1952 Le Mans 24 Hours: only Mercedes had luck left in the tank

Study the results of the 1952 Le Mans 24 Hours and the Mercedes 1-2, achieved with the new W194, suggests a shift in power to Germany. As Andrew Frankel reveals the reality was different, and the gullwings were not fast. This was a war of attrition packed with tactical nous, derring-do and a great deal of luck

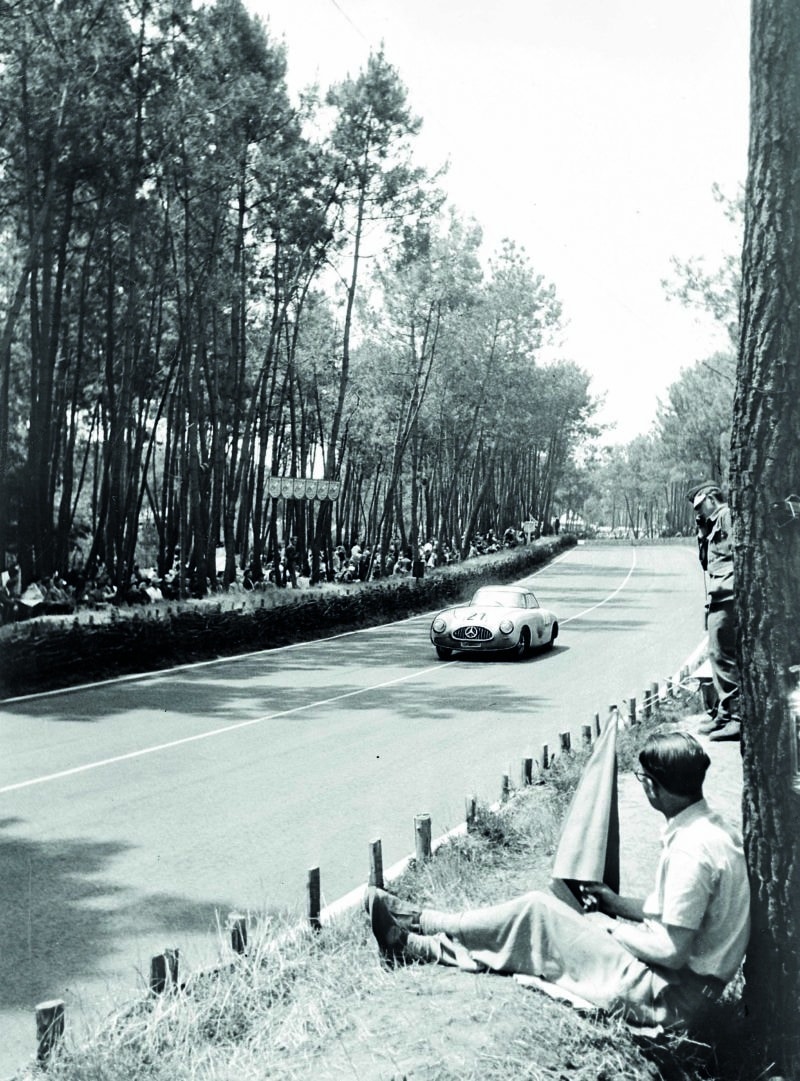

The race is underway... The crew of the Mercedes W194s were Karl Kling/Hans Klenk (No20); Hermann Lang/Fritz Riess (21); and Theo Helfrich/ Helmut Niedermayr (22)

Mercedes-Benz

The key players came from all points of the compass. From the south the Ferraris; seven of them, including four monster 340 Americas with their 4.1-litre V12 motors. Soon-to-be F1 world champion Alberto Ascari was there too, in the same 250 S in which Giovanni Bracco had heroically taken on the might of the works Mercedes-Benz team in the Mille Miglia just weeks earlier and, subsisting on a diet of brandy and cigarettes, prevailed. Of the Mercs, more in a moment…

From the west came the Americans or, to be precise, an American. Briggs Cunningham and his fleet of three C4-R racers, two open, one closed, with over 300bhp from their race-prepped hemi-headed Chrysler V8 motors. Cunningham was not there to make up the numbers, but to provide the biggest cross-pond challenge to the European racing aristocracy since Brisson and Bloch’s Stutz Blackhawk came achingly close to upsetting the Bentley applecart in 1928.

The north? Well, that would be the Brits. Three works Aston Martin DB3s arrived, a year late perhaps but keen to show what they could do. But really all eyes were on the Jaguars. They’d won the year before with the brand new C-type and now there were three of them, sporting new low-drag bodywork that made up in purpose and presence whatever they had lost in pulchritude.

This Jowett Jupiter R1 driven by Marcel Becquart and Gordon Wilkins was one of just 17 cars still running by the end of the event.

Getty Images

And then there were the Germans from the east. Three gleaming W194 ‘300 SL’ coupés, their gullwing doors being the most elegant way imaginable of meeting door aperture regulations with the high, wide sills required to bequeath sufficient structural strength to its spidery tubular frame. It was these cars that were the reason for the Jaguars so dramatically changing their appearance, and we’ll be getting to that shortly too.

But not before looking at those from France itself. It seemed there wasn’t much: there was the Gordini of course, with Jean Behra driving, but its 2.3-litre engine was surely too small and stressed to last 24 hours of the kind of punishment only Behra could dish out. And there was a smattering of Talbot-Lago T26GSs, good cars in their day, good enough indeed to win this race outright back in 1950, but elderly now and driven by privateer entrants seemingly unequipped to deal with the works teams with more modern metal that were expected to dominate.

“The heavy Astons with their 2.6-litre engines just didn’t seem quite up to the job”

But who would it be? If firepower were the sole determinant, it would probably be one of the Ferraris, but having won the race in 1949 they’d since proven fragile: a total of 14 had entered in the intervening two years, of which just four made it to the end. So perhaps the thundering Cunninghams might be there to pick up the pieces? Not so fast over a lap, they had staying power, at least in theory.

There was more hope than genuine optimism for the French contenders and understandably so, and the heavy Astons with their 2.6-litre Lagonda engines just didn’t seem quite up to the job. So it looked like being a fight between the Mercedes and the Jaguars, and it was one the defending champion had no intention of losing.

But Jaguar had feared it might. With its total domination of pre-war grand prix racing, no one doubted that Mercedes-Benz still had the will to win as well as the talent. Alfred Neubauer and his gifted chief engineer Rudi Uhlenhaut were itching to go racing again while its star driver when hostilities had stopped racing, Hermann Lang, was still hardly over the hill at the age of just 43. What it appeared to lack was the way. Mercedes-Benz was a very different company after being on the losing side of a six-year global conflict. It didn’t have the money to go racing the way it always had in the past, or would choose to now. It couldn’t countenance a return to grand prix racing and even a sports car programme would have to use a lot of proprietary parts, including the entire powertrain.

And that was an enormous problem. All that existed was the 3-litre straight six from the 300 saloon with its four-speed gearbox, neither of which had been designed with the slightest thought for competition. And try as Uhlenhaut’s team might, no more than 180bhp could be extracted from it, at least 100bhp less than that under the right foot of a Ferrari 340 America driver. And it would need to be detuned slightly to survive 24 hours of racing.

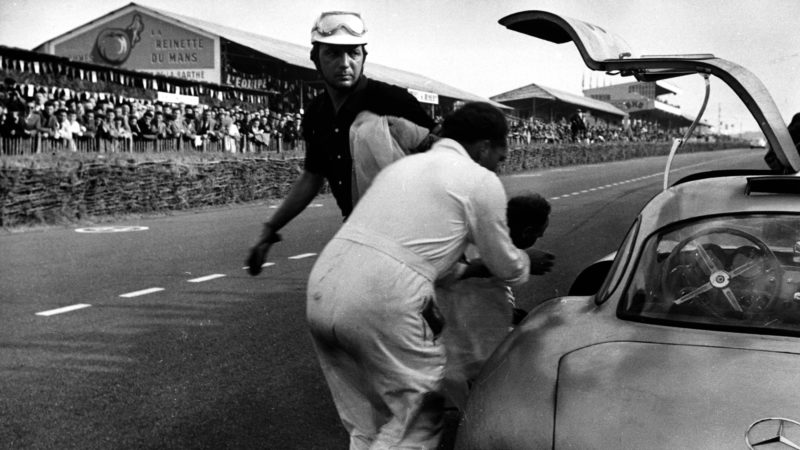

the Germans arrived at Le Mans meaning business with five competition cars (two spares) and around 40 mechanics, one of whom is stepping around driver Theo Helfrich

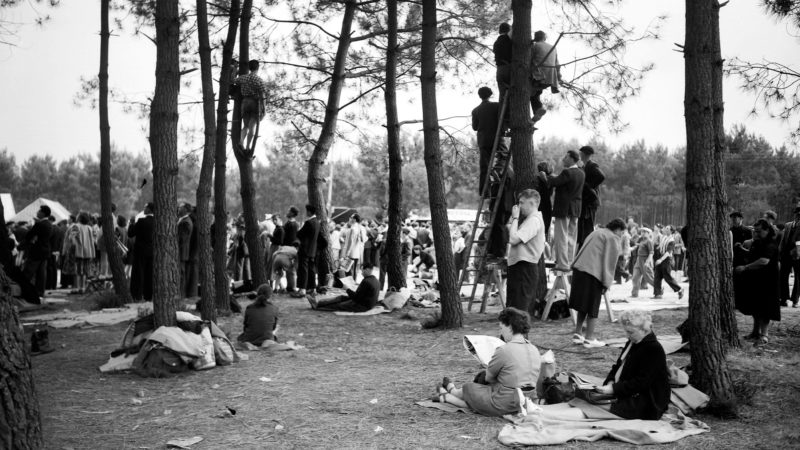

Tree-climbing spectating from an era that largely eschewed health and safety

A check of the Nash-Healey – Britain’s best performer in 1952, earning third spot

Mercedes-Benz couldn’t outpower the opposition, so it decided to outsmart them, making a car that in terms of its lightness, aero efficiency and standard of preparation would be second to none. The 300 SL was the result.

The 300 SL made its debut at the aforementioned 1952 Mille Miglia. There were no works Aston DB3s there, and just one factory C-type, the hard-worked third prototype that had won Le Mans the year before. And it was only there with the grudging agreement of Lofty England to allow Stirling Moss and Norman Dewis to prove the concept of the disc brake in Europe’s toughest road race. In time, England would come to wish he had never said yes.

For while the C-type’s ‘plate brakes’ would perform flawlessly and sow the seeds for Jaguar’s dominant victory at Le Mans the following year, in the more immediate term it was that car’s participation in the Mille Miglia that just as surely doomed the team’s effort at Le Mans six weeks later.

For it was the sheer speed of the W194s that scared Stirling into action. “There was this section near Ravenna,” he once told me. “I was going as fast as I could, probably 150mph, and one of these things just came flying past. I didn’t think anyone could be going faster than me.” In print its driver is usually said to be Karl Kling though he told me it was Rudi Caracciola, but in any event it wasn’t the pilot’s identity but the speed of his car that was at issue. Fatefully, it led Stirling to send an unambiguous telegram to William Lyons. It simply read “must have more speed at Le Mans”.

It was too late to fit disc brakes and besides Lofty was worried about boiling brake fluid. Nor was there time to find more power. So the already commendably aerodynamically efficient car would have to be made more slippery still. The job was, of course, entrusted to Malcolm Sayer who had no choice but to rush it and came up with a strange droop-snoot nose with a smaller air intake and elongated tail. Crucially the new bonnet line meant the radiator could not be mounted upright, so was slanted and fed by a header tank mounted on the bulkhead. In charge of this engineering redesign was, given what was later to transpire, the unfortunately named Roy Kettle.

Given the worrying time constraints involved, the test programme for the modifications was somewhere between derisory and non-existent. They were driven to Le Mans as usual and seemed fine on the way down, but compared to the heat of battle, flat out at average lap speeds well in excess of 100mph, that was no comfort at all. In fact it was meaningless.

The American Cunninghams made a solid start but No8, Levegh, would surge into a huge lead

Getty Images

The team knew it was in trouble from the first practice session. The new bodywork produced some instability when driven flat out, but that was containable. It also deprived the drum brakes of cooling air, but that could be managed. What could not was the fact that all the cars overheated the moment they were driven at race pace.

Salvation seemed to come from the presence in the paddock of both the Mille Miglia C-type and the first privateer car, owned by Duncan Hamilton. They were both relieved of their old-style radiators with their integral header tanks and two of the three C-types were duly attacked with hammers to modify the bonnets to accommodate them. For the third, the inevitable early bath awaited.

It would not take long. The race started at 4pm on Saturday afternoon, Ascari bolting away from the running start in Ferrari’s Mille Miglia winner, completing a 4min 40.5sec lap in his first stint – an average of over 108mph – which would stand until he smashed it again the following year. Fast though the three Mercedes were, they weren’t that fast. Indeed, in those early hours, they languished in ninth, 10th and 11th places. But three hours in Ascari’s clutch failed, starting a domino topple among the Ferraris. Of the seven entered, just one would see the flag, the 340 America entered by double Le Mans winner Luigi Chinetti and driven by André Simon and Lucien Vincent. Having led early on it fell back and finally recovered to finish fifth.

No6 is the Talbot-Lago T26GS of André Chambas and André Morel – the same model as Pierre Levegh’s, who led in the race. Nos 1 and 2 are the 5.4-litre V8 Cunningham C-4Rs – the open-top one would end up fourth

Alamy

Mind you, that was one more than Jaguar managed. The first C-type to go barely made it past the first hour, the unmodified car of Ian Stewart and previous winner Peter Whitehead succumbing to quite inevitable head gasket failure little more than an hour into the race. Stirling’s engine blew after three hours while the last surviving car of Hamilton and Tony Rolt made it to early evening before it too overheated and died. With barely one sixth of the race run, Jaguar had turned the triumph of the year before into ignominious failure.

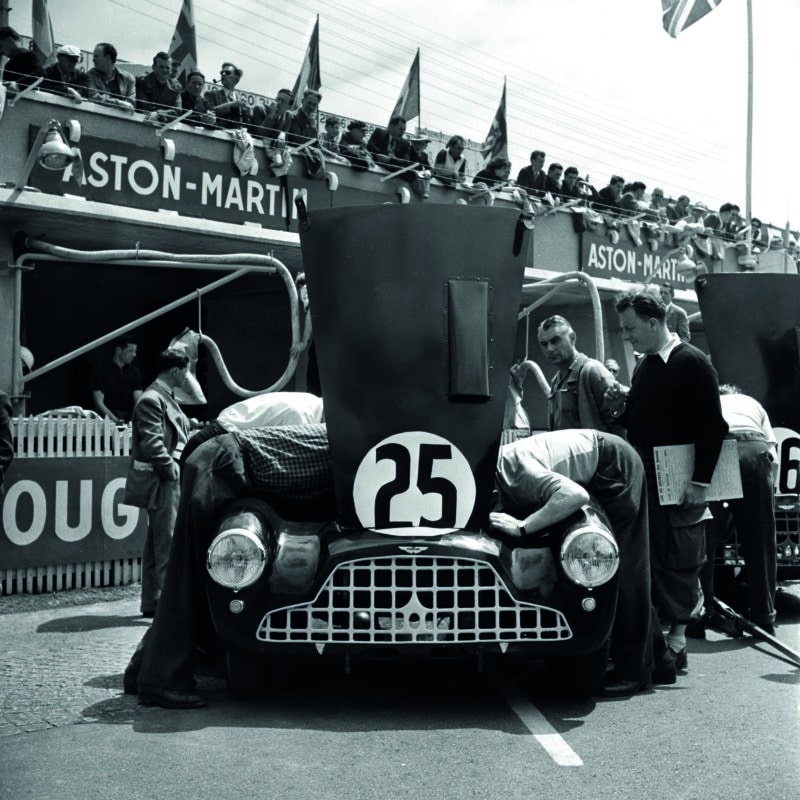

The Astons fared better, but not by much. Official records show the three DB3s turned up to race the works Ferraris, Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar teams with engines developing just 138bhp. Underpowered and overweight, they started being felled by rear axle failure early in the race, though the last survivor, driven by the super talent that was Peter Collins and Lance Macklin made it to the 22nd hour and in third place too, thanks to the extraordinary rate of attrition.

Trouble for the Jaguar of Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton

Getty Images

Of the 57 cars that lined up in front of 400,000 spectators on Saturday afternoon, just 17 would still be running a day later. A Mercedes-Benz walkover then? That’s certainly what appears to have happened. Look at the records and they will show that Lang and his co-driver Fritz Riess won, with the sister car of Theo Helfrich and Helmut Niedermayr a lap down in second place. Third went to the Anglo-American Nash-Healey of Leslie Johnson and Tommy Wisdom, but they were 15 laps – some 125 miles on the circuit in that year’s format – off the lead. And the Cunninghams? Two out of three went out with engine failure, leaving the car of Briggs Cunningham and Bill Spear to trail home 10 laps behind even the Nash-Healey. Not so reliable after all.

The truth is nothing like that. Indeed a Mercedes only led the race for the first time after nearly 23 of its 24 hours had elapsed.

For it turned out the gullwing 300 SLs weren’t that fast after all, as their modest power output always suggested. It left Lofty England kicking himself: “Although they won, the allegedly fast Mercedes had proven to be slow, to the extent that if Jaguar had run its 1951 cars with only larger carburettors and self-adjusting rear brakes, they might well have finished first, second and third!”

So why had one gone belting past the Boy Wonder on the Mille Miglia? There are two plausible explanations, the truth probably lying in a combination of both. First, the weather was filthy and the Mercedes drivers were able to sit bone dry behind big screens with wipers. More telling was that Mercedes had been in Italy for weeks, all its drivers having completed multiple laps of the course before the race. Simply put, they not only could see where they were going, they knew where they were going, too.

It was a poor showing by the Aston Martin works team, which raced with the DB3. None lasted the distance

Getty Images

Back at Le Mans, the challenge to the might of the Mercedes-Benz team came from two sources, each as unlikely as the other and for entirely different reasons.

The first came from that Gordini. Everyone respected Amédée Gordini’s engineering skills, sufficient for him famously to be nicknamed ‘The Sorcerer’, but few expected his little T15S either to be that fast or to last. Underneath this was a 1951 chassis derived from a 1947 grand prix car over which the requisite enveloping bodywork had been draped, and its 2.3-litre engine was a stretched and highly strung Formula 2 unit.

But fast it was, thanks in no small part to the tigerish Behra and his team-mate and also current grand prix driver, the rather underrated Robert Manzon. So when the Jaguars and Ferraris started to fail, it was not a sleek silver German coupé that swept into the lead as day turned to night, but a little blue French roadster. And it held it.

But at this still relatively early stage, Neubauer would not have been too troubled. He would have remembered how Bentley had won this race in 1929 driving as slowly as possible, and how concealing that pace had allowed the British team to run his Caracciola-helmed SSK Mercedes into the ground to win again the following year. Besides, he had already lost one of his cars, Kling’s going out with alternator failure.

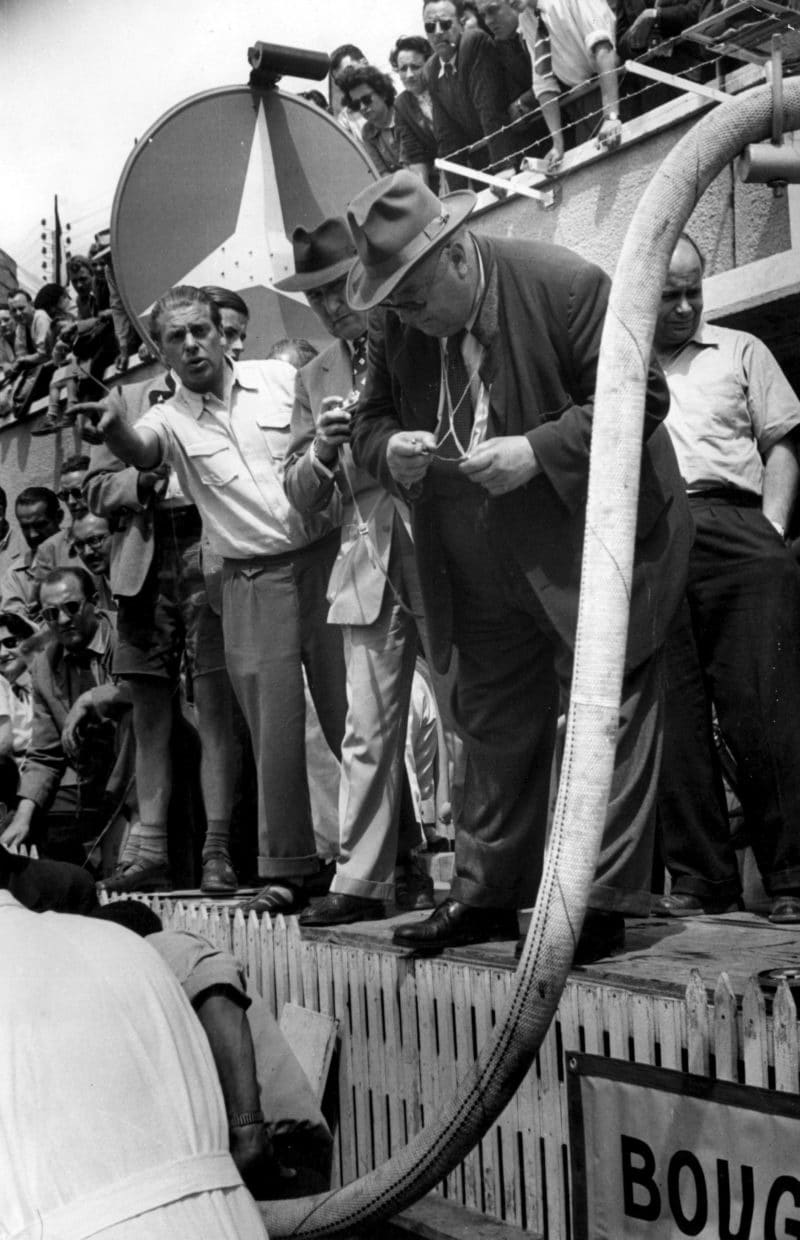

Mercedes-Benz racing manager Alfred Neubauer times his mechanics in the pit

Getty Images

With Manzon now at the wheel, on the Gordini hurtled at what this magazine reported as “terrifying speed”. Could it possibly last? It could not. At 3.30am it came in, with trouble not in its engine but its front brakes. Its intrepid drivers were all for carrying on with rear brakes alone, but The Sorcerer said no, and that was that.

Yet long after any threat from Ferrari, Aston Martin, Jaguar, Cunningham and Gordini had been neutralised or removed, still the Mercedes did not lead.

So it is finally time to meet the true hero of our story, a man called Pierre Bouillin whom you may not think you’ve heard of. But you have. In need of a name with which to go racing, he had re-arranged the letters in his uncle Alfred’s surname, turning ‘Velghe’ into ‘Levegh’. Pierre Levegh: the man who was driving a Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR at Le Mans three years later when it launched off the back of Lance Macklin’s Austin Healey 100S and into the crowd, triggering the worst accident in racing history.

For now, however, he was a man on a mission. In his privately owned, self-prepared Talbot-Lago L26GS, and at the age of 47, Pierre Levegh now led Le Mans. And he had got there on his own, as he had so far not allowed his perfectly capable team-mate René Marchand to take the wheel. His car was an ageing design, but strong, gutsy and made more powerful by his own modifications to its 4.5-litre straight six engine. And he was driving flawlessly.

Incredibly, it seems that Levegh attempted to go all the way, driving the full distance without a break

Getty Images

By 9am and with just seven hours to run, Levegh had a four-lap lead over the chasing Mercedes pair, the thick end of 20 minutes, and still he drove alone. He could have stopped, had the car thoroughly serviced and allowed his team-mate to do just one stint while he got some rest and things might have turned out very differently. I don’t think Levegh started the race intending to go it alone, but as the hours counted down, my guess is that the chance to write an indelible line of history for himself became irresistible. So onward he charged.

And while the Gullwings did speed up towards the end of the race, I have read nothing that suggests there was any chance of catching the Talbot unless it hit trouble. This title wrote that with two hours to go “Mercedes-Benz was obviously content with second and third places”. Behind the wheel of the Talbot, Levegh appeared on autopilot, clearly well within the realm of clinical exhaustion. He had been sick in the cockpit, too. Yet so well did he know this place, he still lapped faster than had the winning C-type at the same stage the year before, and still held a comfortable two-lap lead over the Mercedes.

The dream turned to dust just before the start of the final hour. Some say the crankshaft snapped, others that a big end broke up. Some said it was Levegh’s fault as, near comatose, he missed a gear, others that Levegh was the only reason it had survived so long, he having detected a vibration in the motor before the race and concluded that only he would have the mechanical sympathy to manage it, hence his heroic but ultimately futile solo effort.

When Levegh’s Talbot-Lago croaked, the following Mercedes took 20 minutes to get ahead on distance

Magic Car Pics/Shutterstock

Only now and for the first time since the start of the race did the two surviving Mercedes ease into the lead they would maintain to the flag. Was it a lucky win or one achieved through masterly tactics?

The answer is both. Two-thirds of Neubauer’s team survived, which is more than can be said for any of the other alleged front-running factory squads and clearly its standard of preparation was of a different order to any of its rivals. But the cars were never that quick and it is simply not the case that they just held back, ready to pounce whenever the time was right, because had that been true they’d have been on poor old Levegh in a heartbeat. In fact they never got near him, and when his Talbot broke didn’t so much take the lead as inherit it.

Still, no one wins Le Mans without a bit of luck and you go a long way to making your own luck by being around to capitalise on the misfortune of others, should it occur. And at Le Mans in 1952 bad luck stalked the length of the pitlane.

Winning driver Riess, Mercedes team boss Neubauer and Riess’s co-driver Lang

Almost. For there is an unsung hero, the last of an impressively long cast of characters to have popped up in this story. If you think Mercedes did a good job in a race of such attrition that over two-thirds of the field retired, consider the achievement of Scuderia Lancia. It entered two B20 Aurelias, lightly modified road cars powered by 2-litre four-cylinder engines. Both produced near flawless races, coming home in sixth and eighth overall, even the slower of the two some 21 laps ahead of the next-best car in the class. With all the drama up front it may not have hit the headlines, but after Levegh’s doomed bid for glory, it was probably the most impressive achievement at Le Mans that weekend.