How Williams has become the force behind electric racing

The F1 team is languishing on the grid, but, as Damien Smith reports, its Advanced Engineering offshoot is the force behind electric racing – and will power the new LMDh endurance class

There’s something binary about Williams in the modern world. In the unflinching glare of the Formula 1 spotlight, the race team is reduced to a sadly emaciated ‘big beast’ of the grid, a once-great entity now running around as a backmarker. But widen the circle of light and another Williams emerges – one that not only represents the best of what 21st century motor sport has to offer, but also considered among the greatest rising success stories of the past decade. As Williams Advanced Engineering, the company that Frank Williams and Patrick Head built from scratch in 1977 is in the best form of its life.

Name an innovative new motor sport series, class or category and more often than not the words ‘Williams’, ‘Advanced’ and ‘Engineering’ will pop up in the press release, presentation or news story. The company is seemingly everywhere, thanks to its burgeoning reputation as the go-to specialist in electrification, hybridisation and lightweight engineering. It’s not just sparking in the world of cars and racing either. Visit the company’s website and you’ll find a barrage of projects, from electric mining trucks to collaborations with BAE on battery development to make fast jets more efficient, and even an investment into eco-friendly valve technology for aerosol cans. Thriving barely covers it.

But naturally it’s the motor sport projects that catch our eye: WAE will supply the standardised batteries for the new LMDh endurance sports car class that everyone is talking about; it’s energising not only the Extreme E electric off-road series, but also the next-generation Formula E car for the gamechanging Gen3 era; and it’s also providing the charge for the future of touring car racing, in the form of Pure ETCR. A good time to catch up with the company, then, and discover more about what might well end up being Frank and Patrick’s most significant and influential legacy.

The Williams Advanced Engineering facility is a stone’s throw from the F1 set-up

First, let’s clear up who owns it. WAE was founded in 2010, primarily out of Williams’ investment in the original F1 KERS technology when grand prix racing first embraced energy recovery systems. In December 2019, private equity company EMK bought a controlling interest with Williams Grand Prix Engineering maintaining a “significant minority stake” – and when Dorilton Capital bought up the F1 team last autumn, that share in WAE was part of the deal. So the company that started off as an F1 offshoot now exists in its own right, employing around 350 people, but retains a vital physical, practical and spiritual connection to the grand prix team for which Williams is best known. “We operate very much linked to them,” explains WAE technical director Paul McNamara. “Our position on the Grove site next to them is key to our proposition to the world.”

That premier-grade reputation – apparently impervious to Williams’ current F1 malaise – has contributed to WAE’s emergence as a global leader in motor sport innovation. Doug Campling, chief engineer of WAE’s motor sport division, offers some insight into the new projects that are leading its charge.

LMDh: Catching the zeitgeist

Audi’s LMDh concept teaser

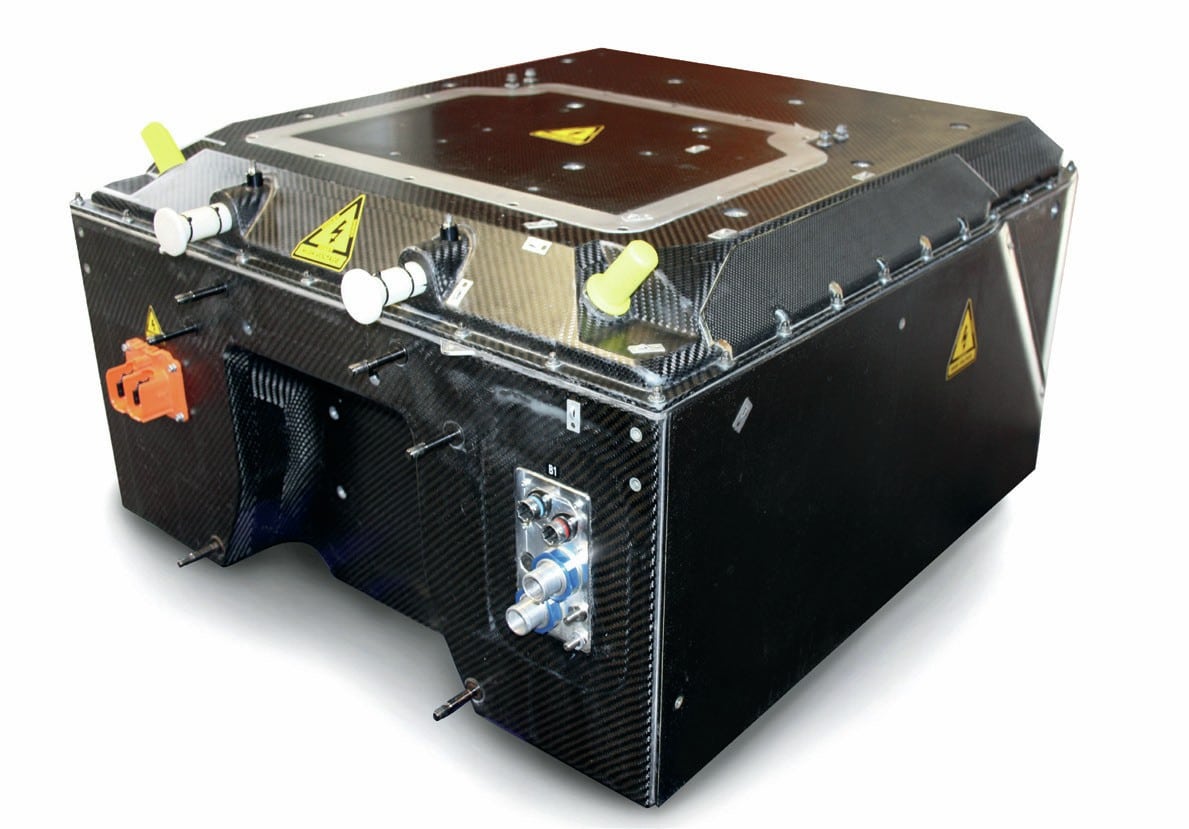

Le Mans Daytona hybrid: the future is all in the name of endurance sports car racing’s new class that promises to unite the European-based World Endurance Championship and IMSA in the US under one rulebook, and run in parallel on equal terms with the Hypercar category that takes its bow this year. LMDh will go live next year and features plenty of standardisation to cap expenditure, including a spec hybrid system producing 50kW (67bhp) for a combined maximum output of 500kW (671bhp). WAE, which previously made the flywheel energy storage system used by Audi in LMP1, is responsible for the battery, DC-DC converter and the bespoke battery management unit, mated to Bosch’s hybrid motor and an Xtrac gearbox. Audi, Porsche and Acura are already committed to LMDh for 2023, and with the promise of customer cars to boost grids for what could be a new golden era of sports car racing, Campling and his team can expect plenty of demand for this one.

WAE’s LMDh battery

“The company that started off as an F1 offshoot now exists in its own right”

“Parity with Hypercar, to ensure LMDh has a fair crack at an overall win at Le Mans and anywhere else where Hypercars might compete, is central,” says Campling. “The technical challenge is that it’s a true high-power density, lightweight hybrid application, and is analogous to F1 KERS in the early days and now ERS, rather than the electrification model of an energy-dense solution.”

We might not see LMDh out on track for a while yet, but Campling reports good progress on development. “The hybrid team, ourselves, Bosch and Xtrac, have been working together very well now for over a year,” he says. “Motor sport is a small business and we knew each other anyway. We’ve been introduced to the four chassis constructors [Dallara, ORECA, Ligier and Multimatic] more recently, and so far so good. Everyone knows we are trying to start something here and everyone sees the huge opportunity, so at the moment everyone is playing nicely!”

Artificial balance of performance is unavoidable to allow LMDh, which features power fed to the rear axle only in contrast to both on the Hypercars, to be viably competitive. Campling is bullish that BoP will work, as it has in other categories. “The duty cycle with the hybrid system has developed in recent months to ensure there is a baseline performance parity between the two classes,” he says. “BoP is something that both IMSA and [Le Mans organiser] the ACO primarily have done a good job on in sports car racing. Le Mans is a sprint race now and the lead cars are often on the same lap after 24 hours, and that’s a real success story for BoP. Clearly the people who are paying the most money to develop the car find BoP frustrating because it really does challenge how you spend your money on development. You have to be clever, especially on aerodynamics, to be competitive across the widest operating window: dry, wet, day, night. I’m pretty confident the job that will be done around the BoP is not any cause for concern.”

Formula E Gen3: EV game-changer

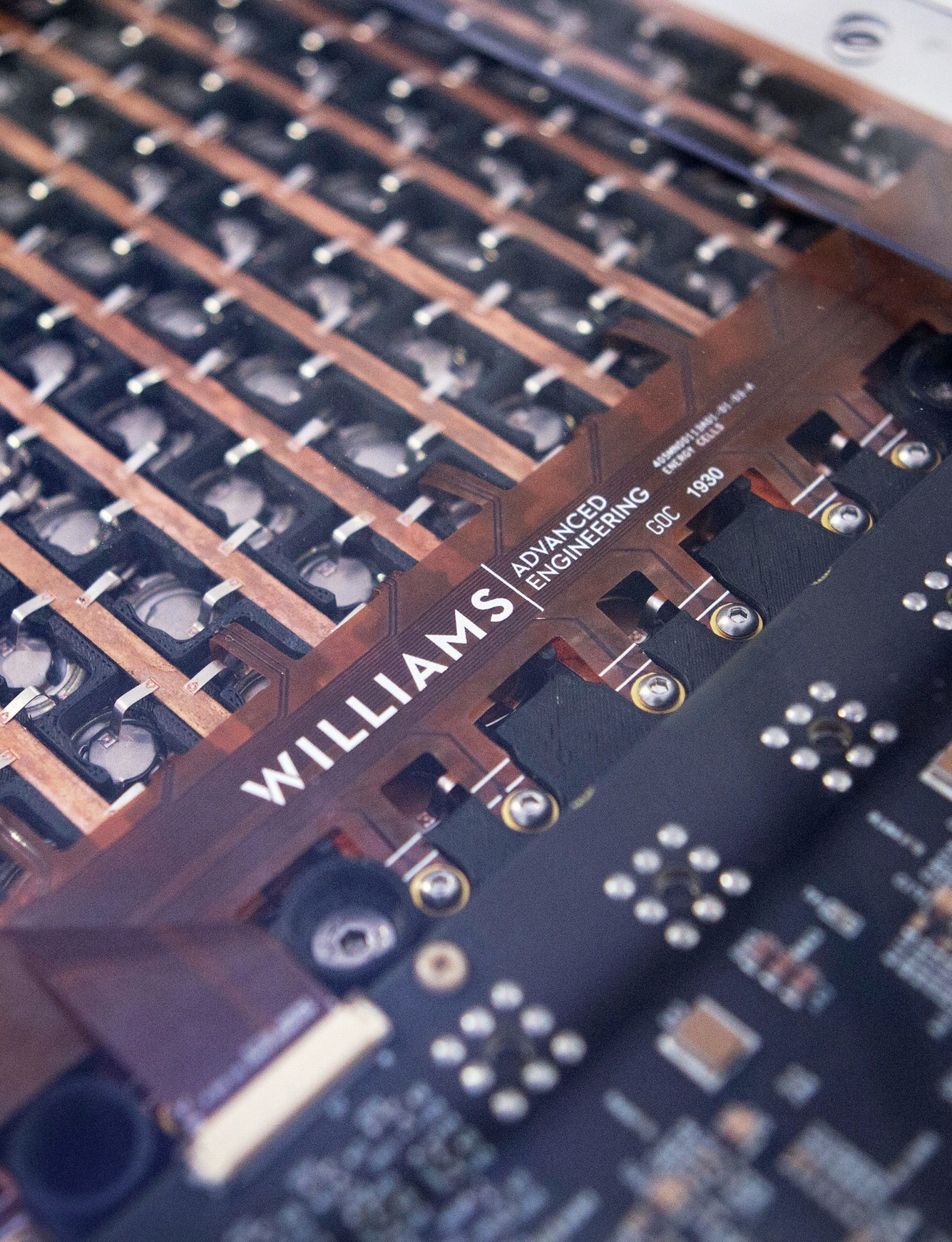

Was there some satisfaction when WAE won the business to supply the battery for the Gen3 version of Formula E, we ask Campling innocently? “Absolutely,” he fires back with a big grin. While WAE was the supplier for the first generation of Formula E car back in 2014 and has remained involved in the series via its collaboration with Jaguar, McLaren Applied provided the power source for Gen2 – hence Campling’s obvious delight.

The Gen2 Formula E line up in 2019

Gen3 promises to significantly raise the stakes for Formula E from next year thanks largely to a reported figure of 350kW (around 470bhp) of peak power in qualifying – 100kW up on Gen2. It’s billed as a game-changer for the perception of EV propulsion in motor racing and represents a proper approach to a bespoke EV race car. It has front-axle power regeneration as well as rear for an impressive total of 600kW and fast-charge pitstops. The series hopes that the changes mean the new car can’t be confused any longer with a battery powered Formula 3 car and ensure Formula E is in the vanguard of that development for the future. Campling is reticent about the details: WAE has been sworn to secrecy ahead of Gen 3 appearing in 2022/23.

Extreme E: Off-grid sensation

Scepticism about the environmentally focused ethos behind Extreme E is all too easy, but the more we discover about Alejandro Agag’s allelectric off-road concept, the more exciting it looks. Addressing gender equality in the driver line-ups and striving to inform and educate its audience on climate change are laudable ambitions, but it’s the potent performance of the 400kW (550bhp) buggies that will get the heart racing – although at the first round in Saudia Arabia power was cut to 225kW, in part because of high battery temperatures..

As in Formula E, WAE linked up with chassis builder Spark to provide the battery for a short format of off-road racing that has more in common with rallycross than rally raid. A desert event started the series, with rainforest, glacier, arctic and coastal to come.

Extreme E’s 400kW buggy might even appeal to those psychologically wedded to the internal combustion engine.

“As ever with all race batteries, weight was a key constraint,” says Campling. “But for Extreme E it was about robustness and simplicity, and that went into all sorts of decisions. The ability to maintain the battery in extreme environments fed right the way through the mechanical design and into concepts around cooling, conditioning, vehicle installation and maintenance of the pack.

“Extreme E is spectacular. From the manufacturers’ point of view, the fact it is an SUV leans towards the market they are keen to promote. It’s exciting in the places it is going, the story it is telling, the team owners and drivers involved” – Hungarian Grand Prix to go. It was Kovalainen’s only Formula 1 victory. Team-mate Lewis Hamilton, Nico Rosberg and Jenson Button – “and the gender balance in the series is another story. Alejandro has caught the crest of a wave once again.”

“eSkootr racing promises to be spectacular and terrifying in equal measure”

Pure ETCR: The tin-top future

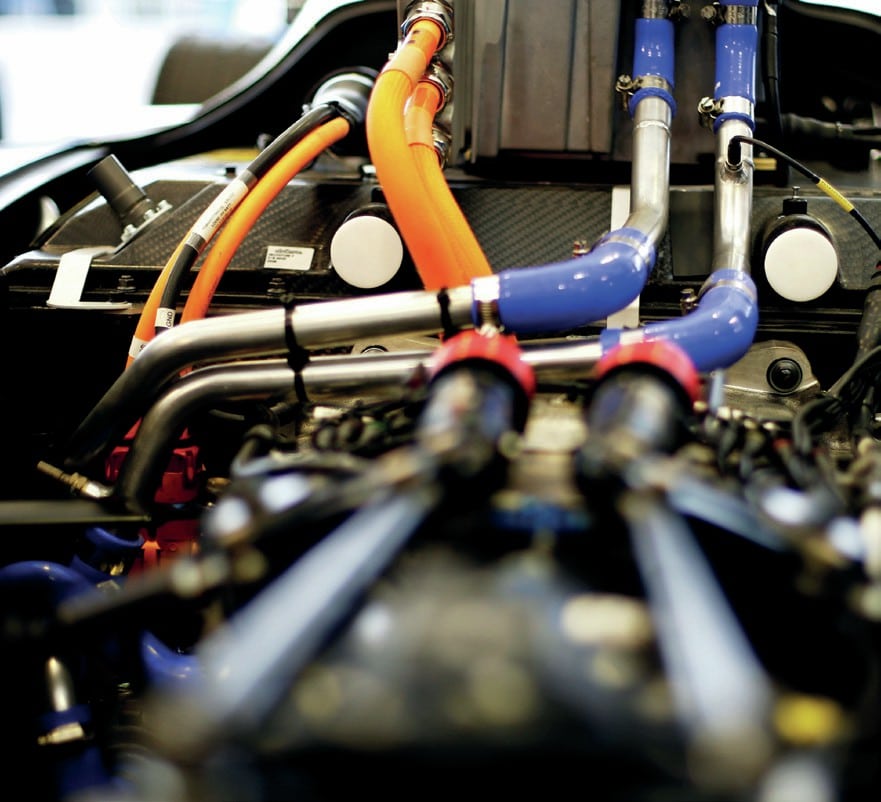

That billing is no exaggeration. Created by Marcello Lotti, the force behind TCR, the first electric touring car series is set to spark up this year – even if range constraints again limit Pure ETCR to a rallycross-style short racing format. But there’s nothing short about the performance of these cars, with Hyundai, Cupra and Alfa Romeo (a customer team) committed. The WAE 798V battery pack offers peak power of 500kW (670bhp) and 300kW (more than 400bhp) of continuous power with a 62kWh capacity and can be recharged in less than an hour from 10% to 90% at 60kWh. A fiveround series is due to kick off at Vallelunga on June 18-20.

“This really had to be cost-effective,” says Campling. “The whole essence of TCR has been incredibly successful, there are over 400 of them worldwide and that’s based around affordability and accessibility. So cost was the biggest driver in terms of cell selection.

“The scope for this is huge. Marcello has had approaches from all the regional series that TCR runs in and it gives the manufacturers something that is road representative.”

eSkootr: Youthful exuberance

It falls outside of Campling’s remit, but we can’t sign off without mentioning the electric scooter series WAE has also taken on. As the eSkootr Championship suggests, this one is aimed at the ‘yoof’ market and looks set to capitalise on a form of racing that has already gained traction for the X Games generation. WAE is building the chassis, battery and powertrain for this one, for a project that involves Formula E racer Lucas di Grassi and ex-Williams F1 driver Alexander Wurz. Reaching speeds of 60mph, urban eSkootr racing promises to be spectacular and terrifying in equal measure.

So Campling and his team have a lot on their plate. Is there capacity for more? “Always!” he laughs. There’s an acceleration of innovation in motor sport right now, and it’s great to see Williams in the middle of it – just as Patrick Head was during the great days of his F1 team. But scepticism, cynicism and hostility linger over electrification for too many enthusiasts. You might be one of them. So what is Campling’s message to the doubters, to convince them to open their minds? “Sit in an EV race car off the line,” he says. “It’ll do an eighth of a mile quicker than anything with an ICE. Motor sport is a broad church. EV has earnt its place – and it’s only going to grow.”

Where we go next…

As car-buying trends shift towards electric, public scepticism towards e-sport might begin to thaw

It’s notable that Williams Advanced Engineering technical director Paul McNamara credits F1 for his company’s emergence as an electrification pioneer, given the reticence of grand prix racing to fully commit to battery or fuel cell propulsion. “We’re fortunate to be involved in something that is a societal mission to decarbonise,” he says. “We’re in the right place at the right time. In terms of motor sport, WAE owes itself to the vision of F1 back when they first set up KERS, which forced Williams and others to invest in a lot of capacities on batteries, controllers and motors. It forced us to invest in facilities and engineers to do that, which then moved across to this more electric form of motor sport. Without F1 that serendipity wouldn’t have happened.”

The low energy density of batteries makes full electrification a non-starter for F1, before one even considers that Formula E already exists, not to mention the seismic philosophical and cultural shift that would be required for such a revolution to be accepted. But as governments and the wider automotive industry plough on towards the apparent nirvana of a fully electric future for our road networks, just how much progress is there still to be found in battery fuel cell technology?

“The key challenge for electrification is the storage for a given mass ratio,” says McNamara. “How are we going to improve that? People talk about a limit that’s coming, probably 20-25% away from where we are now. But there’s other technologies: semi-solid state, solid-state and lithium sulfur that will probably keep that progression going. On a typically good battery pack, maybe 70% is the chemistry, 30% is the other stuff which conventional engineers can nibble away at. But from where we are now, making a 25%, 30% or even 50% improvement on range is a lot.”

He points out that fast-charging, a key selling point of Formula E’s future, is another area of focus for WAE. “The practicality of electrification is not just how much you can store, but how much you can get in quickly,” says McNamara. “Infrastructure, fast charge and how much we can store for a given weight will feed a virtuous situation where we can electrify most of our on-ground propulsion needs.”

What about the alternatives, such as hydrogen, a form of energy that will gain its own class at Le Mans from 2024? “Hydrogen has a place,” he acknowledges. “There are certain needs for range extension and hydrogen fuel cells are probably right for that, for example in aircraft. But the good thing about electrification is there’s plenty of infrastructure. Every house and street has electricity, we have an established power infrastructure. You talk to generating people and they say they don’t have a problem generating the stuff, and it’s getting greener all the time. You think back 20 years, we used to worry about heating our houses electrically because we thought it an inefficient way of doing so. Now that has shifted 100%. So I think electrification is the way rather than changing our gas networks to be full of hydrogen. That’s just too hard.”

Fill her up: a key challenge to electric is quickening the charge-up time

At the same time, McNamara acknowledges and understands the scepticism of full electrification in F1 circles, where synthetic and biofuels are preferred as the best route toward zero emissions – and won’t require an uprooting of grand prix racing’s fundamental essence.

“All this co-exists for the foreseeable future,” he says. “It doesn’t make sense for F1 to semi-imitate Formula E. They have to evolve on a parallel path. It has tacked on hybridisation to the internal combustion engine and will follow that journey. There will come some point none of us can predict, likely measurable in decades, when that evolution will take them to something very different – but it is an evolution.

“Then in parallel to that you’ve got something different with Formula E and now Extreme E, Pure ETCR and so on. They have to go through their own evolution to build their fanbase and bring people with them. That will run in tandem with what is happening in the real world, with people buying more electric cars.”