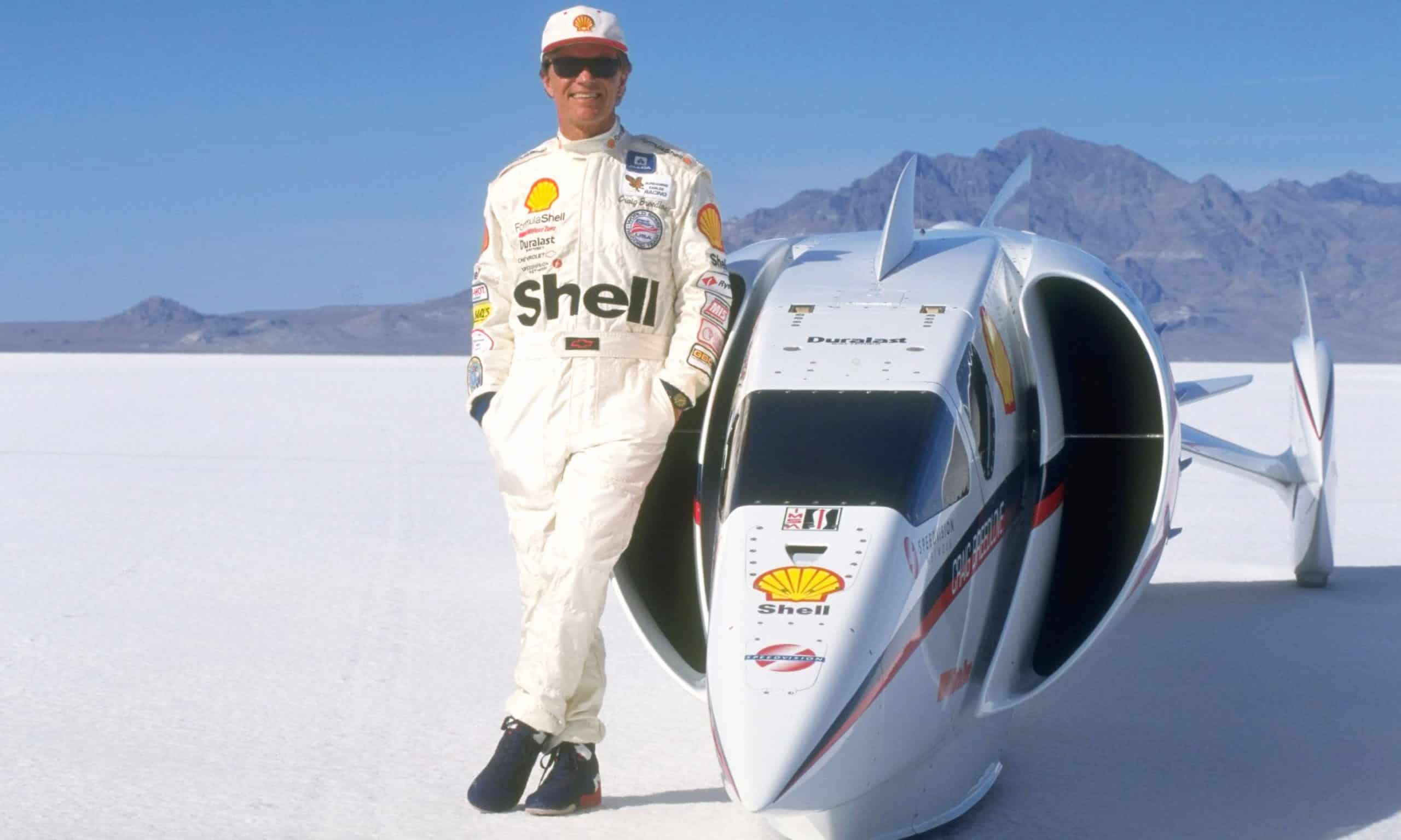

Breedlove with Spirit of America at Bonneville in 1964. His run of 526.28mph would make him the first man on land to top 500mph

Breedlove and Noble went head-to-head in 1997, with Spirit of America and ThrustSSC both vying for outright records

The same craft on Breedlove’s driveway in 1964

Getty Images

Because land speed rules are so minimal, the vehicles are completely different but, unlike F1, you can share information. Both sides didn’t even know that the other one would actually get there, or if their concept would actually work. That helped to build a great relationship.

Then in 1996 Craig had that extraordinary accident at Bonneville after we’d been testing on the Al Jafr Desert in Jordan, when Spirit of America – Sonic Arrow got on its side and did a U-turn at 675mph. The fundamental problem was both of us were moving out of our comfort zones. Thrust2 had been a transonic car designed to run to Mach 0.8, and that was the point where the air starts to go supersonic and the whole thing changes, big time. I’ve no idea what caused Craig’s accident, but the car rolled on to its right side and sort of hovered there. It’s absolutely extraordinary if you look at the footage. They claimed it was due to a 15-knot crosswind but the reality was that he’d got wings and wheel spats on that thing and probably there was a microscopic difference between the smoothness of each side of the car and the transonic shockwaves underneath tipped it up. The world’s fastest mathematician – Andy Green – calculated that Craig must have pulled at least 5g in that U-turn, so he was actually very lucky to survive that.

And, of course, Craig got out of the car and flew immediately to Las Vegas to talk to a Shell conference, having just wrecked his car. You’ve got to give the guy enormous points for his courage, you really have, and his sense of humour…

Breedlove at the wheel of Spirit of America.

Alamy

Spirit of America collided with a telegraph pole and came to rest in a lake shortly after breaking 500mph

Getty Images

Hitting 227mph on a 1997 test run at Black Rock Deser

One of the things that made him so special was that he combined three roles. He was the designer, the builder and the driver. That sort of thing scares me rigid because basically you can’t do all three roles properly, and there’s a real danger that you get something seriously wrong if you try and do that. And another difference between us, I think, was that I really enjoyed getting out there and driving, but though he would get into his car and do what he had to do, he told me he had these terrible dreams that he was going to die the next day, and awful trouble dealing with them.

Breedlove, left, and Noble scan the data during the record run at the Black Rock Desert in 1997

Getty Images

And it’s incredibly dangerous dealing with a transonic vehicle because it’s just not going to perform as you think it’s going to. He had no idea of how the transonic aerodynamics were going to behave with Sonic Arrow. He’d built this absolutely beautiful machine and I still remember when we arrived in September 1997 at Black Rock Desert with ThrustSSC how his team looked at us with absolute astonishment because they couldn’t believe what they were seeing. Ours wasn’t a traditional car in any way whatsoever. Somebody called Craig’s car the ‘Garden Roller’, whereas ThrustSSC was known as ‘The Binoculars’. They couldn’t understand that this was an active car with active suspension, and that we thought that was the only solution.

A lot of us on the Thrust team thought, “Thank God Craig actually stopped when he did there,” because we were afraid there could have been a really terrible accident. That U-turn must have really shocked the hell out of him, and I think he knew his design was compromised.

“When you gather, basically nobody knows what’s going to work and what isn’t”

Of course we had separate camps, and the interesting thing was that the American team was always in bed by 8pm whereas our team generally carried on until midnight. Though none of us had the time to socialise as such, because the workload on these things is so great, there was a friendly rivalry between us. Among the land speed record people, just as it had been when Donald Campbell, Mickey Thompson, Athol Graham, Nathan Ostich and Art Arfons gathered at Bonneville in 1960, basically nobody knows what’s going to work and what isn’t.

Sonic 1 in assembly

Getty Images

The English Leather Special was an early ’70s prototype rocket dragster

Focused in 1996

Getty Images

Craig encountered several problems, notably damaging an engine, and then he did an astonishing thing when we got to October 13 and Andy achieved 764mph on one run. We were encroaching on Craig’s allotted desert time, right towards the very end when it was quite clear we were knocking on the door of the sound barrier and had probably actually gone supersonic already in one direction. Booms had been heard in the mountains although the runs weren’t timed.

But winter was coming and we were out of money and some of our people were being called back by their employers, particularly the RAF guys. So we just had to keep going. And Craig said, “Give them the playa!” because he just knew he really wasn’t going to go any faster. It was an extraordinarily generous gesture.

The 39in aluminium wheels and tyres

Getty Images

Spirit of America – Sonic 1 at Bonneville in 1965. Breedlove peers through the tiny entrance hatch after hitting 595mph

Getty Images

And then, when Andy went supersonic at 763.035mph on October 15, to break our own 714.144mph record set in September, Craig was one of the first to come over and congratulate us. He was absolutely the gentleman, he really was. And we stood side by side experiencing this thing, and it was really great. And then several months later when we got our ThrustSSC book out, he bought a hell of a lot of them to send to all his friends.

Craig and I never had time just to go out drinking together. But I have a copy of his original book here and I discovered he’d written in the front of it: “To Richard, with my sincere gratitude, admiration and wishes for your continued success. Your friend, Craig.”

You move from one thing to another in life, don’t you? I should have made time to telephone him and just ask how he was. As it is, I will remember him as somebody who was still designing his 1000mph car right up until his last day, whom I admired enormously, and a good friend I didn’t spend enough time with.

Breedlove with Spirit of America model, 1964

Getty Images

Breedlove’s speed legacy

Some may have since gone quicker, but this is still some list

1937 Craig Breedlove is born.

1962 Constructs his first record attempt vehicle using a tricycle design powered by a J47 turbojet engine.

1963 Breedlove achieves 407.447mph to score his first record.

1964 With both Tom Green and Art Arfons challenging, Breedlove ups the record to 468.719mph. Then, just two days later, he achieves 526.227mph. His emergency parachute brake fails and the car slides through a series of telegraph poles and into a lake. Breedlove escapes injury.

1965 Spirit of America – Sonic 1 achieves 555.485mph for Breedlove’s fourth record. Two weeks later he improves to 594mph to set his final benchmark.

1997 Breedlove and Richard Noble compete for the record, but Breedlove loses out to ThrustSSC’s incredible 763.035mph.

2023 Breedlove dies at home in Rio Vista, California, due to cancer, aged 86.