Greensall reaches a racing milestone

PAUL RICARD, SEPTEMBER 5-7 Following three days of testing, it was time for more Peter Auto action, racing four cars with John Emberson: Morgan SLR; Chevron B26 Chocolate Drop (second…

You can wait a long time for a Le Mans-winning Group C Porsche to turn up – and then two arrive. Our writer is in test heaven at Goodwood

Mark Riccioni

These are none other than the first and last Porsches to win the Le Mans 24 Hours during the legendary Group C era. Not examples of those cars, but the actual cars. And this is the first time that Porsche has allowed them to be brought together and tested by a motor journalist. This, then, is quite an occasion.

But there’s more here, even than that. You might expect two such famous racing cars to be grizzled warriors, veterans of dozens of fights that took place all over the world during the superb first six years of the Group C era. But they are not. In fact their race records are staggeringly short: for Porsche 956-002 did Le Mans in 1982 and, apart from one demonstration run by Derek Bell the following year, was then frozen in aspic for the next four decades. By comparison Porsche 962-006 was only a little busier: It did the Spa 1000Kms in 1986, where Bob Wollek and Jochen Mass were delayed by a puncture. It did the Fuji 1000Kms later that year where it retired with a transmission fault, then it did Le Mans in 1987 which it won. And that was that. Two cars with a grand total of four races and zero accidents between them.

Which means that what you see now, really, is what won Le Mans then. Had they done dozens of races thereafter, they’d have been pulled apart dozens of times too, gained engines, gearboxes, bits of bodywork and who knows what else that they’d never have had at their moment of greatest glory. But both cars won Le Mans and never raced again, which means they are time capsules.

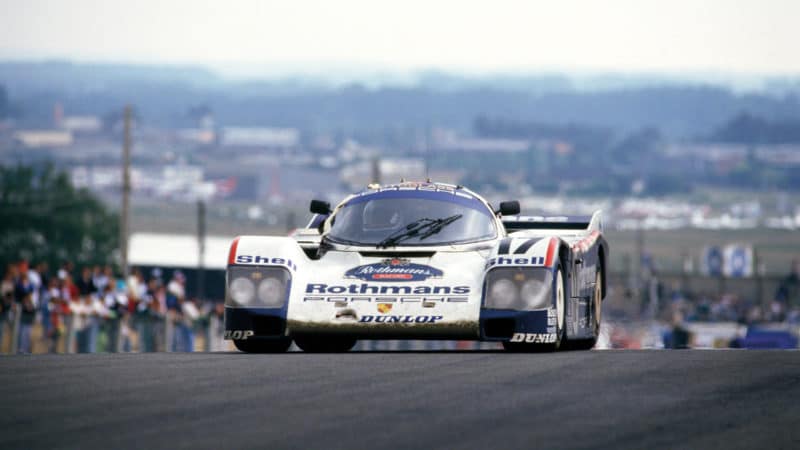

How then is it that both appear perfectly preserved, with none of the physical evidence that would inevitably accrue on their surfaces after 24 hours of battle? For the 956, because it was going to the museum, it was decreed it needed to be visually perfect, so its blemishes were removed. For the 962 it was prepared for Le Mans in 1988, and therefore wore Shell Dunlop colours, but it sat out the show as the T-car before being returned to its classic Rothmans livery.

We had them to ourselves for three days straight, during which I drove both on the Goodwood race track and up the Goodwood hill. We finished with me driving the 962C in a high-speed demonstration with 17 other Group C Porsches on the Saturday evening of the 79th Goodwood Members’ Meeting. I will never forget it.

But for now, we should look at these cars and how they got to be that way. And perhaps the first thing to mention is that many of us who are today old enough to remember the 1982 introduction of Group C didn’t think it a good idea at all. The slim regulation book was encouraging, but its key edict was not: no car could use more than 600 litres of fuel in a 1000km race, or 2600 litres in a 24-hour race. It was a fuel consumption formula, destined to turn the top tier of sports car racing into an economy run. Wasn’t it?

The only good thing was Porsche seemed singularly ill-suited to the new regime. Good? Because it had already won half the Le Mans 24 Hours held in the previous dozen years. It had in that time alone overtaken Bentley, Ford and Jaguar’s total scores in the race leaving just Ferrari’s total of nine to beat, and the Scuderia hadn’t won there in 17 years. Porsche had been the dominant force in sports car racing but now it would require something genuinely extraordinary for Group C not to end that era.

The podium at Le Mans in 1982 was an all Porsche affair, with 956-002 giving Jacky Ickx his sixth win

Mark Riccioni

The problems that faced Porsche were numerous and serious. The fact it had never designed a ground-effect car was one that was common to most manufacturers looking to join the new formula. But Porsche was doubly disadvantaged by the fact it had neither the time nor the money to develop the 120-degree V6 it wanted for the new car, so would have to rely on its old flat six. But as Ferrari had found out two seasons earlier when its flat-12 312T5 plunged the team from championship winners to failing to qualify when ground effect really got going in F1, a flat formation engine is just about the last thing you want getting in the way of your underbody ground effect aerodynamics.

And that engine would have to provide big power for its size because Porsche didn’t have the luxury enjoyed by the likes of Mercedes-Benz which had a 5-litre V8 it could turbocharge and slot in the back of its contender. But perhaps the biggest and most surprising of all was that for all Porsche had achieved in racing and despite the fact that Jaguar had first done so in the 1950s and Lola in the 1960s, it had never designed a monocoque race car, a construction method the Group C regulation demanded.

With those financial constraints, the 956 came to the grid with the same 2.65-litre twin turbo motor used to win Le Mans the previous year in the spaceframe 936 (which itself had literally been removed from the museum to do the race) and which had actually been designed for an earlier stillborn IndyCar programme.

The 956’s 2.65-litre flat six had been used at Le Mans in 1981 – powering Ickx and Derek Bell to victory.

Mark Riccioni

Mark Riccioni

Mark Riccioni

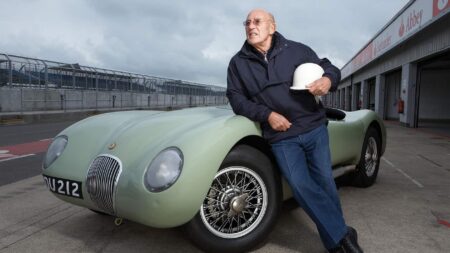

For Norbert Singer, the man who would more than any other be responsible for the 956 and 962’s utter domination of sports car racing, it was the chance of a lifetime and the results spoke for themselves. “Of all the cars we made,” he told me, “this was the one that was the most successful and over the longest period. It is my favourite.”

While others saw the problems inherent in the new formula, Singer saw opportunity. “It was great. It was a new challenge. We’d always tried to make cars with the minimum weight, maximum power and best aerodynamics and while that was never boring, it’s all we’d ever done. And now with having to take fuel consumption into account, it was suddenly very interesting.”

Jonathan Palmer told me that what he most liked about Group C was that it was an engineer’s formula and that the team with the smartest brains behind it would always do best. But so great a leap did the 956 represent over the 936 it replaced, that the limiting factor at first were its drivers.

“I did some lap simulations in the car and realised that it would be quite fast,” explained Norbert, “but not even Jacky [Ickx] could get close to those times at first. It took some months until we did at test at Paul Ricard and suddenly him and Derek were going around three seconds a lap quicker in the same car, and we hadn’t touched it! They’d just got used to the downforce.”

Ickx at La Sarthe, ’82

The car was also prepared in astonishingly quick time. Six months before Le Mans 1982, not a single 956 had been built. Three months before not one had even run. Yet come the big day there were three 956s on the grid and, 24 hours later, three on the podium too. It ushered in an era of almost mind-boggling success: it was the first of six Le Mans victories in a row, and contributed to the first of five World Sportscar Championships. Across the Atlantic, the 962 won the Daytona 24 Hours three times in succession, and netted a hat-trick of IMSA titles on the way. And those are just the headlines.

“The reason it lasted so long is simple,” Ickx once told me. “When it was new it was so far ahead of its time it took years for others just to catch up. Meanwhile Porsche continually developed the car to keep it ahead. I can remember when I first drove it thinking ‘this is special’ but I didn’t realise how special it was.”

And that’s the point. Once Porsche had got its advantage, it didn’t squander it. It pushed on relentlessly, developing the car, keeping ahead of the opposition until finally the fundamental age of its design and the inherent weakness of its aluminium monocoque was exposed by the new era of carbon tubs like those sported by arch-rival Jaguar. But by then its legacy had already been long secured.

| Porsche 956 |

| Power 620bhp Engine 2.65-litre six-cylinder boxer turbo Weight 850kg Top speed 224mph |

I approach the 956 as you might an unexploded bomb. The car is unique, so valuable and precious I fear that one false move on my part is all that would be required for disaster to unfold. By contrast, the team from the museum who look after it are completely relaxed. You can’t stand or rest any part of yourself on the door sill, otherwise, it is completely robust. So I swing myself into it and down into a tiny cockpit.

To me the outside still looks modern and beautiful, but in here, frankly, it’s all a bit of a mess. There are buttons, switches and dials I recognise from period 911 road cars, bits of Dymo tape labelling gauges, a leatherbound Momo wheel with a radio transmit button attached and nothing else. I can see where the edges of that wheel have been worn smooth and discoloured by Jacky and Derek’s gloves as they wrestled with this car for a day and night to bring it home at an average speed including all stops of over 126mph. Makes you think, doesn’t it?

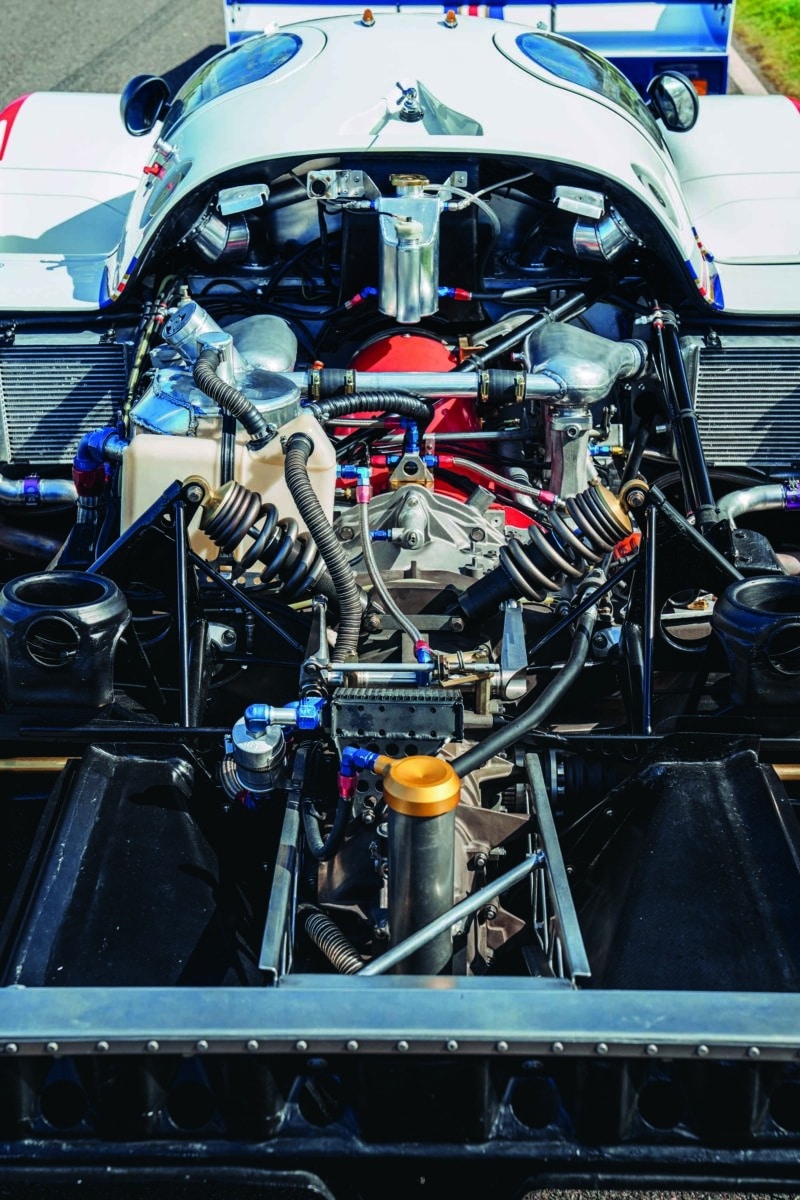

The start procedure could scarcely be more simple: turn the key. You don’t even need to press a button. Keep your foot off the throttle and wait for the flat six to burst angrily into life. Which it does, and then idles as easily (albeit rather more noisily) as a 911 SC. The big difference between this engine and that of even a 911 Turbo of this age is that the race motor needed greater efficiency than could be achieved with single cam, two-valve heads, but it would not be possible to use a twin cam, four-valve layout with air-cooling, so this Porsche is cooled by both air and water, the former for the block, the latter for the heads. It’s capable of producing around 650bhp, which was already probably slightly more than the rule makers had envisaged.

The gearbox has five speeds, laid out in a conventional racing pattern with first back and towards you, and in traditional Porsche racing practice, it also has synchromesh. This means the box is a little heavier and the change a little slower, but Porsche deemed that small price to pay compared to the number of retirements suffered by rivals with uncompromising dog boxes. First requires a healthy tug on the lever, and like all the other controls the clutch is heavy, but the motor sufficiently tractable to allow a smooth getaway. And there you are, driving the 1982 Le Mans winner around Goodwood.

It’s obviously not a track where Group C cars ever competed, but with its long, flowing high speed corners it’s a natural fit for such a car, though you’d want Porsche’s short-tail high downforce bodywork for racing. And once you’ve got a feel for the way the controls want to work, the car is utterly reassuring from the outset. Unlike a Jaguar Group C car, which needs watching both while braking into and accelerating away from corners, the 956 seems instantly on your side. You feel everything through the steering which writhes gently around in your hands while it lets you pick your apexes with pinpoint accuracy. The overall gearing is high which means that first is actually a proper gear which might even have been used for maximum thrust away from Arnage or Mulsanne, while fifth will take you to 230mph and beyond.

Derek Bell describes the 956 as “utterly viceless, a car that rewarded the professional driver by being the quickest car out there and the amateur by being so forgiving on the limit. Porsche understood better than anyone that it was not enough for the car just to be fast: it had to be fast for 24 hours, regardless of the talent of the man behind the wheel or how tired he was. Which meant it had to be easy to drive.”

But the engine, despite its water-cooled, multi-valve heads, still feels decidedly old school. With a compression ratio of something like 7.0:1, it’s lethargic off boost, with the power arriving in a single shot somewhere between 3000-4000rpm, hurling you down the curving straight towards St Mary’s at a simply staggering velocity. A glimpse, and no more than that, of what Messrs Bell and Ickx experienced at Le Mans 40 years ago hoves into view. And you think: two drivers, unassisted steering, heavy controls, zero air-conditioning, 54 other cars on the same track, night time, rain… and you conclude these people are supermen, for there is no other rational explanation for what they did, not as a one-time, never-to-be-repeated all-out win-or-bust bid for glory, but part of their every day job.

And they kept on doing it, in Bell’s case as the only driver the factory retained from the very start of its Group C adventure in 1982 to the very end in 1988 where, having already collected an unprecedented succession of seven straight wins at Le Mans, it failed by minutes to collect an eighth. So that last win came in 1987 with chassis 962-006, and on first inspection you might think there was little difference between the two machines. And in one sense they are very similar, in others really rather different.

| Porsche 962C |

| Power 700bhp Engine 3-litre six-cylinder boxer biturbo Weight 850kg Top speed 224mph |

We’ll deal with the red herring. The 962 may have had a new name, but it was not a new car. It wasn’t created to win Le Mans, but as a direct response to IMSA banning the 956 because it placed the driver’s feet ahead of the front axle line. The 962 was a long wheelbase 956 with what was added between the axles removed from ahead of the front wheels, which is why it looks more snub-nosed and less graceful than a 956. The 962 made its US debut in 1984 and when IMSA safety standards were adopted for the World Sportscar Championship the next year, the 956 was replaced by the 962C for customer and factory teams alike.

It was the other changes, those that were less easy to see, that really upped the pace and potential of first the 956 and

the 962. The first big change came late in 1982 when fully electronic Bosch Motronic engine management was introduced, bringing ignition and fuelling together under one system. This, combined with ever increasing compression ratios, rising from 7.0:1 to 9.0:1 between 1982-87, meant not just more power but, just as important, greater fuel efficiency. So they could not just go faster but, crucially, do so for longer on the limited fuel allowance.

orsche 962-006 carried a Shell/Dunlop livery at Le Mans a year after its crowning glory, but was only used in practice

Mark Riccioni

Likewise the aerodynamics. Look at these two for long enough and you’ll realise they don’t share a single panel. “Porsche were never one to rest on their laurels, even when they were winning everything,” says Bell. “They never stopped tinkering.”

The engine itself grew in size, with a new 3-litre, fully water-cooled motor introduced for the 1987 season which not only used less fuel than the 956 engine, it also had 750bhp, at least 100bhp more than the 956 motor. A special qualifying engine for the 1988 race was reputed to put out over 850bhp.

How much faster was a factory 962 than a 956? Well a simple comparison of Le Mans pole times revealed the 962C in 1987 was 7.3sec a lap quicker than the 956 had managed in 1982 which perhaps isn’t that extraordinary given natural development over a five-year period. Until, that is, you consider that the 1987 lap time was done after the installation of the slow chicane before the Dunlop Bridge, requiring drivers to shed and then regain something close to 100mph. Then it is astonishing.

It’s testament to Porsche designer Norbert Singer that the 962 still looks modern…

Mark Riccioni

Mark Riccioni

Usually at the Porsche Museum in Stuttgart, 962-006 is a regular visitor to Goodwood

Mark Riccioni

I’m more comfortable inside the 962C, not because of the longer wheelbase, but because the lanky Hans Stuck joined Derek Bell and Al Holbert in this car for Le Mans in 1987 and his seat is still in it. The dash has changed a bit: there are a couple of small digital displays where you can call up information via one of three rotary dials, the others adjusting mixture and boost. But it’s still very familiar. The start procedure is the same, the pedals feel the same as does the gearbox. I’m told that today the car is running at around 660bhp, a long way off maximum boost but probably close to what you’d use for long-distance race pace.

And what does that feel like? Well if I tell you its power-to-weight ratio even in this trim is more than twice that of Porsche’s current sports car flagship, the 911 Turbo S, you will appreciate that here is a car that will accelerate in a manner that even those experienced with some of the fastest supercars could even conceive.

The book is an examination of every angle of the 962 story in exhaustive detail

Mark Riccioni

Mark Riccioni

Mark Riccioni

Yet for all its extra power, it has less lag and a more progressive power delivery than the 956, for which you can thank Motronic, the extra cubic capacity and higher compression ratio. It builds, quite gently at first. Between 3000rpm to perhaps 4500rpm it’s going nicely, accelerating like a rather healthy hypercar. But then it lunges into a different dimension of performance, one which makes your stomach feel hollow and your legs go weak. Although no one asked me to, I changed at 7200rpm out of respect though the line on the dial says 8400rpm, at which point I’m sure it would still be pouring on the power.

We had 15 minutes for the demonstration, enough for perhaps nine laps of Goodwood, probably less than a third of a stint at Le Mans. I tried to imagine, tried to relax into the car, forget its importance and value and make like Derek or Jacky in France. And of course it’s not possible because, apart from anything else, we weren’t allowed to overtake and had to follow a course car, which in this case was a 911 GT3 going as fast as a skilled driver could make it go, but which by 962 standards wasn’t fast at all. I hung back, created as big a gap as I dared and then went for it until I caught the back of the Group C train again. And it was enough to feel the bodywork start to generate some downforce, enough to put some loading in the suspension, enough to gun that incredible motor through the gears until I saw 6000rpm in fifth. I don’t know how fast that was; probably not fast by 962C standards, but by Goodwood standards it felt like it was flying.

A dream assignment for our writer, at the rear of a Porsche Group C cavalcade at Goodwood’s 79th Members’ Meeting in April

Mark Riccioni

Honking around the back of the circuit with the sun dipping and the headlights of a grid-full of Group C Porsches piercing the night ahead of me was as close to a romantic experience as I’ve had on a track. It was magical, not just to be in that car, but to see the greatest collection of the greatest sports racing cars made by the greatest manufacturer of such cars ever seen in action in one place.

And then it was over and 956-002 and 962-006 were back under their awnings. Will it happen again? Perhaps for the 50th anniversary in ten years’ time, if such celebrations are even allowed by then. If not the spectacle provided those who were there to see it with a memory to last a lifetime.

PAUL RICARD, SEPTEMBER 5-7 Following three days of testing, it was time for more Peter Auto action, racing four cars with John Emberson: Morgan SLR; Chevron B26 Chocolate Drop (second…

In the end, it is just a car. You sit with a steering wheel in your hands. You change gear by shifting a lever fore and aft, working your way…

Okay, so the contract for 1994 may not be in the post, but when I got the chance to drive the championship-winning Williams I really wanted to make a good…

This is as much a tale of two people as two cars, and despite the images on these pages, neither of them is called Bentley. If two cars ever came…

Have you ever driven a Ferrari Challenge car before?” enquires a thickly Italian-accented voice from behind a full-face helmet. The man speaking is none other than Giampiero Simoni, a legend…

PHOTOGRAPHY: Dean Smith Well this was going to be a first. I’ve been track testing cars for this title for 28 years and can recall just one occasion on which…

John Watson loved his Chevron sports car cameo. Especially his dalliance with this, the 2-litre B26 known universally as ‘Chocolate Drop’. Bizarrely, it was the second of two brown racing…

The true value of most great technological breakthroughs can usually only be appreciated with the benefit of hindsight. Life didn’t change the moment Karl Benz first swung his Motorwagen into…

The back straight is quite short, but we’re already running out of revs in top gear. The 100-year-old car is now in a proper hurtle, engine bellowing, tyres singing their…

Reynard in a Reynard? This we’ve got to see. Especially as the car in question is peak Formula 3000, the long-defunct Formula 1 feeder that roamed Europe as a gloriously…

“Okay. But please ask the announcer to tell the crowd why I’m not waving.” Sir Stirling Moss – the original professional racing driver and at the age of 80 still…

These are none other than the first and last Porsches to win the Le Mans 24 Hours during the legendary Group C era. Not examples of those cars, but the…